65 min read

·

Processual Becomings

Chapter One detailed the three syntheses of the unconscious, a history of schizophrenia and capitalism’s role in producing the schizo, while also introducing Deleuze and Guattari’s broader metaphysics. Chapter Two begins with the myth of Oedipus and its relation to psychoanalysis.

Note 1: I will constantly be revising this blog post in order to do a line-by-line interpretation of the text.

Note 2: To understand Lacan’s structuralism — which this section focuses on — it might be useful to review Deleuze’s essay What is Structuralism?. My blog post on this can be found here.

Note 3: To understand the complexity of Deleuze and Guattari’s analysis of Lacan’s Symbolic, it might be useful to review Lacan’s Seminar on the Purloined Letter. My blog post on this can be found here.

- Citation Note: Full citation provided at the end of this post

Paragraph One

Deleuze and Guattari begin the second chapter by saying:

Oedipus restrained is the figure of the daddy-mommy-me triangle, the familial constellation in person. (AO, 51)

The “familial constellation” refers to the triangular structure of the nuclear family through which psychoanalysis interprets desire. In this way, Oedipus is the personification of the daddy-mommy-me triangle. They write:

But when psychoanalysis makes of Oedipus its dogma, it is not unaware of the existence of relations said to be pre-oedipal in the child, exo-oedipal in the psychotic, para-oedipal in others. (AO, 51)

Oedipus functions as the dogma of psychoanalysis as everything must ultimately refer back to Oedipus in some way, shape, or form. In Chapter 1.6, Deleuze and Guattari’s reading of Melanie Klein illustrates how even so-called “pre-oedipal” stages are already oedipalized, as they presuppose the Oedipal structure from the outset. The “exo-oedipal in the psychotic” isolates how forms of psychosis that seem to depart from the normative Oedipal triangle are still defined and understood in relation to Oedipus. Lastly, the “para-oedipal” relations observed in various syndromes or other peoples remain parallel to Oedipus. Everything — including pre-, exo- and para-oedipal states — are always already oedipalized.

Deleuze and Guattari write:

The function of Oedipus as dogma, or as the “nuclear complex,” is inseparable from a forcing by which the psychoanalyst as theoretician elevates himself to the conception of a generalized Oedipus. (AO, 51)

For the psychoanalyst, Oedipus is not merely one possible structure of desire — it is the only one. When Deleuze and Guattari speak of “forcing,” they emphasize that Oedipus is not uncovered through analysis but rather imposed onto it. Oedipus is a totalizing framework that grants the psychoanalyst an authoritative position, allowing them to interpret all desire through the lens of a “generalized Oedipus.”

Deleuze and Guattari continue by outlining two approaches for the psychoanalyst. One approach is focused ont the individual and one is focused on the group:

On the one hand, for each subject of either sex, [the psychoanalyst] takes into consideration an intensive series of instincts, affects, and relations that link the normal and positive form of the complex to its inverse or negative form: a standard model Oedipus, such as Freud presents in The Ego and the Id, which makes it possible to connect the pre-Oedipal phases with the negative complex when this seems called for. (AO, 51)

- In the original French text, “Oedipal” is not capitalized in the term “pre-Oedipal” above.

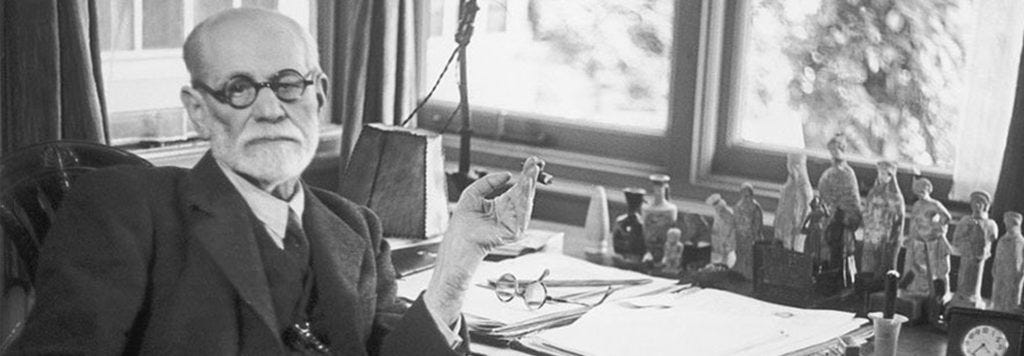

Regardless of the subject’s sex — understood here through the classical male/female binary — the psychoanalyst interprets the subject’s instincts, emotions, and relationships through the lens of Oedipus. The patient’s “intensive series” of experiences is rooted in the Oedipal model. This model comes in two forms: a “normal and positive” form, where the subject expresses desire for the parent of the opposite sex and rivalry with the same-sex parent; and a “negative” form where these dynamics are reversed. Despite the differences in these forms, both forms are treated as variations of the Oedipal model. As Sigmund Freud isolates in The Ego and the Id (1923), even the early formations of desire — the so-called ‘pre-oedipal states’ — are interpreted as either not yet fully Oedipalized or as symptomatic of a failed progression towards Oedipus. Hence, why the “pre-Oedipal phases” are associated with the negative complex here.

Deleuze and Guattari continue:

On the other hand, [the psychoanalyst] takes into consideration the coexistence in extension of the subjects themselves and their multiple interactions: a group Oedipus that brings together relatives, descendants, and ascendants. (AO, 51–52)

The mommy-daddy-me triangle expands outward as it effectuates group formations. The phrase “coexistence in extension” refers to how psychoanalysis applies the Oedipal framework not just to an individual and their immediate parents, but to the broader network of family relations — siblings, aunts, uncles, grandparents, and beyond. Building upon this second point, Deleuze and Guattari write:

(It is in this manner that the schizophrenic’s visible resistance to oedipalization, the obvious absence of the Oedipal link, can be obscured in a grandparental constellation, either because an accumulation of three generations is deemed necessary in order to produce a psychotic, or because an even more direct mechanism of intervention by the grandparents in the psychosis is discovered, and Oedipuses of Oedipus are constituted, to the second power: neurosis, that’s father-mother, but grandma, that’s psychosis.) (AO, 52)

Psychoanalysis is both strategic and arbitrary in how it applies the Oedipal framework to any situation. Even in the case of the schizophrenic — where there is a “visible resistance to oedipalization” — the psychoanalyst extends the mommy-daddy-me triangle into wider familial constellations, such as the grandparents, and produces the schizophrenic as psychotic. To be clear, psychoanalysis does not argue that the schizophrenic and the psychotic are the same, but rather, finds schizophrenia to be an extreme form of psychosis. The point here is to isolate how psychoanalysis interprets the schizophrenic as psychotic via a familial constellation.

On one hand, the psychoanalyst might explain psychosis as the result of a multigenerational accumulation, where “three generations are deemed necessary” to produce a psychotic subject. On the other hand, the psychoanalyst might posit a direct cause to this psychotic subject, claiming that the grandparents themselves play an active role in psychosis. Thus, Oedipus is never discovered, but expanded.

To continue:

Finally, the distinction between the Imaginary* and the Symbolic* permits the emergence of an Oedipal structure as a system of positions and functions that do not conform to the variable figure of those who come to occupy them in a given social or pathological formation: a structural Oedipus (3 + 1) that does not conform to a triangle, but performs all the possible triangulations by distributing in a given domain desire, its object, and the law. (AO, 52; emphasis mine)

The translator’s leave a note:

*In capitalizing these terms, we have followed the suggestion of Jacques Lacan’s translator, Anthony Wilden…

(Translators’ Note.)

This section is extremely important and worth spending time on.

French psychoanalyst, Jacques Lacan, makes a distinction that Freud never did: the differentiation between the Imaginary and the Symbolic. The Imaginary pertains to the processes of identification and ego-formation — a domain characterized by images. The Imaginary is exemplified by the mirror stage, in which the infant, upon perceiving their reflection, identifies with the image as a unified subject. Then, the subject enters the Symbolic which is, by contrast, is concerned with language, law, and the social order. The subject is no longer unified but split, as they now identify themselves through a metonymic chain of signifiers.

Lacan marks a departure from the Freudian framework with this distinction between the Imaginary and the Symbolic. No longer is Oedipus reduced to the concrete figures of the mother and father. Instead, Oedipus is structured as a system composed of positions and functions that are not intrinsically tied to biological kinship or whatever occupies these positions. The question is no longer about the specific thing that occupies a place within this structure, but the fact that there are structural positions present within the structure. This structure is completely impersonal as positions are placeholders waiting to be occupied within the structure — again, it does not matter who or what occupies the position. Thus, rather than a fixed familial triangle of mommy-daddy-me, we encounter these Lacanian positions within the structure: “desire, its object, and the law.”

A few interpretations can be drawn from Lacan’s three points (we will get to the +1 soon); though they may not be accurate, they might be worthwhile to examine:

- To mirror Lacan’s three points to the Freudian triangle, it might be accurate to say that desire relates to the child (the one who desires), desire’s object relates to the mother (the desire to have sexual relations with the mother), and the law (the prohibition of sexual relations with the mother).

- In later chapters, we will encounter various paralogisms that describe the ways in which desire misuses itself in each of the syntheses. The identification of desire as a position for Lacan might be a nod to the third paralogism as this desiring-subject has a fully-formed ego (a desiring-subject). The identification of desire’s object might be a nod to the first paralogism as this would indicate a partial object lifted from the multiplicity (something that desire needs to obtain). The identification of law appears to be referencing the the second paralogism via the law of the father as an exclusive disjunction.

Regardless, the positions within the structure are fixed, meaning that while the specific figures that occupy these roles may vary, the roles exist independently of those who fill them. We have the three points down (desire, its object, and the law), but the +1 that Deleuze and Guattari reference is a bit vague as it could reference a lot of concepts. Thankfully, the +1 is clarified later in Chapter 2.5 and Chapter 3.4. Without going in-depth in later chapters, Deleuze and Guattari argue that the +1 is the pure signifier (also known as the master signifier or the phallus), serving as the transcendent term that distributes lack to all the elements in the structure.

In Chapter 1.5, Deleuze and Guattari utilize Lacan’s Seminar on The Purloined Letter to highlight Lacan’s view of the symbolic chain. Within this chain, a pure signifier (a signifier without a signified) enables signifiers within the chain to define themselves exclusively. To account for meaning changing over time, Lacan notes that elements within this chain are constantly shifting positions. Regardless of where the pure signifier is situated, it remains the organizing principle from which all other elements derive their meaning. This is the +1 in Deleuze and Guattari’s analysis; desire, its object, and the law, are all structured around this pure signifier, with this pure signifier distributing lack to all elements within the structure. No matter what occupies these roles, they are always defined through lack due to this transcendent term — this pure signifier. (Deleuze and Guattari’ criticism of this is that Lacan’s assumption that there is a single chain.)

Lacan’s reconceptualization departs from the Oedipal triangle because Lacan’s structuralist approach is akin to a mobile topology in which triangulation occurs in every direction — the elements in the chain are constantly shifting positions. Therefore, Lacan articulates his structural model around desire, its object, and the law — each situated in relation to the pure signifier. For every image, there is a specific position of function they occupy — all in relation to lack.

— —

In case of confusion, let’s sum up this progression:

Freud’s framework treats the Mommy-Daddy-Me triangle as grounded in real people — your literal mother and father shape your subjectivity, and everything loops back to them. Lacan, however, reconfigures this structure by detaching it from actual parental figures: it is not the specific people, but rather, the symbolic positions they occupy within a pre-existing structure of language and law. What matters is not who fills the role, but the fact that the role exists within the Symbolic. So instead of me-mommy-daddy, Lacan’s framework is in terms of desire, the object of desire, and the law (3 points). However, Lacan argues that the these terms rely on the placement of the pure signifier within the symbolic chain — and this pure signifier distributes lack to the elements within the chain (+1). Desire, then, is always unfulfilled because it is structurally barred from being fulfilled.

Deleuze and Guattari’s criticism is obvious. Under Lacan’s structuralism, the roles themselves — desire, object, law — preexist their actualization. That is to say, before an object of desire actually appears, the position for the “object of desire” is already in place. Therefore, lack is arbitrarily deemed a priori — the structure demands its existence.

Paragraph Two

Deleuze and Guattari continue:

It is certain that the two preceding modes of generalization attain their full scope only in structural interpretation. (AO, 52)

This sentence refers back to the preceding discussion of the two key generalizations performed by psychoanalysis. The first involves the extension of the Oedipus complex beyond its traditional familial configuration into pre-, para-, and exo-oedipal formations — which was illustrated by the example of the schizophrenic whose resistance to oedpialization is reinterpreted through the positions of the grandparents. The second involves Lacan’s abstraction of Freud’s Oedipus into a symbolic structure that effectuates the entire social field. These generalizations can only occur under a structuralist framework, which privileges positions and functions that preexist the individuals who come to occupy these very positions. They write:

Structural interpretation makes Oedipus into a kind of universal Catholic symbol, beyond all the imaginary modalities. (AO, 52)

By describing Oedipus as a “universal Catholic symbol,” Deleuze and Guattari argue psychoanalysis positions Oedipus as a central structure by which subjectivity is shaped. Rather than understanding Oedipus purely as fantasy, structural interpretations conceptualize Oedipus as a structural condition of subjectivity where positions are predetermined prior to their actualization. The specific images and figures related to the Imaginary that fill these positions lose their significance — what matters is that the roles exist primarily. They explain:

[Structural interpretation] makes Oedipus into a referential axis not only for the pre-oedipal phases, but also for the para-oedipal varieties, and the exo-oedipal phenomena. (AO, 52)

As discussed above, the structuralist approach transforms Oedipus into a universal framework defined by positions and functions, ensuring that all aspects of desire and subjectivity ultimately refer back to Oedipus. The term “referential axis” indicates that Oedipus becomes the central point of reference — even the so-called “pre-oedipal phases” presuppose the subject’s inevitable oedipalization, while the “para-oedipal varieties” (various syndromes that remain parallel to Oedipus) and “exo-oedipal phenomena” (formations of psychosis) are also folded back into the Oedipal structure.

Deleuze and Guattari continue:

The notion of “foreclosure,” for example, seems to indicate a specifically structural deficiency, by means of which the schizophrenic is of course repositioned on the Oedipal axis, set back into the Oedipal orbit in the perspective, for example, of the three generations, where the mother was not able to posit her desire toward her own father, nor the son, consequently, toward the mother. (AO, 52)

In psychoanalysis, it is important to distinguish between repression and foreclosure:

- Repression is associated with the neurotic structure, where the neurotic subject pushes certain thoughts and feelings into the unconscious as a defense mechanism. The repressed material, however, returns to consciousness in the form of displacement where the neurotic subject redirects these negative thoughts and feelings onto something else. Or, this repressed material returns to consciousness via various symptoms related to one’s behavior.

- Foreclosure is associated with the psychotic structure, where the psychotic subject does not allow signifiers to enter the Symbolic. The psychotic forecloses these signifiers entirely. Most notably, the Name-of-the-Father — which represents law, prohibition, and symbolic authority — is excluded from the symbolic chain altogether. This leaves the psychotic divorced from the organizing structure of language and law which results in hallucinations, delusions, and what is clinically recognized as schizophrenia.

In the quote above, Deleuze and Guattari highlight that Lacan’s concept of foreclosure indicates a “structural deficiency,” wherein the schizophrenic’s foreclosure of signifiers prevents signifiers pertaining to law and language (particularly the Name-of-the-Father) to enter the Symbolic. Specifically, in the case of schizophrenia, Lacan views psychosis as a structural category that paranoia and schizophrenia fall under. For Lacan, schizophrenia is a particular psychotic phenomena, with the failure to properly integrate the Name-of-the-Father into the symbolic resulting in a subject closed off from reality (language and meaning fall apart). Deleuze and Guattari, however, explain that the psychoanalyst seeks to reposition the schizophrenic within the Oedipal axis, forcing the schizophrenic back into the “Oedipal orbit” by situating them in the context of a grandparental constellation (which was explained earlier).

To understand the notion of foreclosure in terms of psychosis, I recommend this video. I intend to eventually write a post on Seminar III, but this video is quite good in the meantime.

To continue:

One of Lacan’s disciples writes: we are going to consider “the means by which the Oedipal organization plays a role in psychoses; next, what the forms of psychotic pregenitality are and how they are able to maintain the Oedipal reference.” (AO, 52)

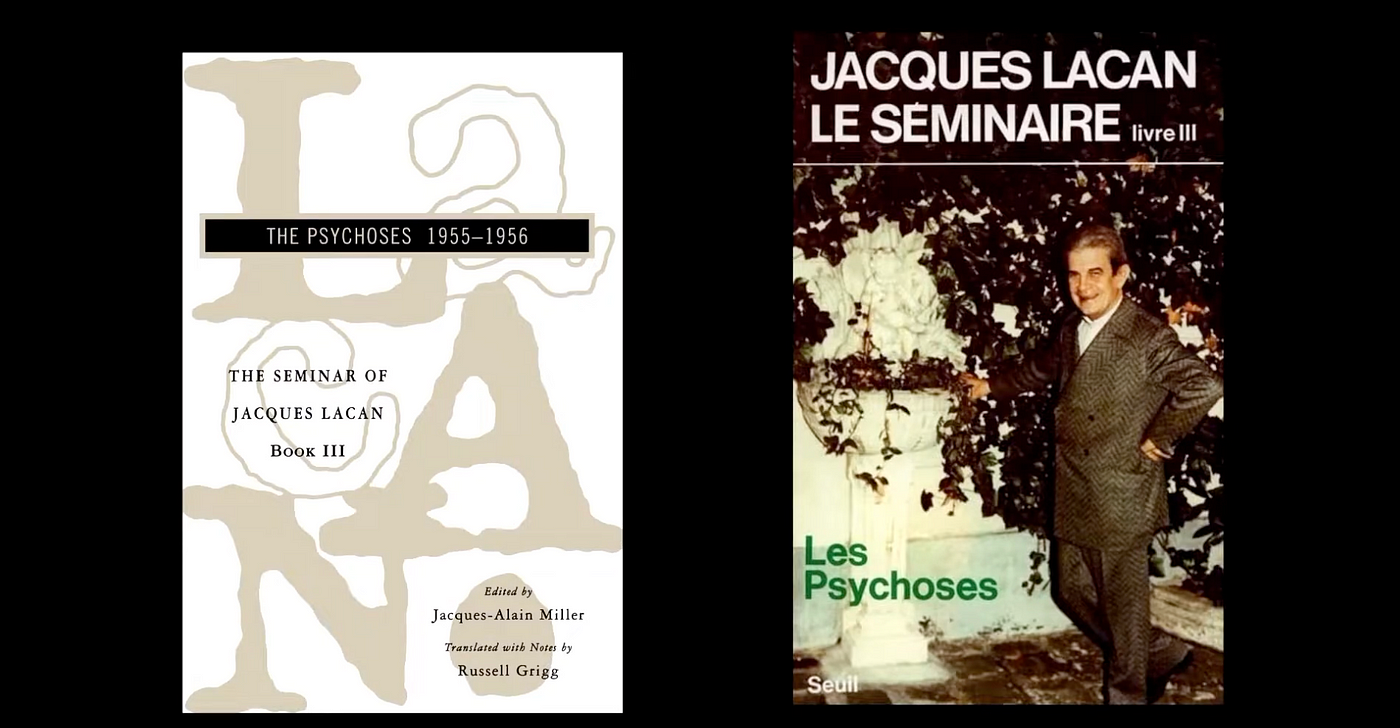

Deleuze and Guattari refer to one of “Lacan’s disciple[s]” through an unattributed citation, likely referencing XYZ. In the quoted passage, XYZ isolates the persistence of Oedipal organization within psychotic subjects. This concept is most clearly developed in Lacan’s Seminar III: The Psychoses. For Lacan, psychosis results from the foreclosure of the Name-of-the-Father (it is prevented entry into the symbolic chain), yet Lacan nevertheless attempts to trace remnants of the Oedipal structure in psychoses, particularly in pregenital or pre-oedipal stages. Ironically enough, the Oedipal reference remains even when it is foreclosed.

Deleuze and Guattari write:

Our preceding criticism of Oedipus therefore risks being judged totally superficial and petty, as if it applied solely to an imaginary Oedipus and aimed at the role of parental figures, without at all penetrating the structure and its order of symbolic positions and functions. (AO, 52)

They conclude this second paragraph by clarifying that their critique is neither superficial nor petty; Deleuze and Guattari are not merely attacking the imaginary figures of the mother and father. Rather, they are challenging the very structural foundations of psychoanalysis, specifically its structural interpretations that impose a reductive Oedipal framework onto the unconscious.

Paragraph Three

Deleuze and Guattari continue:

For us, however, the problem is one of knowing if, indeed, that is where the difference enters in. (AO, 52)

This quote questions whether the real difference or rupture lies between the Imaginary and Symbolic registers or elsewhere. In Lacan’s account, the true difference emerges in the transition between these two registers — as the subject moves from an illusory sense of unity to a split state. They rightfully question this Lacanian notion of difference:

Wouldn’t the real difference be between Oedipus, structural as well as imaginary, and something else that all the Oedipuses crush and repress: desiring-production — the machines of desire that no longer allow themselves to be reduced to the structure any more than to persons, and that constitute the Real in itself, beyond or beneath the Symbolic as well as the Imaginary? (AO, 52–53)

When we examine Oedipus — whether through Lacanian structuralism, where it is inscribed in the Symbolic order, or through the classical Freudian lens of imaginary identifications with the mother and father — it becomes clear that the true difference cannot be between the Symbolic and the Imaginary as they are both stuck within the Oedipal framework. Instead, the true difference is between Oedipus itself and something that Oedipus seeks to “crush and repress”: desiring-production. Desiring-machines themselves constitute the Real — and the true difference that ought to be examined is between the Real and the artificially produced domains of the Symbolic and the Imaginary.

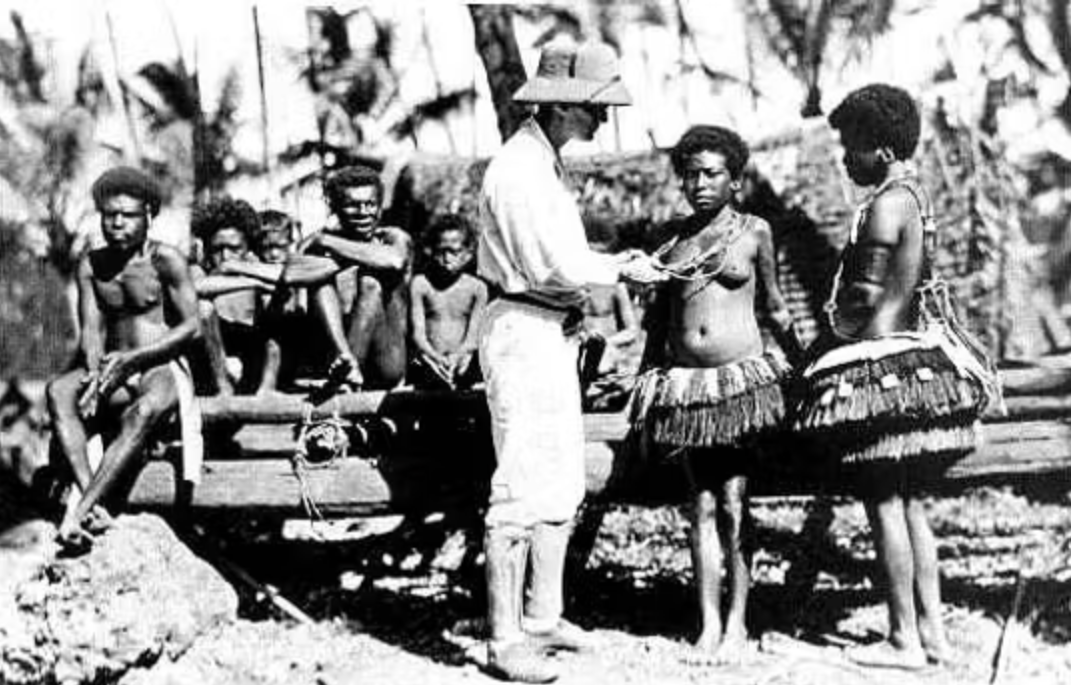

We in no way claim to be taking up an endeavor such as Malinowski’s, showing that the figures vary according to the social form under consideration. (AO, 53)

Deleuze and Guattari reference Polish anthropologist Bronisław Malinowski to clarify that their critique of psychoanalysis is not simply akin to an anthropological relativism that Malinkowski studied. In his 1927 work Sex and Repression in Savage Society, Malinowski showed that familial roles — such as mother, father, child, and so on — vary depending on the society in question. Although Malinowski rejected Freud’s notion of a universal Oedipus complex, he nonetheless preserved the assumption of a family drama: the content may change, but the structural form remains intact. In this sense, Malinowski is to anthropology as Lacan is to psychoanalysis.

Here is an article to help clarify Malinowski’s position:

Malinowski proposed that the matrilineal configuration of the Trobriand family cast a boy’s mother’s brother rather than his father in the role of resented authority figure, and his sister rather than his mother as the object of a boy’s incestuous desire. (The Public Domain Review)

Lacan’s perspective on the family differs from Malinowski’s. Lacan views the family structure in rigid manner (always mommy-daddy-me), whereas Malinkowski highlights that different societies have varying configurations of family structures. The main problem between the two lies in the recognition that Lacan and Malinowski share a universal structure. No matter the viewpoint, this structure is made up of images that occupy specific positions and functions within a chain of signifiers.

Deleuze and Guattari write:

We even believe what we are told when Oedipus is presented as a kind of invariant. (AO, 53)

Even if Oedipus appears across different cultures and historical periods, Deleuze and Guattari stand by their criticism. Its recurrence does not prove that Oedipus is a priori; rather, this recurrence reveals the extent to which Oedipal structures have repressed desiring-production throughout various societies.

Deleuze and Guattari proceed by raising several questions:

But the question is altogether different: is there an equivalence between the productions of the unconscious and this invariant — between the desiring-machines and the Oedipal structure? (AO, 53)

This first question asks whether there is a genuine equivalence between desiring-machines — “the productions of the unconscious” — and the invariant of structure of Oedipus. Ultimately, Deleuze and Guattari question whether what the unconscious produces is already structured as Oedipus. They continue to ask:

Or rather, does not the invariant merely express the history of a long mistake, throughout all its variations and modalities; the strain of an endless repression? (AO, 53)

This second question is evidently rhetorical, suggesting that Oedipus is not equivalent to the productions of the unconscious but rather a historical mistake. If this is the case, Oedipus would be a mistake that has led to an “endless repression.”

They make clear what they are calling into question:

What we are calling into question is the frantic Oedipalization to which psychoanalysis devotes itself, practically and theoretically, with the combined resources of image and structure. (AO, 53)

- In the original French text, “Oedipalization” is not capitalized.

Deleuze and Guattari’s primary criticism focuses on how psychoanalysis faithfully relies on Oedipus to “frantic[ally] oedipaliz[e]” everything, subsuming all desire within the Oedipal framework. They argue that psychoanalysis accomplishes this practice of oedipalization both practically — through clinical practice and the imposition of psychiatric methods on the analysand — and theoretically, through its psychoanalytic writings and conceptual frameworks. This process is reinforced by the “resources of image and structure” — the Imaginary and the Symbolic — which ultimately traps desire by situating every image within a pre-given position and function. They explain:

And despite some fine books by certain disciples of Lacan, we wonder if Lacan’s thought really goes in this direction. (AO, 53)

It is evident that Deleuze and Guattari give credit where credit is due. There have been some wonderful writings provided by “disciples of Lacan,” but Deleuze and Guattari question whether Lacan’s thought truly goes in the direction of dismantling or challenging Oedipus. They ask:

Is it merely a matter of oedipalizing even the schizo? (AO, 53)

As we have seen, psychoanalysis takes up the schizo — precisely the figure who most visibly resists Oedipus — and interprets them as a subject related to the Oedipus in some manner. Deleuze and Guattari ask whether this is truly the end goal, or if another path is possible:

Or is it a question of something else, and even the contrary?* (AO, 53)

*The footnote here says:

“Nevertheless, it is not because I preach a return to Freud that I am not able to say that Totem and Taboo is a twisted story. It is in fact for that reason that we must return to Freud. No one helped me to make this known: the formations of the unconscious. . . . I am not saying Oedipus serves no purpose, nor that it (ça) bears no relationship with what we do. It serves no purpose for the psychoanalysts, that is indeed true! But since psychoanalysts are assuredly not psychoanalysts, that proves nothing. . . . These are things I set forth in their appropriate time and place; that was a time when I was speaking to people who had to be dealt with tactfully — psychoanalysts. On that level, I spoke of the paternal metaphor, I have never spoken of an Oedipus complex.” (Jacques Lacan in a seminar, 1970.)

- The French word “ça” means both “it” and “Id.” Lacan use of the term appears to be a doubling here to note that both Oedipus and the Id are not solely divorced from the psychoanalytic work he does.

This footnote references Lacan’s Seminar XVII, where he makes a significant departure from Freud’s Oedipus complex. He discusses Freud’s 1913 text Totem and Taboo, which he describes as a “twisted story.” While Lacan emphasizes his return to Freud, he is clear that this return does not entail endorsing everything Freud wrote; these very inconsistencies in Freud’s works are what Lacan seeks to examine. Although Lacan discards the Oedipus complex in its traditional Freudian form, he does so in a nuanced way: he criticizes its institutionalized use by psychoanalysts, yet retains aspects of its structural function via the paternal metaphor. When Lacan says that the Oedipus complex “serves no purpose for the psychoanalysts,” while immediately saying that “psychoanalysts are assuredly not psychoanalysts,” he is isolating how many psychoanalysts have failed to conceptualize Freud’s insights — they have failed to critically examine Freud.

Deleuze and Guattari are asking whether Lacan is truly departing from Oedipus. On one hand, they recognize that Lacan is ambivalent and deeply critical of the Oedipus complex. On the other hand, he is dependent on Freud and adheres to the structural framework of Oedipus with his paternal metaphor.

Regardless, Deleuze and Guattari posit a different cure:

Wouldn’t it be better to schizophrenize — to schizophrenize the domain of the unconscious as well as the sociohistorical domain, so as to shatter the iron collar of Oedipus and rediscover everywhere the force of desiring-production; to renew, on the level of the Real, the tie between the analytic machine, desire, and production? (AO, 53)

Instead of oedipalizing the schizo, Deleuze and Guattari ask if schizophrenization would be a better alternative. This is the first use of “schizophrenization” in Anti-Oedipus, and given the context, we can understand it as a process of dismantling the Oedipal framework — or rather, any framework — which restrains the unconscious and sociohistorical domain. To “shatter the iron collar of Oedipus” and to remove its chains is to “rediscover everywhere the force of desiring-production. Schizophrenization is deemed a liberating process that frees desire from its familial symbolism. Deleuze and Guattari employ the term “analytic machine” which denotes that even psychoanalysis must be understood in a machinic manner — with this machinery not indicating anything symbolic; they want to tie this analytical machine to the process of desiring-production.

They write:

For the unconscious itself is no more structural than personal, it does not symbolize any more than it imagines or represents; it engineers, it is machinic. (AO, 53)

Once again, in the same vein that the unconscious is not concerned with global persons, it is not concerned with structural interpretations. The unconscious does not symbolize or represent anything. The unconscious is constantly is understood solely in terms of machines:

Neither imaginary nor symbolic, it is the Real in itself, the “impossible real” and its production. (AO, 53)

The unconscious is “neither imaginary nor symbolic.” It is not concerned with images or symbols, but it entirely composed of the Real — it is the Real. The term “impossible real” is a pointed critique of Lacan, who argues that the Real is entirely inaccessible. However, this so-called “impossible real” is, in fact, always possible, as the unconscious itself is the Real and its continuous production.

Paragraph Four

Deleuze and Guattari continue:

But what is this long history, if we consider it only during the period of psychoanalysis? (AO, 53)

They begin by positing a rhetorical question regarding the “long history” of psychoanalysis (spoiler: it has not been a very long history). However, they are saying that even if we limit our focus to this relatively short history, it is still pertinent to examine the development of Oedipus. They write:

[This “long history”] does not take place without doubts, detours, and repentances. (AO, 53)

It is quite clear that in the period of psychoanalysis that details the development of Oedipus, Freud himself was hesitant. Deleuze and Guattari explain:

Laplanche and Pontalis note that Freud “discovers” the Oedipus complex in 1897 in the course of his self-analysis, but that he doesn’t give a generalized theoretical form to it until 1923, in The Ego and the Id, and that, between these two formulations, Oedipus leads a more or less marginal existence, “confined for example to a separate chapter on object-choice at puberty (Three Essays), or to a chapter on typical dreams (The Interpretation of Dreams).” (AO, 53)

Deleuze and Guattari reference Jean Laplanche and Jean-Bertrand Pontalis’ 1964 text Fantasme originaire, fantasmes des origines et origine du fantasme, which has not been translated into English. Nevertheless, the general claim is that Freud first formulated the concept of the Oedipus complex in 1897 (with his “self-analysis”) and it remained relatively marginal in his work for decades. Deleuze and Guattari highlight Laplanche and Pontalis’ observation that Oedipus occupied a “more or less marginal existence” in Freud’s early writings. According to Laplanche and Pontalis, the Oedipus complex takes root only briefly in a single chapter of The Interpretation of Dreams (1899) and is a bit more developed in Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality (1905), particularly in relation to infantile sexuality and the emergence of “object-choice” during puberty. (“Object-choice at puberty” is when a subject’s sexual drives are directed towards external figures.) It is in The Ego and the Id (1923) that Freud fully integrates the Oedipus complex into the model of the psyche.

Deleuze and Guattari write:

[Laplanche and Pontalis] say that this is because a certain abandonment by Freud of the theory of traumatism and seduction leads not to a univocal determination of Oedipus, but to the description as well of a spontaneous infantile sexuality of an endogenous nature. (AO, 53–54)

In the mid-1890s, Freud’s understanding of neurotic symptoms in adults was based on his theory of traumatism and seduction — which refer to early encounters a child might have with sexual experiences, particularly sexual abuse. Freud argued that these premature sexual experiences overwhelmed the child’s ability to process and integrate such events. However, as Laplanche and Pontalis point out, Freud’s abandonment of the theory of traumatism and seduction did not immediately result in “univocal determination of Oedipus.” In fact, as Freud departed from the seduction theory in the late 1890s, the Oedipus complex remained a marginal concept for decades. Instead of focusing on external trauma, Freud’s immediate shift was a new understanding of the child as possessing an “endogenous nature,” indicating that certain sexual drives are intrinsic to natural development.

Deleuze and Guattari continue by directly citing Laplanche and Pontalis’ Fantasme originaire, fantasmes des origines et origine du fantasme:

It is as if “Freud never managed to articulate the interrelations of Oedipus and infantile sexuality,” the latter referring to a biological reality of development, the former to a psychic fantasy reality. Oedipus is what all but got lost “for the sake of a biological realism.” (AO, 54)

Laplanche and Pontalis suggest that Freud essentially failed to analyze the relationship between the Oedipus complex and infantile sexuality. Oedipus refers to “psychic fantasy,” while the infant’s sexuality is grounded in biological development — something tangible and real. In fact, Freud’s initial relationship to Oedipus was sidestepped in favor of biological realism. However, Freud still clung to Oedipus. This is the crux of Deleuze and Guattari’s criticism: Freud never established the connection between the biological reality of the child’s development (the “endogenous nature”) and the psychic fantasy of the Oedipus complex. It is as if Freud arbitrarily assumed these dimensions were intrinsically related without actually demonstrating how.

Paragraph Five

To continue, Deleuze and Guattari posit some questions:

But is it correct to present things in this way?

Did the imperialism of Oedipus require only the renunciation of biological realism?

Or wasn’t something else sacrificed to Oedipus, something infinitely stronger? (AO, 54)

They question whether their analysis in the preceding paragraph was the true trajectory of Freud. Is Freud’s letting go of biological realism in favor of Oedipus responsible for the imperialism of Oedipus? Or is there a deeper sacrifice — a potential discarding of the operationalization of desire itself? Deleuze and Guattari explain:

For what Freud and the first analysts discover is the domain of free syntheses where everything is possible: endless connections, nonexclusive disjunctions, nonspecific conjunctions, partial objects and flows. (AO, 54)

To clarify, Deleuze and Guattari are not suggesting the Freud was entirely mistaken. They credit Freud and the early analysts with the discovery the “domain of free syntheses” (“endless connections” refer to the first synthesis, “nonexclusive disjunction” refer to the second synthesis, and “nonspecific conjunctions” refer to the third synthesis). They write:

The desiring-machines pound away and throb in the depths of the unconscious: Irma’s injection, the Wolf Man’s ticktock, Anna’s coughing machine, and also all the explanatory apparatuses set into motion by Freud, all those neurobiologico-desiring-machines. (AO, 54; emphasis mine)

Deleuze and Guattari isolate several of Freud’s case studies to illustrate how the domain of free syntheses is manifested in Freud’s practice. For Freud, these cases were not initially reduced to Oedipus, but instead a production of neurobiologico-desiring-machines. The term “neurobiologico-machines” refers to the study of neurobiology pertaining to how the brain functions. Freud initially offered a reasonably coherent understanding of the function of these machines.

Sit on the couch…

Irma’s injection

Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams includes several dreams of his own, accompanied by detailed analysis of each of his dreams. One of the most prominent dreams is known as Irma’s Injection, which occurred on the night of July 23–24, 1895. In the dream, Freud encounters a former patient, Irma, who appears physically ill. He inspects her throat and sees white patches which prompts him to call Dr. M. During Dr. M.’s examination, Freud’s friends Otto and Leopold are present — Otto appears sickly, while Leopold “percusses her covered chest.” In the dream, it is revealed that Otto had previously given Irma an injection in effort to cure her, which is the supposed cause of her illness.

Freud finds this dream to have particular advantages in terms of analysis:

This dream has an advantage over many others. It is at once obvious to what events of the preceding day it is related, and of what subject it treats. The preliminary statement explains these matters. The news of Irma’s health which I had received from Otto, and the clinical history, which I was writing late into the night, had occupied my psychic activities even during sleep. (The Interpretation of Dreams)

Throughout his interpretation, Freud carefully traces how the dream’s setting, characters, and event connect to previous experiences, thoughts, and emotions — specifically from the day before. For example, the “great hall” where the dream takes place corresponds to his summer residence in Bellevue. Irma — a former patient of Freud’s — had recently been described by Otto as “better, but not quite well” — a report that Freud disliked. Furthermore, Freud reads the event of Otto administrating Irma’s injection as displacement of his own feelings; he no longer feels guilty about his failure to cure Irma as that blame becomes displaced onto Otto.

What is most important here is that Freud, in his earlier stages, does not interpret the dream through the lens of an organizing principle (such as Oedipus). Instead, Freud engages with the dream as a series of associative breaks linked to previous experiences.

Wolf Man’s ticktock

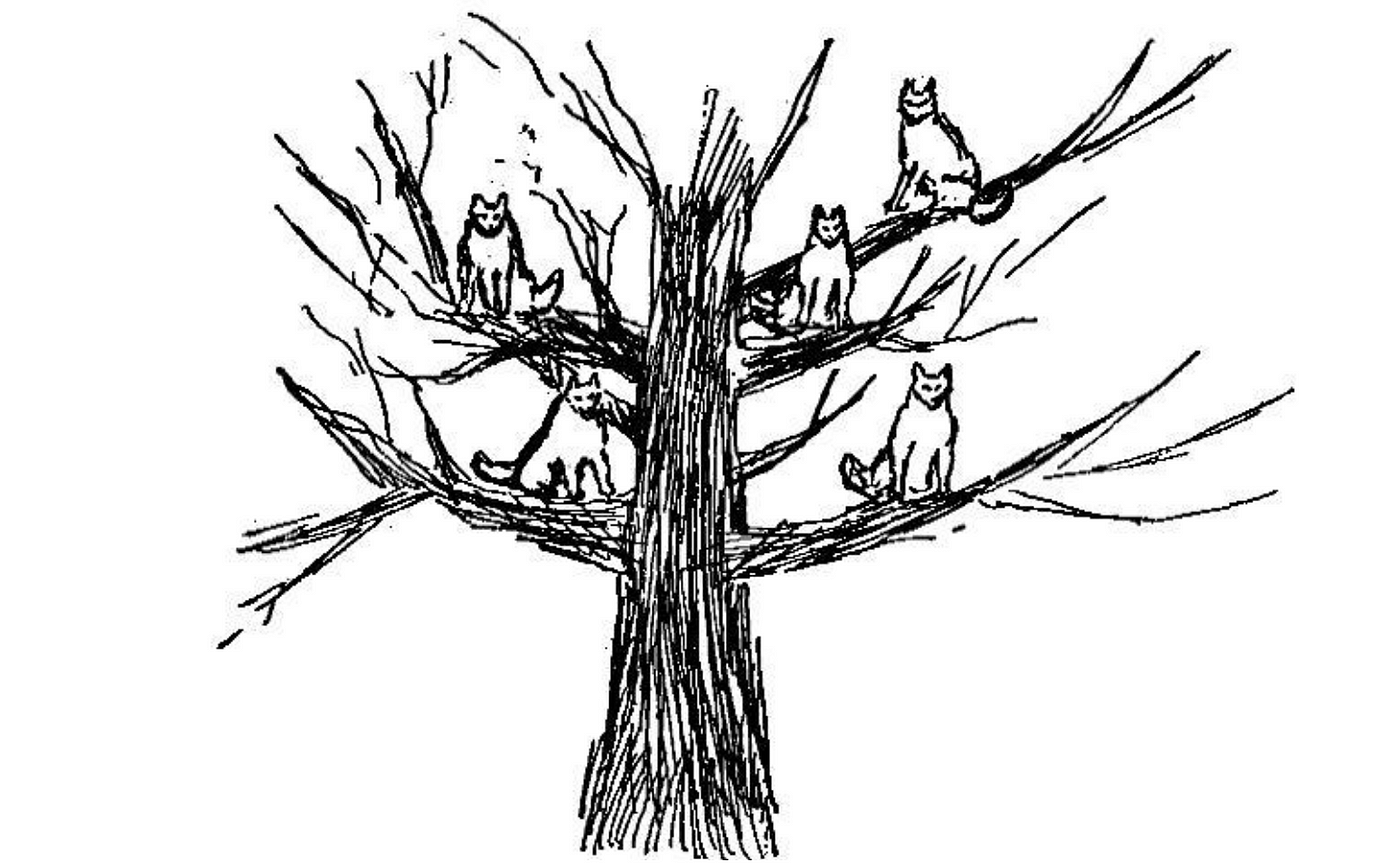

Freud’s 1918 work From the History of Infantile Neurosis examines the case of the Sergei Pankejeff, a Russian aristocrat who approached Freud for treatment. One cold winter night as a child, Pankejeff had a vivid dream, which he later recalled to Freud. Over the years of their work together, Freud focused on interpreting this dream and Freud even assigned Pankejeff the pseudonym ‘Wolf Man’ based on the dream’s content. Pankejeff describes the dream in detail, particularly in the fourth section of the book, titled The Dream and the Primal Scene:

“I dreamt that it was night and that I was lying in my bed. (My bed stood with its foot towards the window; in front of the window there was a row of old walnut trees. I know it was winter when I had the dream, and night-time.) Suddenly the window opened of its own accord, and I was terrified to see that some white wolves were sitting on the big walnut tree in front of the window. There were six or seven of them. The wolves were quite white, and looked more like foxes or sheep-dogs, for they had big tails like foxes and they had their ears pricked like dogs when they pay attention to something. In great terror, evidently of being eaten up by the wolves, I screamed and woke up.” (From the History of Infantile Neurosis)

Freud rigorously interprets Pankejeff’s dream, drawing on a range of Pankejeff’s lived experiences. He notes that the presence of six or seven wolves may allude to the children’s story The Wolf and the Seven Little Goats that Pankejeff was familiar with as a child. In this story, the wolf devours one of the goats, reducing the number from seven to six. Freud also associates the wolves to another childhood story told to Pankejeff by his grandfather, in which a tailor pulls off a wolf’s tail, causing the wolf to flee. Freud interprets the fox-like tails of the wolves in the dream as symbolic of the missing tail in the grandfather’s story. Further in the story, the tailor walks in the forest and encounters a pack of wolves, to which he climbs up a tree to escape. Freud notices that, in the dream, the wolves are in the tree, so he finds a unique tie between the grandfather’s story and Pankejeff’s dream. Additionally, the tree in the dream is identified by Pankejeff as a Christmas tree, and since his birthday falls on Christmas Day, Freud not only associates the tree in the dream to Christmas, but also finds that this dream must have occurred just before Pankejeff’s fourth birthday.

Though Freud suggests that the wolf symbolizes Pankejeff’s father, his analysis is not a simple reduction of all elements in the story to parental figures. Instead, Freud engaged in an attempt to conceptualize the broader lived experience of Pankejeff in order to explain how unconscious associations appear in the dream. This case study was right before Freud’s faithful commitment to the Oedipus complex, so Deleuze and Guattari praise Freud for a more comprehensive analysis than a solely reductive approach.

When Deleuze and Guattari speak of the Wolf Man’s “tick-tock,” this could refer to a couple things:

- The likely reference: In the fairy tale The Wolf and the Seven Little Goats, the youngest goat escapes the wolf by hiding in a clock-case. In the case study we are analyzing, Freud notes that Pankejeff was positioned on a couch facing opposite a large grandfather clock, while simultaneously facing away from Freud. During sessions, Pankejeff would often turn his head back and forth — first toward the clock, then toward the analyst — in a rhythm resembling a tick-tock. Pankejeff eventually gave Freud an explanation for this tick-tock movement, telling Freud of the story of The Wolf and the Seven Little Goats. Freud interpreted this as Pankejeff viewing the analyst in the role of the wolf, and Pankejeff, like the little goat, was contemplating whether he needed to hide.

- The unlikely reference: Five o’clock marks a recurring point of crisis in the patient’s life — a time associated with fevers in childhood, and later with inexplicable bouts of depression. This hour, Freud notes, is possibly linked to an early moment of Pankejeff witnessing his parents having sexual intercourse in an ‘animalistic’ position. This hour repeats — tick-tock, tick-tock — and becomes repetitive in the body’s memory.

Anna’s coughing machine

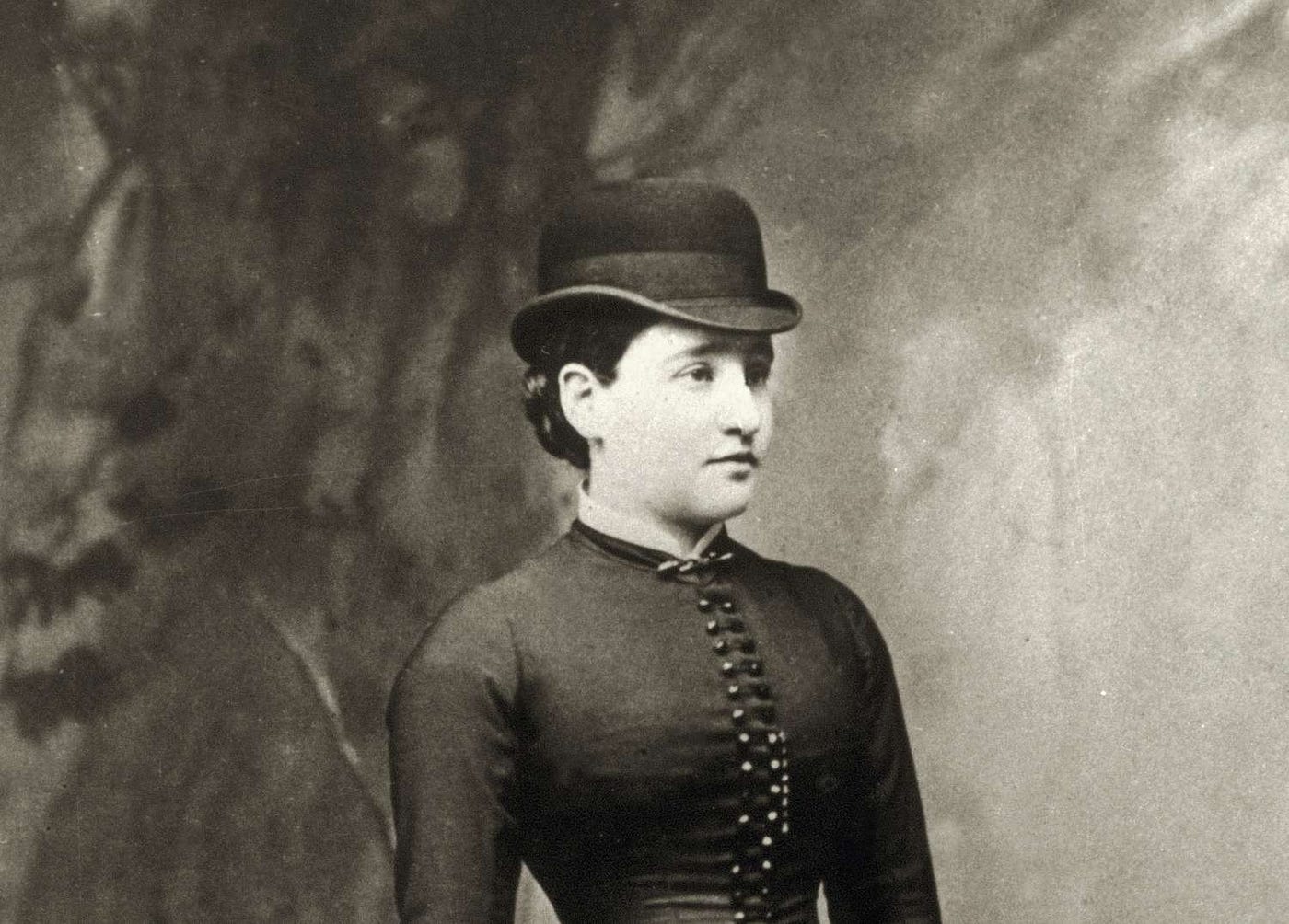

Freud and his colleague, Austrian psychoanalyst Josef Breuer, published their collaborative work Studies on Hysteria in 1895. This text presents a series of case studies centered on the concept of hysteria — a term which, at the time, referred to a disorder characterized by neurological symptoms and dysregulated emotional behavior, often accompanied by physical ailments.

One of the most well-known cases in the text is that of Anna O. Freud immediately outlines his analysis of her condition in four distinct phases, beginning in 1880 and concluding with the cessation of her illness in 1882. He describes Anna O. as a brilliant woman — intelligent, articulate, and intellectually curious. Freud notes that she did not appear to have psychological conflicts related to her sexuality, so he ruled out sexual factors playing a role in her condition. While he observed a hereditary predisposition to neurosis in Anna O.’s family, Freud emphasizes that her hysterical symptoms were not necessarily congenital. Rather, they emerged after her father fell seriously ill in 1880, an event that deeply affect her as she took on the intense responsibility of caring for him. Freud writes:

During the first months of the illness Anna devoted her whole energy to nursing her father, and no one was much surprised when by degrees her own health greatly deteriorated. No one, perhaps not even the patient herself, knew what was happening to her; but eventually the state of weakness, anaemia and distaste for food became so bad that to her great sorrow she was no longer allowed to continue nursing the patient. The immediate cause of this was a very severe cough, on account of which I examined her for the first time. (Studies on Hysteria)

Anna O. exhibited a wide range of physical symptoms, including a persistent cough, a convergent squint (diplopia), and muscular stiffness. She experienced pain and restricted movement throughout her body — whether in her neck, arms, eyes, or throat, her condition steadily worsened. Without going into too much detail of her symptoms, it is evident she was a unique case study for Freud. Over time, Freud met with her regularly, attempting to understand the why behind her symptoms. He eventually concluded that her symptoms were closely tied to the emotional trauma of her father’s illness and eventual death.

Freud observed that when Anna O. was able to identify the root cause of a specific symptom — specifically, the first time it occurred and why — she would begin to recover. Consider, for example, her persistent cough:

She began coughing for the first time when once, as she was sitting at her father‘s bedside, she heard the sound of dance music coming from a neighbouring house, felt a sudden wish to be there, and was overcome with self-reproaches. (Studies on Hysteria)

Anna O.’s coughing symptoms first emerged while she was sitting beside her ailing father and heard dance music playing from a neighbor’s house. As someone who loved dancing, she desperately wanted to attend the neighbor’s party. This resulted in her feeling sick and as she developed a cough. Freud found the connection between the neighbor’s music and Anna O’s cough to be intriguing as even Anna O. herself did not fully understand how these two were associated with one another. Freud explains:

The patient could not understand how it was that dance music made her cough; such a construction is too meaningless to have been deliberate. (It seemed very likely to me, incidentally, that each of her twinges of conscience brought on one of her regular spasms of the glottis and that the motor impulses which she felt — for she was very fond of dancing — transformed the spasm into a tussis nervosa.) (Studies on Hysteria)

Instead of reducing each symptom to something completely arbitrary, Freud sought to analyze the different experiences occurring in Anna O.’s life in order to draw a connection between her neurobiologico-machines and what her experiences at the time of her father’s illness.

Rather than reducing each symptom to some arbitrary concept, Freud sought to analyze the specific experiences in Anna O.’s life, particularly those surrounding her father’s illness, in order draw connections between her neurobiologico-machines, physical ailments, and experience as a caretaker.

Get off the couch…

Deleuze and Guattari reference these three example from Freud’s work to emphasize that early Freud was on the right track. He analyzed the neurobiologico-machines of the unconscious rather than reducing everything to an arbitrary Oedipal framework.

To continue:

And the discovery of the productive unconscious has what appear to be two correlates: on the one hand, the direct confrontation between desiring-production and social production, between symptomological and collective formations, given their identical nature and their differing regimes; and on the other hand, the repression that the social machine exercises on desiring-machines, and the relationship of psychic repression with social repression. (AO, 54)

Deleuze and Guattari note that the discovery of the productive unconscious is essential in early Freud. In their analysis, the productive unconscious has two correlates:

- The first correlate is a direct confrontation between desiring-production and social production. At the level of desiring-production, there are symptomological formations (symptoms), while at the level of social production, there are collective formations or group fantasies. Though these two operate in different regimes, they are fundamentally identical.

- The second correlate is that social production represses desiring-production; technical and social machines exercise repression on desiring-machines. This repression produces psychic repression, meaning that the individuals’ psychic repression cannot be divorced from the social sphere. Psychic repression was always social repression.

The case studies examined by Freud above — such as Irma’s injection, Pankejeff’s dream, or Anna O.’s symptoms — cannot solely be conceptualized at the level of psychic repression that is divorced from social production. Freud’s early discoveries and case studies understood this. However, Freud falls ends up falling short:

This will all be lost, or at least singularly compromised, with the establishment of a sovereign Oedipus. (AO, 54)

As the title of the book suggests, the establishment of Oedipus as the universal symbol of desire in Freud’s work compromises the true discovery of the productive unconscious. Deleuze and Guattari write:

Free association, rather than opening onto polyvocal connections, confines itself to a univocal impasse. (AO, 54)

In psychoanalysis, free association refers to the practice in which a patient freely shares thoughts, ideas, or emotions that come to mind without censorship, supposedly exposing the workings of the unconscious. While this method might appear to view the unconscious as productive, psychoanalysis adheres to its reductive approach. Rather than understanding these associations as part of an open-ended, polyvocal system, psychoanalysis channels them back into a single interpretive axis: the sovereign Oedipus. Thus, a univocal meaning is imposed on the patient’s speech.

Furthermore:

All the chains of the unconscious are biunivocalized, linearized, suspended from a despotic signifier. (AO, 54)

No word escapes this univocal impasse as the chains of the unconscious are biunivocalized. Each element in the chain is defined exclusively and must relate to a despotic signifier that distributes lack to each element in the chain. They write:

The whole of desiring-production is crushed, subjected to the requirements of representation, and to the dreary games of what is representative and represented in representation. (AO, 54)

Deleuze and Guattari criticize the representational logic of psychoanalysis. Everything in psychoanalysis serves as a representation of something else. For example, Pankejeff has a dream which must serve as a representation of repressed desire. This repressed desire must serve as a representation of childhood trauma. And, this childhood trauma must serve as a representation of some overarching structure (i.e., Oedipus). The “representative” or the analyst functions as the arbiter which assigns meaning to the content that must be “represented.” The games are dull and dreary because it crushes the entirety of desiring-production:

And there is the essential thing: the reproduction of desire gives way to a simple representation, in the process as well as theory of the cure. (AO, 54)

In psychoanalysis — whether it be the theoretical formulations or the so-called cure — all desire is reduced to representations. The productive capacity of desire is neutralized as it must always be interpreted. Furthermore:

The productive unconscious makes way for an unconscious that knows only how to express itself — express itself in myth, in tragedy, in dream. (AO, 54)

Deleuze and Guattari argue that the productive unconscious is primary — it is a priori. This productive unconscious is what makes way for a model of the unconscious that is understood through interpretation and representation, expressing itself in mythology, tragedy, and dreams.

Paragraph Six

To continue:

But who says that dream, tragedy, and myth are adequate to the formations of the unconscious, even if the work of transformation is taken into account? (AO, 54)

Deleuze and Guattari question who gets to decide that the unconscious properly belongs to the domain of dream, tragedy, and myth. Even if a psychoanalyst admits that the unconscious does not express itself directly through myth, they still claim that unconscious productions undergo an innate transformation — disguising these productions in mythological or symbolic forms. Once again, who authorizes this framework? And on what grounds is it deemed correct? They write:

Groddeck remained more faithful than Freud to an autoproduction of the unconscious in the coextension of man and Nature. (AO, 54)

Deleuze and Guattari reference one of Freud’s influences, the German physician Georg Groddeck, whose analysis conceptualized the unconscious as autoproductive — operating like a factory instead of a theater — as as fundamentally in the coextension of man and Nature. (Groddeck published The Book of the It in 1928, which influenced Freud’s concept of the Id.) For Groddeck, the unconscious was not strictly human, but part of a broader process that blurred the distinction between man and Nature. Deleuze and Guattari state:

It is as if Freud had drawn back from this world of wild production and explosive desire, wanting at all costs to restore a little order there, an order made classical owing to the ancient Greek theater. (AO, 54)

They write that Freud initially understood this “world of wild production and explosive desire,” but ultimately withdrew himself from this perspective. Amidst the apparent chaotic structure of desire, he sought to restore order — an order that resides itself in the ancient Greek theater.

They write:

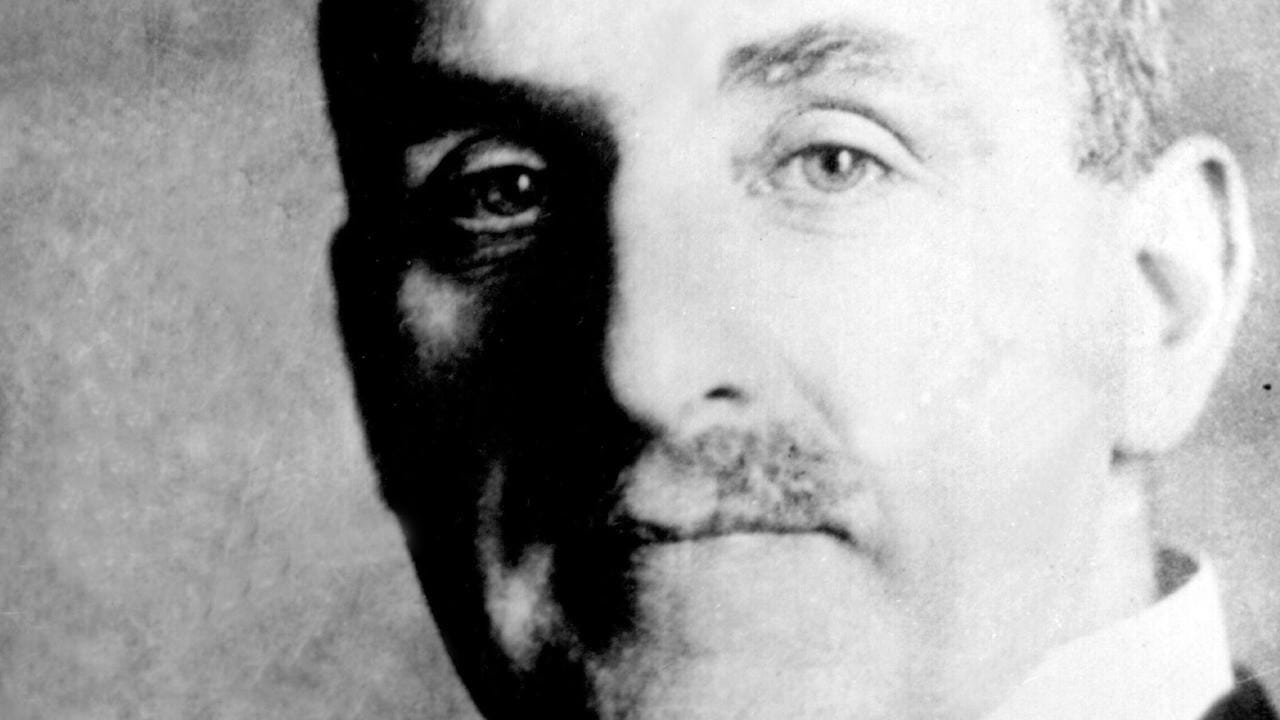

For what does it mean to say that Freud discovered Oedipus in his own self-analysis? Was it in his self-analysis, or rather in his Goethian classical culture? (AO, 55)

Deleuze and Guattari question what it really means for Freud to have “discovered” the Oedipus complex through self-analysis. Did Freud truly identify Oedipus through self-analysis, or did he inherit it from the Western cultural tradition he was steeped in? When they refer to “Goethian classical culture,” they are pointing to the German literary and intellectual environment predominately shaped by figures like Johann Wolfgang von Goethe — an individual influenced by ancient Greek mythology and tragedy. Deleuze and Guattari suggest (with a rhetorical question) that Freud might not have discovered Oedipus in the unconscious, but rather was found within the cultural moment he was situated in.

Furthermore:

In his self-analysis he discovers something about which he remarks: Well now, that looks like Oedipus! (AO, 55)

As Freud embarks upon his self-analysis, he finds things that appear or look like Oedipus. And this appearance becomes what the entire unconscious hinges upon. They write:

And at first he considers this something as a variant of the “familial romance,” a paranoiac recording by which desire causes precisely the familial determinations to explode. (AO, 55)

Initially, Freud understood what would later become the Oedipus complex as a variation of the “familial romance,” a concept he outlines in his brief 1909 essay Family Romances. In this text, Freud describes how a child, after having become disillusioned with their parents, beings to imagine having different, often superior, parents — replacing the real family with fantasized figures of higher status. The child’s imagination, as Freud notes, aims to free them from the authority of their actual parents. When Freud first says, “that looks like Oedipus,” he originally treated this Oedipal-figure as a version of a broader imaginative detachment — a variation of the family romance. Deleuze and Guattari term this moment as a “paranoiac recording,” where desiring-machines repel from the family structure, causing the “familial determinations to explode.”

However, Freud’s approach ultimately became too reductive:

It is only little by little that he makes the familial romance, on the contrary, into a mere dependence on Oedipus, and that he neuroticizes everything in the unconscious at the same time as he oedipalizes, and closes the familial triangle over the entire unconscious. (AO, 55)

Although Oedipus may have initially appeared to Freud as a variation of the familial romance, it eventually became the dominant framework to which the familial romance was subordinated. Freud neuroticized the unconscious — interpreting its formations as expressions of neurosis — and simultaneously oedipalized it, enclosing these formations within the structure of the Oedipal triangle (mommy-daddy-me). In doing so, he created an enemy:

The schizo — there is the enemy! (AO, 55)

The schizo resists this forced oedipalization, marking a deviant that must be explained in terms of Oedipus.

To continue:

Desiring-production is personalized, or rather personologized (personnologisee), imaginarized (imaginarisee), structuralized. (AO, 55)

Unlike Deleuze and Guattari, who view desire as impersonal and productive, the psychoanalyst interprets desiring-production as personalized, or personologized — that is, tied to individual persons. In doing so, the productions of the unconscious are reduced to images that this person relates to (it is imaginarized) and forced into a rigid structure that traps desire into the structural schema of Oedipus (it is structuralized). They comment on these three terms (personologized, imaginarized, structuralized):

(We have seen that the real difference or frontier did not lie between these terms, which are perhaps complementary.) (AO, 55)

Psychoanalysts might claim to establish a distinction between personologization, imaginarization, and structuralization, but Deleuze and Guattari highlight that the fundamental difference is not between these terms because they are, perhaps, complementary. The line psychoanalysts attempt to draw between these terms is arbitrary as they culminate in the same end — the subjugation of the unconscious to representations. They write:

Production is reduced to mere fantasy production, production of expression.

The unconscious ceases to be what it is — a factory, a workshop — to become a theater, a scene and its staging. (AO, 55)

The psychoanalytic model reduces desiring-production to mere fantasy, treating what the unconscious produces as a representation or symbolic expression of something else. Instead of viewing the unconscious as a factory — constantly producing and aligning with the three syntheses — psychoanalysis treats the unconscious as a theater, where scenes take place on stage, awaiting interpretation. Deleuze and Guattari write:

And not even an avant-garde theater, such as existed in Freud’s day (Wedekind), but the classical theater, the classical order of representation. (AO, 55)

The theatrical model Freud relies on is not even a creative or innovative one. In Freud’s time, the avant-garde theater was gaining traction as exemplified by German playwright Frank Wedekind, known for his provocative works like The Awakening of Spring (1891) that challenged the societal repression of adolescent sexuality. Despite the existence of avant-garde theater in his time, Freud aligns with the rigid, classical theater.

Deleuze and Guattari conclude this paragraph by saying:

The psychoanalyst becomes a director for a private theater, rather than the engineer or mechanic who sets up units of production, and grapples with collective agents of production and antiproduction. (AO, 55)

As Deleuze and Guattari explain, the psychoanalyst functions like a stage director, treating the unconscious as a theater to be interpreted. Every part of the productive unconscious is reduced to a nightly performance of the same play: Oedipus. In contrast, Deleuze and Guattari highlight the figure of the engineer or mechanic — the individual who understands the productive unconscious — and understands how to handle the “collective agents of production and antiproduction.” (To clarify, the agents of production refer to the desiring-machines, along with social and technical machines, that production the body without organs as antiproduction.)

Paragraph Seven

To continue:

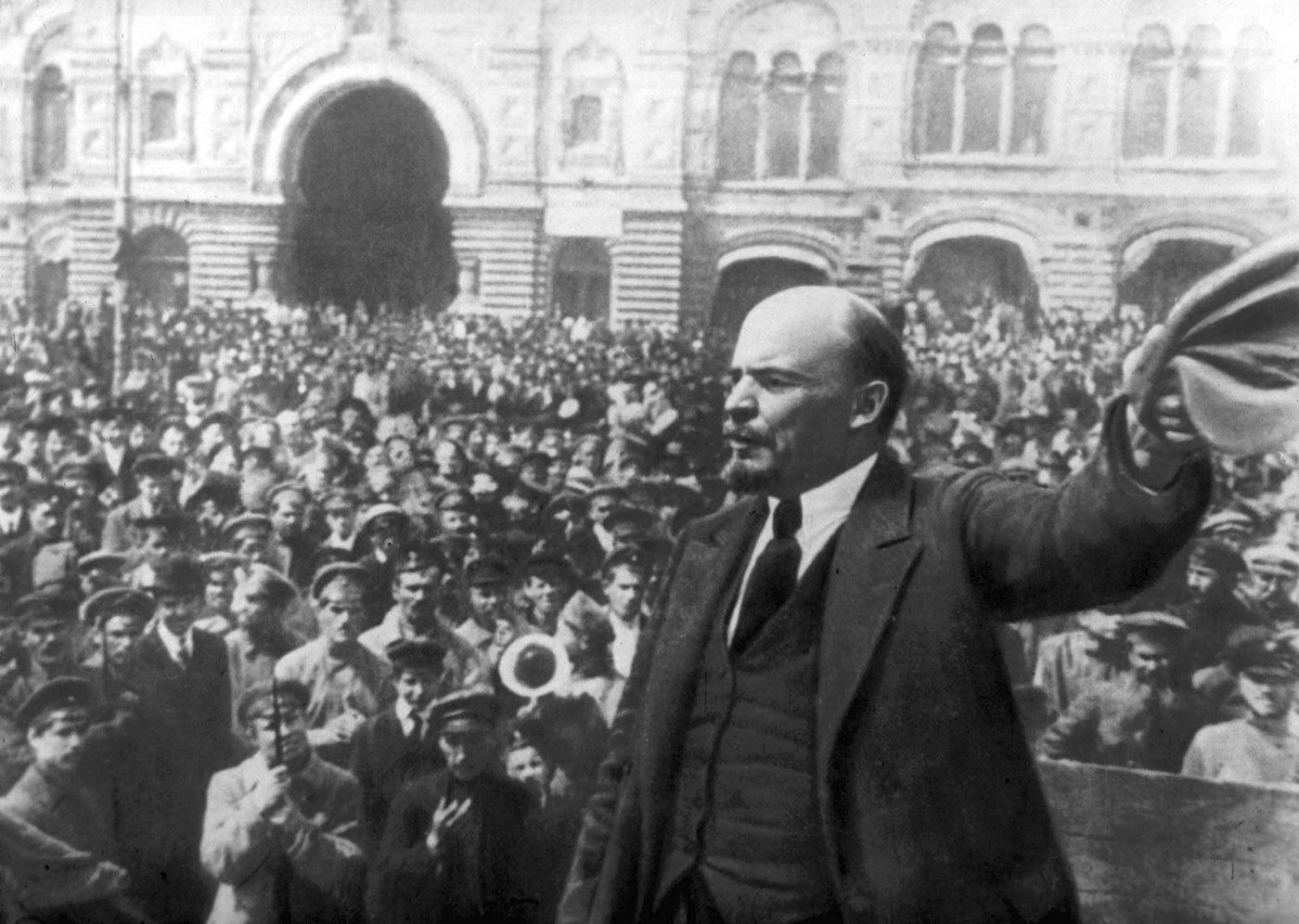

Psychoanalysis is like the Russian Revolution; we don’t know when it started going bad. (AO, 55)

Deleuze and Guattari compare psychoanalysis to the Russian Revolution to suggest that both began with revolutionary or transformative potential but eventually went awry. Again, psychoanalysis was not flawed from the start — something of value is present in its earlier stages. The Russian Revolution, particularly the Russian Revolution of 1917 which brought Vladimir Lenin’s Bolshevik party to power, began as a radical break from the exploitative system of capitalism, but ultimately led to authoritarianism and oppression under the Vanguard Party. And, after Lenin’s death, Joseph Stalin rose to power and implemented the policy of “Socialism in One Country,” that led to widespread oppression and the deaths of millions. Though Deleuze and Guattari are undoubtedly critical of exploitation under capitalism, they do not celebrate revolution uncritically. The difficult question must be raised: at what point did the revolution fail?

They continue questioning where psychoanalysis began to go astray:

We have to keep going back further. To the Americans? To the First International? To the secret Committee? (AO, 55)

- “To the Americans”: This seems to be a reference to Freudian thought spreading to America. One influential Austrian-born American psychiatrist is Abraham Brill who brought Freudian psychoanalysis to the America and translated Freud’s works. (Deleuze and Guattari might be commenting on how psychoanalysis may have changed when it entered America or even translation issues culminating in misinterpretations.)

- “To the First International”: This refers to the International Workingmen’s Association, a political international aimed at uniting a variety of left-leaning movements. There were a variety of internal divisions, such as a gender divisions (with women not initially allowed), and divisions between the statists and the anarchists. (Here, Deleuze and Guattari are deliberately talking about where the Russian Revolution may have gone awry.)

- “To the secret Committee”: This refers to a group of psychoanalysts in 1912 who were assigned to safeguard the direction and legacy of psychoanalysis. The Secret Committee sought to preserve Freud’s authority by countering the influence of Carl Jung and other different approaches.

Deleuze and Guattari continue with their questioning:

To the first ruptures, which signify renunciations by Freud as much as betrayals by those who break with him? (AO, 55)

They ask if psychoanalysis went awry when Freud denounced parts of his own works, such as his theoretical retreats allowing the possibility for Oedipus to slip in. They also posit that psychoanalysis went awry when theorists started to break from Freud (i.e., Carl Jung, Wilhelm Reich, etc.). They ask:

To Freud himself, from the moment of the “discovery” of Oedipus? (AO, 55)

Or perhaps the answer is deceptively simple: maybe everything went astray the moment Freud discovered Oedipus in his self-analysis.

Deleuze and Guattari write:

Oedipus is the idealist turning point. (AO, 55)

Regardless of its exact origins, Oedipus represents a conceptual shift. It is termed “idealist” because it imposes a universal framework of representation, contrasting with a materialist understanding of desire. This idealism lies in its reliance on interpretation, treating the unconscious as holistically representational. They state:

Yet it cannot be said that psychoanalysis set to work unaware of desiring-production. (AO, 55)

Once again, Deleuze and Guattari give credit where credit it due. Psychoanalysis is not at all unaware of the process of production:

The fundamental notions of the economy of desire — work and investment — keep their importance, but are subordinated to the forms of an expressive unconscious and no longer to the formations of the productive unconscious. (AO, 55)

Deleuze and Guattari emphasize the economy of desire using the concepts of work and investment (a clear tie to the political economy). Desire operates as a machinic process, creating connections, disjunctions, and so on, while also being invested into the social field. Although this conceptualization of desire retains its importance in psychoanalysis, desire becomes subordinated to representations. The unconscious is deemed “expressive” when it is treated as a classical theater instead of a factory.

They explain:

The anoedipal nature of desiring-production remains present, but it is fitted over the co-ordinates of Oedipus, which translate it into “pre-oedipal,” “para-oedipal,” “quasi-oedipal,” etc. (AO, 55)

When Deleuze and Guattari refer to the “anoedipal nature of desiring-production,” they mean that desiring-production is impersonal and not innately triangulated under and Oedipal schema. While this view of desire exists within psychoanalysis, it is always understood in relation to the Oedipal triangle, crushing the anoedipal nature of desire. For example, psychoanalysis attempts to acknowledge that there are phases considered ‘outside’ the Oedipal structure, but these are always interpreted in relation to Oedipus. Even pre-oedipal stages are already shaped by an Oedipal framework, having a structural relationship to Oedipus. Similarly, para-oedipal and quasi-oedipal phases appear peripheral, yet they are already oedipalized, since their existence depends on the central Oedipal structure.

As Deleuze and Guattari illustrate this with an example:

The desiring-machines are always there, but they no longer function except behind the consulting-room walls.

Behind the walls or in the wings, such is the place the primal fantasy concedes to desiring-machines, when it reduces everything to the Oedipal scene.

They continue nevertheless to make a hellish racket.

Even the psychoanalyst can’t ignore them. (AO, 55)

- There is an endnote after the phrase “Oedipal scene” that says:

On the existence of a little machine in the “primal fantasy,” an existence nevertheless always in the wings, see Sigmund Freud, “A Case of Paranoia Running Counter to the Psychoanalytic Theory of the Disease” (1915).

In A Case of Paranoia Running Counter to the Psychoanalytic Theory of the Disease, Freud analyzes a woman experiencing paranoid delusions. The patient tells Freud that she became sexually involved with a male coworker. Not long after their first sexual encounter, she sees him talking to an elderly female colleague at work. This triggers her first delusion: she begins to suspect that the man told personal details about their sexual relationship to the elderly woman, and as a result, she found the woman to start treating her differently. (Freud notes that this elderly woman is representative of the patient’s mother.)

Despite this, the women meets with the man for a second sexual encounter. During their sexual intercourse, she hears a clicking sound from across the room; she did not think much of the sound until she left his apartment and saw two men — one of them carrying what looks like a covered, box-like object. It is only then, retroactively, that the sound becomes significant to her: she convinces herself that someone had secretly taken photographs of her during the encounter, on behalf of the man’s order.

Freud interprets this as a paranoid delusion rather than literal surveillance. The “click” sound only takes on meaning after the encounter with the men outside. In fact, Freud states that there was no literal sound at all. Instead, he argues that the woman experienced a clitoral twitch during the sexual encounter — a somatic sensation that was then projected outwards and misrecognized as an external “click.” He links this projection to a “primal phantasy,” common to all neurotics: the fantasy of watching one’s parents having sex. However, the roles in this fantasy are reversed as the woman is no longer a child watching her parents having sex, but shifts to the position of the mother — and her lover being the father — with an imagined third party watching her. All elements in the story are read through Oedipus. The older woman stands in for the mother, the man the father, the woman herself taking the position of the mother, and the paranoid delusions rooted in oedipal relations.

Among the store of unconscious phantasies of all neurotics, and probably of all human beings, there is one which is seldom absent and which can be disclosed by analysis: this is the phantasy of watching sexual intercourse between the parents. I call such phantasies — of the observation of sexual intercourse between the parents, of seduction, of castration, and others — ‘primal phantasies’; and I shall discuss in detail elsewhere their origin and their relation to individual experience. The accidental noise was thus merely playing the part of a provoking factor which activated the typical phantasy of overhearing which is a component of the parental complex. (A Case of Paranoia Running Counter to the Psychoanalytic Theory of the Disease, 1915)

Though Deleuze and Guattari recognize Freud for glimpsing the desiring-machines in the case study, such as when he linked the auditory hallucination to a clitoral contraction. For, Deleuze and Guattari, these machinic process are always present — but remain “in the wings” in the context of psychoanalysis. The “little machine” that Deleuze and Guattari reference in the endnote, for example, likely references the clitorus-machine. Thus, even though Freud nearly identifies the machinic process, he ultimately reduces the desiring-machines to a familial drama.

When we analyze Deleuze and Guattari’s project more broadly, it is evident that when the analysand enters the consulting room and sits across from the analyst, the desiring-machines are already at work. However, the desiring-machines are pushed behind the walls and relegated to the Oedipal framework. The analyst interprets everything through the lens of primal fantasy — a pre-given narrative structure that is conceded to desiring-machines. This means that all desire is channeled through this primal fantasy, where everything is reduced to Oedipus. Desiring-machines do not disappear in this process as they are always functioning. Despite the analysts relentless attempt to interpret everything through Oedipus, the machines “make a hellish racket.”

[The psychoanalyst] tends therefore to maintain an attitude of denial: all of that is surely true, but it is still daddy-mommy. (AO, 55)

The psychoanalyst remains in denial. Even when psychoanalysts acknowledge the truth of desiring-machines and their productive nature, their analysis ultimately falls back on the same parental framework.

Deleuze and Guattari continue:

Over the consulting-room door is written, “Leave your desiring-machines at the door, give up your orphan and celibate machines, your tape recorder and your little bike, enter and allow yourself to be oedipalized.” (AO, 55–56)

- The mention of a “tape recorder” will be clarified in-depth within the upcoming sentences.

The desiring-machines only function behind the consulting-room walls because, prior to entry, the patient is met with a (symbolic) sign that prohibits them: a ban on orphaned, impersonal desiring-machines (a reference to the third synthesis), on tape recorders (potentially suggesting the second synthesis via the process of recording), and on bicycles (likely referencing the first synthesis, with the bicycle being present in Samuel Beckett’s works). Furthermore:

Everything follows from that, beginning with the unreliable character of the cure, its interminable and highly contractual nature, flows of speech in exchange for flows of money. (AO, 56)

Given the prior criticism of the psychoanalytic structural mode, it becomes evident that the so-called “cure” psychoanalysis offers is inherently unreliable. The process is endless, driven by an interpretive logic that reduces everything to Oedipus. It is also deeply contractual, shaped by bureaucratic routines and formalized exchanges: the patient speaks and pays money for the privilege. Psychoanalysis is a transactional, commodified practice.

Deleuze and Guattari write:

All that is needed is what is called a psychotic episode: after a schizophrenic flash, one day we bring our tape recorder into the analyst’s office — stop! — with this insertion of a desiring-machine everything is reversed: we have broken the contract, we are not faithful to the major principle of the exclusion of a third party, we have introduced a third element — the desiring-machine in person. (AO, 56)

- In the original French, it reads “a flash of schizophrenia” instead of “a schizophrenic flash.”

There is a footnote at the end of this sentence which states:

*Jean-Jacques Abrahams, “L’homme au magnetophone, dialogue psychanalytique,” Les Temps modernes, no. 274 (April 1969): “A: You see, it really isn’t so serious; I’m not your father, and I can still shout, of course not! There, that’s enough. — Dr. X: You are imitating your father at this moment? — A: Of course not, come off it, I’m imitating your father! The one I see in your eyes. — Dr. X: You are trying to take the role. . . . — A: . . . You can’t cure people, you can only palm off your father problems on them — problems you can’t get away from. And from session to session you drag along your victims that way with your father problem . . . .I was the sick one, you were the doctor. You’d finally reversed your childhood problem of being the child to your father. . . . — Dr. X: I was just telephoning extension 609 to make you leave — 609, the police, to have you thrown out. — A: The police? That’s it — Daddy! Your father’s a policeman! And you were going to call your father to come get me. . . . What insanity! You got all unnerved, excited, just because I brought out a little device that’ll let us understand what’s going on here.”

Deleuze and Guattari draw on the case of Belgian lawyer Jean-Jacques Abrahams — nicknamed “the man with the tape recorder” — as a real-world example. Abrahams published a piece titled L’homme au magnétophone, dialogue psychanalytique (The Man with the Tape Recorder, A Psychoanalytic Dialogue) in Les Temps modernes, the influential French journal founded by French existentialist Jean-Paul Sartre in 1945. This piece was published in 1969 and was later broadcast on the French cultural radio station, France Culture, in 1972.

Frustrated with the lack of progress in his psychoanalytic sessions, Abrahams brought a tape recorder into the consulting room. The transcript from this tape recorder reveals that “Doctor X” repeatedly tried to reduce Abraham’s desiring-machines to the Oedipal framework — everything, it seemed, came back to the father. Abrahams, using a satirical tone, suggested that it was perhaps the analyst who was projecting his father issues onto the patient. This interaction culminated in the doctor calling the police and having Abrahams involuntarily committed to Bruggman Hospital’s psychiatric ward. (I highly recommend reading the entire transcript.)

Deleuze and Guattari emphasize how a psychotic episode — “a flash of schizophrenia” — found in Abraham’s act of bringing a tape recorder into the analyst’s office, destabilizes the analyst-analysand relationship. This act fractures the implicit contractual obligation of psychoanalysis: the private exchange between analyst and analysand that strictly excludes any third party. The desiring-machine is directly inserted into the clinical setting — the desiring-machine in person destabilizes the supposed sanctity of the analyst’s office.

Deleuze and Guattari write:

Yet every psychoanalyst should know that, underneath Oedipus, through Oedipus, behind Oedipus, [the psychoanalysts’] business is with desiring-machines. (AO, 56)

They explain that even if psychoanalysts keep Oedipus at the forefront, they should be fully aware that they are working with desiring-machines:

At the beginning, psychoanalysts could not be unaware of the forcing employed to introduce Oedipus, to inject it into the unconscious. (AO, 56)

Throughout this section, it has been evident that Deleuze and Guattari praise Freud’s early discoveries. Freud, in his early stages, was careful to not inject Oedipus into the unconscious. However, something dangerous happened:

Then Oedipus fell back on and appropriated desiring-production as if all the productive forces emanated from Oedipus itself. (AO, 56)