In Chapter 1.1, 1.2, and 1.3, we find a detailed analysis of the three syntheses of the unconscious. At this point, it is evident that Deleuze and Guattari are criticizing the rigidity of psychiatric institutions.

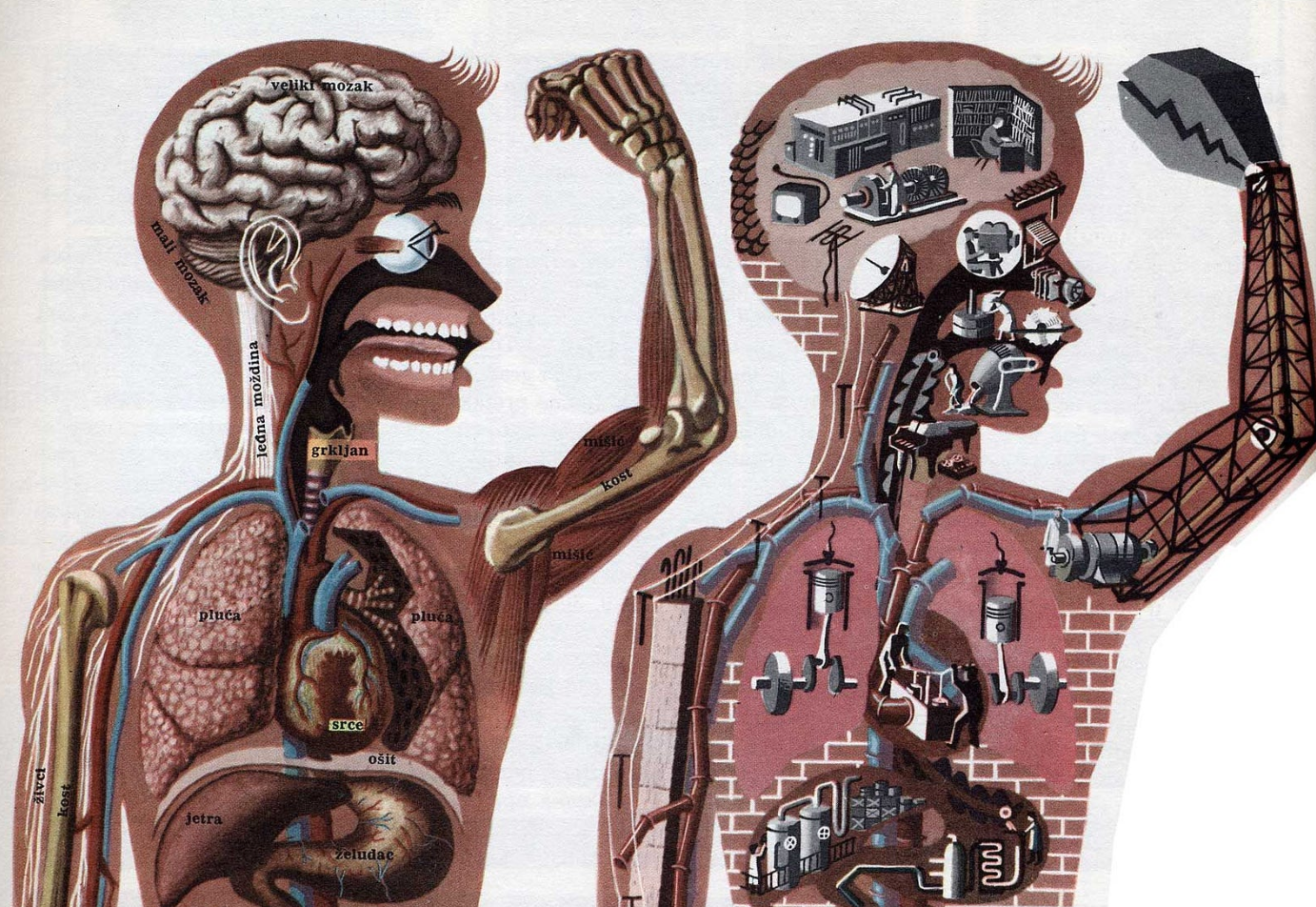

In this section, Deleuze and Guattari are going to highlight their materialist psychiatry which serve as a set of practices in opposition to the psychiatric model.

Note 1: I will constantly be revising this blog post in order to do a line-by-line interpretation of the text.

**Citation Note: Full citation provided at the end of this post

Paragraph One

Deleuze and Guattari begin by reaffirming their earlier thesis concerning delirium:

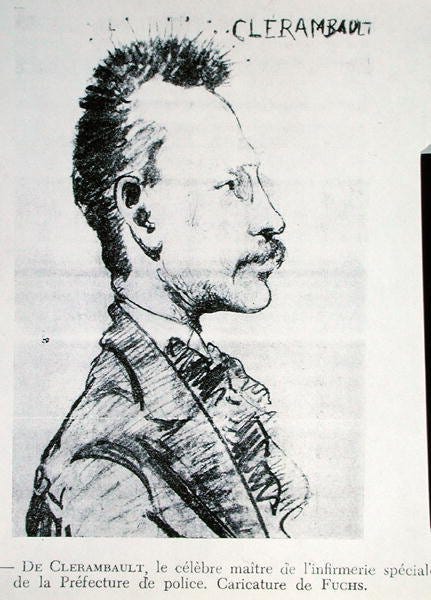

The famous hypothesis put forward by the psychiatrist G. de Clerambault seems well founded: delirium, which is by nature global and systematic, is a secondary phenomenon, a consequence of partial and local automatistic phenomena. (AO, 22)

They reference French psychiatrist Gatian de Clérambault who considers delirium to be a secondary phenomenon. As noted in Chapter 1.3, for Schreber to declare that he is becoming a woman, he must first internalize the delirium. This process depends on the delirious nature of what defines a woman. Whatever constitutes the concept of a woman — whatever ‘woman’ even means — must exist prior to the delirium in the form of affections upon Schreber’s body without organs.

Although the concept of woman is portrayed as a delirious notion above, it’s important to recognize that this is a form of collective delirium (i.e., the category of woman is a social construction). While Deleuze and Guattari don’t elaborate much on the broader implications of delirium in this passage, one can draw from Deleuze’s works Empiricism and Subjectivity and Two Regimes of Madness to assert that delirium is essentially imagination itself. In other words, delirium is a secondary phenomenon that does not strictly adhere to a linear path of recording; instead, delirium diverges from the path of recording. If this divergence becomes significant enough to create a bifurcation, it is referred to as schizophrenia.

For the sake of clarity, let’s briefly discuss schizophrenia. In Anti-Oedipus, schizophrenia is understood in two distinct ways. First, there is schizophrenia as a clinical condition, which is highlighted in the sixth paragraph of this section. In this case, schizophrenia is interrupted or put into the context of an end goal; these are the people found in mental institutions. Second, there is schizophrenia as the process of production. Capitalism produces this schizophrenic subject as the result of decoded and deterritorialized flows of desire, which is highlighted in the final few paragraphs of this section. In the first case — the case of the clinical entity — schizophrenia as a process of decoding and deterritorialization becomes interrupted or turned into an end goal where schizophrenia is divorced from its processual nature. In the second case, schizophrenia serves as a process in a state of becoming. Regardless, delirium is especially important in the context of all cases of schizophrenia because it represents a departure from an established path of recording. The difference between schizophrenia as a clinical condition and schizophrenia as a process of decoding and deterritorialization lies in the degree to which this delirium manifests.

Deleuze and Guattari continue:

Delirium is in fact characteristic of the recording that is made of the process of production of the desiring-machines; and though there are syntheses and disorders (affections) that are peculiar to this recording process, as we see in paranoia and even in the paranoid forms of schizophrenia, it does not constitute an autonomous sphere, for it depends on the functioning and the breakdowns of desiring-machines. (AO, 22)

To clarify, Deleuze and Guattari are reiterating their earlier claim that nothing is independent of the production process, specifically the production of recording. They argue that there are specific affections — or particular ways the body experiences certain phenomena — that can appear atypical within this recording process. For example, Deleuze and Guattari reference paranoid forms of schizophrenia, such as a paranoid schizophrenic believing that someone intends to harm them, even if no such threat exists. However, it’s important to emphasize that these beliefs, thoughts, or affections do not exist in isolation; they are not part of an autonomous sphere. Paranoid schizophrenia and the deliriums associated with it are secondary to the recording process itself. It is contingent upon the functioning and breakdown of desiring-machines, meaning that all these phenomena are interconnected and dependent upon the process of production.

Regardless, Deleuze and Guattari continue by examining Clerambault’s arguments pertaining to delirium:

Nonetheless Clerambault used the term “(mental) automatism” to designate only athematic phenomena — echolalia, the uttering of odd sounds, or sudden irrational outbursts — which he attributed to the mechanical effects of infections or intoxications. (AO, 22)

Clerambault’s utilization of the term ‘(mental) automatism’ to describe athematic phenomena reflects his belief that behaviors considered nonsensical, such as the repetition of words, the utterance of strange sounds, or ‘irrational outbursts,’ are akin to mechanical effects, similar to those resulting from infections or intoxications (e.g., diseases, drugs, alcohol, etc.). In this manner, Clerambault finds these behaviors to be isolated incidents rather than a secondary result of the functioning and breakdown of desiring-machines.

Deleuze and Guattari summarize Clerambault’s main argument succinctly:

Moreover, [Clerambault] explained a large part of delirium in turn as an effect of automatism; as for the rest of it, the “personal” part, in his view it was of the nature of a reaction and had to do with “character,” the manifestations of which might well precede the automatism (as in the paranoiac character, for instance). (AO, 22)

Deleuze and Guattari are referring to Clerambault’s writings found in Oeuvre psychiatrique, which were first published in 1942 (and later fully published posthumously in 1981). In these texts, Clerambault identifies two key aspects of delirium. First, he views delirium as resulting from automatism, suggesting that certain responses or behaviors are automatic and caused by physical conditions like infections or intoxications. Second, he posits that the remaining aspects of delirium are linked to an individual’s character, why may influence of precede these automatic responses.

So … what’s the difference between Clerambault’s perspective on delirium and that of Deleuze and Guattari? Deleuze and Guattari write:

Hence Clerambault regarded automatism as merely a neurological mechanism in the most general sense of the word, rather than a process of economic production involving desiring-machines.

(AO, 22; emphasis mine)

Evidently, Deleuze and Guattari criticize Clerambault’s approach to history in relation to his psychiatric theories:

As for history, [Clerambault] was content merely to mention its innate or acquired nature. (AO, 22)

Clerambault’s brief mention of history is insufficient for Dleuze and Guattari. Clerambault considers history to be either innate (inherent from birth), acquired (shaped by one’s character), or a combination of both. However, Deleuze and Guattari critique this view for being overly reductive. Clerambault emphasizes automatism and treats experiences as isolated rather than part and parcel with the sociohistorical field.

Unfortunately for Clerambault, Deleuze and Guattari regard him similarly to how Karl Marx regarded the German philosopher Ludwig Feuerbach:

Clerambault is the Feuerbach of psychiatry, in the sense in which Marx remarks: “Whenever Feuerbach looks at things as a materialist, there is no history in his works, and whenever he takes history into account, he no longer is a materialist.” (AO, 22; emphasis mine)

In this quote, Deleuze and Guattari are directly referencing Marx’s Theses on Feuerbach, written in 1845 and published in 1888. Although Marx acknowledged some of Feuerbach’s insights as noteworthy — particularly Feuerbach’s focus on material conditions — he criticized Feuerbach for being overly reductive. Marx found Feuerbach’s analysis to lack consideration of how these material conditions are shaped by historical and social relations. Deleuze and Guattari employ Marx’s criticisms of Feuerbach in order to draw a parallel to Clerambault; as they state, “Clerambault is the Feuerbach of psychiatry.”

As Clerambault’s psychiatry lacked a conceptualization of the sociohistorical, Deleuze and Guattari posit was a true materialist psychiatry looks like:

A truly materialist psychiatry can be defined, on the contrary, by the twofold task it sets itself: introducing desire into the mechanism, and introducing production into desire. (AO, 22)

We will soon learn the extent of what Deleuze and Guattari’s materialist psychiatry has to offer, but we must continue.

Paragraph Two

At any rate, Deleuze and Guattari continue by calling out false forms of materialism for what it is:

There is no very great difference between false materialism and typical forms of idealism. (AO, 22; emphasis mine)

To reach this conclusion, Deleuze and Guattari examine how schizophrenia has been formally theorized and how it has been confined within a simplistic, reductive trinary framework. They argue that the normative understanding of schizophrenia has manifested itself as a false materialism, which ultimately resembles a conventional form of idealism, detached from the material realities that produce it. Deleuze and Guattari write:

The theory of schizophrenia is formulated in terms of three concepts that constitute its trinary schema: dissociation (Kraepelin), autism (Bleuler), and space-time or being-in-the-world (Binswanger). (AO, 22)

Let’s review each of these concepts and thinkers associated with them:

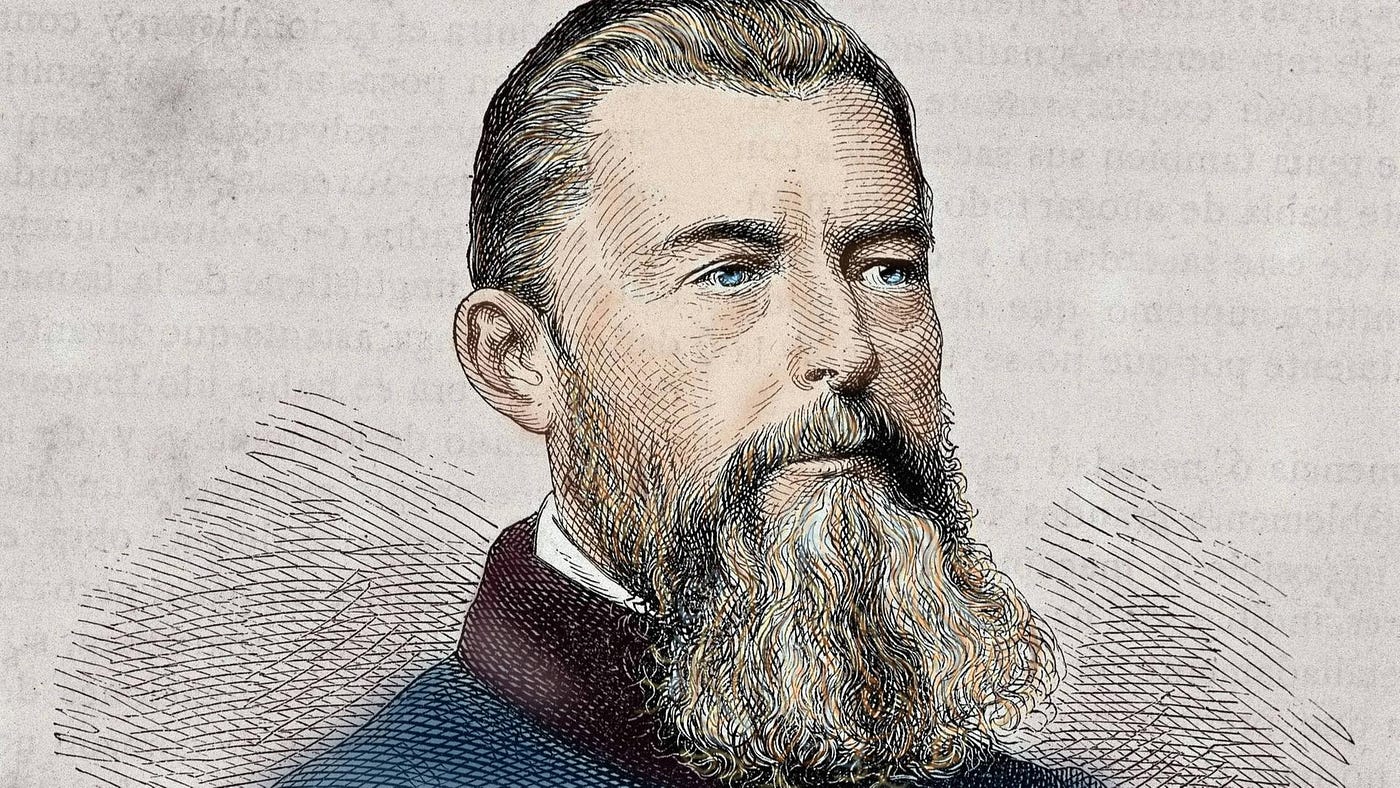

Dissociation (Kraepelin)

German psychiatrist, Emil Kraepelin, was a pioneering figure in the classification of mental illnesses. He introduced the concept of “dementia praecox,” an early classification that later evolved into the modern understanding of schizophrenia. Kraepelin’s classification system distinguished between different forms of psychosis, including manic-depression (now known as bipolar disorder) and dementia praecox. Although Kraepelin did not use the term “schizophrenia” (which was introduced later by Eugen Bleuler, whom we will get to shortly), his work laid the foundation for modern psychiatric classification.

Following the quote above — Deleuze and Guattari write:

[Kraepelin’s concept] is an explanatory concept that supposedly locates the specific dysfunction or primary deficiency. (AO, 22)

Essentially, Kraepelin introduced the concept of dissociation to explain dementia praecox, proposing that the disorder was rooted in a specific dysfunction or deficiency, which he largely understood to be a biological impairment.

Autism (Bleuler)

Swiss psychiatrist, Eugen Bleuler, introduced the term “schizophrenia” to replace “demential praecox,” critiquing Kraepelin’s concept for its narrow focus. Kraepelin viewed dementia praecox as a progressive disorder that inevitably worsened over time. In contrast, Bleuler offered a broader perspective, acknowledging degrees of impairment and recognizing a wider range of behaviors. He introduced the concept of “autism” as a symptom of schizophrenia, which, in his usage, referred to a literal, etymological sense of the word: autism as being closed off or detached from reality. To be clear, this is much different from contemporary understandings of autism.

Deleuze and Guattari state:

[Bleuler’s concept] is an ideational concept indicating the specific nature of the effect of the disorder: the delirium itself or the complete withdrawal from the outside world, “the detachment from reality, accompanied by a relative or an absolute predominance of [the schizophrenic’s] inner life.” (AO, 22–23)

The sentenced cited by Deleuze and Guattari above (though not cited in Anti-Oedipus) derives from Bleuler’s work Dementia Praecox or the Group of Schizophrenias, published in 1911. Bleuler’s perspective on schizophrenia emphasizes the notion of individuals being closed off from the outside world or detached from reality. While there may be variations in how this detachment manifests in each individual, Bleuler consistently views this detachment from reality as a core feature of the disorder.

Space-time or being-in-the-world (Binswanger)

Swiss psychiatrist, Ludwig Binswanger, was concerned with how individuals with schizophrenia interacted with and perceived their environment. Binswanger is recognized as a key figure in existential psychology, a field that emphasizes an individual’s personal relationship with their surroundings and their subjective experience of reality. His seminal work, Being-in-the-world, published in 1963, explores and describes how schizophrenics relate to spatial and temporal dimensions.

Deleuze and Guattari explain:

[Binswanger’s] concept is a descriptive one, discovering or rediscovering the delirious person in his own specific world. (AO, 23)

Rather than providing an explanatory reason for schizophrenia, Binswanger was concerned with the lived experience of schizophrenia.

What is common between these three concepts and thinkers?

Though Kraepelin, Bleuler, and Binswanger differ in how they conceptualize schizophrenia, they all have one thing in common: the ego.

Deleuze and Guattari state their overarching criticism of these thinkers:

What is common to these three concepts is the fact that they all relate the problem of schizophrenia to the ego through the intermediary of the “body image” — the final avatar of the soul, a vague conjoining of the requirements of spiritualism and positivism. (AO, 23)

These theorists fall short by conceptualizing schizophrenia solely as an individual pathology. Deleuze and Guattari’s critique focuses on the assumption that a coherent self exists beneath schizophrenia and that this self can be discovered by overcoming the disorder. They argue that schizophrenia should be understood in the context of sociohistorical conditions, rather than through an idealized concept of the body and its expected functions.

Paragraph Three

Deleuze and Guattari assert that the schizo fails to believe in the ego:

The ego, however, is like daddy-mommy: the schizo has long since ceased to believe in it. [The schizo] is somewhere else, beyond or behind or below these problems, rather than immersed in them. (AO, 23)

However, this is not to imply that the schizo does not face their own set of challenges. Deleuze and Guattari emphasize this point while questioning the peculiar and persistent urge to make the schizo conform to the very problems they have managed to avoid. Why insist on making the schizo confront the issues of mommy and daddy when they have already escaped the issues of mommy and daddy? They write:

And wherever [the schizo] is, there are problems, insurmountable sufferings, unbearable needs. But why try to bring [the schizo] back to what [the schizo] has escaped from, why set [the schizo] back down amid problems that are no longer problems to [the schizo], why mock his truth by believing that we have paid it its due by merely figuratively taking our hats off to it? (AO, 23)

As stated in the second paragraph of Chapter 1.4, psychoanalysts are concerned “relat[ing] the problem of schizophrenia to the ego through the intermediary of the ‘body image’” (AO, 23). Deleuze and Guattari respond to this from the perspective of the schizo:

There are those who will maintain that the schizo is incapable of uttering the word I, and that we must restore his ability to pronounce this hallowed word. All of which the schizo sums up by saying: they’re fucking me over again. (AO, 23)

Regarding the schizo being marginalized (or rather, the schizo being ‘fucked over’), Deleuze and Guattari refer to Irish novelist Samuel Beckett’s 1953 novel, The Unnamable:

“I won’t say I any more, I’ll never utter the word again; it’s just too damn stupid. Every time I hear it, I’ll use the third person instead, if I happen to remember to. If it amuses them. And it won’t make one bit of difference.” (AO, 23)

Thus, although the the schizo says “I”, this “I” is fundamentally divorced from the Cartesian “I”:

And if [the schizo] does chance to utter the word I again, that won’t make any difference either. [The schizo] is too far removed from these problems, too far past them. (AO, 23)

Paragraph Four

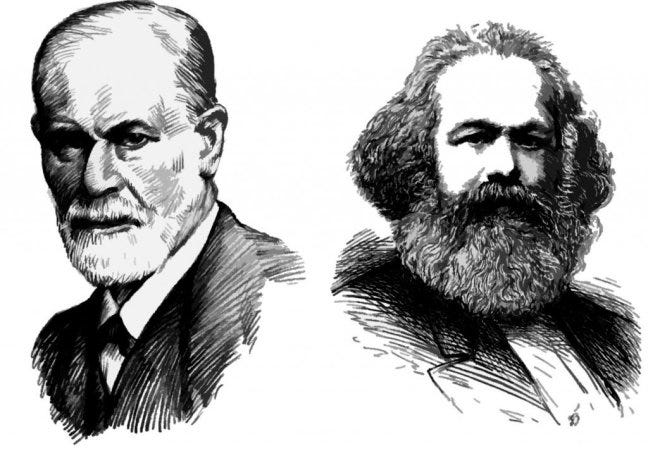

As the book’s title suggests, Anti-Oedipus seeks to deconstruct Sigmund Freud’s Oedipus complex which reduces the ego to these limited perspectives. Deleuze and Guattari write:

Even Freud never went beyond this narrow and limited conception of the ego. (AO, 23)

It’s not that Freud lacked the ability to go beyond this limited conception of the ego; rather, his own propagation of the Oedipus complex restricted him from from moving beyond this limited conception of the ego:

And what prevented him from doing so was his own tripartite formula — the Oedipal, neurotic one: daddy-mommy-me. (AO, 23)

By restricting desire to the rigid framework of daddy-mommy-me, Freud was unable to envision desire outside of this structure. Furthermore, we might as well question the relationship Freud’s Oedipus complex has to the erroneous conceptualization of autism and schizophrenia theorized by Kraepelin and Bleuler:

We may well ponder the possibility that the analytic imperialism of the Oedipus complex led Freud to rediscover, and to lend all the weight of his authority to, the unfortunate misapplication of the concept of autism to schizophrenia. (AO, 23)

Regardless, Deleuze and Guattari make clear that Freud’s project polices schizophrenia:

For we must not delude ourselves: Freud doesn’t like schizophrenics. He doesn’t like their resistance to being oedipalized, and tends to treat them more or less as animals. (AO, 23; emphasis mine)

Freud’s harsh treatment of schizophrenics stems from his belief in a normative subject capable of achieving transference. Anyone who falls outside of this established norm is subject to punishment:

They mistake words for things, he says. They are apathetic, narcissistic, cut off from reality, incapable of achieving transference; they resemble philosophers — “an undesirable resemblance.”

(AO, 23; emphasis mine)

Before analyzing this quote, it’s important to examine the two references to Freud.

- First, when Deleuze and Guattari note that Freud claims thee schizophrenic “mistake[s] words for things,” they are drawing from Freud’s The Unconscious, an essay published in 1915. Freud writes:

If we ask ourselves what it is that gives the character of strangeness to the substitutive formation and the symptom in schizophrenia, we eventually come to realize that it is the predominance of what has to do with words over what has to do with things. (The Unconscious; emphasis mine)

- Second, the phrase “an undesirable resemblance” is an unattributed citation; however, like the previous reference, it refers to Freud’s essay The Unconscious, where he states:

When we think in abstractions there is a danger that we may neglect the relations of words to unconscious thing-presentations, and it must be confessed that the expression and content of our philosophizing then begins to acquire an unwelcome resemblance to the mode of operation of schizophrenics. (The Unconscious; emphasis mine)

Now, let us get back to Anti-Oedipus:

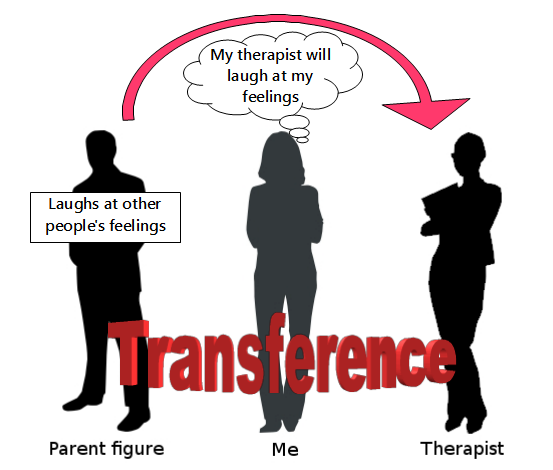

In the previous quote from Anti-Oedipus, Deleuze and Guattari explain how Freud identifies a commonality between schizophrenics and philosophers, noting an “undesirable resemblance” between them, likening them to animals. This is because Freud views the schizophrenic as incapable of transference. In psychoanalytic theory, transference refers to the process by which an analysand redirects their unconscious childhood feelings and desires onto a new object, typically the therapist or psychoanalyst.

But why is transference necessary for normative subjectivity in the first place?

Paragraph Five

Deleuze and Guattari continue by addressing the analytical challenge in psychoanalysis:

The question as to how to deal analytically with the relationship between drives (pulsions) and symptoms, between the symbol and what is symbolized, has arisen again and again. (AO, 23)

On this point, they posit a few rhetorical questions:

Is this relationship to be considered causal? Or is it a relationship of comprehension? A mode of expression? (AO, 23–24)

However, we must first consider whether the initial question about how we analytically approach the relationship between drives and symptoms is even a valid starting point. Deleuze and Guattari find this analytical challenge in psychoanalysis to be too reductive:

The question, however, has been posed too theoretically. The fact is, from the moment that we are placed within the framework of Oedipus — from the moment that we are measured in terms of Oedipus — the cards are stacked against us, and the only real relationship, that of production, has been done away with. (AO, 24)

A well-known saying attributed to psychologist Abraham Maslow is relevant to this discussion: “If the only tool you have is a hammer, it is tempting to treat everything as if it were a nail.”

When forced within the confines of Oedipus, we have already lost.

This is not to suggest that psychoanalysis has made no significant discoveries. In fact, Deleuze and Guattari acknowledge that psychoanalysis disovered the existence of the unconscious:

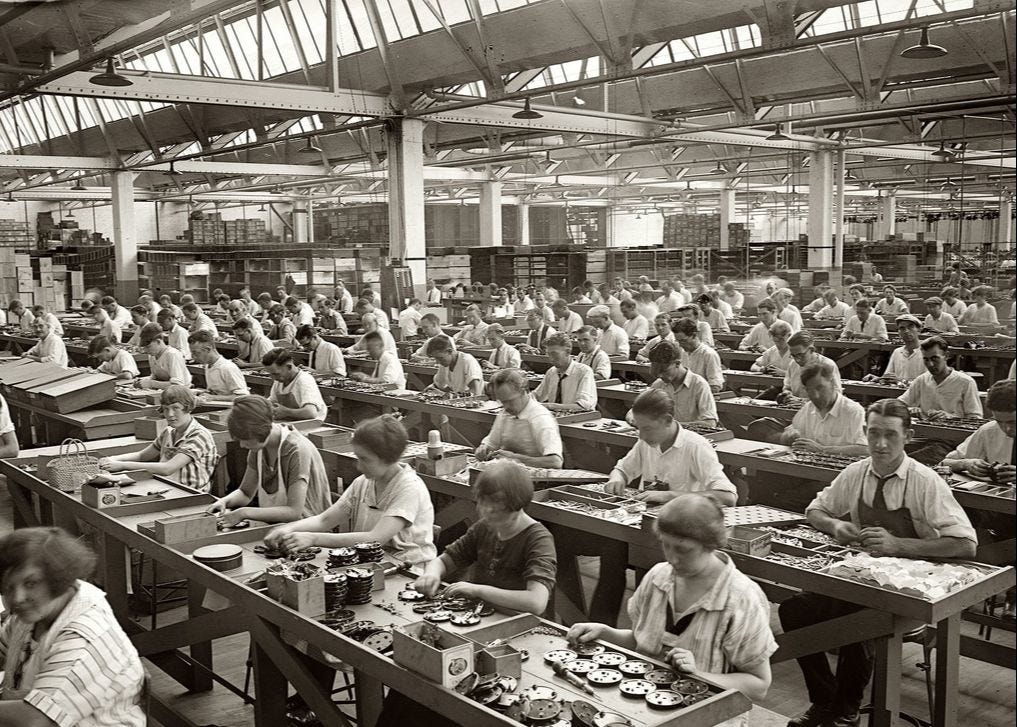

The great discovery of psychoanalysis was that of the production of desire, of the productions of the unconscious. (AO, 24)

Yet, with the terrifying presence of Oedipus, this discovery becomes lost within a series of symbols, all pertaining to parental figures:

But once Oedipus entered the picture, this discovery was soon buried beneath a new brand of idealism: a classical theater was substituted for the unconscious as a factory; representation was substituted for the units of production of the unconscious; and an unconscious that was capable of nothing but expressing itself — in myth, tragedy, dreams — was substituted for the productive unconscious. (AO, 24)

One of my favorite lines in the book is: “a classical theater was substituted for the unconscious as a factory.” In this passage, Deleuze and Guattari argue that Oedipus functions merely as a system of representations, reducing the unconscious to a theater with Oedipus is on stage.

- You want to read a blog post? Well, that’s just because you want to kill your father and have sexual relations with your mother.

- You want to write a blog post? Well, that’s just because you want to kill your father and have sexual relations with your mother.

Everything within Freudian psychoanalysis is reduced to Oedipus. Everything is constantly interpreted and examined. Instead, we ought to conceptualize the unconscious as a factory rather than substituting it with a classical theater with myth, tragedy, or dreams on stage.

Paragraph Six

So … why is explaining schizophrenia in relation to the ego problematic? Deleuze and Guattari state:

Every time that the problem of schizophrenia is explained in terms of the ego, all we can do is “sample” a supposed essence or a presumed specific nature of the schizo, regardless of whether we do so with love and pity or disgustedly spit out the mouthful we have tasted. (AO, 24)

Here, Deleuze and Guattari argue that when one attempts to understand schizophrenia through the lens of the ego, one mistakenly assumes an inherent nature or “supposed essence” of the schizo. Whether we are empathetic or disdainful towards the schizophrenic, the approach of understanding schizophrenia through the ego is inherently problematic. In this case, Deleuze and Guattari restate the ways in which the schizophrenic has been “sampled” by Kraepelin, Bleuler, and Binswanger:

We have “sampled” him once as a dissociated ego [Kraepelin’s dementia praecox], another time as an ego cut off from the world [Bleuler’s autism], and yet again — most temptingly — as an ego that had not ceased to be, who was there in the most specific way, but in his very own world, though he might reveal himself to a clever psychiatrist, a sympathetic superobserver — in short, a phenomenologist [Binswanger’s subjective experience].

(AO, 24; emphasis mine)

- It’s noteworthy that Deleuze and Guattari highlight Binswanger’s analysis of the schizophrenic as a phenomenologist, suggesting that the only aspect that should be understood is the schizophrenic’s direct spatiotemporal experience with the world.

Deleuze and Guattari continue by referring to Marx (this is another one of my favorite lines from the text):

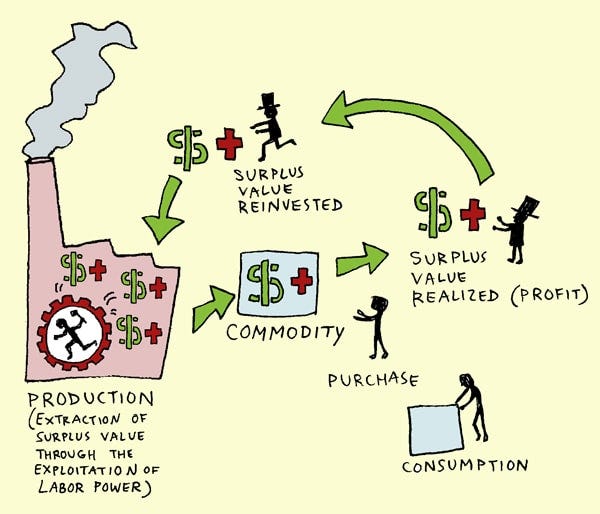

Let us remember once again one of Marx’s caveats: we cannot tell from the mere taste of wheat who grew it; the product gives us no hint as to the system and the relations of production. (AO, 24)

This reference to Marx originates from his seminal work Das Kapital, specifically, Part I, The Commodity. In this section, Marx writes:

From the taste of wheat it is not possible to tell who produced it, a Russian serf, a French peasant or an English capitalist.

(Das Kapital; emphasis mine)

Deleuze and Guattari argue that analyzing schizophrenia solely through the lens of the ego offers a limited perspective, hindering our ability to understand how both the schizophrenic and their associated symptoms are produced. Just as tasting wheat doesn’t reveal who grew it or the broader agricultural system behind it, focusing solely on the ego fails to uncover the deeper processes and social relations that contribute to the development of schizophrenia and its associated symptoms.

Thus, when a theoretician attempts to conceptualize schizophrenia through localized and abstract framework (such as those of Kraepelin, Blueler, and Binswanger), they fail to grasp the actual processes that produce the condition. Deleuze and Guattari write:

The product appears to be all the more specific, incredibly specific and readily describable, the more closely the theoretician relates it to ideal forms of causation, comprehension, or expression, rather than to the real process of production on which it depends. (AO, 24)

Yet, upon the examination and interrogation of the schizophrenic through localized and abstract methods, the schizophrenic appears as a clearly defined entity:

The schizophrenic appears all the more specific and recognizable as a distinct personality if the process is halted, or if it is made an end and a goal in itself, or if it is allowed to go on and on endlessly in a void, so as to provoke that “horror of . . . extremity wherein the soul and body ultimately perish” (the autist). Kraepelin’s celebrated terminal state. . .

(AO, 24)

Here, Deleuze and Guattari describe the schizophrenic as a clinical entity shaped by institutional practices. However, they do not confine their definition of the schizophrenic to just this clinical perspective. Instead, they argue that the schizophrenic is easily identified as a “distinct personality” through institutional, localized, and abstract methods employed to examine the schizophrenic. At any rate, common understandings of schizophrenia are rooted in clinical methods, which often involve the attempt to halt the process of production or turn the process of production into an end goal — such as policing the schizophrenic and forcing conformity. The schizophrenic one finds in mental institutions is a clinical entity; Deleuze and Guattari make a clear distinction between the schizophrenic as a clinical entity and the schizophrenic as a subject traversing the body without organs, aligning with nature as a process of production.

In the quote above, Deleuze and Guattari reference a passage from Aaron’s Rod by the prominent English novelist D.H. Lawrence to illustrate Kraepelin’s categorization of dementia praecox. Kraepelin’s approach (which views schizophrenia as a purely degenerative and worsening condition)— along with the attempts to halt the process of production or turn the process into an end goal — only continues to produce the symptoms that psychoanalysts aim to address.

However, what happens when we describe the schizophrenic through the material process of production? Deleuze and Guattari argue:

But the moment that one describes, on the contrary, the material process of production, the specificity of the product tends to evaporate, while at the same time the possibility of another outcome, another end result of the process appears. (AO, 24)

Earlier, we criticized abstract approaches to explaining schizophrenia as overly reductive, likening them to being unable to determine who grew wheat just by tasting it. Similarly, Deleuze and Guattari argue that defining schizophrenia through the material process of production —i.e., by examining the processes by which the condition developed, much like analyzing how wheat grew and who cultivated it — leads to a similar oversimplification. By concentrating on the material processes and who was involved, we risk homogenizing every grain of wheat from a field, reducing its essence to merely who grew it. In both cases — whether through an abstract method or a material process— we fall short in defining schizophrenia.

To put simply, Feurbach is the Clearambault of materialism.

Prior to the production of the schizophrenic as a clinical entity, it’s essential not to overlook what lies beneath it all (or rather, what schizophrenia is at the level of desiring-production). Deleuze and Guattari write:

Before being a mental state of the schizophrenic who has made himself into an artificial person through autism, schizophrenia is the process of the production of desire and desiring-machines.

(AO, 24; emphasis mine)

At this juncture, Deleuze and Guattari raise the question of how schizophrenia, as a process of production and desiring-machines, transitions to the schizophrenic as a clinical entity:

How does one get from one to the other, and is this transition inevitable? This remains the crucial question. (AO, 24)

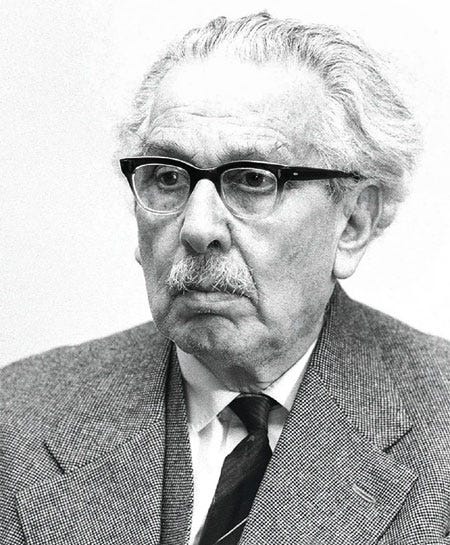

To answer this question, Deleuze and Guattari point to the insights of German-Swiss psychiatrist and philosopher Karl Jaspers:

Karl Jaspers has given us precious insights, on this point as on so many others, because his “idealism” was remarkably atypical. (AO, 24–25)

Now, let’s move on to describe Jasper’s atypical idealism.

Deleuze and Guattari examine how Jaspers diverges from conventional approaches to understanding and conceptualizing schizophrenia:

Contrasting the concept of process with those of reaction formation or development of the personality, he views process as a rupture or intrusion, having nothing to do with an imaginary relationship with the ego; rather, it is a relationship with the “demoniacal” in nature. (AO, 25)

Rather than framing schizophrenia in terms of and “reaction formation” or personality development, Jaspers finds schizophrenia to be like that of a rupture in the ongoing process of psychological development — a sudden disruption from normative processes.

Yet, Jaspers falls short:

The one thing Jaspers failed to do was to view process as material economic reality, as the process of production wherein Nature = Industry, Nature = History. (AO, 25)

By not relating schizophrenia to material economic realities, Jaspers unfortunately falls short in explaining schizophrenia. Deleuze and Guattari argue that a comprehensive understanding of schizophrenia requires connecting this rupture to broader sociohistorical processes.

Paragraph Seven

Deleuze and Guattari begin the seventh paragraph by discussing the logic of desire:

To a certain degree, the traditional logic of desire is all wrong from the very outset: from the very first step that the Platonic logic of desire forces us to take, making us choose between production and acquisition.

(AO, 25; emphasis mine)

From the earliest forms of Western philosophy, the understanding of desire has often been framed in terms of deficiency or lack. For the Ancient Greek philosopher, Plato, desire is viewed as yearning for what one is lacking (i.e., I desire something because I do not have it). A central aspect of Plato’s philosophy is his Theory of Forms. According to this theory, there exists a realm beyond the material world that is constituted by perfect, unchanging Forms or Ideas. These Forms represent the true essence of all things. In Plato’s view, the material world is merely a shadow of these ideal Forms which is best exemplified by Plato’s Allegory of the Cave (Book VII of Plato’s Republic).

For Plato, the philosopher’s goal is to seek knowledge of these Forms through contemplation. Thus, in a Platonist sense, desire is fundamentally understood as attaining what one lacks, specifically the perfect knowledge of the Forms that exists beyond the imperfect material world.

Deleuze and Guattari continue by describing the problem that arises when positioning desire in relation to acquisition:

From the moment that we place desire on the side of acquisition, we make desire an idealistic (dialectical, nihilistic) conception, which causes us to look upon it as primarily a lack: a lack of an object, a lack of the real object. (AO, 25)

When desire is framed in terms of acquisition, it is made into an idealistic, dialectical, and nihilistic concept. This perspective turns desire into an end goal, forever in search of attaining the perfect, lost object. In this manner, desire is understood in relation to lack — a deficiency or void that one seeks to fill by acquiring the lost object of desire.

- For the religious individual, one lacks God or holiness.

- For the capitalist, one lacks capital.

- For the psychoanalyst, one lacks the phallus.

Yet, we must not only conceptualize desire as acquisition; desire on the side of production hasn’t solely been absent:

It is true that the other side, the “production” side, has not been entirely ignored. (AO, 25)

Deleuze and Guattari characterize 18th-century German philosopher, Immanuel Kant, as offering a groundbreaking conceptualization of desire:

Kant, for instance, must be credited with effecting a critical revolution as regards the theory of desire, by attributing to it “the faculty of being, through its representations, the cause of the reality of the objects of these representations.” (AO, 25; emphasis mine)

Kant Citation — Start

In the quote above, Deleuze and Guattari reference the introduction to Kant’s book titled The Critique of Judgment, published in 1790, specifically citing a footnote:

But the following objection has been made to a similar explanation of the faculty of desire (Critique of Practical Reason, Preface, p. 16): that it cannot be defined as the faculty for being, through its representations, the cause of the reality of the objects of these representations, since mere wishes would also be desires, which, it is nevertheless admitted, cannot bring forth their objects. However, this proves nothing more than that there are also determinations of the faculty of desire in which it is in contradiction with itself: a phenomenon which is certainly noteworthy for empirical psychology (like noticing the influence that prejudices have on the understanding is for logic), but one which must not influence the definition of the faculty of desire considered objectively, that is, as it is in itself, before it is deflected from its determination by something else.

(Critique of the Power of Judgment, 32; emphasis mine)

As mentioned in the footnote above, Kant references his earlier work, Critique of Practical Reason, published in 1788. In this text (again, in another footnote), he writes:

The faculty of desire is a being’s faculty to be by means of its representations the cause of the reality of the objects of these representations.

(Critique of Practical Reason, 16; emphasis mine)

Kant Citation — End

Kant’s redefinition of desire is praised by Deleuze and Guattari (but is ultimately critiqued). The text from Kant is a bit confusing, so let’s clarify:

Kant’s view of desire departs from the traditional, Platonist notion of desire which conceptualizes desire in relation to acquiescence (also known as lack). For Platonism, something like hunger is understood in relation to lack: the subject lacks a sandwich (and attaining a sandwich would attempt to fulfill this lack). However, for Kant, desire is a productive force as “the faculty of being” — that is, human faculties (i.e., the subject’s mind) — represent objects and thus contribute to their existence. To use the previous example, Kant believes that when one is hungry, desire produces an image of a sandwich in the subject’s mind which causes the subject to go out and make a sandwich (or buy one).

Kant argues that desire is tied to the capacity for representation, meaning that objects of desire can exist conceptually in the mind even if they are not physically present. This approach emphasizes that desire involves an active process of representation(s), where the mind plays a crucial role in the existence and experience of desired objects.

— —

We will soon get to Deleuze and Guattari’s criticism of Kant’s view of desire, but as a side note, Kant’s argument has not been devoid of criticism writ large. Specifically, Kant has been criticized for including wishes within his definition of desire. If desire is defined as the capacity to cause or realize the reality of objects through representations, then wishes, which cannot always bring about their objects, would also fall under this definition. This inclusion leads to a contradiction because not all desires (e.g., wishes) result in the realization or actualization of their objects. This results in a contradiction (kantradiction?) within Kant’s definition of desire, as Kant doesn’t take into account the difference between desire and wishes.

Kant’s response to these criticisms is that, yes, there does exist an internal contradiction to the faculties of desire; however, Kant argues that we shouldn’t invalidate the concept of desire itself. Kant maintains that desire should be conceptualized as the capacity to represent and potentially realize objects, regardless of whether every instance of desire results in actual outcomes.

In any case, as we are reading Deleuze and Guattari’s works, we must focus on their criticism of Kant’s redefinition of desire. While they praise Kant’s departure from the traditional understanding of desire, they find that he doesn’t go far enough. Deleuze and Guattari write:

But it is not by chance that Kant chooses superstitious beliefs, hallucinations, and fantasies as illustrations of this definition of desire: as Kant would have it, we are well aware that the real object can be produced only by an external causality and external mechanisms; nonetheless this knowledge does not prevent us from believing in the intrinsic power of desire to create its own object — if only in an unreal, hallucinatory, or delirious form — or from representing this causality as stemming from within desire itself. (AO, 25)

Kant employs examples like hallucinations and superstitions to illustrate his definition of desire. Although Kant acknowledges that real objects are produced externally — with physical objects being produced from outside factors and not one’s mind (i.e., the sandwich is a real object that the subject makes or ends up buying)— Kant restricts desire to solely mental representations. Rather than conceptualizing desire as a process of production along with the sensations that produce subjectivity, Kant is limited in his view of desire as solely mental representations.

To summarize this point, we ought to refer to Chapter 1.3 where Deleuze and Guattari refer to hallucinations. They conclude that hallucinations and superstitions are the sole manifestation of desire fail to take into account a deeper I feel:

… The basic phenomenon of hallucination (I see, I hear) and the basic phenomenon of delirium (I think . . . ) presuppose an I feel at an even deeper level, which gives hallucinations their object and thought delirium its content. (AO, 18; emphasis mine)

Thus, in Kant’s view:

The reality of the object, insofar as it is produced by desire, is thus a psychic reality. (AO, 25; emphasis mine)

Kant’s belief that desire solely produces a “psychic reality” (indicating that desire is divorced from a material reality) is a narrow and limited view. Therefore, Kant’s redefinition of desire — while groundbreaking — changes nothing important:

Hence it can be said that Kant’s critical revolution changes nothing essential: this way of conceiving of productivity does not question the validity of the classical conception of desire as a lack; rather, it uses this conception as a support and a buttress, and merely examines its implications more carefully. (AO, 25)

In Kant’s framework, desire in relation to lack or acquisition persists. Kant’s focus on representations and “psychic realities” highlights the erroneous notion that mental constructs and “psychic realities” are separate from an actualized, material reality. Kant’s understanding of desire asserts that when a subject desires, wishes, or hallucinates an object, this very subject is lacking something and fundamentally divorced from these objects. (Kant fails to take into account desiring-production, partial objects as he is starting from the position of a global person.) Thus, while desire may produce mental images or representations of objects, these representations are a means to address what the subject is lacking or missing in the material world.

To put simply, Kant views desire as a mechanism aimed at addressing a lack. Instead, Deleuze and Guattari view desire as a productive force where they blur the lines between materiality and immateriality. There is no psychic reality, desire, wish, or series of hallucinations that exist independently from the subject being produced by feelings and sensations. The “I feel” precedes everything.

Paragraph Eight

Deleuze and Guattari continue:

In point of fact, if desire is the lack of the real object, its very nature as a real entity depends upon an “essence of lack” that produces the fantasized object. (AO, 25)

Here, Deleuze and Guattari argue that if desire is fundamentally linked to lack or acquisition, then the fantasized objects inherently possess an “essence of lack.” This perspective allows psychoanalysis to seamlessly explain desire producing fantasies:

Desire thus conceived of as production, though merely the production of fantasies, has been explained perfectly by psychoanalysis. (AO, 25)

Now … how do we interpret this? Deleuze and Guattari write:

On the very lowest level of interpretation, this means that the real object that desire lacks is related to an extrinsic natural or social production, whereas desire intrinsically produces an imaginary object that functions as a double of reality, as though there were a “dreamed-of object behind every real object,” or a mental production behind all real productions. (AO, 25–26)

Deleuze and Guattari argue that if we accept the idea that desire is in relation to lack, then the real object that is supposedly missing or absent relates to external social or environmental factors outside of the individual (i.e., one desires an object because they lack it). In response to this lack, desire internally generates a fantasy object that acts as a substitute for the real thing. This fantasy object serves as a “double of reality” — an imagined version that stands in for the real object. In this framework, every real object is obfuscated by an imaginary version of said object (“a mental production behind all real productions”).

Deleuze and Guattari go on to explain (while mocking psychoanalysis) that psychoanalysis isn’t inherently forced to psychoanalyze mundane objects, but it logically runs the risk of doing so:

This conception does not necessarily compel psychoanalysis to engage in a study of gadgets and markets, in the form of an utterly dreary and dull psychoanalysis of the object: psychoanalytic studies of packages of noodles, cars, or “thingumajigs.” (AO, 26)

Though psychoanalysis can engage in the study of noodles or cars, it tends not to. However, even with Kant’s reiteration of desire, there is this theatrical element to psychoanalysis:

But even when the fantasy is interpreted in depth, not simply as an object, but as a specific machine that brings desire itself front and center, this machine is merely theatrical, and the complementarity of what it sets apart still remains: it is now need that is defined in terms of a relative lack and determined by its own object, whereas desire is regarded as what produces the fantasy and produces itself by detaching itself from the object, though at the same time it intensifies the lack by making it absolute: an “incurable insufficiency of being,” an “inability-to-be that is life itself.”

(AO, 26; emphasis mine)

Deleuze and Guattari are not only critiquing psychoanalysis, but they are also critiquing Kant’s reiteration of desire and how this view of desire remains tied to the idea of lack (thus, tied to the psychoanalytic approach of desire). In Kant’s system, desire is still confined to a relationship with an object — with the object represented as a psychic reality (in one’s mind). Even when interpreting fantasy in depth, this view confines desire to representations. The object of desire is produced as a psychic reality and the subject lacks the real object. This conceptualization of fantasy serving as a machine or motor for representations is described as “theatrical,” where the unconscious becomes a stage with the (lost) object of desire playing a lead role.

To sum up this unfortunate progression:

Hence the presentation of desire as something supported by needs, while these needs, and their relationship to the object as something that is lacking or missing, continue to be the basis of the productivity of desire (theory of an underlying support). (AO, 26; emphasis mine)

To clarify the argument presented above, Deleuze and Guattari write:

In a word, when the theoretician reduces desiring-production to a production of fantasy, he is content to exploit to the fullest the idealist principle that defines desire as a lack, rather than a process of production, of “industrial” production. (AO, 26)

Whether in Kant, Freud, or Lacan, reducing desiring-production to the mere production of fantasy is arbitrary, severing desire from its productive process and placing it on a pedestal and declared unattainable. On this point, Deleuze and Guattari praise French philosopher and writer Clément Rosset for explaining this criticism well:

Clement Rosset puts it very well: every time the emphasis is put on a lack that desire supposedly suffers from as a way of defining its object, “the world acquires as its double some other sort of world, in accordance with the following line of argument: there is an object that desire feels the lack of; hence the world does not contain each and every object that exists; there is at least one object missing, the one that desire feels the lack of; hence there exists some other place that contains the key to desire (missing in this world).” (AO, 26)

In this quote, Deleuze and Guattari cite Rosset’s 1970 text Logique du pire (translated as Logic of the Worst). In Logique du pire, Rosset examines how people tend to imagine worst-case scenarios and project a negative version of reality onto the actual world, which leads to unnecessary suffering. This introduction of a negative counterpart (a negative world) parallels how Deleuze and Guattari critique psychoanalysis’ view of desire. As Rosset’s quote illustrates, psychoanalysis, by positioning desire in relation to lack, presupposes that the world is inherently incomplete or that there is always something missing. This leads to the imagination of an alternate realm where the missing object resides. As a result, desire is seen as insatiable within the material world, driving us to seek fulfillment of that lack through transcendental means.

Paragraph Nine

With all this discussion of desire, it’s important to ask: how do Deleuze and Guattari actually understand desire? They write:

If desire produces, its product is real. If desire is productive, it can be productive only in the real world and can produce only reality. Desire is the set of passive syntheses that engineer partial objects, flows, and bodies, and that function as units of production. The real is the end product, the result of the passive syntheses of desire as autoproduction of the unconscious. (AO, 26)

- Note: Deleuze and Guattari usethe term “passive” to describe the syntheses, which suggests that they are contesting the idea of an agent performing an action (since Deleuze and Guattari are dealing with partial objects instead of global persons). This terminology is also drawn from Difference and Repetition, where Deleuze examines the “active synthesis” in relation to conscious activity.

Unlike psychoanalysis positioning desire in relation to lack, Deleuze and Guattari view desire to be a productive force. Desire produces reality with the ‘real’ being the ultimate outcome of this production process.

They proceed to dismantle the notion of desire being defined in relation to lack:

Desire does not lack anything; it does not lack its object. It is, rather, the subject that is missing in desire, or desire that lacks a fixed subject; there is no fixed subject unless there is repression.

(AO, 26; emphasis mine)

In Chapter 1.3, we observed the presence of a subject traversing the surface of the body without organs. Here, Deleuze and Guattari emphasize that desire does not have a fixed subject (with this fixed subject being a Cartesian subject produced transcendentally). For them, beginning with the Cartesian subject implies starting with a global person. However, it is important to note that Deleuze and Guattari begin their discussion with partial objects and explain how the subject is continuously produced through the three syntheses, ultimately rising in the third synthesis.

At any rate, desire doesn’t lack anything. It doesn’t lack its object because … :

Desire and its object are one and the same thing: the machine, as a machine of a machine. Desire is a machine, and the object of desire is another machine connected to it. Hence the product is something removed or deducted from the process of producing: between the act of producing and the product, something becomes detached, thus giving the vagabond, nomad subject a residuum. (AO, 26; emphasis mine)

This passage critiques the concept of “lack.” In the Platonic and psychoanalytic traditions, desire is explained in relation to a perceived absence — one desires something precisely because it is something they do not have. However, in Deleuze and Guattari’s critique, desire is not understood in relation to lack because desire and its object are the same. Desiring-machines are connected to other desiring-machines within an interconnected network; lack, then, is not a natural, inherent quality but something erroneously produced (more of this will be discussed in Chapter 2). Regardless, in the framework of desiring-production, the relationship between production and product gives rise to a subject found in Chapter 1.3.

Deleuze and Guattari continue:

The objective being of desire is the Real in and of itself.* (AO, 26–27)

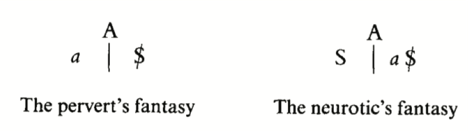

*Footnote: “Lacan’s admirable theory of desire appears to us to have two poles: one related to “the object small a” as a desiring-machine, which defines desire in terms of a real production, thus going beyond both any idea of need and any idea of fantasy; and the other related to the “great Other” as a signifier, which reintroduces a certain notion of lack. In Serge Leclaire’s article “La re’alite du desir” (Ch. 4, reference note 26), the oscillation between these two poles can be seen quite clearly.”

At this point, Deleuze and Guattari include a footnote explaining that the “object small a” (objet petit a) in psychoanalysis functions as a legitimate desiring-machine due to French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan linking the object small a to real production. However, they identify a problem with Lacan’s “great Other,” which acts as a signifier that renders these desiring-machines (or object small a) into unattainable objects of desire, situating desire into the framework of deficiency. In reality, desire has always been the production of the Real; for Deleuze and Guattari, it has always been the Real.

With all considering, Deleuze and Guattari reinforce their position by critiquing the notion of desire as solely being “psychic” — a term used by Kant, which has already been critiqued above:

There is no particular form of existence that can be labeled “psychic reality.” (AO, 27)

To make this point clearer, Deleuze and Guattari directly reference Marx:

As Marx notes, what exists in fact is not lack, but passion, as a “natural and sensuous object.” (AO, 27)

This quote appears to be a reference to to Marx’s Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 — specifically in the section titled ‘Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy in General’ — where Marx states:

To say that [hu]man is a corporeal, living, real, sensuous, objective being full of natural vigour is to say that [they have] real, sensuous objects as the object of [their] being or of [their] life, or that [they] can only express [their] life in real, sensuous objects. To be objective, natural and sensuous, and at the same time to have object, nature and sense outside oneself, or oneself to be object, nature and sense for a third party, is one and the same thing. (Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844)

In this way, Marx emphasizes the material and embodied aspects of human existence, where human life is defined not by lack, but by passion and real, tangible, sensuous objects. Regardless, many people understand desire in relation to need — particularly since the word “desire” is often used that way in everyday language — but it’s not need that bolsters desire; rather, it’s the opposite:

Desire is not bolstered by needs, but rather the contrary; needs are derived from desire: they are counterproducts within the real that desire produces. (AO, 27; emphasis mine)

In this way, needs serve as intensive quantities consumed in the third synthesis. In the same way that needs are derived from desire, so is lack:

Lack is a countereffect of desire; it is deposited, distributed, vacuolized within a real that is natural and social. (AO, 27; emphasis mine)

Lack being understood as a “countereffect of desire” implies that lack is produced by desire while manifesting within the real as an effect of desire. (The distinction between counterproducts and countereffects may be nomial, but this will be examined more in-depth in Chapter 10). When lack is understood as “deposited” and “distributed,” Deleuze and Guattari are explaining that lack, when produced, constitutes the Real and is “vacuolized” in the sense that lack serves as the creation of a gap or absence.

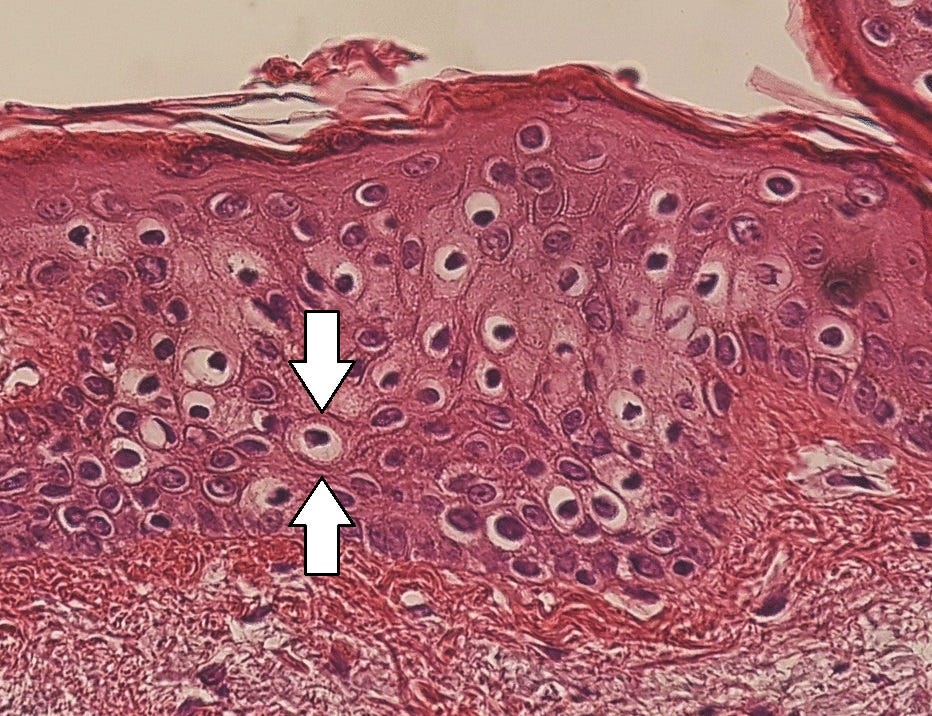

- “Vacuoles” is a biological term referring to storage structures within cells serving as a sort of empty space.

Deleuze and Guattari continue:

Desire always remains in close touch with the conditions of objective existence; it embraces them and follows them, shifts when they shift, and does not outlive them. For that reason it so often becomes the desire to die, whereas need is a measure of the withdrawal of a subject that has lost its desire at the same time that it loses the passive syntheses of these conditions. (AO, 27)

In this passage, Deleuze and Guattari discuss the dual nature of desire, which encompasses both life and death, challenging Freud’s notion of the “death instinct” (refer to Chapter 1.1). They argue that death is not merely an endpoint but a productive force in desiring-production. The “conditions of objective existence” that Deleuze and Guattari refer to are in a perpetual state of living and dying. As noted in Chapter 1.3, the subject undergoes constant rebirth through the consummation of intensive quantities, indicating that as it is reborn, it is also continually dying. Since desire is intertwined with its object, it does not separate from the object as it dies; instead, new conditions of objective experience emerge from this death. Ultimately, they conclude by asserting that needs serve as a counter-product of desire, as it “loses the passive syntheses of these conditions,” functioning as an active element in the unconscious.

They proceed:

This is precisely the significance of need as a search in a void: hunting about, trying to capture or become a parasite of passive syntheses in whatever vague world they may happen to exist in. (AO, 27)

This analysis further distinguishes need from desire, implicitly arguing that need should not be synonymous with desire. Need is linked to a “search in a void,” which captures the passive syntheses of the unconscious. When the subject says, “I need food,” it implies an awareness or consciousness of that need, but this understanding tends to reduce need as a mere starting and end point. However, need does not exist in isolation; need is constituted and produced by desire which creates connections and disconnections, emitting and interrupting flows that generate bodily sensations. Thus, the statement “I need food” emerges only after this complex interplay of desire. Further still:

It is no use saying: We are not green plants; we have long since been unable to synthesize chlorophyll, so it’s necessary to eat. . . . Desire then becomes this abject fear of lacking something. (AO, 27)

In this quote, Deleuze and Guattari critique the simplistic narratives that portray humans as uniquely burdened by desires that can never be fully satisfied, unlike plants that easily absorb sunlight. Deleuze and Guattari argue that this perspective fails by tying desire to a sense of lack or deficiency, leading us to believe that we are never consuming enough. Desire, for humans, is just as simple as desire in relation to a plant absorbing sunlight. Touch grass!

We must view desire as a productive force:

But it should be noted that [“we are not green plants”] is not a phrase uttered by the poor or the dispossessed. On the contrary, such people know that they are close to grass, almost akin to it, and that desire “needs” very few things — not those leftovers that chance to come their way, but the very things that are continually taken from them — and that what is missing is not things a subject feels the lack of somewhere deep down inside himself, but rather the objectivity of man, the objective being of man, for whom to desire is to produce, to produce within the realm of the real.

(AO, 27)

Deleuze and Guattari emphasize that this sense of lack, along with the associated fear, is not limited to individuals who are part of marginalized groups. In fact, those in lower societal positions are often “close to the grass,” meaning they are more attuned to desire. The desires of these marginalized individuals are not centered around excess of “leftovers” and meaningless goods, but rather revolve around the fundamental aspects of life that are constantly denied to them, such as dignity and basic resources. These subjects are not focused on an abstract, internal sense of lack, but on the material structures and societal conditions that shape their experiences.

Paragraph Ten

All of this culminates in desire producing the real; it’s always been the real:

The real is not impossible; on the contrary, within the real everything is possible, everything becomes possible. (AO, 27)

They continue:

Desire does not express a molar lack within the subject; rather, the molar organization deprives desire of its objective being. (AO, 27)

This is the first time where Deleuze and Guattari employ the term “molar,” emphasizing macro-level organization and rigid stability. Rather than diving into the specificities between the molar and molecular (which will be explained in depth later), we must note that desire does not represent a fundamental absence within the subject; desire does not express a molar organization of subjectivity as defined by the Cartesian subject. Rather, molar organization creates rigid subjects, and deprives desire of its “objective being,” making desire appear subjective in nature.

However, Deleuze and Guattari note that there are specific subjects that are keen on being objective:

Revolutionaries, artists, and seers are content to be objective, merely objective: they know that desire clasps life in its powerfully productive embrace, and reproduces it in a way that is all the more intense because it has few needs. And never mind those who believe that this is very easy to say, or that it is the sort of idea to be found in books.

(AO, 27; emphasis mine)

The specific subjects listed — revolutionaries, artists, and seers — are content with decentering the self in an objective way, embracing the powerful (albeit loosely defined) nature of desiring-production. At the end of this quote, Deleuze and Guattari playfully poke fun at themselves by saying that the objective nature of these subjects cannot be found in books — yet we are encountering this idea within a book, adding a facetious touch. It appears that they are suggesting that books, probably specific to the philosophical kind, reduce or over-theorize ideas, turning them into something abstract rather than something lived or experienced.

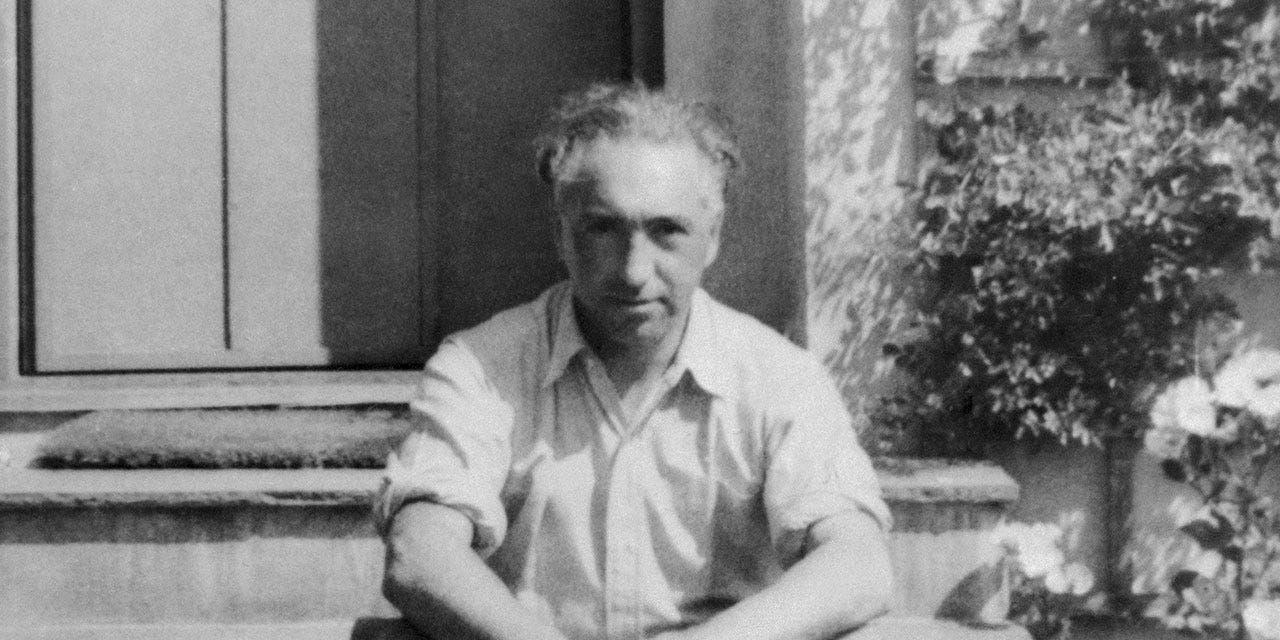

Ironically enough, after making fun of the notion that these objective contents can be found in books, Deleuze and Guattari go on to reference the American novelist Henry Miller and his 1949 book Sexus:

“From the little reading I had done I had observed that the men who were most in life, who were moulding life, who were life itself, ate little, slept little, owned little or nothing. They had no illusions about duty, or the perpetuation of their kith and kin, or the preservation of the State. . . . The phantasmal world is the world which has never been fully conquered over. It is the world of the past, never of the future. To move forward clinging to the past is like dragging a ball and chain.”

(AO, 27–28; emphasis mine)

Sexus is the opening book of The Rosy Crucifixion trilogy, a semi-autobiographical series that chronicles six years of Miller’s life. Adding yet another layer of irony, Miller’s quoted passage reflects on his experience reading books and observing that those who didn’t focus on accumulating wealth were the ones truly “most in life.”

Deleuze and Guattari go on to describe what those who are “most in life” appear to be like:

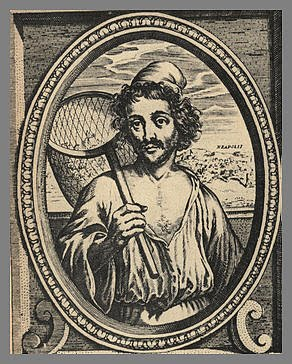

The true visionary is a Spinoza in the garb of a Neapolitan revolutionary. (AO, 28)

By invoking 17th Century Baruch Spinoza, one of Deleuze and Guattari’s most idolized philosophers, as a “Neapolitan revolutionary”, they are painting the image of an individual who couples deep, philosophical thought with radical action. This also references a moment in Deleuze’s Spinoza: Practical Philosophy published in 1970 where he writes about how Spinoza used to draw himself “in the attitude and costume of the Neapolitan revolutionary Masaniello.”

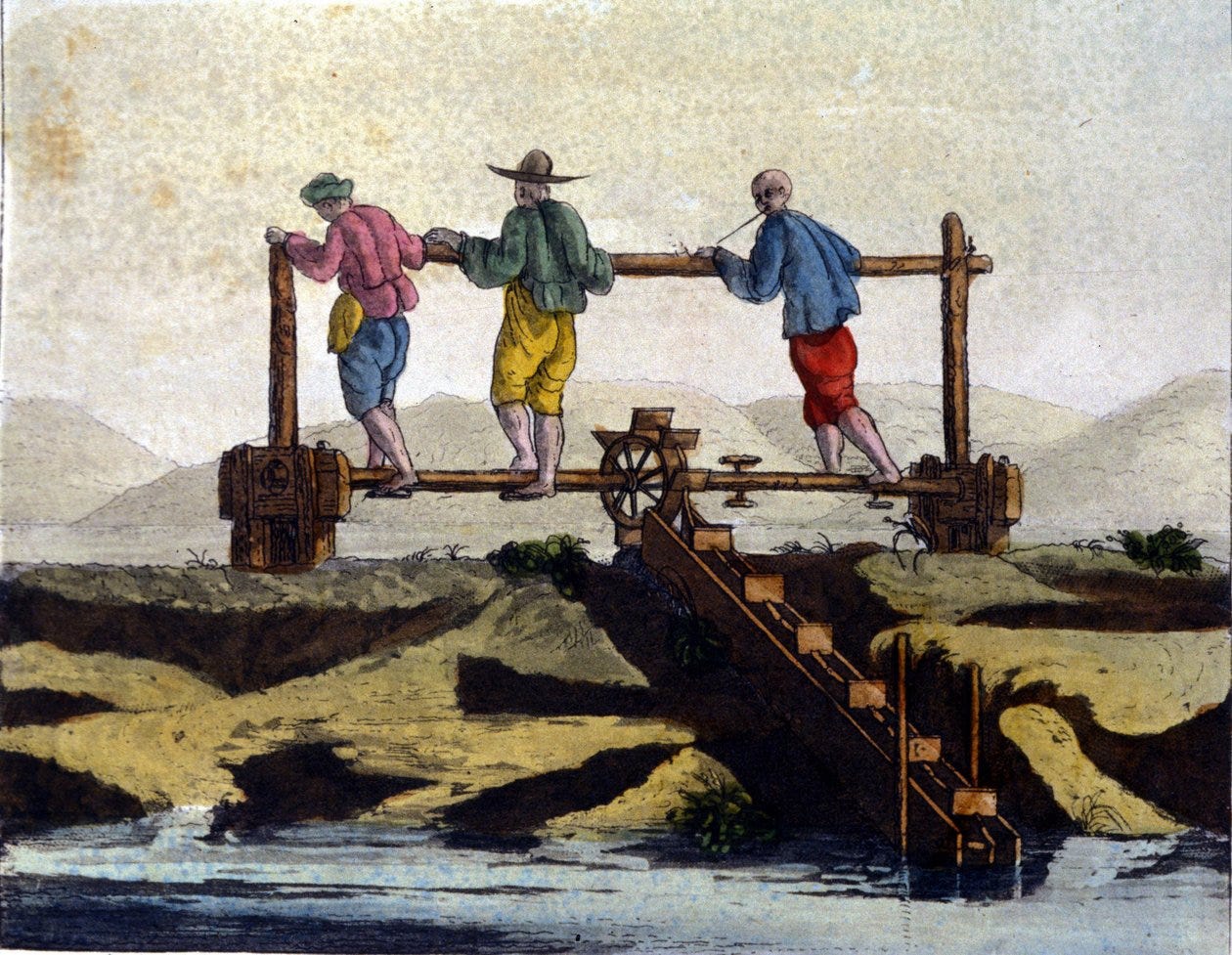

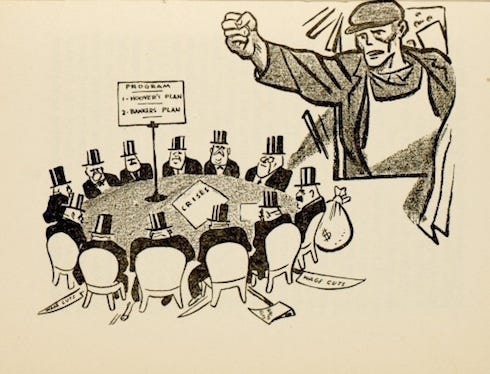

Here is the drawing for context:

They continue:

We know very well where lack — and its subjective correlative — come from. (AO, 28)

- This “subjective correlative” refers to “molar organization depriving desire of its objective being” and transformed into something deemed subjective.

Lack (manque)* is created, planned, and organized in and through social production. (AO, 28)

Let’s start with the translators’ note:

*The French word manque may mean both lack and need in a psychological sense, as well as want or privation or scarcity in an economic sense. Depending upon the context, it will hence be translated in various ways below. (Translators’ note.)

In the translators’ note, they isolate that the French word “manque” has the ability to mean “lack and need in a psychological sense.” As stated earlier, lack is understood as a countereffect of desire, while need is understood as a counterproduct of desire. However, when “need” is conceptualized in this psychological sense, that is to say, thought of as preceding desire, it is akin to lack.

This is why, in the sentence directly after, Deleuze and Guattari write:

(Manque) is counterproduced as a result of the pressure of antiproduction; the latter falls back on (se rabat sur) the forces of production and appropriates them. (AO, 28; emphasis mine)

Notice how the word “manque” is used in the sense of being “counterproduced.” And also notice that they purposefully used the word “manque” instead of “besoin” (which is the French word for “need”) This seems to indicate that lack and need are functionally the same when understood as a counterproduction that is a “result of the pressure of antiproduction.”

Now that we’ve cleared up some confusion, let’s review those quotes with more precision:

Lack (manque) is created, planned, and organized in and through social production. (AO, 28)

At this juncture, Deleuze and Guattari present social production as a key factor in the creation of lack. In Chapter 1.2, we observed the connection between desiring-production and social production; however, Deleuze and Guattari do not thoroughly explore why “lack is created through social production” here. In the eleventh paragraph, we will discover that social production is, in essence, desiring-production “under determinate conditions”, meaning that these conditions influence the creation of lack.

Furthermore:

(Manque) is counterproduced as a result of the pressure of antiproduction; the latter falls back on (se rabat sur) the forces of production and appropriates them. (AO, 28; emphasis mine)

Lack is counterproduced by desire through social production, and due to the body without organ’s antiproductive nature, the body without organs falls back upon (se rabat sur) the process of production. Consequently, lack is continuously appropriated, making it seem as though lack emanates from the surface of recording. Because of this. Deleuze and Guattari reiterate their earlier thesis that need and lack are not pre-existing or primary:

[Manque] is never primary; production is never organized on the basis of a pre-existing need or lack (manque).

(AO, 28)

It is lack that infiltrates itself, creates empty spaces or vacuoles, and propagates itself in accordance with the organization of an already existing organization of production.*

(AO, 28; emphasis mine)

In a footnote here, Deleuze and Guattari cite French writer Maurice Clavel’s critique of French existentialist Jean-Paul Sartre, emphasizing Clavel’s observation that Marx was wise to not define scarcity as a starting premise of capitalism. Had Marx done so, it would imply that supply and demand operate as fundamental, unchangeable forces, rather than a result of specific sociohistorical conditions. This approach suggests that Marx viewed scarcity not as a natural, inherent drive toward fulfilling a lack but as something constructed within the capitalist system. In parallel, Deleuze and Guattari argue that lack is not a natural state but is created by a pre-existing system of production, which organizes desire and need according to the demands of the capitalist structure.

At any rate, to analyze the quote above more directly, lack embeds itself by continually generating empty spaces with, establishing the very sense of lack that it produces. Deleuze and Guattari make clear that lack doesn’t emerge from somewhere outside of the production process — it aligns itself with the organization of “an already existing organization of production.” To explain this point more clearly, Deleuze and Guattari parallel the creation of lack to a market economy, like that of capitalism. They write:

The deliberate creation of lack as a function of market economy is the art of a dominant class. This involves deliberately organizing wants and needs (manque) amid an abundance of production; making all of desire teeter and fall victim to the great fear of not having one’s needs satisfied; and making the object dependent upon a real production that is supposedly exterior to desire (the demands of rationality), while at the same time the production of desire is categorized as fantasy and nothing but fantasy. (AO, 28; emphasis mine)

- Deleuze and Guattari make a strategic move here by highlighting how desire is relegated to the realm of fantasy under capitalism — a term Lacan uses to describe a bridge between desire and reality. Yet, they note that desire was never fantasy — it’s always been real.

- The phrase “demands of rationality” refers to how the transcendent concept of rationality is produced alongside this process, upholding this production of lack.

In the market economy, lack is deliberately constructed amidst abundant production, created a system where everyone could, theoretically, have their basic needs met but are, instead, made to feel constant insecurity. Within a system of capitalism, desire is always understood as something unfulfilled, fueling an endless cycle of wanting. This process disconnects the object of desire from desire itself, reducing desire’s productive capacity to mere “fantasy” rather than recognizing desire as a real, productive force.

Paragraph Eleven

Deleuze and Guattari begin this paragraph by problematizing the false dichotomy between social production and desiring-production:

There is no such thing as the social production of reality on the one hand, and a desiring-production that is mere fantasy on the other. (AO, 28)

It is not enough to say that social production produces reality and desiring-production produces fantasy. The notion that we can draw a simple, straightforward connection between social production and desiring-production lies in a reductive framework as they are both interconnected, simultaneously shaping one another. Deleuze and Guattari write:

The only connections that could be established between these two productions would be secondary ones of introjection and projection, as though all social practices had their precise counterpart in introjected or internal mental practices, or as though mental practices were projected upon social systems, without either of the two sets of practices ever having any real or concrete effect upon the other. (AO, 28; emphasis mine)

Deleuze and Guattari dismiss the idea of secondary connections between social production and desiring-production, arguing that such connections are solely based on introjection and projection. This means that efforts to align social production with internal psychological processes (introjection) or to correspond internal psychological processes with social production (projection) are overly simplistic. This simplification is problematic because it neglects to demonstrate how these two forms of production actively effect one another.

For the sake of enjoyment, let’s imagine a perfect parallel between the two forms of production:

As long as we are content to establish a perfect parallel between money, gold, capital, and the capitalist triangle on the one hand, and the libido, the anus, the phallus, and the family triangle on the other, we are engaging in an enjoyable pastime, but the mechanisms of money remain totally unaffected by the anal projections of those who manipulate money. (AO, 28)

Deleuze and Guattari suggest that while we can imagine a parallel between capitalism as a form of social production (capitalist triangle) and the oedipalized unconscious (family triangle), this does not change the fundamental reality that money is exchanged regardless of the psychological projections of those who handle it. Thus:

The Marx-Freud parallelism between the two remains utterly sterile and insignificant as long as it is expressed in terms that make them introjections or projections of each other without ceasing to be utterly alien to each other, as in the famous equation money = shit. (AO, 28–29)

- When Deleuze and Guattari assert that “money = shit,” they are making a provocative statement that highlights Marx’s focus on the exchange of money and Freud’s emphasis on feces in the anal stage, which symbolizes a child’s relationship with their parents, often characterized as “anal-retentive” or “anal-expulsive.”

The false dichotomy between social production and desiring-production that arises from Marx’s exclusive focus on the political economy and Freud’s exclusive focus on the libidinal economy is flawed. This narrow framing relies on introjection or projection, obscuring the intricate relationship between the two. As we will soon learn: the political economy and libidinal economy are one and the same thing; or rather, two sides of the same coin.

Deleuze and Guattari conclude this paragraph by describing the true relationship between social production and desiring-production:

The truth of the matter is that social production is purely and simply desiring-production itself under determinate conditions. We maintain that the social field is immediately invested by desire, that it is the historically determined product of desire, and that libido has no need of any mediation or sublimation, any psychic operation, any transformation, in order to invade and invest the productive forces and the relations of production. There is only desire and the social, and nothing else. (AO, 29)

To reiterate: social production is desiring-production under determinate conditions. From my understanding, these “determinate conditions” manifest as social structures and historical conditions; they are the frameworks by which we conceptualize society. However, as it must be stated clearly: the social field and desire and intrinsically connected — there is “no need of any mediation” between the two.

Paragraph Twelve

Though desire is presented as a sort of liberatory force throughout Chapters 1.1–1.3, we must not assume that desire isn’t responsible for problematic forms of social production:

Even the most repressive and the most deadly forms of social reproduction are produced by desire within the organization that is the consequence of such production under various conditions that we must analyze. (AO, 29)

That said, Deleuze and Guattari pose two fundamental questions that form the basis of the issues addressed in Anti-Oedipus. (This might be my favorite part of the work):

That is why the fundamental problem of political philosophy is still precisely the one that Spinoza saw so clearly, and that Wilhelm Reich rediscovered: “Why do men fight for their servitude as stubbornly as though it were their salvation?” How can people possibly reach the point of shouting: “More taxes! Less bread!”?

(AO, 29; emphasis mine)

- The quote “More taxes! Less bread!” comes from the first chapter of Lewis Carroll’s 1889 novel Sylvie and Bruno, which is titled Less Bread! More Taxes!

It may seem surprising that individuals vote for leaders who are directly opposed to their interests (whether it be opposing healthcare, tax cuts for the rich, etc.), yet most do not question this behavior. Consequently, the questions raised by Deleuze and Guattari (or, more accurately, by Spinoza and Austrian psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich) are largely intuitive.

Deleuze and Guattari proceed by building on Reich’s work:

As Reich remarks, the astonishing thing is not that some people steal or that others occasionally go out on strike, but rather that all those who are starving do not steal as a regular practice, and all those who are exploited are not continually out on strike: after centuries of exploitation, why do people still tolerate being humiliated and enslaved, to such a point, indeed, that they actually want humiliation and slavery not only for others but for themselves?

(AO, 29; emphasis mine)

Reich is correct to point out that we shouldn’t be surprised as to why some individuals resort to theft — after all, some people will inevitably steal in an inequitable economic system. What is truly surprising is that theft isn’t a common practice among those who are starving. Another example he offers is that individuals don’t frequently go on strike when they are exploited at work. However, it’s important to recognize that Deleuze and Guattari are not merely claiming that people simply endure or tolerate these conditions; rather, they assert that people actually desire these conditions for themselves and others.

As Deleuze and Guattari assert:

Reich is at his profoundest as a thinker when he refuses to accept ignorance or illusion on the part of the masses as an explanation of fascism, and demands an explanation that will take their desires into account, an explanation formulated in terms of desire: no, the masses were not innocent dupes; at a certain point, under a certain set of conditions, they wanted fascism, and it is this perversion of the desire of the masses that needs to be accounted for. (AO, 29)

In this vein, Reich is correct in maintaining that “the masses were not innocent dupes” and we cannot blame ignorance as the cause of their acceptance of fascism. They wanted fascism.

Paragraph Thirteen

Before they praise Reich too much, Deleuze and Guattari note Reich’s error:

Yet Reich himself never manages to provide a satisfactory explanation of this phenomenon, because at a certain point he reintroduces precisely the line of argument that he was in the process of demolishing, by creating a distinction between rationality as it is or ought to be in the process of social production, and the irrational element in desire, and by regarding only this latter as a suitable subject for psychoanalytic investigation.

(AO, 29)