55 min read

·

Processual Becomings

In Chapter 1.1, 1.2, and 1.3, we find a detailed analysis of the three syntheses of the unconscious. Furthermore, in Chapter 1.4, we encountered a detailed analysis of the history of schizophrenia, along with an exploration of the complex relationship between capitalism and schizophrenia.

In this section, Deleuze and Guattari summarize the three syntheses of the unconscious.

Note 1: I will constantly be revising this blog post in order to do a line-by-line interpretation of the text.

Note 2: Since this section summarizes the three syntheses, I will organize it by labeling each part with the corresponding synthesis title.

*Citation Note: Full citation provided at the end of this post

Production of Production / Connective Synthesis

Paragraph One

Deleuze and Guattari begin this section with a rhetorical question:

In what respect are desiring-machines really machines, in anything more than a metaphorical sense? (AO, 36)

As they have repeatedly argued, desiring-machines are literal machines, not figurative ones. Deleuze and Guattari elaborate by saying:

A machine may be defined as a system of interruptions or breaks (coupures). (AO, 36)

When Deleuze and Guattari speak of ‘breaks‘ in the first synthesis, they refer to how machines disconnect from other machines—for example, a mouth-machine disconnecting from a breast-machine. However, these breaks do not signify a separation from reality:

These breaks should in no way be considered as a separation from reality; rather, they operate along lines that vary according to whatever aspect of them we are considering. (AO, 36)

Thus, a break may indicate a disconnection, yet it simultaneously creates a new connection:

Every machine, in the first place, is related to a continual material flow (hyle) that it cuts into. (AO, 36)

- The word “hyle” will be defined by Deleuze and Guattari shortly.

Deleuze and Guattari isolate that this process — the first synthesis of the unconscious — functions like that of a ham-slicing machine:

It functions like a ham-slicing machine, removing portions* from the associative flow: the anus and the flow of shit it cuts off, for instance; the mouth that cuts off not only the flow of milk but also the flow of air and sound; the penis that interrupts not only the flow of urine but also the flow of sperm. (AO, 36)

- *The translators have a note regarding the translation, stating that Deleuze and Guattari use the word “pretevement” to describe this process.

Although a break from a machine might seem to halt a flow, Deleuze and Guattari observe that:

Each associative flow must be seen as an ideal thing, an endless flux, flowing from something not unlike the immense thigh of a pig. (AO, 36)

The comparison of an associative flow originating from something akin to the thigh of a pig serves as a vivid metaphor. The pig’s thigh symbolizes an abundant, seemingly endless source of material. Simply put, there is a continuous flow of desire flowing through machines, with each machine cutting into this flow by ‘removing portions’ from its associative flows. So, while a mouth-machine disconnecting from a breast-machine may seem to end the flow, the flow itself remains endless as each machine connects to other machines. As mentioned earlier, the term hyle represents this continual flow that each machine cuts into. Deleuze and Guattari clarify this concept further:

The term hyle in fact designates the pure continuity that any one sort of matter ideally possesses. (AO, 36)

Deleuze and Guattari were deeply influenced by 17th-century philosopher Baruch Spinoza, and it is crucial to remember Spinoza’s one-substance model. In this model, everything is understood as a single substance that takes on various forms. The term hyle evokes this concept, as Deleuze and Guattari view all types of matter — regardless of their form — as possessing a fundamental, unbroken continuity. To illustrate this, Deleuze and Guattari use an example:

When Robert Jaulin describes the little balls and pinches of snuff used in a certain initiation ceremony, he shows that they are produced each year as a sample taken from “an infinite series that theoretically has one and only one origin,” a single ball that extends to the very limits of the universe. (AO, 36)

Interestingly, Deleuze and Guattari reference the French ethnologist Robert Jaulin, likely drawing from his experiences and travels in Africa — specifically Chad, where his 1967 book La Mort Sara examines the Sara people’s perspectives on death. Rather than approaching death as a universal existential void, Jaulin explores it as a culturally specific process, shaped by the unique beliefs and rituals of the Sara people. The Sara peoples had various initiation rituals — which Jaulin passed himself. In the initiation ceremony that Deleuze and Guattari cite, it appears that the Sara people used small balls of dirt from the earth in their ceremony (I believe)— with this dirt representing continuity or a cyclical understanding of existence.

To reiterate, breaks are not a separation from reality:

Far from being the opposite of continuity, the break or interruption conditions this continuity: [a machine] presupposes or defines what it cuts into as an ideal continuity. (AO, 36)

This “ideal continuity” suggests that when one machine disconnects from another, it should not be viewed as problematic. A disconnection does not imply that a machine is entirely severed or holistically detached from the machine it was previously linked to. Deleuze and Guattari elaborate further:

This is because, as we have seen, every machine is a machine of a machine. (AO, 36)

Since every machine operates as a component of another machine, their interactions consist solely of emissions and interruptions, connections and disconnections, with a flow of desire that binds them together:

The machine produces an interruption of the flow only insofar as it is connected to another machine that supposedly produces this flow. And doubtless this second machine in turn is really an interruption or break, too. (AO, 36)

From the standpoint of the break between two machines, it might seem as though they are distinctly separated; however, it is a mistake to consider these machines in isolation. Only when a third machine comes into play can we fully understand this process:

But it is such only in relationship to a third machine that ideally — that is to say, relatively — produces a continuous, infinite flux: for example, the anus-machine and the intestine-machine, the intestine-machine and the stomach-machine, the stomach-machine and the mouth-machine, the mouth-machine and the flow of milk of a herd of dairy cattle (“and then . . . and then . . . and then . . .”).

(AO, 36)

As outlined in Chapter 1.1, the first synthesis of the unconscious is characterized by the phrase “and then … and then … and then …,” emphasizing the interconnected nature of all machines. Consequently, organ-machines — or rather, all machines in general — should never be considered in isolation; they are invariably linked to all other machines via the connective synthesis. To define this simply, Deleuze and Guattari write:

In a word, every machine functions as a break in the flow in relation to the machine to which it is connected, but at the same time is also a flow itself, or the production of a flow, in relation to the machine connected to it. (AO, 36)

The first synthesis of the unconscious — known as the connective synthesis — is also referred to by another name that Deleuze and Guattari use to link their three syntheses to the three modes of production.

This is the law of the production of production.

(AO, 36; emphasis mine)

They continue:

That is why, at the limit point of all the transverse or transfinite connections, the partial object and the continuous flux, the interruption and the connection, fuse into one: everywhere there are breaks-flows out of which desire wells up, thereby constituting its productivity and continually grafting the process of production onto the product. (AO, 36–37; emphasis mine)

When Deleuze and Guattari refer to transverse and transfinite connections, they are describing how desiring-machines are interconnected and never exist in isolation. Transverse refers to the intersection of machines, while transfinite suggests that the connections made between machines extend beyond finite limits but aren’t infinite: there is infinite potentiality, but finite actualizations.

To understand this more clearly, the ‘limit point’ of these connections refers to the end of the line: the anus-machine connects to the intestine-machine, the intestine-machine to the stomach-machine, and so on. What culminates at the end of these connections is a ‘limit point’. However, at this exact point, the product — the result of these connections — is not a final product. Instead, the process of production grafts itself onto the product, allowing the entire cycle to restart through a system of breaks. These breaks are not separations but interruptions that define and shape the flow, perpetuating the producing-product relationship.

To conclude this paragraph, Deleuze and Guattari make an astute observation:

(It is very curious that Melanie Klein, whose discovery of partial objects was so far-reaching, neglects to study flows from this point of view and declares that they are of no importance; she thus short-circuits all the connections.)* (AO, 37)

Melanie Klein, the Austrian-British psychoanalyst, plays a more prominent role in Chapter 1.6. However, Deleuze and Guattari point out that while Klein discovered partial objects and provided a “far-reaching” analysis of them, she did not explore flows as part of a binary-linear series that spreads in all directions; she did not conceptualize the law of the production of production. *In their footnote, they specifically reference Klein’s 1932 work The Psycho-Analysis of Children to highlight how close she came to this insight:

Children of both sexes regard urine in its positive aspect as equivalent to their mother’s milk, in accordance with the unconscious, which equates all bodily substances with one another.

Paragraph Two

In this paragraph, Deleuze and Guattari examine the specific case study of Little Joey:

“Connecticut, Connect-I-cut!” cries little Joey. (AO, 37)

Drawing from Austrian psychologist Bruno Bettelheim’s 1967 book, The Empty Fortress, Deleuze and Guattari draw from the case of Little Joey in order to explicate their analysis of desiring-machines. In The Empty Fortress, Bettelheim recounts how Little Joey says “Connecticut, Connect-I-cut,” which Deleuze and Guattari use as a metaphor to describe how Little Joey is referring to connections and cuts (disconnections). They continue:

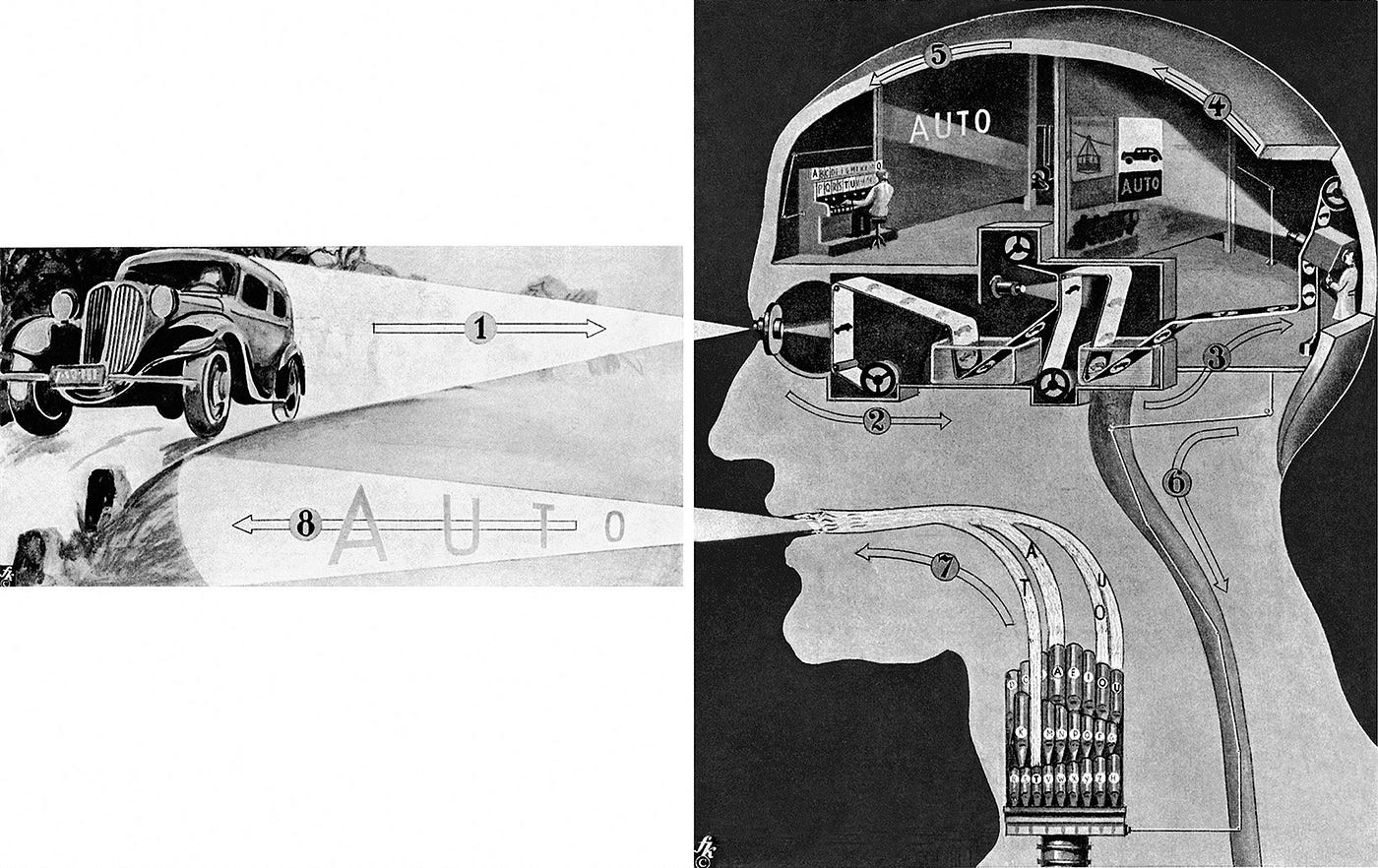

In his study The Empty Fortress, Bruno Bettelheim paints the portrait of this young child who can live, eat, defecate, and sleep only if he is plugged into machines provided with motors, wires, lights, carburetors, propellers, and steering wheels: an electrical feeding machine, a car-machine that enables him to breathe, an anal machine that lights up. (AO, 37)

Deleuze and Guattari use vivid imagery to highlight Bettelheim’s portrayal of Little Joey, whose existence is entirely defined by his relationship with machines. Whether connected to an electrical feeding machine or a car-machine, Little Joey can only navigate and traverse the surface of the body without organs by being plugged into these mechanical systems. Bettelheim’s case study is further praised by Deleuze and Guattari:

There are very few examples that cast as much light on the regime of desiring-production, and the way in which breaking down constitutes an integral part of the functioning, or the way in which the cutting off is an integral part of mechanical connections. (AO, 37)

Ultimately, the disconnection and breakdown of machines is an essential part of their functioning. When a machine is ‘cut off’ from others, it creates the opportunity for new connections to emerge.

This thorough analysis of machines fails to stop critics from objecting:

Doubtless there are those who will object that this mechanical, schizophrenic life expresses the absence and the destruction of desire rather than desire itself, and presupposes certain extremely negative attitudes on the part of his parents to which the child reacts by turning himself into a machine. (AO, 37)

The critics Deleuze and Guattari refer to are those who reduce schizophrenia to the “mommy-daddy-me” triangle, fitting desire into the familiar, Oedipal framework. Traditional psychoanalysts view Little Joey’s condition as a result of negative attitudes from his parents (such as inadequate nurturing), which leads him to retreat into a mechanical existence. In contrast, Deleuze and Guattari conceptualize the schizophrenic as always existing in a mechanical state, where connections are continually made and broken. This state of connections and breaks is the true expression of desire. None of this suggests that Deleuze and Guattari dismiss the influence of Little Joey’s upbringing on his behavior. Instead, they approach this case study by viewing desire as a productive process rather than as lack or absence. They do not interpret Joey’s actions as a traditional defense mechanism, but rather, as the workings of machines making connections breaking them.

Though Bettelheim falls into the trap of Oedipus, he does acknowledge a crucial aspect that challenges a purely determinist view of child development:

But even Bettelheim, who has a noticeable bias in favor of Oedipal or pre-oedipal causality, admits that this sort of causality intervenes only in response to autonomous aspects of the productivity or the activity of the child, although he later discerns in him a nonproductive stasis or an attitude of total withdrawal. (AO, 37)

Bettelheim acknowledges a crucial point: the Oedipal structure itself does not simply dictate the child’s development from the outset, but instead intervenes in response to the child’s autonomous activity. In other words, Bettelheim recognizes that the child is not a passive entity shaped solely by external forces as there is an “autonomous aspect” pertaining to the child’s activity. This indicates the productive nature of desiring-production whereby Little Joey connects and disconnects to various machines; yet, even when Bettelheim admits that there is an autonomous aspect to the nature of desiring-production, he reduces particular connections and disconnections — even if they were autonomously produced — to a “nonproductive stasis” or “withdrawal.” As Bettelheim famously declared “refrigerator mothers” (mothers who were cold and distant towards their children) as the cause of a child’s withdrawal, any autonomous aspect that Bettelheim could’ve noted inevitably becomes blocked by Oedipus.

Again, this is not to imply that the mother has no influence on the child; rather, we must avoid reducing desiring-production to the ever-so-distant mother:

Hence there is first of all, according to Bettelheim, an autonomous reaction to the total life experience, of which the mother is only a part. (AO, 37; emphasis mine)

Furthermore, we must avoid reducing machines — regardless of the specific connections and disconnections — to the repression of desire:

Also we must not think that the machines themselves are proof of the loss or repression of desire (which Bettelheim translates in terms of autism). (AO, 37)

Bettelheim interprets Little Joey’s interactions with machinery as symptomatic of autism, which he associates with repression and withdrawal. He views the machines Little Joey is “plugged into — such as feeding-machines and breathing-machines — as symbolic of lack or deficiency, interpreting the specific nature of these machines as evidence of repressed desire. However, Deleuze and Guattari reject this pathologizing interpretation. In their view, Little Joey is not defined by what he is lacking or what is repressed but by how desire operates. Desire is not rooted in lack; it is productive and machinic. Although Little Joey is, in part, affected by his upbringing, these influences do not reduce his connections to machines as mere reactive responses. Little Joey’s machines highlight the productive nature of desire. At this point, a slew of questions arise:

We find ourselves confronted with the same problem once again: How has the process of the production of desire, how have the child’s desiring-machines begun to turn endlessly round and round in a total vacuum, so as to produce the child-machine? How has the process turned into an end in itself? Or how has the child become the victim of a premature interruption or a terrible frustration? (AO, 37)

Deleuze and Guattari contend that the issue should not be framed around Little Joey’s perceived lack. Instead, we must examine how his desire has been shaped and understood, particularly in terms of how Little Joey’s desiring-machines are placed in a vacuum, isolated from the world. What is crucial is that desire is inherently productive. In Little Joey’s case, Deleuze and Guattari explore how this productive process may have been interrupted, leading desire to become a self-contained loop or turned into an end goal, instead of continuing as an ongoing process.

They continue by framing the case of Little Joey in relation to the body without organs:

It is only by means of the body without organs (eyes closed tight, nostrils pinched shut, ears stopped up) that something is produced, counterproduced, something that diverts or frustrates the entire process of production, of which it is nonetheless still a part. (AO, 37–38)

Whether the production of desire is interrupted or “frustrated,” this interruption — or transformation of the process into an end goal — remains situated on the body without organs. The production of desire does not exist in relation to lack in any transcendent manner as everything is upon the body without organs.

Deleuze and Guattari conclude this section by emphasizing the necessity of understanding machines as desire itself:

But the machine remains desire, an investment of desire whose history unfolds, by way of the primary repression and the return of the repressed, in the succession of the states of paranoiac machines, miraculating machines, and celibate machines through which little Joey passes as Bettelheim’s therapy progresses. (AO, 38)

This quote critiques teleological perspectives on history, which view history as a linear progression toward a predetermined endpoint. Instead, Deleuze and Guattari present the history of desire as non-teleological, emphasizing how the interplay between the paranoiac-machine and the miraculating-machine generates intensities that the celibate machine bands together, leading to the subject’s act of consumption. In this view, history is always emergent with the subject consuming intensive quantities.

Production of Recording / Disjunctive Synthesis

Paragraph Three

After outlining the first synthesis — the production of production — Deleuze and Guattari move on to discuss the second synthesis: the production of recording. They explain:

In the second place, every machine has a sort of code built into it, stored up inside it. (AO, 38)

In Chapter 1.2, we observed that the process of recording involves inscribing points onto the surface of the body without organs. This act of recording imparts a specific functionalism to the machines:

This code is inseparable not only from the way in which it is recorded and transmitted to each of the different regions of the body, but also from the way in which the relations of each of the regions with all the others are recorded. (AO, 38)

The “code” present in a machine is directly connected to how it is recorded and distributed across the various parts of the body without organs. This code not only influences the specific machine it belongs to but is also inseparable from how each region of the body without organs interacts with and relates to the others. Furthermore, machines aren’t fixed. To illustrate how a code embedded in a machine is recorded and transmitted to different parts of the body without organs, affecting various regions, Deleuze and Guattari use the example of the mouth-machine:

An organ may have connections that associate it with several different flows; it may waver between several functions, and even take on the regime of another organ — the anorectic mouth, for instance. (AO, 38)

However, amidst all these different functions a machine can serve, which function should a machine prioritize? Deleuze and Guattari therefore present a series of questions:

All sorts of functional questions thus arise: What flow to break? Where to interrupt it? How and by what means? What place should be left for other producers or antiproducers (the place of one’s little brother, for instance)? Should one, or should one not, suffocate from what one eats, swallow air, shit with one’s mouth? (AO, 38)

Each time a machine forms a connection or disconnection, initiates or halts a flow, this action is imprinted on the body without organs:

The data, the bits of information recorded, and their transmission form a grid of disjunctions of a type that differs from the previous connections. (AO, 38)

In the case of a mouth-machine, it’s clear that it forms various connections: a mouth-machine linked to a thumb-machine, a breast-machine, a door-knob-machine, and so on. With each connection and disconnection, this “data” is recorded, and over time, these machines develop a functionality that is constantly evolving. Deleuze and Guattari attribute the discovery of a machine’s code to French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan:

We owe to Jacques Lacan the discovery of this fertile domain of a code of the unconscious, incorporating the entire chain — or several chains — of meaning: a discovery thus totally transforming analysis. (The basic text in this connection is his La lettre volee [The Purloined Letter]). (AO, 38; emphasis mine)

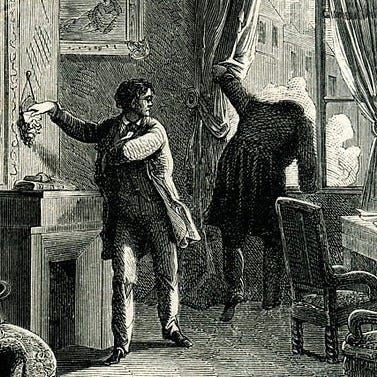

Lacan’s seminar on The Purloined Letter refers to and provides a psychoanalytic analysis of American author Edgar Allan Poe’s 1844 short story of the same name. You can find my sentence-by-sentence reading of Lacan’s seminar The Purloined Letter here. Additionally, you can watch an in-depth group reading of this seminar that I held with friends here. The videos are lengthy, but they offer a comprehensive analysis of the seminar.

Regardless, I’ll discuss Poe’s The Purloined Letter now. Then, I will discuss Lacan’s interpretation of this story.

Enter the Little Black Library

Poe’s story begins with a narrator and his friend, Dupin, smoking tobacco pipes in a small, dark library — or book-closet — at Dupin’s house. Their tobacco session is interrupted by Monsieur G., the Prefect of the Parisian policy and longtime acquaintance of Dupin. The Prefect shares with them a troubling case: a letter has been stolen from the Queen. The contents of the letter are such that whoever possesses it holds power over the Queen, placing her at their mercy. The Prefect reveals that the thief is Minister D., who stole the letter after seeing it at the Queen’s residence and replaced it with a letter he already had on his person.

The Prefect explains that he was tasked with the primary goal of recovering the letter, as a significant reward is being offered for its return. He recounts how he and his officers conducted an exhaustive search of Minister D.’s premises while the Minister was away. Using advanced microscopes and resorting to extreme measures, they examined every possible hiding place — and even dismantled furniture — but their efforts were fruitless.

At this point, the Prefect turns to Dupin and the narrator for advice. Dupin suggests that the Prefect conduct another thorough search , and the Prefect departs to do so. However, Dupin already has a plan in mind. He realizes that the Prefect is approaching the case as though it were a complex mathematical problem, searching for the letter in the most obscure and unlikely places. In reality, the letter might be in plain sight.

Understanding this flaw in the Prefect’s reasoning, Dupin takes matters into his own hands. During a time when the Prefect is not present at the premises, Dupin visits Minister D. under the guise of casual socializing. During their conversation, Dupin notices the stolen letter openly displayed in a card rack — a simple and inconspicuous location. The letter is folded and dirtied to appear unimportant.

Dupin departs without taking the letter and devises a plan to retrieve it. On a subsequent visit, he stages a commotion outside Minister D.’s window, creating a distraction. While the Minister is preoccupied with the disturbance, Dupin swaps the stolen letter with a prepared decoy.

Back at the small, dark library — or book-closet — the narrator and Dupin are once again approached by the Prefect who asks for advice and tells the narrator and Dupin that he would happily give someone a chunk of the reward for producing the letter. Here, Dupin makes sure the Prefect puts his money where his mouth is and has the Prefect write a check out to him, telling the Prefect that once the check is signed, he will provide the letter. Once the check is signed and given to Dupin, Dupin hands the letter to the Prefect who then hurries away.

The moment when the narrator and Dupin reflect on what just happened underscores the story’s moral: we often overcomplicate things, while the answers we seek are right in front of us.

Exit the Little Black Library … Enter the Clinic

Lacan analyzes the short story The Purloined Letter through a psychoanalytic lens, using it to explore the concept of repetition automatism — the unconscious repetition of certain behaviors. He writes:

Our inquiry has led us to the point of recognizing that the repetition automatism finds its basis in what we have called the insistence of the signifying chain. (Lacan’s Seminar on The Purloined Letter)

An example of repetition automatism might look like someone repeatedly checking if a door is locked or experiencing recurring intrusive thoughts. In The Purloined Letter, Lacan identifies a repetitive structure in the story: the letter is repeatedly stolen and concealed. Additionally, he observes that the characters are interconnected within what he terms an “intersubjective modulus,” where the narrative’s progression depends on the interdependence of the characters’ actions.

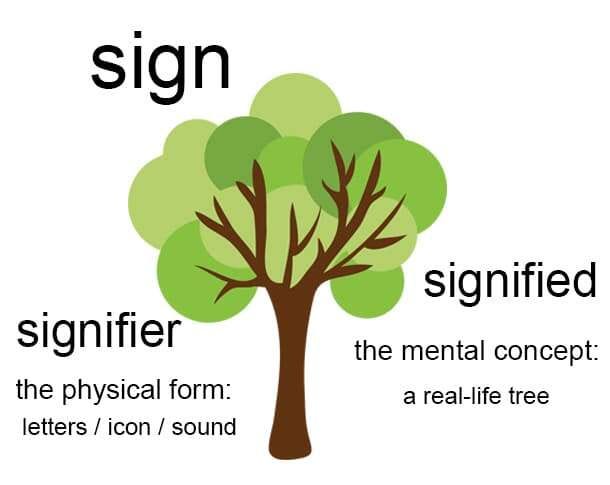

In this seminar, Lacan primarily focuses on the symbolic order — one of the three registers in Lacanian psychoanalysis. The symbolic order refers to the system of norms, language, laws, and institutions that structures subjectivity and mediates our relationship with the world. Lacan conceptualizes the symbolic order as a chain — “signifying chain” — in which everything is interlinked. For example, if we consider the word “dog,” it’s meaning emerges by what it does not signify: it is not a cat, a tree, a cup, a blog post, and so on. This interrelated chain — dog-cat-tree-cup-blog-post-whatever — highlights the relational nature of meaning.

However, Lacan recognizes that this chain is fluid, with the terms that define “dog” continually shifting. To account for this instability, Lacan notes the existence of a “pure signifier” — a signifier without an associated signified — within the chain. In The Purloined Letter, neither the reader nor a majority of the characters know the contents of the letter, making the letter a pure signifier. Despite the absence of a signified, the story progresses. Lacan argues that the position of the pure signifier within the chain determines repetition automatism. He writes:

We shall see that [the subjects’] displacement is determined by the place which a pure signifier — the purloined letter — comes to occupy in their trio. And that is what will confirm for us its status as repetition automatism.

(Lacan’s Seminar on The Purloined Letter; emphasis mine)

Even though the letter is diverted from its original path, it ultimately reaches its intended destination, showing the progression of the story through repetition. Therefore, the unconscious operates according to a code — a system that determines how signs and significations are structured and how the position of the pure signifier within the chain influences the subject.

Exit the Clinic

Deleuze and Guattari draw from Lacan’s seminar to examine the disjunctive synthesis. Let’s refer to their quote from above:

We owe to Jacques Lacan the discovery of this fertile domain of a code of the unconscious, incorporating the entire chain — or several chains — of meaning: a discovery thus totally transforming analysis.

(AO, 38; emphasis mine)

It is evident that there is a code attributed to the unconscious which resembles Lacan’s analysis of the signifying chain. In Lacanian terms, this chain represents a structure where each sign is interconnected with every other sign, forming a network of meaning — with this meaning dependent on where signs are situated within this chain. These signs and signifiers, interconnected in a series of chains, function within a network where they exchange roles and positions in repetitive patterns. Through this process, they develop a system of codes, establishing a functional logic for their operation.

Deleuze and Guattari, however begin to criticize Lacan’s formulation of the signifying chain. They write:

But how very strange this domain seems, simply because of its multiplicity — a multiplicity so complex that we can scarcely speak of one chain or even of one code of desire. (AO, 38)

When speaking of Lacan’s signifying chain, Deleuze and Guattari are hesitant to speak of a signifying chain in a singular sense. There isn’t a single code of desire, but instead a multiplicity that constitutes the domain of the unconscious. They continue:

The chains are called “signifying chains” (chaines signifiantes) because they are made up of signs, but these signs are not themselves signifying. (AO, 38)

Deleuze and Guattari recognize that the chains themselves are made up of signs, but push back against the chains having any kind of signification. They criticize signification writ large, which we will get to shortly. Instead of Lacan’s structuring of the unconscious like that of a language, Deleuze and Guattari find the unconscious to resemble something else:

The code resembles not so much a language as a jargon, an open-ended, polyvocal formation. (AO, 38)

Unlike the unconscious, which in traditional language theory is seen as a system where signs have fixed meanings regardless of context, Deleuze and Guattari view the unconscious as resembling a jargon, where the meaning of signs is dependent upon the context in which they appear, constantly shifting with each interaction. The unconscious is open-ended, not reliant on the placement of a pure signifier. Furthermore:

The nature of the signs within it is insignificant, as these signs have little or nothing to do with what supports them.

Or rather, isn’t the support completely immaterial to these signs?

(AO, 38)

For Deleuze and Guattari, the signs don’t support themselves making the nature of them unimportant. Only in psychoanalysis do the signs support themselves through their reference to each another (such as through definitions, grammar, rules, etc.). Instead, the support must be something immaterial to the signs:

The support is the body without organs. (AO, 38)

The signs serve as points inscribed upon the surface of the body without organs; thus, the body without organs acts as the support for the (a)signifying chains. However, the body without organs is in a state of flux, resisting all forms of organization; this allows for the fluidity of the signs and their connections and disconnections from one another. Thus, a pure signifier isn’t needed in Deleuze and Guattari’s analysis — the signifier isn’t needed at all. Deleuze and Guattari write:

These indifferent signs follow no plan, they function at all levels and enter into any and every sort of connection; each one speaks its own language, and establishes syntheses with others that are quite direct along transverse vectors, whereas the vectors between the basic elements that constitute them are quite indirect. (AO, 38)

- The word “vectors” is not written in the original French text.

With each sign speaking its own language, it becomes clear that Lacan reduces the unconscious to a singular structure. There is no hidden sign waiting to be uncovered, nor is there a single sign responsible for repetition automatism. Instead, signs establish connections and disconnections with one another, inscribing points onto the surface of the body without organs. Deleuze and Guattari use transversal terms to describe how signs interact across different systems in various ways. One way is direct whereby signs cut across different elements (without mediation), linking to other signs or chains that would not normally be connected directly. Another way is indirect where signs operate within the basic elements of a chain, with signs relating to one another via mediation.

Paragraph Four

Deleuze and Guattari continue:

The disjunctions characteristic of these chains still do not involve any exclusion, however, since exclusions can arise only as a function of inhibiters and repressers that eventually determine the support and firmly define a specific, personal subject.* (AO, 38–39)

*There is a footnote at the end of this sentence:

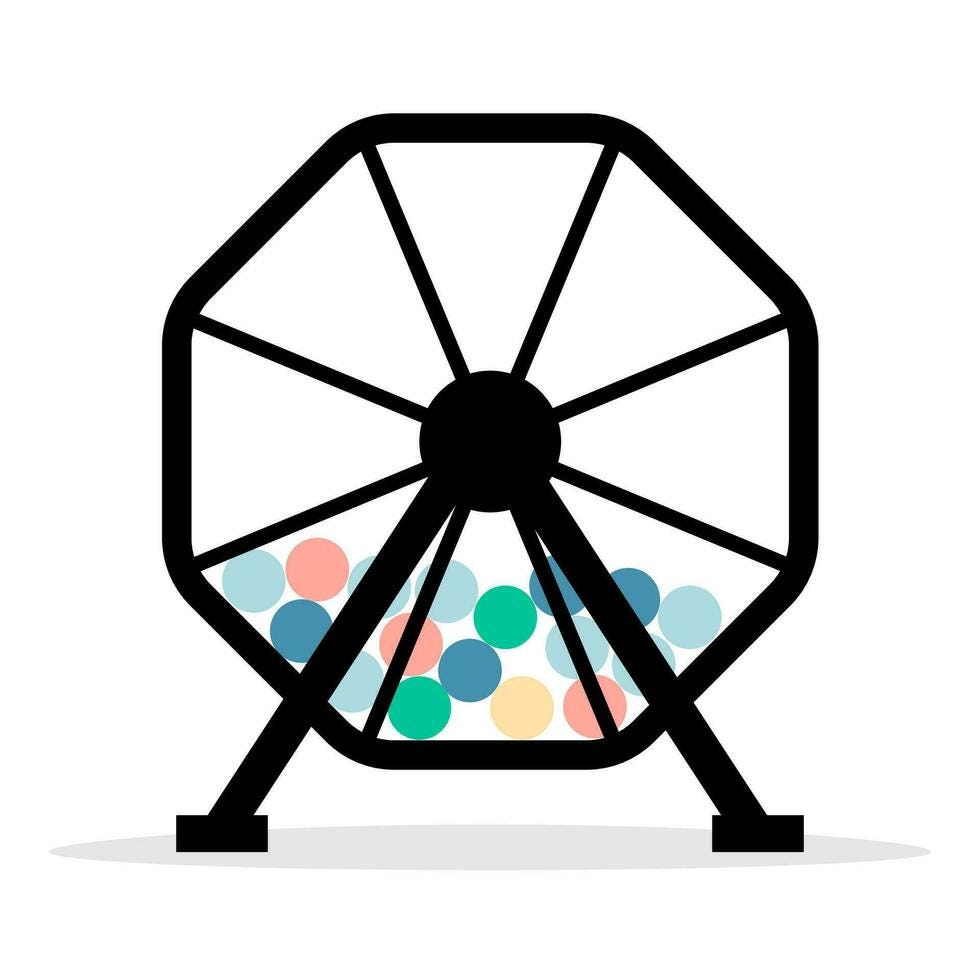

*See Jacques Lacan, “Remarque sur le rapport de Daniet Lagache,” in Écrits (reference note 36), of “an exclusion having its source in these signs as such being able to come about only as a condition of consistency within a chain that is to be constituted; let us also add that the one dimension limiting this condition is the translation of which such a chain is capable. Let us consider this game of lotto for just a moment more. We may then discover that it is only because these elements turn up by sheer chance within an ordinal series, in a truly unorganized way, that their appearance makes us draw lots” (p. 658). (AO, 39)

- Deleuze and Guattari refer to Lacan’s lecture Remarks on Daniel Lagache’s Presentation which can be found in Lacan’s pivotal book Écrits. For context, Daniel Lagache was a French psychoanalyst.

In this footnote, Lacan explains that exclusion is essential for the functioning of the signifying chain. The signifier gains meaning not by what it represents, but by what it excludes (e.g., “mouth” gains meaning because it is not “dog”). These exclusions establish the consistency of the chain, as the chain is structured by the relationship between signifiers.

When Lacan speaks of the translation of the chain, he highlights a key limitation: the chain can only be understood or interpreted in terms of the relations between signifiers, not as isolated, individual elements. To illustrate this, Lacan uses the lottery wheel as an example. In a lottery, balls marked with numbers (e.g., 1–50) are placed in a spinning wheel and drawn at random. While the order in which the numbers are drawn appears random (e.g., 48, 2, 18), all the numbers are part of a structured set. They are ordinally related to one another as 1 is less than 2, 2 is less than 3, and so on, with all possible relations present between the numbers; and, the lottery has specific rules. This mirrors the signifying chain, where signifiers might appear to be random but are governed by a deeper structure.

Unlike Lacan’s emphasis on the signifying chain functioning through exclusion (as referenced in this footnote), Deleuze and Guattari argue that the disjunctive synthesis is defined inclusively as they conceptualize machines not by what they can’t do but by what the machine is capable of doing. For example, the mouth-machine can function either as an eating-machine or anal-machine or talking-machine or breathing-machine and so on. Notice the “either … or … or …” in the previous sentence. The mouth-machine can take on multiple functions at once and there are multiple coexisting permutations for the capacities of the mouth-machine without imposing an “either/or” choice. In Lacan’s seminar on The Purloined Letter, which addresses repetition automatism, it becomes clear why Deleuze and Guattari utilize this seminar as the capacities of machines are functionally coded through their processes of connecting and disconnecting, emitting and interrupting flows. For instance, a mouth-machine is coded with a range of capacities (a code that delineates eating and breathing and so on) while continuously evolves through its various connections and disconnections, constantly actualizing its code.

Exclusion arises only when inhibiters or repressers intervene, limiting flows. These limitations lead to the emergence of a “personal subject,” which can be understood as a global person or fixed identity. This process reinforces the notion of a Cartesian subject, in contrast to the open, pluralistic nature of the disjunctive synthesis, which thrives on multiplicity and non-exclusionary connections.

Deleuze and Guattari continue:

No chain is homogeneous; all of them resemble, rather, a succession of characters from different alphabets in which an ideogram, a pictogram, a tiny image of an elephant passing by, or a rising sun may suddenly make its appearance. (AO, 39)

When Deleuze and Guattari state that “no chain is homogenous,” they emphasize the heterogeneous nature of these chains, which are not composed of uniform elements. Instead, the chains incorporate elements from different systems or “alphabets,” where the components within the same chain may not adhere to the same rules as others. Deleuze and Guattari illustrate this with examples such as an ideogram (a symbol representing a concept, like the Yin-Yang symbol), a pictogram (a symbol directly depicting a physical object, like a no-smoking sign), or other unexpected elements like an elephant or rising sun appearing within the same chain. They write:

In a chain that mixes together phonemes, morphemes, etc., without combining them, papa’s mustache, mama’s upraised arm, a ribbon, a little girl, a cop, a shoe suddenly turn up. (AO, 39)

- Phonemes are the smallest units of sound that distinguish one word from another. For example, “cat” and “bat” are distinguishable because of the phonemes /k/ and /b/.

- Morphemes are the smallest units of meaning which modify the meaning of words. For example, morphemes can be stand alone words like “cat” or “bat” but they can also alter the meaning in terms of prefixes, suffixes, etc. (e.g., “cat” has a different meaning than “cats.”)

The (a)signifying chains blend various parts of the smallest units of language — such as phonemes and morphemes — without reducing them to uniformity. Each element retains its distinct characteristics while remaining capable of connecting and disconnecting with other elements in the chain, all of which follow their own rules and originate from their respective “alphabets.”

Each chain captures fragments of other chains from which it “extracts” a surplus value, just as the orchid code “attracts” the figure of a wasp: both phenomena demonstrate the surplus value of a code. (AO, 39)

In this passage, the English translation places “extracts” and “attracts” in quotes, whereas the original French uses the single term tire, meaning “to draw from.” Each chain draws from fragments of other chains, neither replicating them nor remaining separate, but instead transforming the chains through each capture. Deleuze and Guattari illustrate this with the example of the orchid and the wasp: rather than existing as distinct entities, the orchid’s code draws the figure of the wasp, just as the wasp draws the figure of the orchid. In this coupling, both are fundamentally transformed. This interaction generates a surplus of code, enabling an expansion of inclusive disjunctions — connections that multiply rather than exclude.

They continue:

[The disjunctive synthesis] is an entire system of shuntings along certain tracks, and of selections by lot, that bring about partially dependent, aleatory phenomena bearing a close resemblance to a Markov chain.

(AO, 39)

Deleuze and Guattari describe the disjunctive synthesis as “an entire system of shuntings,” drawing an analogy to train routes and the levers that determine their direction. This process operates through “selections by lot,” suggesting that disjunction follows a seemingly random mechanism influenced by prior outcomes. In this sense, the path of desire is not purely random but rather shaped by past events in a way that resembles a probabilistic structure. This is similar to a Markov chain, a process in which the outcome of each event depends on the state of the previous one. A fitting example is a board game involving dice — while each roll is a matter of chance, the game’s possible trajectories are constrained by prior rolls.

Deleuze and Guattari continue:

The recordings and transmissions that have come from the internal codes, from the outside world, from one region to another of the organism, all intersect, following the endlessly ramified paths of the great disjunctive synthesis. (AO, 39)

There are two key points to highlight in this quote:

- First, Deleuze and Guattari do not use “and” when listing “internal codes,” “the outside world,” and “from one region to another of the organism,” which, at first, make these concepts appear to be synonymous. However, these are distinct concepts.

- Second, the phrase “from the outside world” is a mistranslation; the original French text actually says “du milieu extérieur” which translates to “exterior milieu.”

The flow of desire operates like a train on tracks, with each prior recording shifting the tracks for future movement — with these recordings coming from both internal codes and their exterior milieu. For example, genes function as an internal code, while the exterior milieu consists of the environmental elements specific to the lived being with those genes. The disjunctive synthesis facilitates the intersection of these codes and flows, thus producing the organism. In this quote, Deleuze and Guattari reference Chapter 1.2, where they state that the organism is the enemy of the body (a reference to Antonin Artaud).

Furthermore:

If this constitutes a system of writing, it is a writing inscribed on the very surface of the Real: a strangely polyvocal kind of writing, never a biunivocalized, linearized one; a transcursive system of writing, never a discursive one; a writing that constitutes the entire domain of the “real inorganization” of the passive syntheses, where we would search in vain for something that might be labeled the Signifier — writing that ceaselessly composes and decomposes the chains into signs that have nothing that impels them to become signifying.

(AO, 39)

If we were to conceive of the disjunctive synthesis as akin to writing, this writing is inscribed on the surface of the Real, meaning it’s not symbolic or representational in the usual sense. Instead, it’s imprinted on reality itself, structuring reality while simultaneously being structured by reality. It is described as “polyvocal” rather than “biunivocalized,” indicating that the writing is open-ended and multiple voices are at play, each conveying various meanings. In contrast, biunivocalization suggests a one-to-one correspondence, where words have fixed meanings tied to specific ideas.

When Deleuze and Guattari describe this writing as “transcursive” instead of “discursive,” they are emphasizing that this writing breaks away from normative, linear storytelling structures. Transcursive writing does not follow a fixed order or a structured progression; it moves fluidly in a non-linearized fashion. The reference to the “real inorganization” highlights that reality itself is not structured or orderly in a traditional sense — it is not governed by a preexisting system of meaning. Hence, why they first capitalize “Real” in this paragraph to discuss the Lacanian concept and move on to say “real” to signal what is actually happening. At any rate, this kind of writing does not rely on the Signifier. Instead, it is concerned with signs that are in a constant state of flux, forming and disassembling without necessarily becoming fixed or signifying in a stable way.

Deleuze and Guattari conclude this paragraph by saying:

The one vocation of the sign is to produce desire, engineering it in every direction. (AO, 39)

The sign does not signify anything. The sign produces desire.

Paragraph Five

To continue:

These chains are the locus of continual detachments — schizzes* on every hand that are valuable in and of themselves and above all must not be filled in. (AO, 39)

- *The footnote here says: “A coined word (French schize), based on the Greek verb schizsin, ‘to split,’ ‘to cleave,’ ‘to divide.’ (Translators’ note.)”

Deleuze and Guattari describe these not-so-signifying chains as “the locus of continual detachments,” emphasizing the constant process of machines detaching from one another in order to form new connections — similar to a train detaching from one track and coupling onto another. Schizzes involve these breaks and detachments, not as gaps to be filled but as productive ruptures that generates new flows. There is no fundamental lack or emptiness at the heart of these detachments.

Deleuze and Guattari write:

This is thus the second characteristic of the machine: breaks that are a detachment (coupures-détachements), which must not be confused with breaks that are a slicing off (coupures-prélevèments). (AO, 39)

At the start of this section, we saw that the first characteristic of a machine resembles a ham-slicing machine, where machines cut into material flows — this corresponds to the first synthesis. In the second synthesis, the machine’s defining feature is their breaks and detachments. These two characteristics should not be conflated:

The latter have to do with continuous fluxes and are related to partial objects. (AO, 39)

The breaks involved with slicing and cutting into material flows are linked to partial objects. However, with the second characteristic, we encounter something different:

Schizzes have to do with heterogeneous chains, and as their basic unit use detachable segments or mobile stocks resembling building blocks or flying bricks. (AO, 39–40)

Here, Deleuze and Guattari describe the second characteristic, which pertains to a heterogeneous chain, resembling bricks that can be used to construct various structures. They write:

We must conceive of each brick as having been launched from a distance and as being composed of heterogeneous elements: containing within it not only an inscription with signs from different alphabets, but also various figures, plus one or several straws, and perhaps a corpse. (AO, 40)

Each of these building blocks, according to Deleuze and Guattari, comes from a long distance, having been connected to and detached from various machines. When they describe these bricks as composed of heterogeneous elements, they are illustrating how these blocks carry a variety of signs from different sources — alphabets, syntax, figures, morphemes, and phonemes. The “straws” they mention can be understood as small, seemingly insignificant components that contribute to the larger structure, highlighting the complexity and diversity of elements involved. The reference to a corpse seems to evoke some kind of vitality — potentiality a reference to how desire desires its own death.

Deleuze and Guattari conclude this paragraph by writing:

Cutting into the flows (le prélevèment sur du flux) involves detachment of something from a chain; and the partial objects of production presuppose stocks of material or recording bricks within the coexistence and the interaction of all the syntheses. (AO, 40)

They describe how machines cut into the flows, leading to the detachment of an element from a chain. This detachment should not be understood as a gap or void, but rather as a reconfiguration that opens up possibilities for new connections. The partial objects in the production process rely on a stock or pre-existing reserve of “recording bricks,” which facilitates the intersection of internal codes with their external milieus. Ultimately, this process is not isolated but is interconnected with other syntheses of production, highlighting the interdependence of these syntheses.

Paragraph Six

Deleuze and Guattari continue by positing a question:

How could part of a flow be drawn off without a fragmentary detachment taking place within the code that comes to inform the flow? (AO, 40)

This question asks how it is possible for a flow to be drawn off without rupturing the code that informs and governs that very flow. They write:

When we noted a moment ago that the schizo is at the very limit of the decoded flows of desire, we meant that [the schizo] was at the very limit of the social codes, where a despotic Signifier destroys all the chains, linearizes them, biunivocalizes them, and uses the bricks as so many immobile units for the construction of an imperial Great Wall of China.

(AO, 40)

In this quote, Deleuze and Guattari reference Chapter 1.4, where they explain how the schizo arises from decoded flows of desire. The schizo dismantles the socius but encounters resistance from the despotic Signifier, which defines itself exclusively — in opposition to what it is not. This Signifier enforces a uniform, singular chain by destroying the multiplicity of chains by replacing them with a rigid, universal structure. In doing so, it biunivocalizes meaning — reducing each sign to a fixed, one-to-one correspondence. This process is compared to building a Great Wall of China, a rigid and unyielding structure that restricts and confines the free flow of desire.

They write:

But the schizo continually detaches them, continually works them loose and carries them off in every direction in order to create a new polyvocity that is the code of desire. (AO, 40)

Amidst the despotic Signifier’s resistance, which repetitively records and codes desire in a way that fixes meaning biunivocally (via a one-to-one correspondence), the schizo remains in a perpetual process of detaching codes and dispersing them in multiple directions, generating a polyvocity of meanings — or rather, a code of desire. Deleuze and Guattari continue:

Every composition, and also every decomposition, uses mobile bricks as the basic unit. (AO, 40)

Regardless of how the code is structured — whether it is being biunivocalized or polyvocalized — there exist “mobile bricks” or elements within the chain, be they morphemes, phonemes, an image of an element or a rising sun, a guttural sound, or anything else. These fundamental units are building blocks — used to construct or deconstruct the structure of codes.

To continue:

Diaschisis and diaspasis, as Monakow put it: either a lesion spreads along fibers that link it to other regions and thus gives rise at a distance to phenomena that are incomprehensible from a purely mechanistic (but not a machinic) point of view; or else a humoral disturbance brings on a shift in nervous energy and creates broken, fragmented paths within the sphere of instincts. (AO, 40)

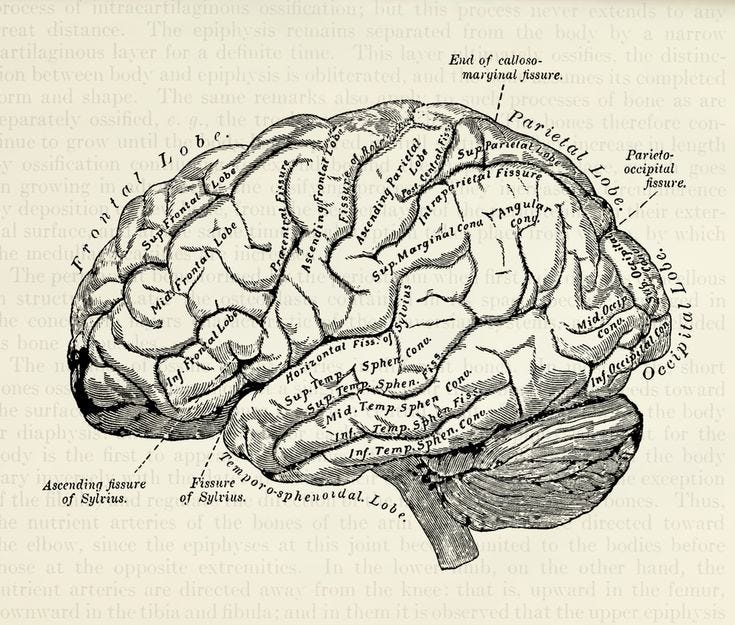

Deleuze and Guattari reference Constantin von Monakow, a Russian-Swiss neuropsychologist concerned with neurological disruptions such as diaschisis and diaspasis. To fully grasp their argument, we first need to define these concepts:

- Diaschisis: A phenomenon in which damage to one area of the brain affects distant regions, disrupting their function.

- Diaspasis: A phenomenon where energy is redirected in an unpredictable manner — such as through trauma — causing flows to fragment and instinctual behaviors to change.

From a mechanistic perspective, these disruptions are seen as system failures that require repair. However, Deleuze and Guattari take a machinic approach, arguing that such disruptions create new connections and pathways for desire to flow.

Furthermore:

These bricks or blocks are the essential parts of desiring-machines from the point of view of the recording process: they are at once component parts and products of the process of decomposition that are spatially localized only at certain moments, by contrast with the nervous system, which is a great chronogeneous machine: a melody-producing machine of the “music box” type, with a nonspatial localization.* (AO, 40)

- This quote references Constantin von Monakow and Raoul Mourgue’s Introduction biologique à l’étude de la neurologie et de la psychopathologie, intégration et désintégration de la fonction published in 1928.

- The notion of “localization” will be explained shortly when Deleuze and Guattari criticize Jacksonist philosophy.

- The words “by contrast” do not appear in the French. Instead, the French addition roughly translates to “in relation to.” This is extremely important and an error on behalf of the English translation. Desiring-machines are not opposed to the nervous system.

To reiterate: these “building blocks” are necessary for the recording process. Desiring-machines function by breaking down, where their components (building blocks) serve as structural parts that compose the structure as well as decompose the structure (by establishing new connections that form other structures and so on). Deleuze and Guattari relate this to the nervous system, which they call a “great chronogeneous machine” — a machine that operates through temporality (chrono-) rather than spatial fragmentation through attachment and detachment. To clarify, the nervous system functions through temporal and energetic redirections — where disturbances and ruptures such as diaschisis and diaspasis alter the timing of signals and pathways. Like how a brain lesion affects another part side of the brain unpredictably, the fundamental question is about how flows of desire are redirected and the new pathways that emerge. Deleuze and Guattari compare the nervous system to a music box that produces a melody when the notes are hit at a specific time. Altering or rupturing the notes changes the timing between notes and the overall melody that emerges.

They elaborate:

What makes Monakow and Mourgue’s study an unparalleled one, going far beyond the entire Jacksonist philosophy that originally inspired it, is the theory of bricks or blocks, their detachment and fragmentation, and above all what such a theory presupposes: the introduction of desire into neurology. (AO, 40)

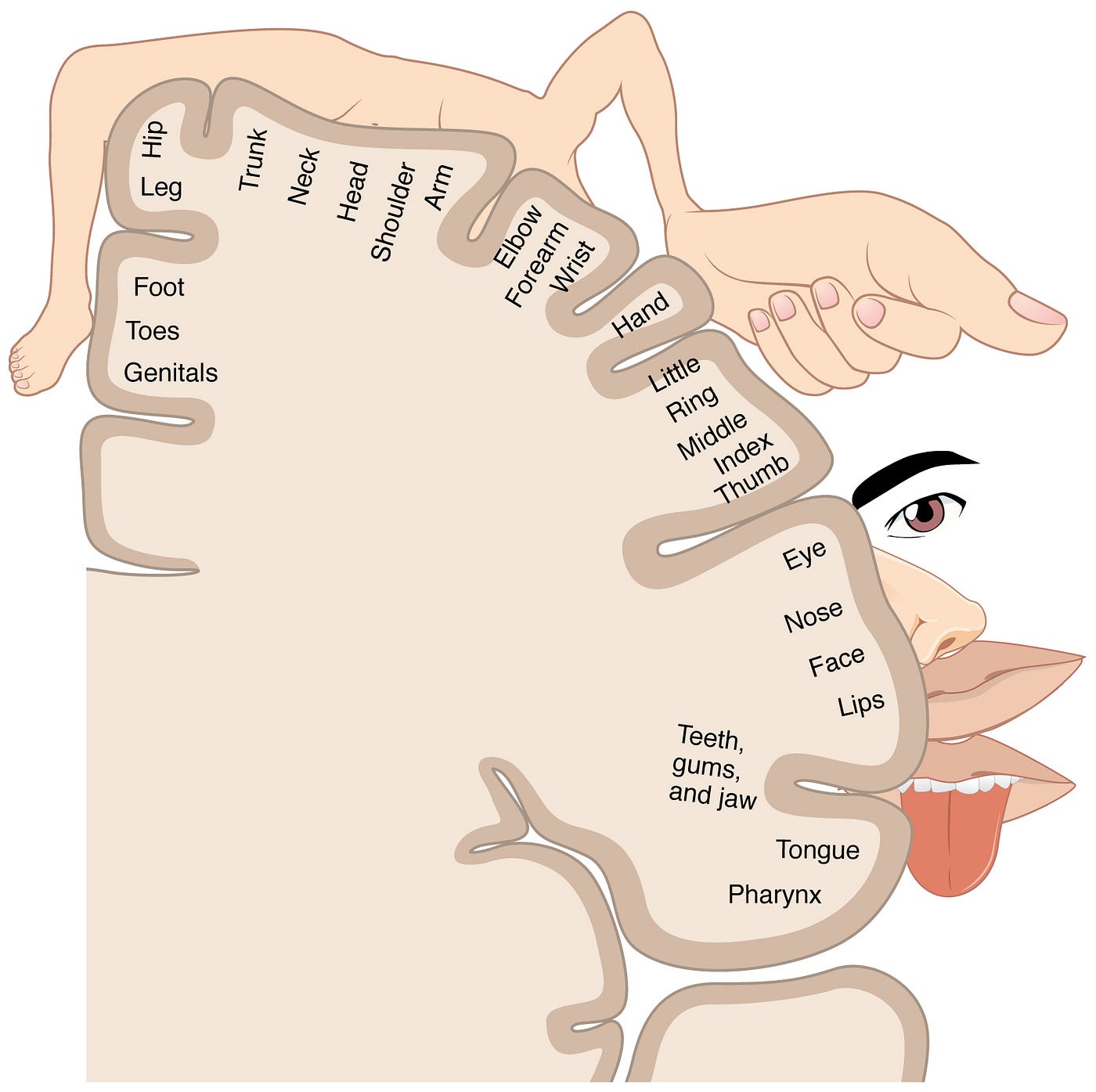

Deleuze and Guattari praise Monakow and Mourge for departing from Jacksonist philosophy, which is based on the ideas of English neurologist John Hughlings Jackson. Jackson’s model envisions the nervous system as a hierarchical structure in which higher cortical regions, such as the cortex, regulate instinctual responses. If these higher regions are damaged, the lower levels become disinhibited, leading to primitive and uncontrolled functions.

Jackson observed epilepsy patients where he noticed that seizures often progressed predictably from one part of the body to another (face → arm → hand), a phenomenon known as the Jacksonian march. This led Jackson to conceive of the brain having a type of somatotopic organization of the brain where the brain is deemed a top-down system with the body being mapped onto the brain—a model known as the cortical homunculus. When Deleuze and Guattari referenced ‘nonspatial localization’ earlier, they were drawing from Monakow and Mourge who moved beyond Jackson’s functional localization — the idea that brain functions are tied to specific spatial regions. Deleuze and Guattari expand upon Monakow and Mourge while criticizing the spatial localization that Jacksonist philosophy denotes to the nervous system. Instead, Deleuze and Guattari conceptualize the nervous system as nonspatially localized; for them, it is a question of the speed and rate of signals and the path to their intended destination.

Monakow and Mourge’s work is revolutionary for integrating the concept of desire into neurology.

Production of Consumption / Conjunctive Synthesis

Paragraph Seven

Deleuze and Guattari introduce the third kind of break — the one that defines the production of consumption:

The third type of interruption or break characteristic of the desiring-machine is the residual break (coupure-reste) or residuum, which produces a subject alongside the machine, functioning as a part adjacent to the machine. (AO, 40)

The residual break — also known as residuum — is responsible for producing that subject that exists on the periphery of desiring-machines. The subject never identifies with desiring-machines, but rather traverses the body without organs and oscillates between circles that converge on desiring-machines. Deleuze and Guattari write:

And if this subject has no specific or personal identity, if it traverses the body without organs without destroying its indifference, it is because it is not only a part that is peripheral to the machine, but also a part that is itself divided into parts that correspond to the detachments from the chain (détachements de chaine) and the removals from the flow (prélevèments de flux) brought about by the machine.

(AO, 40–41)

This subject is unfixed and, as a result, does not impose a rigid structure upon the body without organs — it remains in a state of indifference. Not only does it exist at the periphery of desiring-machines, but it is itself a fragmented, divided into multiple parts that correspond to the breaks produced by the first and second syntheses. The first synthesis operates through cuts akin to a ham-slicing machine, removing segments from a flow (prélèvement de flux). The second synthesis introduces breaks that function as detachments (détachements de chaine). The subject that emerges in the third synthesis is composed of these fragmented parts, shaped by the interruptions that constitute it.

Thus this subject consumes and consummates each of the states through which it passes, and is born of each of them anew, continuously emerging from them as a part made up of parts, each one of which completely fills up the body without organs in the space of an instant. (AO, 41)

As mentioned in Chapter 1.3, the subject continuously undergoes a cycle of dying and rebirth by consuming the states it experiences. It is perpetually produced through its passing of states. Deleuze and Guattari describe this subject as a “part made up of parts” to avoid placing it at the center of analysis. All of these parts are necessary to fill the body without organs. They continue by discussing Lacan:

This is what allows Lacan to postulate and describe in detail an interplay of elements that is more machinic than etymological: parere: to procure; separare: to separate; se parere: to engender oneself. (AO, 41)

Deleuze and Guattari praise Lacan for framing the interplay of drives (desiring-machines) in a machinic rather than purely etymological way. The terms parere, separare, and se parere share grammatical similarities in their suffixes. Ironically, despite Lacan’s linguistic focus, Deleuze and Guattari suggest that his treatment of drives operates machinically rather than etymologically. By referencing these Lacanian terms — parere, separare, and se parere — they highlight the three syntheses: procuring (to produce) corresponds to the connective synthesis, separating or detaching aligns with the disjunctive synthesis, and the notion of engendering oneself marks the emergence of the subject in the third synthesis.

Yet, even though Lacan describes elements in a machinic manner, he centers the subject as a part divorced from the whole:

At the same time [Lacan] points out the intensive nature of this interplay: the part has nothing to do with the whole;

“it performs its role all by itself. In this case, only after the subject has partitioned itself does it proceed to its parturition . . . that is why the subject can procure what is of particular concern to it here, a state that we would label a legitimate status within society. Nothing in the life of any subject would sacrifice a very large part of its interests.”

(AO, 41)

This quote comes from Lacan’s Position of the Unconscious, a text based on his remarks at the 1960 Bonneval Colloquium, later included in Écrits. While Lacan initially frames these elements in a machinic manner, he ultimately missteps by treating them as entirely separate from the whole, as if they exist in isolation.

(Spoiler: Chapter 1.6 is titled “The Whole and Its Parts” which will directly critique this line of thinking.)

Paragraph Eight

Akin to the other syntheses, the break found in the third synthesis does not assume deficiency:

Like all the other breaks, the subjective break is not at all an indication of a lack or need (manque), but on the contrary a share that falls to the subject as a part of a whole, income that comes its way as something left over. (AO, 41)

The residual break — the break that produces the subject — does not indicate lack, need, or acquiescence, some kind of lost object. This break is that of an excess that falls to the subject — an excess of energy from the previous synthesis where Numen gets transformed into Voluptas.

There is no break that indicates lack:

(Here again, how bad a model the Oedipal model of castration is!)

(AO, 41)

Within the Oedipal model of castration, psychoanalysis positions the phallus within a framework of acquiescence — something the subject lacks. However, when examining the three syntheses, it becomes clear that these breaks are not fundamentally rooted in lack. The Oedipal model of castration is not an a priori structure but rather something erroneously produced.

There is no break that indicates lack:

That is because breaks or interruptions are not the result of an analysis; rather, in and of themselves, they are syntheses. (AO, 41)

All of these breaks and interruptions are part of the real — or rather, they produce the real. Each synthesis is defined by breaks and interruptions, which are constitutive of the syntheses themselves. These ruptures are not secondary effects but integral to the process of production that produces reality. Furthermore:

Syntheses produce divisions. (AO, 41)

It must be noted that the three syntheses occur simultaneously — Deleuze and Guattari are not describing separate stages but three aspects of the same process. Each synthesis, however, carries its own distinct kind of break:

Let us consider, for example, the milk the baby throws up when it burps; it is at one and the same time the restitution of something that has been levied from the associative flux (restitution de prélevèment sur le flux associatif); the reproduction of the process of detachment from the signifying chain (reproduction de détachement sur la chaine signifiante); and a residuum (résidu) that constitutes the subject’s share of the whole.

(AO, 41)

In the example of a baby throwing up milk, the three syntheses are present…

- Connective Synthesis: The mouth-machine cuts off a digestive flow.

- Disjunctive Synthesis: The mouth-machine takes on a different capacity, detaching from the function of eating or breathing or speaking.

- Conjunctive Synthesis: Subjectivity emerges from this process, with the subject potentially experiencing relief or discomfort.

Deleuze and Guattari write:

The desiring-machine is not a metaphor; it is what interrupts and is interrupted in accordance with these three modes. (AO, 41)

As stated in the opening lines of the text, desiring-machines are literal machines. Desiring-machines interrupt and are interrupted in accordance to the three syntheses. To clarify the different energies and breaks present in each synthesis, Deleuze and Guattari write:

The first mode has to do with the connective synthesis, and mobilizes libido as withdrawal energy (énergie de prélevèment).

The second has to do with the disjunctive synthesis, and mobilizes the Numen as detachment energy (énergie de détachement) .

The third has to do with the conjunctive synthesis, and mobilizes Voluptas as residual energy (énergie résiduelle).

(AO, 41)

Deleuze and Guattari offer a succinct summary: as each synthesis transitions into the next, the forms of energy undergo transformation — libido becomes Numen, and Numen becomes Voluptas. As Deleuze and Guattari conclude this section, they remind the readers that the three syntheses compose the process of production:

It is these three aspects that make the process of desiring-production at once the production of production, the production of recording, and the production of consumption. (AO, 41)

Thus:

To withdraw a part from the whole, to detach, to “have something left over,” is to produce, and to carry out real operations of desire in the material world. (AO, 41)

It is clear that these breaks — whether through withdrawal, detachment, or residue — do not signify lack or acquiescence. Rather, they are integral to the process of production itself. This is what constitutes the production of reality itself.

— —

Citations: