Each preceding section has focused on the three syntheses of the unconscious. As seen in Chapter 1.5, the three syntheses were summarized, providing a structured view of the process of production. Now that this process has been outlined through these three modes, it is essential to examine how the whole that emerges from the production process subsequently falls back on and influences the production process itself.

Note 1: I will constantly be revising this blog post in order to do a line-by-line interpretation of the text.

- Citation Note: Full citation provided at the end of this post

Paragraph One

Deleuze and Guattari being this section by speaking of desiring-machines:

In desiring-machines everything functions at the same time, but amid hiatuses and ruptures, breakdowns and failures, stalling and short circuits, distances and fragmentations, within a sum that never succeeds in bringing its various parts together so as to form a whole. (AO, 42)

Desiring-machines operate by breaking down, with specific kinds of breaks found within each synthesis. However, desiring-machines never coalesce into a totality. They do not form a unified whole in the sense of integrating all partial objects into a unified, cohesive whole. (We will soon learn that the whole serves as a part among parts). Deleuze and Guattari continue:

That is because the breaks in the process are productive, and are reassemblies in and of themselves. (AO, 42)

Due to the productive nature of the breaks in each synthesis, this defines the process of production as having a productive nature. This process is defined by a continuous state of rearrangement with no whole being produced (in the sense of a unified totality). To highlight this continuous process, Deleuze and Guattari explain that the second and third syntheses allow for infinite permutations and becomings, making the concept of a unified whole untenable:

Disjunctions, by the very fact that they are disjunctions, are inclusive.

Even consumptions are transitions, processes of becoming, and returns.

(AO, 42)

The question, then, becomes how the whole is conceptualized in relation to desiring-machines. Deleuze and Guattari write:

Maurice Blanchot has found a way to pose the problem in the most rigorous terms, at the level of the literary machine: how to produce, how to think about fragments whose sole relationship is sheer difference — fragments that are related to one another only in that each of them is different — without having recourse either to any sort of original totality (not even one that has been lost), or to a subsequent totality that may not yet have come about? (AO, 42)

In this quote, Deleuze and Guattari reference French writer and literary theorist Maurice Blanchot’s The Infinite Conversation, published in 1969. The text consists of multiple interwoven texts and dialogues that remain open-ended, without reaching a final conclusion or culmination. Throughout the book, Blanchot references Heraclitus’ Fragments which Deleuze and Guattari might be alluding to. However, Deleuze and Guattari specifically reference pages 451–452 of The Infinite Conversation. (I am working on getting a copy of the French text; all we know is that each fragment of the text relates to the others only through difference.) When connecting The Infinite Conversation to desiring-machines, we see that fragments and partial objects neither originate from a prior totality nor operate teleologically towards a fixed end or finality.

They continue:

It is only the category of multiplicity, used as a substantive and going beyond both the One and the many, beyond the predicative relation of the One and the many, that can account for desiring-production: desiring-production is pure multiplicity, that is to say, an affirmation that is irreducible to any sort of unity. (AO, 42)

At this juncture, this section’s title becomes evident: we are engaging with the concept of the One and the Many, which Deleuze and Guattari reconfigure beyond its normative understanding. To grasp their reconceptualization, is is necessary to first examine the concept of the One and the many and then interpret the quote:

The One and the many is a metaphysical problem concerned with unity and plurality. Simply put, this problem questions the nature of reality by asking whether the material world, composed of various parts (the many), is ultimately grounded in a singular totality (the One). Further still, this concept examines how unity and plurality relate:

- Is the One separate from and superior to the many, forming a hierarchical structure?

- Is the many derived from the One, or do they exist in a reciprocal relationship?

- If God is the One, then did God create the many? Or does the many emanate from God?

- Can the distinction between the One and the many itself be challenged?

The concept of the One and the Many traces back to the ancient Greeks in Western philosophy, with its significance emphasized in Platonism and Neoplatonism. However, this idea also appears in Thomistic metaphysics, where God creates nature from nothing. Additionally, Descartes and Spinoza engage with this question through substance dualism (Cartesian dualism) and substance monism, respectively. In contrast to monism, Leibniz and Whitehead further explore variations of pluralism — Leibniz through idealist pluralism and Whitehead through dynamic pluralism.

- Note: I am strictly discussing the Western philosophical tradition here. Eastern philosophy has engaged the concept of the One and the many long before the West, but I am not well-read enough in the Eastern tradition to discuss it in-depth.

Once we get a decent grasp on this concept, it becomes clear why Deleuze and Guattari redefine the relationship between the One and the many, diverging from some thinkers while expanding upon others. Deleuze and Guattari state in A Thousand Plateaus, “PLURALISM = MONISM.” However, their conceptualization of pluralism being equal to monism has its roots in their conceptualization of “the whole and its parts” explained in this section of Anti-Oedipus.

For now, I will briefly explain the philosophical perspectives listed (I will eventually create a blog post explaining these various perspectives in-depth):

Platonism

In Platonism, Plato privileges the One over the many, viewing the world of Forms as a perfect unity or totality (the One) in contrast to the imperfect, material world (the many). Plato’s Republic serves as key text for understanding this concept, particularly through the theory of Forms in relation to justice and goodness. Within this framework, a strict division exists between the metaphysical and the physical, the perfect and the imperfect — with the Form of Good positioned at the top of the hierarchy, guiding everything beneath it. While Book I of Plato’s Republic dives into this concept (my blog on this can be found here), Book VI is well-known for its explanation of this concept via the allegory of the cave. In the following quote, Plato discusses how the prisoners eventually escape the cave and experience the true, universal nature of reality (the One):

Last of all, he would be able to look at the Sun and contemplate its nature, not as it appears when reflected in water or any alien medium, but as it is in itself in its own domain. (The Republic of Plato; Book VI)

**Quick shoutout: Aristotle deserves mention here as his metaphysics won’t be explained in this post. While he does not belong to the school of Platonism or Neoplatonism, he does engage with the concept of the One and the many. His work became foundational for various Neoplatonists who built upon his ideas.

Neoplatonism

In Neoplatonism — with Plotinus as its credited founder (his name notably resembling Plato’s) — we see a shift from the Platonist framework. For Plotinus, the many emanates from the One rather than existing in contrast to it. In Plotinus’ text On Beauty within the Enneads, he explains that the conceptualization of beauty, for example, does not necessitate the reduction of parts to a transcendent, opposed One — the true Form of Beauty — but instead acknowledges that beauty cannot be divorced from the parts that compose it. Per the Neoplatonist tradition, there is no lost totality, but rather a totality that each part participates in. The One is not divorced from the many — it organizes the many. Plotinus writes:

The form, then, approaches and composes that which is to come into being from many parts into a single ordered whole; it brings it into a completed unity and makes it one by agreement of its parts; for since it is one itself, that which is shaped by it must also be one as far as a thing can be which is composed of many parts. (Enneads; On Beauty)

Thomism

In Thomistic metaphysics, Thomas Aquinas privileges the One over the many. In his Summa Theologica, unfinished at his death in 1274, Aquinas outlines the ‘Five Ways’— five arguments demonstrating the existence of God. Without delving into the specifics of these arguments, what is crucial to note is Aquinas’ alignment with the broader Christian tradition in affirming creation ex nihilo — that is, creation from nothing. In this view, God exists outside of nature as both its cause and end.

There is no case known (neither is it, indeed, possible) in which a thing is found to be the efficient cause of itself; for so it would be prior to itself, which is impossible … Therefore it is necessary to admit a first efficient cause, to which everyone gives the name of God.

(Summa Theologica; Part I)

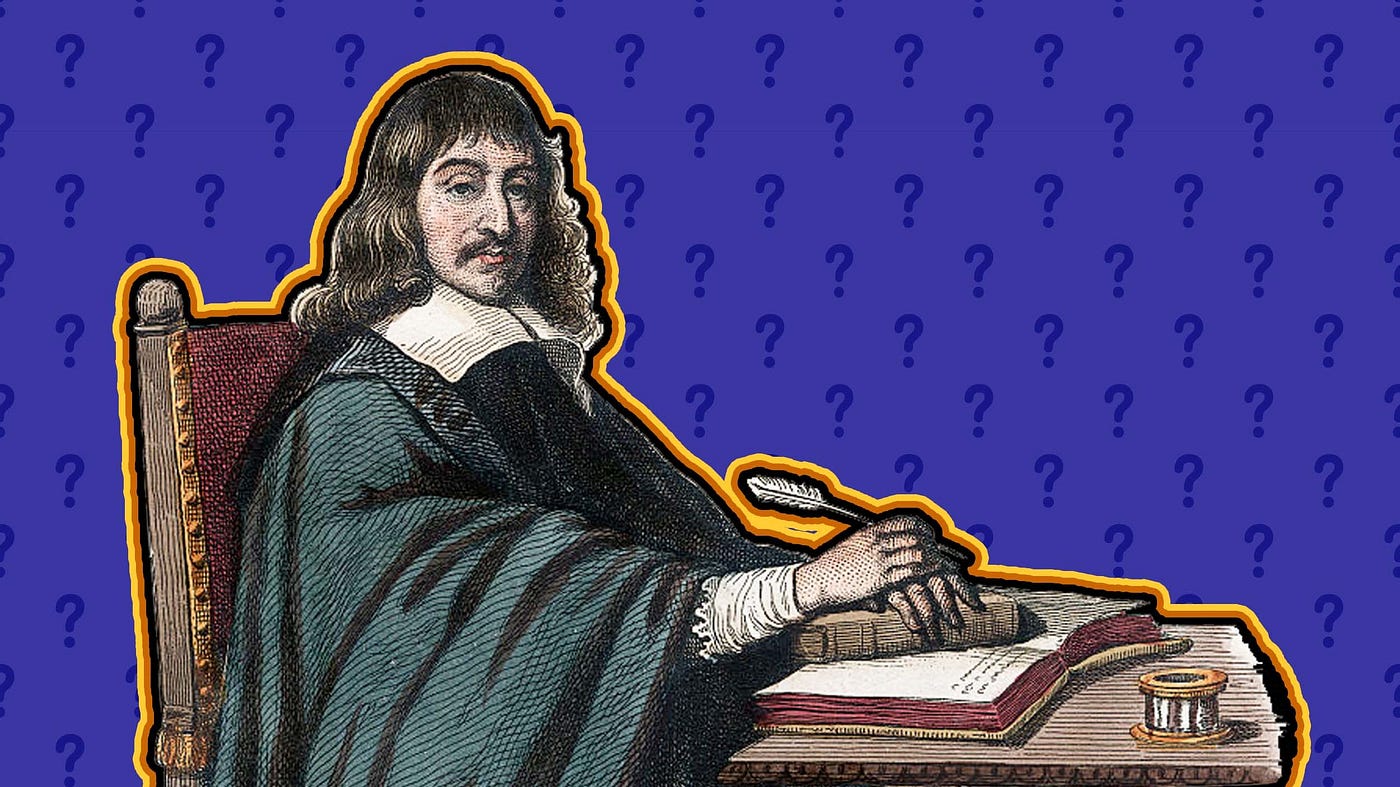

Substance Dualism (Cartesian Dualism)

Though substance dualism is not explicitly framed in relation to the One and the many, I find it important to include in this discussion.

In Cartesianism, René Descartes questions whether a subject can truly know if they are dreaming. He argues that our senses might deceive us, leading him to doubt the reliability of matter. He even considers the possibility of being deceived by an evil demon that manipulates perception. Despite this, Descartes concludes that even if he cannot prove whether he is dreaming or being deceived, he can still think. This leads to his famous conclusion: “Cogito, ergo sum” — “I think, therefore I am.” For Descartes, the act of thinking implies the existence of a thinking subject. (Descartes privileges mind over matter.)

From here, he builds arguments for the existence of God, establishing a metaphysical hierarchy. While Descartes does not explicitly frame his philosophy in terms of the One and the many, his system aligns with the concept — where God functions as the One, and all contingent beings (including the thinking subject) fall under the many.

I am therefore … only a thinking thing … I am therefore a true thing, and one that truly exists; but what kind of thing? I have said it already: one that thinks. (Meditations on First Philosophy; Second Meditation)

My blog post on Descartes can be found here.

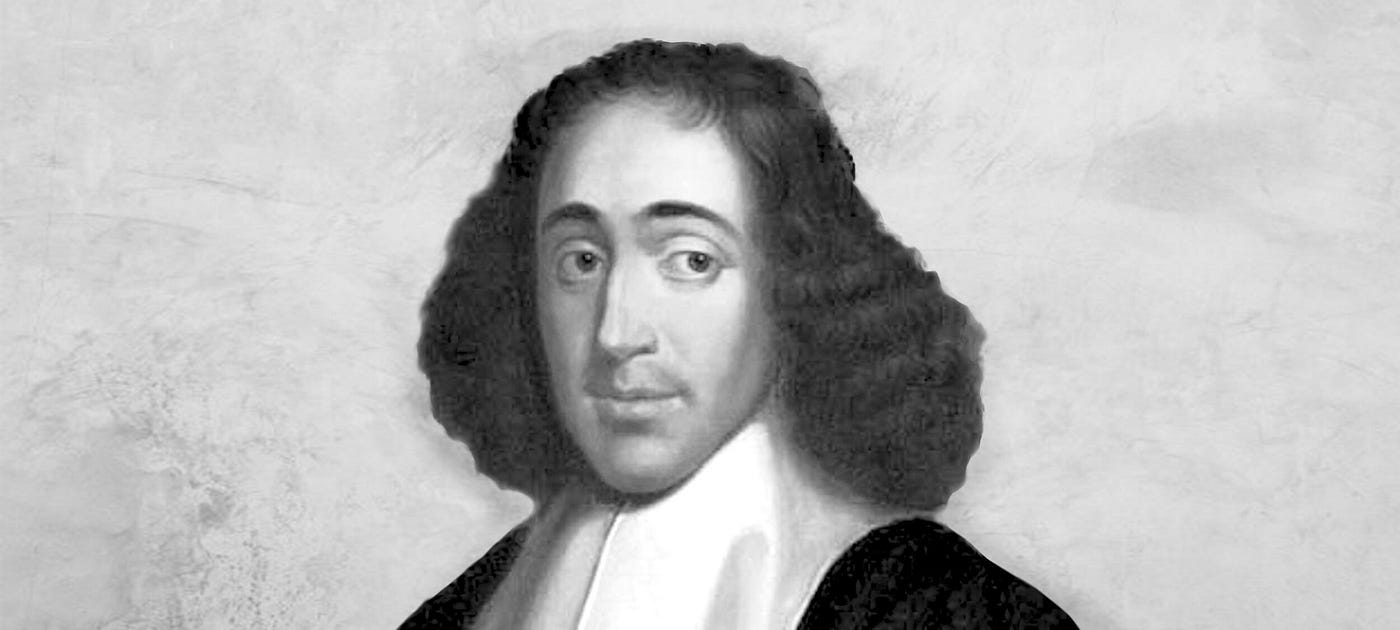

Substance Monism

In substance monism, there is only one eternal and unchanging fundamental substance with this substance being the cause of itself. Baruch Spinoza is an important figure that Deleuze and Guattari draw upon heavily, so his substance monism will be explained here. Spinoza argues for a one-substance model, claiming that God and Nature are fundamentally identical. This substance (which he calls “God” and “Nature” synonymously) possesses infinite attributes, each of which expresses the essence of the substance in different ways. This allows Spinoza to argue that there is individuation within this his view of monism, unlike the strict substance monism of others such as the ancient Greek philosopher Parmenides, who argues that change and individuation are illusions, with ‘Being’ as the ultimate, unchanging totality. My blog post on Parmenides’ Being can be found here.

Spinoza acknowledges, however, that humans can only conceptualize two attributes of this substance: thought and extension. Additionally, Spinoza discusses “modes,” which are finite expressions of the one substance — such as the individual mind or body. While these modes are individuates and particular, they are still dependent upon the one substance.

For Spinoza, God is completely immanent as there is no distinction between God and Nature. Through various definitions, axioms, and propositions in Part I of Ethics, Spinoza presents an extremely compelling and ultimately enjoyable argument for pantheism.

PROP. V. There cannot exist in the universe two or more substances having the same nature or attribute. (Ethics; Part I)

Idealist Pluralism

In “idealist pluralism” (as it might be termed), there are infinite substances, each of which has its own unique individuality. Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz examines the nature of matter and argue that when a compound is repeatedly broken up or divided, it eventually reaches a point where it no longer consists of material particles but instead consists of immaterial, simple substances. He calls these simple substances monads. Leibniz argues that there are an infinite number of monads, each of which is unique and indivisible.

Each monad is windowless, meaning that is does not interact or have an effect on other monads. The concept of a “windowless” monad highlights that the internal state of a monad does not depend on any external influence; it is determined by its own nature. For example, the transfer of heat — as we normally understand it — is the movement of heat from one object to another. However, Leibniz finds this problematic as, if this were the case, there would be an infinitesimally small moment where heat exists independently between objects, which he deems absurd.

Therefore, Leibniz explains that each monad is qualitatively changing due to its individual nature. For instance, when considering the heat example, one monad’s internal state might change from having a quality of heat to not having it, which another monad’s internal state might change from not having heat to having it. This change happens in accordance to a “pre-established harmony” created by God — the supreme monad. In this way, God’s pre-established harmony has set up the universe so that all monads, without interacting with one another, operate in a perfect synchronization.

In contrast to substance monism, Leibniz argues for a type of ideal pluralism — the existence of infinite substances which exist in perfect harmonization. For Leibniz, God is both transcendent and immanent as God is beyond the created world and immanent to the coordinated activities of all monads.

My blog post on Leibniz’s monad can be found here.

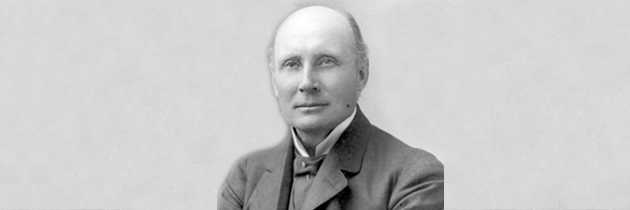

Dynamic Pluralism

In “dynamic pluralism” (as it might be termed), there is a rejection of substance metaphysics altogether. Alfred North Whitehead can be credited as an essential thinker of this kind of dynamic pluralism where reality is conceptualized as always changing, defined and produced by interrelated processes, events, and occasions. Rather than a universal substance, Whitehead conceives reality as a network of “actual occasions” (also known as “actual entities”) — momentary events of becoming — that continuously interact, build upon the past and contribute to future events.

Whitehead’s metaphysics is developed in response to substance metaphysics in general, and, to an extent, a response to Spinoza in particular. He criticizes Spinoza’s conceptualization of substance as the ultimate grade of reality (“most ultimate characterization of fact”) as Spinoza treats substance as an unchanging foundation that all modes depend upon. Whitehead rejects the idea that modes must relate to or derive from such a “higher reality.” For Whitehead, the actual entities themselves are the building blocks of existence and constitute reality through their interactions.

Therefore, Whitehead rejects substance metaphysics in favor of process philosophy. His philosophy of the organism posits that reality is not made up of static substances, but of processes or actual entities (events or occasions). Instead of adhering to the normative notions of being (which contain a static essence), Whitehead emphasizes becoming — a dynamic process of events unfolding.

The philosophy of organism is closely allied to Spinoza’s scheme of thought. But it differs by the abandonment of the subject-predicate forms of thought, so far as concerns the presupposition that this form is a direct embodiment of the most ultimate characterization of fact. The result is that the ‘substance-quality’ concept is avoided; and that morphological description is replaced by description of dynamic process … It does not lead us to the discovery of any higher grade of reality. The coherence, which the system seeks to preserve, is the discovery that the process, or concrescence, of anyone actual entity involves the other actual entities among its components.

(Process and Philosophy; Chapter I; emphasis mine)

Pluralism = Monism

Though Deleuze and Guattari do not directly discuss each of the philosophies listed above, having a rudimentary understanding of the various types of metaphysics can help us understand their metaphysics.

Referring back to where we last left off in Anti-Oedipus, it is evident that the concept of multiplicity is treated as a noun (though Deleuze and Guattari use the term “substantive” which is a largely obsolete term). The concept of multiplicity goes beyond the dichotomous relationship between the One and the many, which is structured by a predicative relation. A predicate is what defines the subject in a statement. For example the predicates are bolded:

- The One is in opposition to the many. (Platonism)

- The many emanate from the One. (Neoplatonism)

In the case of the One and the many, their meanings are interdependent, meaning that one is only understood in relation to the other. This is what Deleuze and Guattari reject; instead of conceptualizing the One and the many as mutually defined opposites, they propose multiplicity as a concept that exists beyond this binarization. As we have previously examined the three syntheses, the process of desiring-production cannot be reduced to a unity or totality: it is a process.

Therefore, Deleuze and Guattari are using elements from monism and pluralism to craft their metaphysics. In later paragraphs, they will describe their metaphysics more clearly.

Paragraph Two

The second paragraph opens with Deleuze and Guattari’s argument made in the preceding paragraph:

We live today in the age of partial objects, bricks that have been shattered to bits, and leftovers. (AO, 42)

Rather than presupposing a totality, Deleuze and Guattari emphasize the presence of various breaks within each synthesis. Their reference to “partial objects,” “bricks,” and “leftovers” parallels the three syntheses, highlighting that none of them assume a unified whole. Instead, each synthesis exhibits some kind of disconnection, detachment, or residue — none of which should be mistaken for lack or deficiency. Furthermore:

We no longer believe in the myth of the existence of fragments that, like pieces of an antique statue, are merely waiting for the last one to be turned up, so that they may all be glued back together to create a unity that is precisely the same as the original unity. (AO, 42)

The example of a statue serves as an apt illustration. When viewed from the perspective of the fragment, it is tempting to assume that these pieces belong to a greater whole, leading one to endlessly search for a missing piece that would restore a sense of totality (the One). Similarly, if one begins with the One as a totality or considers each part solely in relation to that totality, the same trap is set. This analysis can be summed up as follows:

We no longer believe in a primordial totality that once existed, or in a final totality that awaits us at some future date. (AO, 42)

The whole was never something that pre-existed or exists as some lost object to be attained in the future.

Deleuze and Guattari continue:

We no longer believe in the dull gray outlines of a dreary, colorless dialectic of evolution, aimed at forming a harmonious whole out of heterogeneous bits by rounding off their rough edges. (AO, 42)

The critique presented here challenges the teleological framing of evolution as progressing toward a finality or harmonious whole. It specifically criticizes the idea that heterogeneous elements can be seamlessly shaped to fit together, like pieces of a puzzle in order to achieve wholeness. None of this is to assume that Deleuze and Guattari refuse to believe in totalities:

We believe only in totalities that are peripheral. (AO, 42)

The totality that Deleuze and Guattari find legitimacy exists on the periphery — produced alongside parts while falling back on the production process. Further still:

And if we discover such a totality alongside various separate parts, it is a whole of these particular parts but does not totalize them; it is a unity of all of these particular parts but does not unify them; rather, it is added to them as a new part fabricated separately. (AO, 42)

Deleuze and Guattari emphasize that this “totality” functions as a whole that refuses to totalize its parts; it does not unify parts within a transcendent wholeness. Instead, this newfound totality is produced in a way that is innately integrated into the production process. This aligns with the opening pages of Anti-Oedipus, where Deleuze and Guattari reject the creator/creation relationship, proposing instead a producing/product relationship. The product is the producer; the producer is the product. The distinction between the production process and the product is indistinct.

Paragraph Three

Deleuze and Guattari continue:

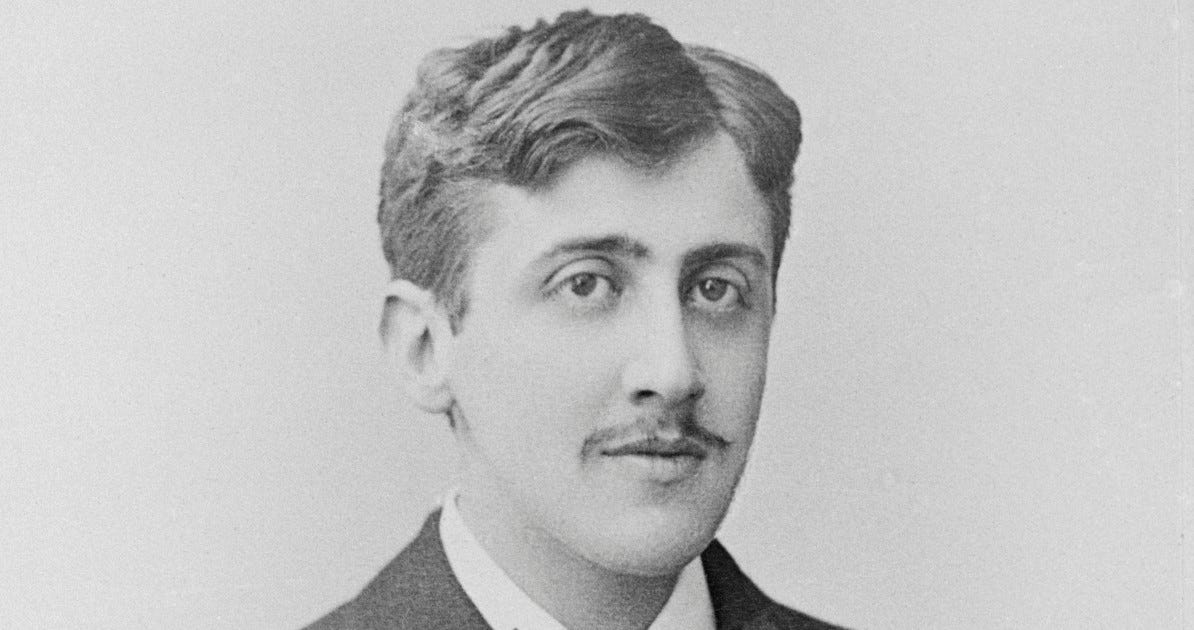

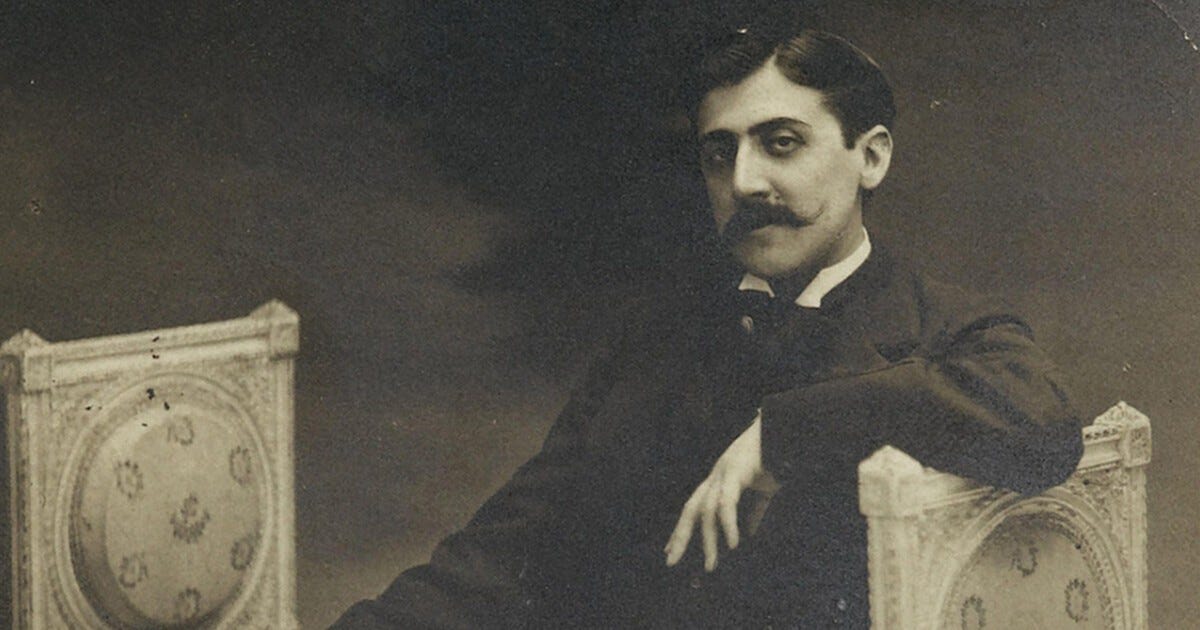

“It comes into being, but applying this time to the whole as some inspired fragment composed separately. . . .” So Proust writes of the unity of Balzac’s creation, though his remark is also an apt description of his own oeuvre. (AO, 42)

In this sentence, Deleuze and Guattari cite French novelist Marcel Proust’s analysis of Honoré de Balzac — specifically Proust’s book In Search of Lost Time published in 1913. An endnote follows this sentence, where the translators note that the title In Search of Lost Time “stresses the notion of search and voyage.” Regardless, Proust praises his fellow French novelist Balzac by identifying a form of unity in his works — but not through the unification of fragments (it is a unity that does not unify). Instead, Proust sees the whole in Balzac’s works as inspired by a separately composed fragment. Yet, Deleuze and Guattari find that Proust’s description of Balzac’s work can be applied to his own oeuvre.

They write (a very long sentence):

In the literary machine that Proust’s In Search of Lost Time constitutes, we are struck by the fact that all the parts are produced as asymmetrical sections, paths that suddenly come to an end, hermetically sealed boxes, noncommunicating vessels, watertight compartments, in which there are gaps even between things that are contiguous, gaps that are affirmations, pieces of a puzzle belonging not to any one puzzle but to many, pieces assembled by forcing them into a certain place where they may or may not belong, their unmatched edges violently bent out of shape, forcibly made to fit together, to interlock, with a number of pieces always left over.

(AO, 42–43)

Rather than reading all seven volumes of In Search of Lost Time, I chose to read Patrick Alexander’s Marcel Proust’s Search for Lost Time: A Reader’s Guide to The Remembrance of Things Past. I highly recommend reading Part I of this guide as it provides a concise synopsis of each book (and it is only eight pages). When reading through the guide, it becomes evident that In Search of Lost Time is a novel of fragmentation. It takes the form of a fictional autobiography, with a protagonist whose life closely mirrors Proust’s own life. Alexander notes that the story is told through two distinct voices — the narrator as a young boy and as an older man reflecting his youth. This narrative structure, with its shifting timeline and frequent digressions, along with themes relating to sexuality, relationships, family life, and so on, makes the novel fragmented.

In the quote above, Deleuze and Guattari describe In Search of Lost Time as a literary machine in which all parts are asymmetrical — some following paths that abruptly stop, others sealed in airtight (hermetically sealed) boxes, or in a container that is closed off and not communicative with the outside world. Further still, gaps exist between parts that are “contiguous,” meaning that gaps exist between parts that are directly adjacent. However, these gaps are not defined by negation or lack — they are defined in terms of abundance or affirmation.

Deleuze and Guattari reject the notion of uncovering a final fragment that would serve as the key to totality, like a puzzle piece that completes a single, universal puzzle. If the parts are conceptualized as puzzle pieces, they must be conceived of as pieces that belong to a multitude of puzzles, where pieces have no fixed place. A piece is assembled by being forces into various places and spaces — it might fit neatly or not, but there is no transcendent puzzle where each piece fits in a predetermined space. These pieces have “unmatched edges,” requiring them to be forced together with all kinds of other pieces.

The most interesting part of this quote is towards the very end, where Deleuze and Guattari write that “a number of pieces is always left over.” There is no missing piece that can be construed in terms of lack, but rather, there are pieces left over that can be understood in terms of abundance. With left over pieces, there is infinite potentiality for connections and disconnections, attachments and detachments, as an energy or residue left behind in each movement.

To continue:

[In Search of Lost Time] is a schizoid work par excellence: it is almost as though the author’s guilt, his confessions of guilt are merely a sort of joke. (AO, 43)

In Search of Lost Time follows a narrator who drifts through a vast array of memories, with the narrative unfolding in a non-linear manner. Deleuze and Guattari define it as a “schizoid work,” emphasizing its fragmentation and refusal of a totalizing interpretation. Various parts of the text can be rearranged in different ways, allowing for multiple interpretations.

Deleuze and Guattari discuss Proust’s expressions of guilt in the text, possibly alluding to Proust’s identity as a half-Jewish man and (possibly) closeted homosexual showing in his writing. For example, Baron de Charlus, a character in the novel, is a closeted gay man who has secret homosexual relationships, yet is openly flamboyant. Or, this expression of guilt could just as easily be the narrator’s obsessive attempt to uncover the sexuality of his partner, Albertine Simonet, whom he suspects of having had lesbian relationships. Even then, Deleuze and Guattari could be referencing something unrelated to sexuality as there is a specific passage within In Search of Lost Time where the narrator experiences guilt while looking at a photograph of his deceased grandmother. In this moment, he recalls drinking alcohol in front of her, despite her disapproval. This memory then leads to another recollection — his grandfather drinking alcohol in front of his grandmother, prompting an upset reaction from the grandmother which others found amusing. Thus, these expressions of guilt comes off as amusing or “merely a sort of joke.”

When referring to Proust’s “schizoid work par excellence” with various confessions of guilt present, Deleuze and Guattari write:

(In Kleinian terms, it might be said that the depressive position is only a cover-up for a more deeply rooted schizoid attitude.) (AO, 43)

When Deleuze and Guattari speak of “Kleinian terms,” they are referring to the perspectives of Melanie Klein, an American-British psychoanalyst whose work they engage with throughout Anti-Oedipus. (Later in this section, Klein’s ‘discovery’ of partial objects will become more prominent.) The terms “depressive position” and “schizoid attitude,” as referenced by Deleuze and Guattari, originate from Melanie Klein’s Notes on Some Schizoid Mechanisms (1946).

My blog post on Notes on Some Schizoid Mechanisms can be found here.

In this text, Klein discusses the subject during the first three months of infancy:

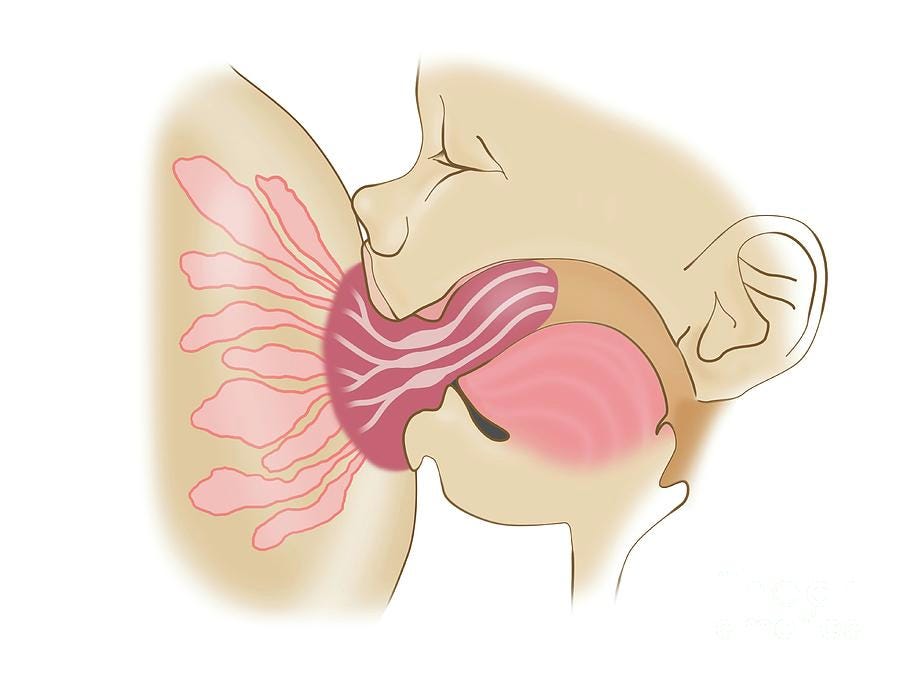

- The paranoid-schizoid position is characterized by fragmentation. In the first three months of infancy, the infant does not experience objects as cohesive wholes but rather as partial objects that are perceived as entirely good or entirely bad. This stage is driven by attraction and persecution — the infant feels attached to the “good” object while experiencing the “bad” object as a source of distress and threat. For example, the mother’s breast is perceived as “good” when it satisfies hunger but as “bad” or persecutory when it fails to do so. This persecutory experience is influenced by the death instinct, which Klein sees as an innate force in the subject which causes anxiety due to fear of annihilation (death). In response, the infant projects aggression outward, leading to destructive behaviors such as biting the mother’s nipple.

- The depressive position refers to the shift from fragmentation to integration. In this stage, the infant begins to recognize that previously fragmented perceptions of objects — such as the “good breast” and “bad breast” — actually belong to a single, whole object — the mother. This realization brings about guilt and concern, as the subject understands that their attempts to destroy the object by biting the nipple or hitting the breast, is also an attempt to destroy something beneficial.

Later, I will provide a more in-depth analysis of Klein’s work. For now, it is only necessary to grasp the general concept of how psychoanalysts might apply her theories to Proust’s experience of guilt. When reading Proust through a Kleinian lens, it becomes evident that these cohesive feelings of guilt function as a mere cover for the underlying schizoid attitude — the fragmentation that defines In Search of Lost Time.

They continue by discussing the concept of the One and the many:

For the rigors of the law are only an apparent expression of the protest of the One, whereas their real object is the absolution of fragmented universes, in which the law never unites anything in a single Whole, but on the contrary measures and maps out the divergences, the dispersions, the exploding into fragments of something that is innocent precisely because its source is madness. (AO, 43)

Deleuze and Guattari explain that the “rigors of the law,” or the way that law is normatively understood, are merely an apparent expression of the One. This means that when we consider holistic frameworks like natural law or general metaphysical traditions — where law is rooted in a unified, overarching principle such as divine morality or causal necessity — we are interpreting law in a conventional context that presupposes a strict unification. But this is only apparent.

In reality, the law has its real object as the “absolution of fragmented universes.” Rather than uniting and totalizing parts into a single Whole, the law is continuously embracing fragmentation and parts that never fit neatly into a totalizing whole. Deleuze and Guattari describe this as something innocent due to its source being one of madness —

Deleuze and Guattari apply this analysis of the Whole and its parts to Proust’s literary work:

This is why in Proust’s work the apparent theme of guilt is tightly interwoven with a completely different theme totally contradicting it; the plantlike innocence that results from the total compartmentalization of the sexes, both in Charlus’s encounters and in Albertine’s slumber, where flowers blossom in profusion and the utter innocence of madness is revealed, whether it be the patent madness of Charlus or the supposed madness of Albertine. (AO, 43)

It is evident that In Search of Lost Time contains various themes, one of which is guilt, mentioned above. However, this theme is “tightly interwoven” with another: the theme of sexual identity and expression. The “compartmentalization of the sexes” refers to how Proust portrays sexuality as something that resists an innate totalization.

In the case of Charlus, mentioned in the quote, we find an individual who neither openly declares his homosexuality nor denies it. Living in an anti-queer society, Charlus exercises discretion about whom he confides in and has sexual relations with, frequenting secretive spaces. Yet, at the same time, he displays flamboyance, making his homosexuality appear obvious to those who are perceptive. And, in the case of Albertine, her ‘sleep’ — a metaphor for her unknowable and elusive sexual identity — showcases the impossibility of neatly categorizing her sexuality within a predefined framework. Even the narrator notes her potential lesbianism but has no way of confirming it. Deleuze and Guattari’s reference to flowers blossoming suggests an innocence associated with this fragmentation of sexuality exhibited by Charlus and Simonet. Here, innocence does not imply morality, but rather, a kind of existence beyond conventional judgment (a judgment that is always in relation to the Whole).

- The “patent madness of Charlus” refers to the undeniable expression of his sexuality — a madness that is open for all to witness.

- The “supposed madness of Albertine” refers to the projection of madness onto her, as her sexuality remains unconfirmed by the narrator.

Paragraph Four

As this section has explored the metaphysical question of the One and the many — with Deleuze and Guattari reframing it in terms of the Whole and its parts — they now move on to articulate their metaphysical framework:

Hence Proust maintained that the Whole itself is a product, produced as nothing more than a part alongside other parts, which it neither unifies nor totalizes, though it has an effect on these other parts simply because it establishes aberrant paths of communication between noncommunicating vessels, transverse unities between elements that retain all their differences within their own particular boundaries.

(AO, 43)

This is their metaphysics: the whole is produced as a part alongside other parts. There is no difference between the One and the many. The whole does not unify or totalize the parts that it is produced alongside. However, none of this means that the whole has no effect on the parts; the whole “establishes aberrant paths of communication” between parts that are not in direct communication with one another (“noncommunicating vessels”). The whole that is produced as just another part serves to “transverse unities,” indicating that particular elements of parts retain their difference while being linked to other parts. Deleuze and Guattari continue:

Thus in the trip on the train in In Search of Lost Time, there is never a totality of what is seen nor a unity of the points of view, except along the transversal that the frantic passenger traces from one window to the other, “in order to draw together, in order to reweave intermittent and opposite fragments.” (AO, 43)

The train trip serves as a metaphor for the perception of fragmentation and totalization. The passenger moves frantically from one window to another, attempting to piece together a holistic, unified view of the outside world. However, this shifting perspective never forms a complete totality, as no singular, unified viewpoint emerges. Instead, the act of traversing the train connects various fragments — different windows and rooms of the train— without being integrated into a seamless whole. Therefore, the whole is not something that pre-exists or something that awaits the passenger at a later date; the whole is produced alongside a fragmented parts that link together in such a way that still retains their differences.

They write:

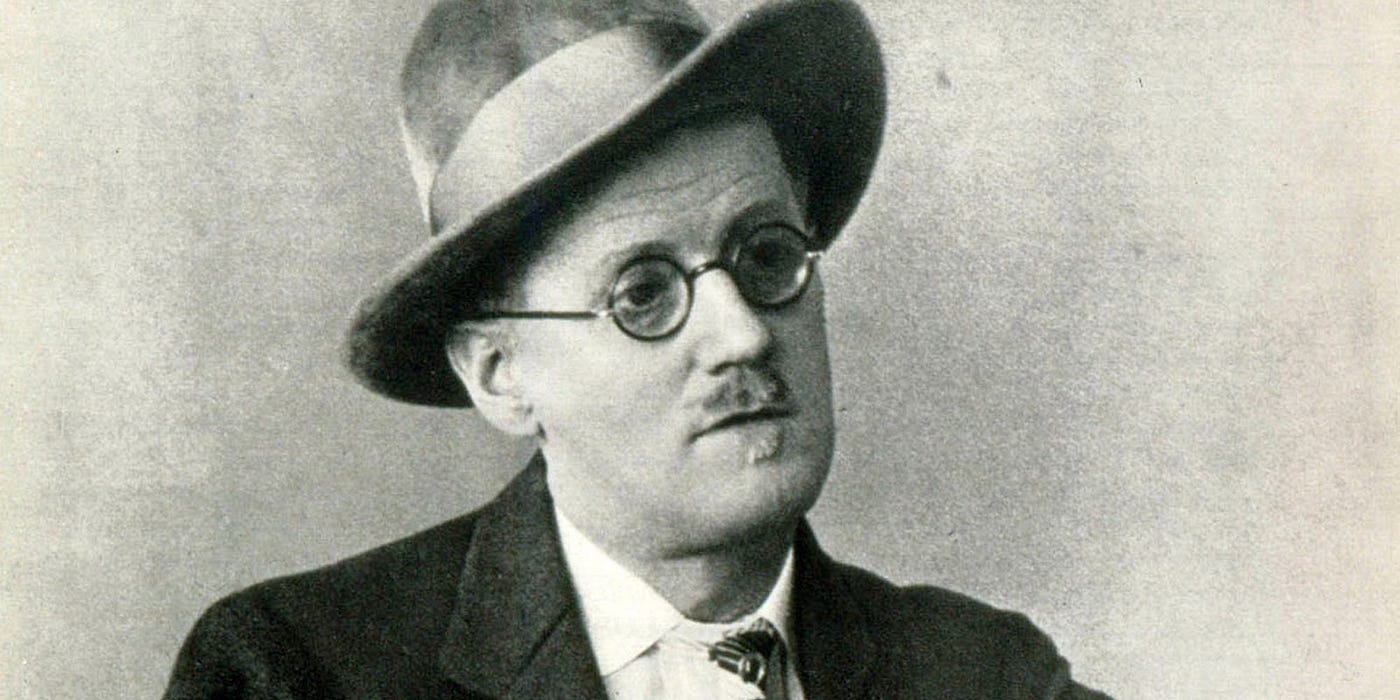

This drawing together, this reweaving is what Joyce called re-embodying. (AO, 43)

- In the original French text, “re-embody” is written in quotes — not “re-embodying.”

Deleuze and Guattari are referring to Irish novelist and poet James Joyce here. The term “re-embody” appears in Joyce’s Stephen Hero, an autobiographical novel published posthumously in 1944. The following is the exact quote from Stephen Hero:

To equate these faculties was the secret of artistic success: the artist who could disentangle the subtle soul of the image from its mesh of defining circumstances most exactly and re-embody it in artistic circumstances chosen as the most exact for it in its new office, he was the supreme artist. (Collected Works of James Joyce; emphasis mine)

Just as Proust weaves together various elements to create a larger artistic whole — or as the train passenger pieces together different views of the landscape by looking out each window — Joyce follows a similar approach in defining “artistic success.” For Joyce, the true artist is one who extracts “the subtle soul of the image,” uncovering the deepest essence of what they observe by freeing it from its original, limiting context. The artist then re-embodies this essence within a newly chosen artistic form, producing a new whole that emerges alongside the very parts that constitute this artistry, serving as yet another foundation for re-embodiment.

Deleuze and Guattari explicate:

The body without organs is produced as a whole, but in its own particular place within the process of production, alongside the parts that it neither unifies nor totalizes. (AO, 43)

As previously discussed, the whole emerges as a part alongside various parts within the production process. Deleuze and Guattari further clarify that the body without organs is produced as a whole in its own right — continuously produced by the three syntheses while serving as a foundation for them. However, the body without organs cannot be conceptualized as a finality; it exists alongside the parts, creating a unity that never fully unifies, forming a whole that never totalizes. And as this unfolds, the body without organs falls back on the production process, thereby making the process start up again:

And when [the body without organs] operates on them, when it turns back upon them (se rabat sur elles), it brings about transverse communications, transfinite summarizations, polyvocal and transcursive inscriptions on its own surface, on which the functional breaks of partial objects are continually intersected by breaks in the signifying chains, and by breaks effected by a subject that uses them as reference points in order to locate itself. (AO, 43)

The body without organs falls back on the process of production, causing it to start up again. However, it must be clarified that production never truly stops; it is always an ongoing process with the body without organs immediate falling back upon the three syntheses. The falling back on the production process by the body without organs introduces new kinds of connections and disconnections, inscriptions, and consumptions; this keeps the production process in a constant state of flux.

In the quote above, Deleuze and Guattari describe how the body without organs falling back on the production process “brings about transverse communications,” meaning that it enables connections that do not adhere to a linearized, pre-established path. The body without organs also introduces “transfinite summarizations,” indicating that the system of production remains open-ended, never reaching a final, closed totality. When Deleuze and Guattari refer to “polyvocal and transcursive inscriptions,” they are arguing that the body without organs resists organization around a single voice or discourse (a signifier). Instead, inscriptions emerge across multiple chains, disrupting any fixity within a chain. All of these breaks — whether it be by partial objects or breaks within these symbolic chains — are interrelated; all of which contributes to the formation of a subject that traverses the surface of the body without organs. However, this subject never reaches a fixed state; it is continuously emerging in relation to desiring-machines, utilizing breaks as referent points to situate itself without ever becoming fully defined.

Deleuze and Guattari restate their thesis:

The whole not only coexists with all the parts; it is contiguous to them, it exists as a product that is produced apart from them and yet at the same time is related to them. (AO, 43–44)

This is their metaphysics: the whole is produced as a part alongside other parts. The whole is produced apart from the parts — while simultaneously serving as a part that is alongside or related to the parts in the production process.

Deleuze and Guattari continue by relating what we discussed to genetics:

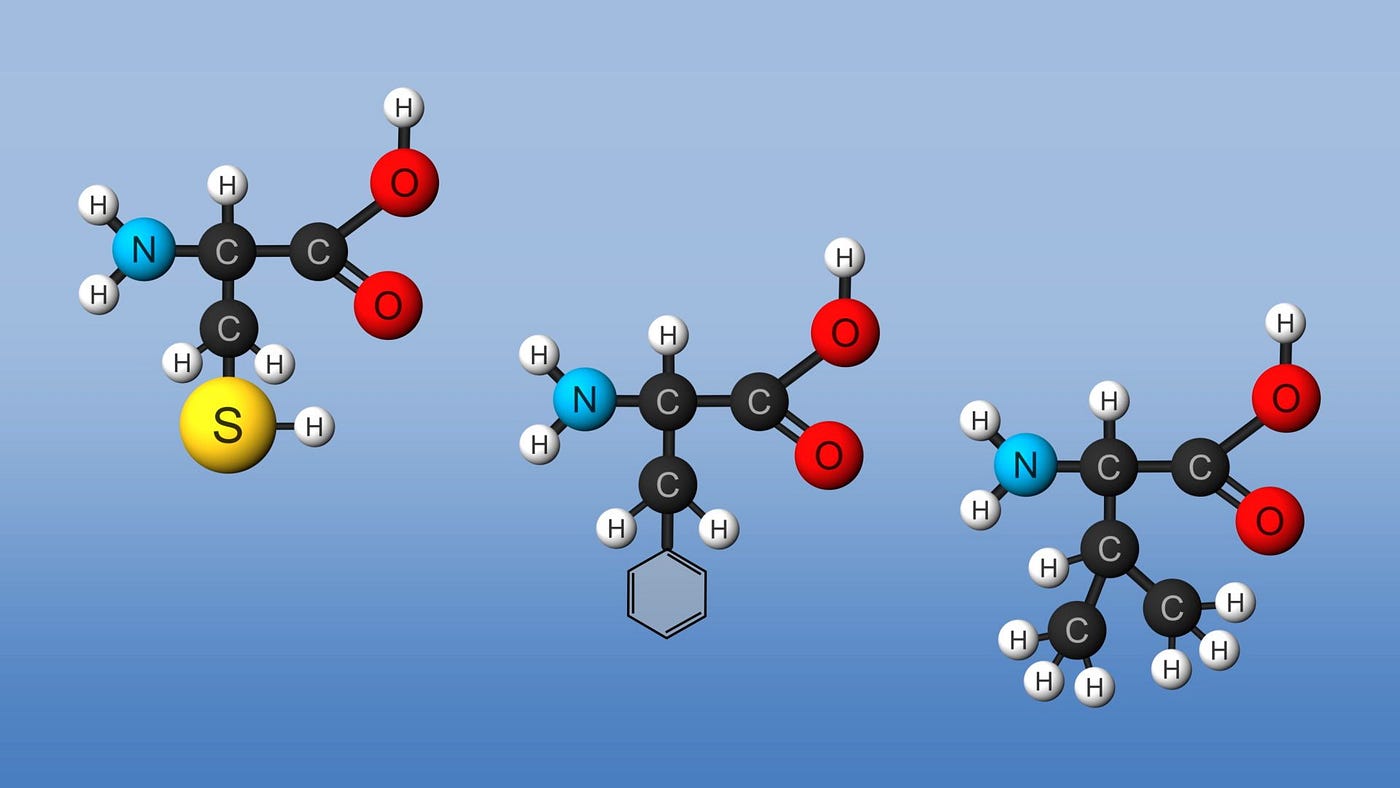

Geneticists have noted the same phenomenon in the particular language of their science: “. . . amino acids are assimilated individually into the cell, and then are arranged in the proper sequence by a mechanism analogous to a template onto which the distinctive side chain of each acid keys into its proper position.” (AO, 44)

They cite Joseph Harold Rush’s 1957 book The Dawn of Life which explores the origins of life, including concepts of abiogenesis and genetics. The reference to amino acids illustrates how a whole emerges alongside its parts without reducing the parts to a mere sum. In genetics, amino acids are not pre-assembled into a unified whole; these acids are “assimilated individually” into a cell and arranged according to a template. This is seen in protein synthesis, where mRNA serves as a blueprint, carrying genetic instructions from DNA. Ribosomes then use this template to assemble amino acids into specific protein structures. Evidently, each amino acid retains its distinctness as a part (“the distinct side chain”) while becoming part of a larger structure — yet, this integration does not erase the distinctiveness of the amino acid.

- I attached the citation for The Dawn of Life in the citations sections.

They continue:

As a general rule, the problem of the relationships between parts and the whole continues to be rather awkwardly formulated by classic mechanism and vitalism, so long as the whole is considered as a totality derived from the parts, or as an original totality from which the parts emanate, or as a dialectical totalization. (AO, 44)

Deleuze and Guattari problematize normative conceptualizations of the whole and its parts:

- The mechanistic view: In this view, where “the whole is considered as a totality derived from the parts,” Deleuze and Guattari critique how it fails to account for the whole emerging alongside its parts. The mechanistic perspective understands the whole as nothing more than a collection of parts working together — like a machine being defined by the sum of its parts.

- The vitalistic view: In this view, the whole is seen as an “original totality from which the parts emanate,” resembling a Neoplatonist framework. This perspective prioritizes the whole as a pre-existing unity, where parts are defined in relation to an ultimate purpose or end. Deleuze and Guattari reject this teleological view, as it subordinates the parts to the whole (and it fails to account for the differentiation of parts writ large).

- The dialectical view: In this teleological view, where the whole emerges through contradictions and their resolve, Deleuze and Guattari critique Hegelian and Marxist dialectics for totalizing the parts by integrating them into a process that moves towards an end goal. This framework fails to recognize that the production process is an ongoing, open-ended, emergent process

Having just critiqued the mechanistic, vitalistic, and dialectical perspectives, they explain:

Neither mechanism nor vitalism has really understood the nature of desiring-machines, nor the twofold need to consider the role of production in desire and the role of desire in mechanics. (AO, 44)

Here, Deleuze and Guattari explicitly argue that the perspectives they criticize fail to grasp the nuanced complexities of desiring-production — particularly how desire functions and operates within this process.

Paragraph Five

Deleuze and Guattari begin this paragraph by once again reaffirming their earlier thesis:

There is no sort of evolution of drives that would cause these drives and their objects to progress in the direction of an integrated whole, any more than there is an original totality from which they can be derived. (AO, 44)

It is evident that parts (machines) are not progressing towards some kind of end goal anymore than they are derived from an original totality. As we have been dealing with parts, Deleuze and Guattari shift the discussion to Klein:

Melanie Klein was responsible for the marvelous discovery of partial objects, that world of explosions, rotations, vibrations. (AO, 44)

Klein is credited with discovering partial objects, marking a significant departure from earlier psychoanalytic theories that began with global persons. As previously noted, Klein’s analysis starts with the infant experiencing the world through unintegrated parts. The infant does not begin with the mother; the infant begins with the breast as a partial object. Although Klein discovered something extremely important, Deleuze and Guattari ask:

But how can we explain the fact that she has nonetheless failed to grasp the logic of these objects? (AO, 44)

Thankfully, they answer their question:

It is doubtless because, first of all, she conceives of them as fantasies and judges them from the point of view of consumption, rather than regarding them as genuine production. (AO, 44)

First, Klein conceptualizes partial objects in terms of fantasies, rooting desire in fantasized objects like the “good” and “bad” breast. While she does not begin with a fully formed subject — describing the ego as unintegrated in the first three months of life —her framework ultimately reinforces the concept of a global person. By treating the infant’s experience of the breast as holistically good or bad, she frames desire in terms of a subject’s relation to consumption rather than the autonomous function of partial objects. Thus, she continues to center a consuming subject, privileging the One over the many, the Whole over the parts. Deleuze and Guattari elaborate:

She explains [partial objects] in terms of causal mechanisms (introjection and projection, for instance), of mechanisms that produce certain effects (gratification and frustration), and of mechanisms of expression (good or bad) — an approach that forces her to adopt an idealist conception of the partial object. (AO, 44)

Deleuze and Guattari argue that Klein fails to grasp the truly productive nature of partial objects, as she situates them within frameworks that remain secondary to the production process. Let us review Klein’s mechanisms now:

- Causal mechanisms: Klein attributes the infant’s introjection of anxiety to the death instinct, leading to the development of various defense mechanisms. These anxieties then become projected onto external objects, like the breast, for example.

- Mechanisms that produce certain effects: Klein finds that the infant engages with the breast as an object of gratification, with the breast satiating hunger or feeling warm, and an object of frustration, where the infant responds destructively such as by biting or hitting the breast.

- Mechanisms of expression: The infant perceives the breast in overarching terms, as holistically good or holistically or bad.

These various mechanisms have never been primary in the production process — they are only secondary. Therefore, Klein views partial objects in an idealized manner. This means that Klein falls back into the very familiar trap of centering the subject:

She does not relate these partial objects to a real process of production — of the sort carried out by desiring-machines, for instance. (AO, 44)

We will further explore how these so-called “pre-oedipalized” remain fundamentally rooted in oedipalization.

Deleuze and Guattari continue to explain their second criticism of Klein.

In the second place, she cannot rid herself of the notion that schizoparanoid partial objects are related to a whole, either to an original whole that has existed earlier in a primary phase, or to a whole that will eventually appear in a final depressive stage (the complete Object).

(AO, 44)

Second, Klein assumes a totality by presupposing that partial objects relate to a unified whole. This assumed whole either preexists or awaits the subject in the future. Consequently, for Klein, schizoparanoid objects appear incomplete, as they either refer back to an original wholeness that has yet to be integrated or anticipate eventual totalization through the development into the depressive stage. In either case, Klein assumes that the subject will ultimately unify these objects.

Furthermore:

Partial objects hence appear to her to be derived from (preleves sur) global persons; not only are they destined to play a role in totalities aimed at integrating the ego, the object, and drives later in life, but they also constitute the original type of object relation between the ego, the mother, and the father. (AO, 44)

For Klein, partial objects are always in relation to global persons — this almost reads like an emanationist model in Neoplatonism. The ultimate goal of these partial objects is to function as parts of a larger totality, remaining incomplete as long as their corresponding global person remains unidentified. Deleuze and Guattari critique this view, arguing that while Klein identifies the breast as a partial object, she still treats it as inherently tied to the global person of the mother. Klein does not recognize the mother as another partial object among many. In this sense, Klein subordinates partial objects to the goal of “integrating the ego, the object, and drives later in life,” making partial objects dependent on a totality. Her model presupposes the ego, the mother, and the father as innate, totalizing wholes.

Notably, Deleuze and Guattari use the term “prélevés sur” (derived from) which echoes their earlier analysis of the first synthesis where they employ the term “coupures-prélevés” (withdrawn cuts/slices) in Chapter 1.5. They seem to be highlighting Klein’s misuse of the first synthesis.

They continue by stating that their twofold criticism of Klein — emphasizing the second point — is necessary:

And in the final analysis that is where the crux of the matter lies. (AO, 44)

- The original French text reads a bit differently: “Now, it is here that everything is decided.” This seems to convey a particular turning point rather than solely an emphasis on their second point.

They proceed by explaining the importance of partial objects:

Partial objects unquestionably have a sufficient charge in and of themselves to blow up all of Oedipus and totally demolish its ridiculous claim to represent the unconscious, to triangulate the unconscious, to encompass the entire production of desire. (AO, 44)

Deleuze and Guattari argue that partial objects possess a “sufficient charge” all by themselves, which is capable of dismantling Oedipus. Throughout Anti-Oedipus, their criticism of the Oedipal complex (as reflected by the book’s title) is evident; they show how Oedipus traps desire within its structure. The notion of Oedipus representing the unconscious was never a priori — it was and continues to be artificially produced. When Deleuze and Guattari refer to the triangulation of the unconscious, they are explaining how Oedipus constrains desire into the rigid “mommy-daddy-me” and “ego-id-superego” configurations. Within this triangular framework, desire is preemptively restricted to Oedipus.

Furthermore:

The question that thus arises here is not at all that of the relative importance of what might be called the pre-oedipal in relation to Oedipus itself, since “pre-oedipal” still has a developmental or structural relationship to Oedipus. (AO, 44–45)

At this juncture, Deleuze and Guattari highlight that the issue is not about the importance of the so-called pre-oedpial state Klein analyzes, where the ego is unintegrated. The pre-oedipal state was never truly before Oedipus; this stage has always upheld the Oedipal framework. To invoke a pre-oedipal stage is to implicitly accept Oedipus as the primary lens of analysis from the outset. Hence, why Deleuze and Guattari characterize such analysis as having a “developmental or structural relationship to Oedipus.”

The focus should not be on pre-oedipal stages:

The question, rather, is that of the absolutely anoedipal nature of the production of desire. (AO, 45)

Here, Deleuze and Guattari are concise: the focus should be on the anoedpial nature of desiring-production. They continue with their criticism of Klein:

But because Melanie Klein insists on considering desire from the point of view of the whole, of global persons, and of complete objects — and also, perhaps, because she is eager to avoid any sort of contretemps with the International Psycho-Analytic Association that bears above its door the inscription “Let no one enter here who does not believe in Oedipus” — she does not make use of partial objects to shatter the iron collar of Oedipus; on the contrary, she uses them — or makes a pretense of using them — to water Oedipus down, to miniaturize it, to find it everywhere, to extend it to the very earliest years of life.

(AO, 45)

As Klein positions desire from the perspective of global persons, it becomes evident that she chooses not to utilize partial objects as a means to break away from and dismantle Oedipus. Her analysis may reflect a fear of deviating too far from the International Psycho-Analytic Association, which upholds Oedipus and avoids questioning its framework. Thus, Klein utilizes partial objects — not to challenge Oedipus — but to reinforce the “iron collar of Oedipus.” From the very start, she makes Oedipus present, framing every stage of life, particularly the earliest stages of infancy, within its schema.

Paragraph Six

Deleuze and Guattari continue:

If we here choose the example of the analyst least prone to see everything in terms of Oedipus, we do so only in order to demonstrate what a forcing was necessary for her to make Oedipus the sole measure of desiring-production. (AO, 45)

Even if an analyst is “least prone” to reducing desiring-production to Oedipus, they are still compelled to “make Oedipus the sole measure of desiring-production.” It is all too easy. Deleuze and Guattari are referring to Klein here, who, despite her relatively less Oedipal approach, remains constrained by the Oedipal framework. Further still:

And naturally this is all the more true in the case of run-of-the-mill practitioners who no longer have the slightest notion of what the psychoanalytic “movement” is all about. (AO, 45)

Unfortunately, if a more thoughtful analyst succumbs to Oedipus, then the “run-of-the-mill practitioners” fall into the same trap. They might have no true conceptualization of the specificities of psychoanalytic theories, yet they still adhere to the Oedipal framework. Deleuze and Guattari write:

It is no longer a question of suggestion, but of sheer terrorism. (AO, 45)

The psychoanalyst terrorizes the patient. They refer to Klein’s analysis:

Melanie Klein herself writes:

“The first time Dick came to me … he manifested no sort of affect when his nurse handed him over to me. When I showed him the toys I had put ready, he looked at them without the faintest interest. I took a big train and put it beside a smaller one and called them ‘Daddy-train’ and ‘Dick-train.’ Thereupon he picked up the train I called ‘Dick’ and made it roll to the window and said ‘Station.’ I explained: ‘The station is mummy; Dick is going into mummy.’ He left the train, ran into the space between the outer and inner doors of the room, shutting himself in, saying ‘dark,’ and ran out again directly. He went through this performance several times. I explained to him: ‘It is dark inside mummy. Dick is inside dark mummy.’ Meantime he picked up the train again, but soon ran back into the space between the doors. While I was saying that he was going into dark mummy, he said twice in a questioning way: ‘Nurse?’ . . . As his analysis progressed . . . Dick had also discovered the wash-basin as symbolizing the mother’s body, and he displayed an extraordinary dread of being wetted with water.”

(AO, 45)

- The original French text has a footnote referencing Melanie Klein’s Essays on Psychoanalysis.

This passage refers to Klein’s The Importance of Symbol-Formation in the Development of the Ego, published in 1930. It is striking that Klein was able to work with children while remaining so firmly trapped within the Oedipal framework. She reduces desiring-production to sexual relations and symbolism at every turn. The train must represent daddy. It must represent the child. It must represent a phallus. The station must represent mommy. The darkness and wash-basin must symbolize mommy. It never ends. Before Dick entered the room, Oedipus was already imposed — he was incapable of escaping:

Say that it’s Oedipus, or you’ll get a slap in the face. (AO, 45)

There is no room to question the validity of Oedipus. If one fails to reply in terms of Oedipus, they are automatically deemed psychotic as something must be wrong with the patient.

Furthermore:

The psychoanalyst no longer says to the patient: “Tell me a little bit about your desiring-machines, won’t you?”

Instead he screams: “Answer daddy-and-mommy when I speak to you!”

Even Melanie Klein.

(AO, 45)

Deleuze and Guattari continue with their criticism of Oedipus:

So the entire process of desiring-production is trampled underfoot and reduced to (rabuttu sur) parental images, laid out step by step in accordance with supposed pre-oedipal stages, totalized in Oedipus, and the logic of partial objects is thereby reduced to nothing. (AO, 45–46)

They argue that the entire production process is trampled and falls back on “parental images,” accompanied by all kinds of sexual symbolism. Notably, Deleuze and Guattari use the term “rabuttu sur” (past tense) a variation of the term “rabat sur” (present tense); they used “rabat sur” when describing the body without organs falling back on the production process. While the translation of “rabbutu sur” as “reduced to” works well in this specific context in the quote above, a broader understanding of this in Deleuze and Guattari’s framework would suggest an interpretation closer to “folded back on” or “falls back on.” Regardless, the terms of Oedipus are imposed from the outset — each step, from the supposed pre-oedipal stages to the final, so-called realization of Oedipus, is laid out in advance, leaving no room for an alternative conceptualization of desire.

Therefore:

Oedipus thus becomes at this point the crucial premise in the logic of psychoanalysis. (AO, 46)

Deleuze and Guattari emphasize that Oedipus is not solely one theory among many in psychoanalysis — it is the foundation on which psychoanalysis relies upon. All desiring-production must conform to this model. Yet, Oedipus was never a priori:

For as we suspected at the very beginning, partial objects are only apparently derived from (prélevés sur) global persons; they are really produced by being drawn from (prélevés sur) a flow or a nonpersonal hyle, with which they re-establish contact by connecting themselves to other partial objects. (AO, 46)

Once again, partial objects may appear to derive from global persons, but in reality, global persons are artificially produced. The first synthesis makes it evident that all partial objects are fundamentally connected via their relation to flows. Partial objects are drawn from, sampled, and extracted from a flow — this is where the term “prélevés sur” comes into play. This kind of withdrawal should not be understood as coming from a global person, but rather from a whole that is already a part among parts. Furthermore, partial objects are produced through their relationship to a material flow, which they cut into and interrupt. This concept recalls the concept of “hyle” from Chapter 1.5, where machines slice into associative flows (“the mouth that cuts off not only the flow of milk but also the flow of air and sound”).

Deleuze and Guattari state:

The unconscious is totally unaware of persons as such. (AO, 46)

The unconscious does not recognize “mommy,” “daddy,” or “me.” The unconscious sis completely unaware of global persons. There are no a priori representations. Assuming these representations exist beforehand is problematic because it misunderstands the unconscious. Partial objects cannot derive from global persons if the unconscious has no awareness of global persons.

They write:

Partial objects are not representations of parental figures or of the basic patterns of family relations; they are parts of desiring-machines, having to do with a process and with relations of production that are both irreducible and prior to anything that may be made to conform to the Oedipal figure. (AO, 46)

Partial objects are not symbols or representations of family members or sexual relations. Instead, they function solely as components of desiring-machines, directly involved in the production process. They cannot be reduced to the Oedipus complex because partial objects exist prior to Oedipus; partial objects remain irreducible to the framework of psychoanalysis.

Paragraph Seven

To continue:

When the break between Freud and Jung is discussed, the modest and practical point of disagreement that marked the beginning of their differences is too often forgotten: Jung remarked that in the process of transference the psychoanalyst frequently appeared in the guise of a devil, a god, or a sorcerer, and that the roles he assumed in the patient’s eyes went far beyond any sort of parental images. (AO, 46)

Deleuze and Guattari begin this paragraph by noting that discussions regarding the split between psychoanalysts Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung often emphasize their larger ideological differences, while neglecting the initial — and more practical — disagreement that marked their beginning of divergence. Jung observed that in the process of transference, where an analysand projects feelings onto an analyst, the resulting images were not always parental. Instead, he noted that patients projected other symbolic figures onto the analyst, such as “a devil, a god, or a sorcerer.” Jung’s observation is important:

[Freud and Jung] eventually came to a total parting of the ways, yet Jung’s initial reservation was a telling one. (AO, 46)

- In the original French text, Deleuze and Guattari write that Jung had a good starting point but went astray in his conclusions.

Deleuze and Guattari expand on Jung’s idea:

The same remark holds true of children’s games. (AO, 46)

The application of Jung’s departure from Freud to children’s games is a strategic move by Deleuze and Guattari. This highlights the reductive nature of confining everything to the analyst’s office. They write:

A child never confines himself to playing house, to playing only at being daddy-and-mommy.

[The child] also plays at being a magician, a cowboy, a cop or a robber, a train, a little car.

The train is not necessarily daddy, nor is the train station necessarily mommy.

(AO, 46)

- In the original French text, Deleuze and Guattari say “sorcerer” instead of “magician” which seems to be a reference to Jung.

Children naturally engage in imaginative play, embodying a wide-array of roles — from magicians and grocery clerks to princess, princesses, and beyond. While they may sometimes play as “daddy-and-mommy,” their play is confined to these roles. It is reductive to assume that children only play as parental roles. Deleuze and Guattari criticize Klein, arguing that the train and train station does not necessarily represent one’s father and mother. While such interpretations are possible, it does not mean they are definitively true.

At this juncture, Deleuze and Guattari clearly identify the problem:

The problem has to do not with the sexual nature of desiring-machines, but with the family nature of this sexuality. (AO, 46)

Desire is not innately familial. Framing the sexual nature of desiring-machines as the problem is a misidentification as desire operates without a reference to global persons; desire knows no global person. The true problem lies in how the Freudian framework erroneously reduces all sexual relations to a familial relation. This triangulation of desire — where everything is interpreted sexually and preconfigured to fit within the mommy-daddy-me dynamic — is the problem.

Deleuze and Guattari further explain:

Admittedly, once the child has grown up, [the individual] finds [themselves] deeply involved in social relations that are no longer familial relations. (AO, 46)

Eventually, the child grows up and becomes involved in various social relations beyond their immediate family, such as relations formed through higher education, work, social clubs, and so on. This poses a challenge for psychoanalysis, which interprets these non-familial relationships through a familial lens. Deleuze and Guattari write (from the standpoint of psychoanalysis):

But since these relations supposedly come into being at a later stage in life, there are only two possible ways in which this can be explained: it must be granted either that sexuality is sublimated or neutralized in and through social (and metaphysical) relations, in the form of an analytic “afterward”; or else that these relations bring into play a nonsexual energy, for which sexuality has merely served as the symbol of an anagogical “beyond.” (AO, 46)

Psychoanalysis offers two possible explanations for how a child becomes an adult and engages in non-familial relations.

The first explanation — a largely Freudian response — is sublimation or neutralization. Sublimation entails the process of redirecting socially unacceptable impulses into socially acceptable behaviors. According to this view, sexuality — in terms of familial relations — does not disappear when a subject enters new social relationships. Instead, the sexual energy is transformed into other endeavors. When Deleuze and Guattari reference social relations, they are referring to the relations that come after the direct familial relations. (The “metaphysical relations” refers to desiring-production and how psychoanalysis sublimates sexuality in desiring-production.) The concept of the analytical “afterward” may refer to how all non-familial relations are deemed secondary in psychoanalysis. However, a more direct reference is how the concept of the “afterward” is present in psychoanalysis, dealing with what Freud called Nachträglichkeit — or deferred action. This refers to an earlier experience in one’s life (particularly a sexual or traumatic experience) only becoming meaningful retroactively or after the fact. It is thus interpreted through the lens of a later event. Lacan reconfigured this concept and labeled it “after-effect” or “after-the-coup.”

The second explanation — a largely Jungian response — is that adults may not be driven by sexual energy at all in these relationships. Instead, these relations bring about a “nonsexual energy” whereby sexuality serves as just another symbol. This symbol is viewed “anagogically” meaning that it is mystical or serves as some kind of stand in for something that is transcendent or “beyond.” The concept of anagogical “beyond” seems to be a reference to Freud’s Beyond the Pleasure Principle, published in 1920. Psychoanalysis analyzes these symbols to find deeper meaning within them. Therefore, even if Jung expands beyond the normative parental images put forth by Freud, he still relies on images.

In both of these cases, psychoanalysis reduces the complexity of all relations by framing them through the lens of symbolism or having some transcendent meaning. It is here that psychoanalysis privileges the One over the many.

Paragraph Eight

The difference between Freud and Jung is more than a simple dispute:

It was their disagreement on this particular point that eventually made the break between Freud and Jung irreconcilable. (AO, 46)

Since Freud and Jung offer contrasting explanation and starting points for transference and the subject’s relations beyond the immediate family, they are diametrically opposed. They are both similar in the respect that they are both extremely reductive:

Yet at the same time the two of them continued to share the belief that the libido cannot invest a social or metaphysical field without some sort of mediation. (AO, 46)

This is the crux of Deleuze and Guattari’s criticism. Both Freud and Jung argue that for libido to invest itself into social or metaphysical relations, some form of mediation is required. For psychoanalysis, a subject’s relationship outside of the family must be viewed through familial sexuality, as Freud suggested, or viewed as symbolic representations of deeper unconscious processes, as Jung proposed. The problem is the assumption that any mediation is necessary at all. The problem is the erroneous need for mediation between libido and the social field. Desiring-production was always already social. As Deleuze and Guattari succinctly state:

This is not the case, however. (AO, 46)

Deleuze and Guattari continue by providing an example:

Let us consider a child at play, or a child crawling about exploring the various rooms of the house [the child] lives in. (AO, 46)

They describe how this child relates to the rooms of the house:

[The child] looks intently at an electrical outlet, [the child] moves [their] body about like a machine, [the child] uses one of [their] legs as though it were an oar, [the child] goes into the kitchen, into the study, [the child] runs toy cars back and forth. (AO, 46–47)

Deleuze and Guattari illustrate the child’s journey through the house, highlighting that the child is a machine composed of various parts, each serving different functions — a leg becomes an oar, for example. Then, quite suddenly, the child moves on, playing with cars and then running back and forth. This vivid depiction of the child prompts us to ask a necessary question: Where does Oedipus fit in?

They continue:

It is obvious that [the child’s] parents are present all this time, and that the child would have nothing were it not for them. (AO, 47)

Clearly, Deleuze and Guattari emphasize the importance of the parents in the child’s life. They child would not be born if it were not for the parents. However, it must be noted that this is not our primary analysis:

But that is not the real matter at issue. (AO, 47)

So … what is the real matter at issue, then? Deleuze and Guattari answer:

The matter at issue is to find out whether everything [the child] touches is experienced as a representative of [their] parents. (AO, 47)

As the child navigates various rooms in the house, Deleuze and Guattari implore us to ask whether objects like the electrical socket or toy are are merely representations of parental figures. Does the toy car represent the father? The mother? Or, are these kinds of questions reductive because they ignore desiring-production? They write:

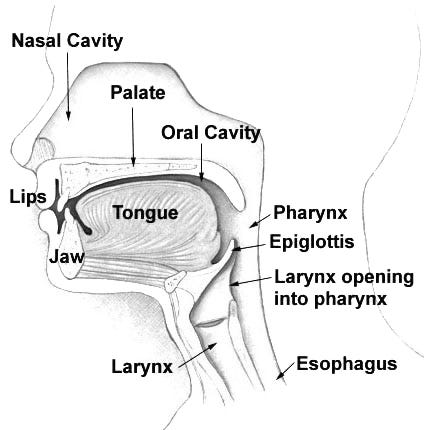

Ever since birth [the child’s] crib, [the child’s] mother’s breast, [the mother’s] nipple, [the child’s] bowel movements are desiring-machines connected to parts of [the child’s] body. (AO, 47)

Desiring-machines connect directly to the child’s body via the connective synthesis, with the child’s body functioning as another machine. From a machinic perspective, no representations are necessary. Here is where Deleuze and Guattar draw out their criticism:

It seems to us self-contradictory to maintain, on the one hand, that the child lives among partial objects, and that on the other hand [the child] conceives of these partial objects as being [the child’s] parents, or even different parts of [the child’s] parents’ bodies. (AO, 47)

This quote is a directly critiques Klein by showing a fundamental contradiction in her analysis. While she conceives of the child experiencing the world through partial objects, she ultimately concludes that these partial objects are only in relation to global persons. For instance, Klein finds that the child experiences the breast as a partial object while simultaneously conceptualizing the breast as a part of the mother as a unified whole.

Deleuze and Guattari correct Klein’s error:

Strictly speaking, it is not true that a baby experiences [their] mother’s breast as a separate part of [the mother’s] body. (AO, 47)

The baby does not experience the breast as separate from the mother’s body:

[The breast] exists, rather, as a part of a desiring-machine connected to the baby’s mouth, and is experienced as an object providing a nonpersonal flow of milk, be it copious or scanty. (AO, 47)

When examined in the context of desiring-machines, we do not find global persons. The breast solely functions as a machine connected to other machines — in this case, the mouth-machine of the baby. Even as the child grows up, they do not retroactively view the mother’s breast as something symbolic. From a machinic perspective, all that we find is a breast-machine plugged into a mouth-machine, one emitting a flow that the other interrupts. Deleuze and Guattari note this flow of milk as “nonpersonal,” emphasizing that this analysis does not deal with a subjectivity a priori (global persons).

- Deleuze and Guattari highlight the flow of milk being “copious” or “scanty” (meaning a large or small quantity of milk). This appears to directly respond to Klein, who interprets the infant’s experience of the breast as projections of “good” or “bad.” For example, if the milk is insufficient, the infant may hit or bite the breast out of frustration; her analysis is specific to the death drive. However, Deleuze and Guattari reject this as they do not find the actions of hitting, biting, or even suckling (this would be the life instinct for Klein) to be symbolic. This is all purely machinic as the hand-machine becomes a hitting-machine and the mouth-machine transforms into a biting-machine depending on particular connections and disconnections present.

Deleuze and Guattari explain:

A desiring-machine and a partial object do not represent anything.

A partial object is not representative, even though it admittedly serves as a basis of relations and as a means of assigning agents a place and a function; but these agents are not persons, any more than these relations are intersubjective.

(AO, 47)

Representations arise only when we are dealing with global persons. The breast and mouth, train and train station, electrical socket and toy car are not representations — they are machines. Though machines are not representative of everything, partial objects do establish specific functions and roles in machinic systems; howeber, none of this assumes the establishment of a unified whole or roles that serve as the presence of a Cartesian subject. For example, the breast-machine and mouth machine — along with the child-machine and mother-machine composed of all kinds of machines — are not reducible to parts of a global person or global persons in and of themselves.

Furthermore, the relations between various machines are not “intersubjective” as they do not involve symbolic meaning or depend on being defined exclusively to others. This is a pointed critique of Lacan, particularly his concept of the “intersubjective modulus,” which describes how signifiers acquire meaning by not being other signifiers within the symbolic order. Lacan develops this extensively in his seminar on The Purloined Letter, where he emphasizes how subjectivity is constitued by an interplay of signifiers defined exclusively (a dog is not a cat, not a hat, not a blog, etc.). Deleuze and Guattari argue that machines are not defined intersubjectively.

If machines, then, are not defined exclusively, how might we conceptualize their relations between one another? Deleuze and Guattari answer:

They are relations of production as such, and agents of production and antiproduction. (AO, 47)

Thus, these relations are “relations of production,” meaning that machines are understood by their capacities, connections and disconnections, recordings, and consumptions. When Deleuze and Guattari refer to “agents of production and antiproduction,” they are showing how machines are nonpersonal. These agents are both produced by and produce the production process, while also producing antiproduction (the body without organs).

To continue:

Ray Bradbury demonstrates this very well when he describes the nursery as a place where desiring-production and group fantasy occur, as a place where the only connection is that between partial objects and agents. (AO, 47)

Deleuze and Guattari reference American author Ray Bradury’s text The Illustrated Man, published in 1951. In this text, Bradbury presents the nursery as a site where both desiring-production and group fantasy unfold. In Chapter 1.4, Deleuze and Guattari argue that fantasies are never individual — they inherently relate to groups. Concepts like “woman,” “American,” and “family” are group fantasies as these terms only have meaning in a collective context. Bradbury’s work exemplifies how desiring-production and social production are two aspects of the same process — group fantasies are shaped by both desiring-machines and social machines. Deleuze and Guattari write:

The small child lives with [their] family around the clock; but within the bosom of this family, and from the very first days of [the child’s] life, [the child] immediately begins having an amazing nonfamilial experience that psychoanalysis has completely failed to take into account. (AO, 47)