Examining a pivotal seminar where Lacan interprets Edgar Allan Poe’s short story

Lacan begins his seminar on The Purloined Letter by positioning the listener —or, in this case, the reader — in the midst of a reflective process:

Our inquiry has led us to the point of recognizing that the repetition automatism finds its basis in what we have called the insistence of the signifying chain.

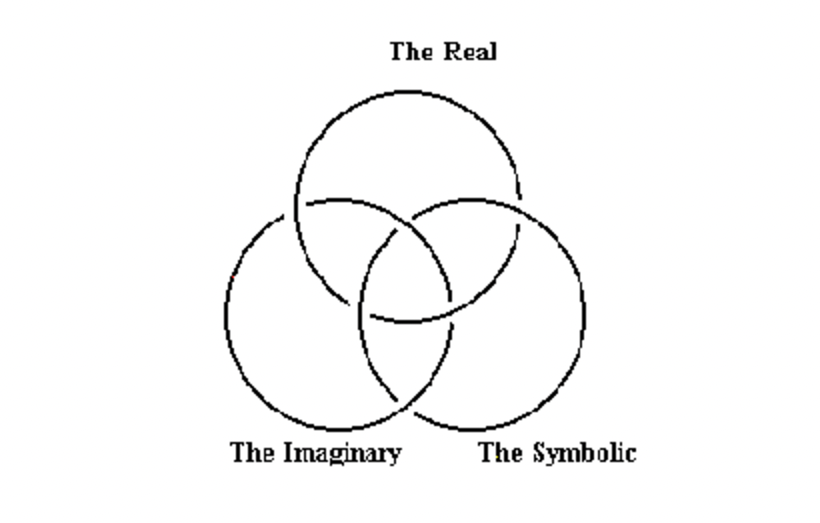

This first sentence starts strong by invoking “repetition automatism,” a concept rooted in Sigmund Freud’s framework, particularly in his 1920 essay Beyond the Pleasure Principle. In this work, Freud defines repetition automatism as the compulsive, unconscious repetition of certain behaviors, even when they lead to suffering. This could look like individuals repeatedly checking to see if the door is locked, people who unconsciously choose distant partners as a result of childhood abandonment, or ruminating on negative thoughts. Lacan expands on this idea by situating repetition automatism within the symbolic order — one of the three registers that serves as the domain of language, rules, conventions, and social norms. Specifically, Lacan’s reference to the “signifying chain” describes how the symbolic order operates: various signs and signifiers link to one another, similar to how letters and words form sentences and syntax in language, making the unconscious structured like a language. Lacan continues:

We have elaborated that [repetition automatism finding its basis in the signifying chain] itself as a correlate of the ex-sistence (or: eccentric place) in which we must necessarily locate the subject of the unconscious if we are to take Freud’s discovery seriously.

In this context, repetition automatism is not arbitrary or random but is rooted and structured within the symbolic order. Lacan emphasizes that this connection demonstrates how repetition automatism has a correlate, which he terms ‘ex-sistence’ (or ‘eccentric place’). These terms refer to the subject of the unconscious, whose position lies outside a self-contained ego. This subject is shaped by the signifying chain but is not conscious of it; the subject is defined as ‘ex-sistence’ because it is positioned within the symbolic order yet remains unaware of it. The subject’s experience is mediated by this signifying chain, though the subject remains oblivious to its influence.

Lacan continues to elaborate on the importance of the symbolic order:

As is known, it is in the realm of experience inaugurated by psychoanalysis that we may grasp along what imaginary lines the human organism, in the most intimate recesses of its being, manifests its capture in a symbolic dimension.

Here, Lacan argues that psychoanalysis provides the tools to understand how the subject is caught in the symbolic order, influencing even the most intimate aspects of their being. This includes not only language and societal structures but also the realm of images and self-identifications, where the symbolic order still plays a crucial role.

So … what is the lesson of this seminar? Lacan states:

The lesson of this seminar is intended to maintain that these imaginary incidences, far from representing the essence of our experience, reveal only what in it remains inconsistent unless they are related to the symbolic chain which binds and orients them.

In the imaginary register, a subject’s ego and sense of self are formed through identifications with images. However, these identifications are based on an incomplete and fragmented view of the self, originating from the mirror stage where the child first identifies with an external image of themselves. This initial identification is not unified; the subject sees themselves in the mirror, but this image remains a false unity or idealized projection: it isn’t the subject, but an image of the subject. Therefore, because imaginary identifications are based on a fragmented view of the self and others, they remain inherently inconsistent and belong to the realm of illusion or fantasy. Thus, only by linking these imaginary incidences to the symbolic chain can one fully understand the depth of subjectivity

This is not to suggest any kind of hierarchy among the registers:

We realize, of course, the importance of these imaginary impregnations in those partializations of the symbolic alternative which give the symbolic chain its appearance.

Lacan observes that the imaginary is not a separate or isolated register from the symbolic; rather, it actively shapes and influences the symbolic order. The imaginary “impregnates” or affects the symbolic, as the symbolic becomes fragmented or “partialized” by the subject’s experiences in the imaginary, with their images of identification influencing how signs are interpreted in the symbolic. For example, imagine a person who, as a child associated the image of fatherhood with their father. In the imaginary register, this individual forms an image or identification of what fatherhood should look like. However, as they grow older, they are exposed to other social norms and conventions regarding parenting and fatherhood. Despite these new influences, the original identification with their father as an image of fatherhood “impregnates” or imposes itself on the symbolic order, causing the signifying chain to appear in a particular way which results in a fragmented or partialized understanding of the symbolic. Lacan continues:

But we maintain that it is the specific law of that chain which governs those psychoanalytic effects that are decisive for the subject: such as foreclosure, repression, denial itself-specifying with appropriate emphasis that these effects follow so faithfully the displacement of the signifier that imaginary factors, despite their inertia, figure only as shadows and reflections in the process.

Regardless of the influence the imaginary has on the symbolic, there is a law or code that governs the symbolic chain. Lacan highlights several processes — such as foreclosure, repression, and denial — which follow this law of the chain. Let’s break them down:

- Foreclosure: This refers to the exclusion or rejection of a key signifier from the symbolic order, which disrupts the subject’s ability to integrate this signifier into their conceptualization of reality. (The result of foreclosure can be psychosis, as the excluded signifer cannot be processed in the subject’s experience).

- Repression: This refers to the process of pushing certain desires or thoughts out of consciousness (or preventing them from reaching consciousness). (The result of repression can be neurosis as the repressed material never disappears but shows up in dreams, slips of the tongue, etc.).

- Denial: This refers to a subject refusing to acknowledge a specific sign that is present in the symbolic order. This occurs when there is a conflict between the sign and ego or self-image. (This can result in both psychosis and neurosis i.e., through a refusal of acknowledging an addiction).

Lacan continues:

But this emphasis would be lavished in vain, if it served, in your opinion, only to abstract a general type from phenomena whose particularity in our work would remain the essential thing for you, and whose original arrangement could be broken up only artificially.

At this point, Lacan emphasizes the importance of conducting a detailed and nuanced analysis, rather than one that is too general or broad. Because of this emphasis on specificity, Lacan points out that one can better understand certain concepts by focusing on a particular form of analysis, which, in this case, will be presented through a story. This story serves as a way to demonstrate how the subject is shaped by the symbolic order and the signifying chains that compose it:

Which is why we have decided to illustrate for you today the truth which may be drawn from that moment in Freud’s thought under study-namely, that it is the symbolic order which is constitutive for the subject-by demonstrating in a story the decisive orientation which the subject receives from the itinerary of a signifier.

In the story that will be explored shortly, a specific signifier plays a key role in shaping the subject’s development. As Lacan explains:

It is that truth, let us note, which makes the very existence of fiction possible.

To be clear, without this symbolic framework (i.e., signifying chains that shape our subjectivity) fiction would not exist because fiction relies on the ability to create meaning which can only occur within the symbolic order. Furthermore, the ability to manipulate these signifiers in order to craft stories serves of special importance in both the creation and interpretation of narratives. To continue:

And in that case, a fable is as appropriate as any other narrative for bringing it to light — at the risk of having the fable’s coherence put to the test in the process.

On one hand, a fable — like any other story — has the capacity to be an effective tool for illustrating the truth of something. On the other hand, the very nature of fables may be tested in the process, revealing inherent flaws and making them an inconsistent object of study. Without getting too lost in the details, Lacan emphasizes the importance of examining fiction:

Aside from that reservation, a fictive tale even has the advantage of manifesting symbolic necessity more purely to the extent that we may believe its conception arbitrary.

Examining made-up stories allows us to explore meaning without being constrained by the confines of reality.

Lacan explains the purpose of the specific story he has selected for analysis:

Which is why, without seeking any further, we have chosen our example from the very story in which the dialectic of the game of even or odd — from whose study we have but recently profited — occurs.

In the story Lacan chooses, he highlights the dialectic of the game of “even or odd.” What he means by this is that the game — which will be explained in detail later — involves conflict and interaction, where each move builds upon the previous one, progressing in a linear fashion. (Sometimes, the game is also known as “odds and evens”). Lacan then discusses that this story was not chosen by accident:

It is, no doubt, no accident that this tale revealed itself propitious to pursuing a course of inquiry which had already found support in it.

Thus, it is clear that this story is both useful and necessary for our analysis of the signifying chain in relation to repetition automatism. Now, per the title of this seminar, it is obvious that Lacan is referring to the short story — The Purloined Letter — written by American author Edgar Allen Poe in 1844.

As you know, we are talking about the tale which Baudelaire translated under the title “La lettre volée.”

- Lacan points out that he is referring to the version of The Purloined Letter translated by the French poet Charles Baudelaire.

Lacan further elaborates:

At first reading, we may distinguish a drama, its narration, and the conditions of that narration. We see quickly enough, moreover, that these components are necessary and that they could not have escaped the intentions of whoever composed them.

For Lacan, it is easy to identify three distinct elements in this story: the narration, which involves the characters and plot in a dramatic sequence, along with a specific set of circumstances in which the narrator is involved. Lacan uses the term “whoever” to detach the author, Poe, from the creative process, emphasizing that the necessary components of the story were carefully constructed, regardless of the author’s identity. All of these elements were essential to the formation of The Purloined Letter.

Lacan continues to comment on the narration itself:

The narration, in fact, doubles the drama with a commentary without which no mise en scene would be possible.

In this story, narration serves not only to tell the events but also to enhance the dramatization of the plot. Without it, no mise-en-scène — a French term meaning “setting the stage” — would be possible. Perhaps, conceptualizing the entire story would be impossible without proper narration:

Let us say that the action would remain, properly speaking, invisible from the pit — aside from the fact that the dialogue would be expressly and by dramatic necessity devoid of whatever meaning it might have for an audience: in other words, nothing of the drama could be grasped, neither seen nor heard, without, dare we say, the twilighting which the narration, in each scene, casts on the point of view that one of the actors had while performing it.

Lacan draws an analogy to the theater, referencing the “pit,” the area where the audience sits (or where the orchestra is located just below the stage, allowing the audience to watch the performance). Without proper narration, the audience would not be able to fully see or hear the stage action. Additionally, without narration, the dialogue would be “devoid of meaning,” as nothing could be comprehended. In this way, narration provides the meaning necessary to grasp the performance.

One important point to note, however, is that Lacan is not suggesting the story exists as a single scene. Rather, he will use this story to illustrate clear examples of a primal scene and its secondary repetition:

There are two scenes, the first of which we shall straightway designate the primal scene, and by no means inadvertently, since the second may be considered its repetition in the very sense we are considering today.

This will be the crux of Lacan’s analysis that will be examined further on.

Now … what is the primal scene that Lacan is talking about? He writes:

The primal scene is thus performed, we are told, in the royal boudoir, so that we suspect that the person of the highest rank, called the “exalted personage,” who is alone there when she receives a letter, is the Queen.

When Lacan refers to the concept of the “primal scene,” he is not using it in the traditional Freudian sense of the child’s first awareness of their parents’ sexual activity. Instead, Lacan is referring to a key moment in the story of The Purloined Letter — the realization of the letter containing sensitive information. This event takes place in the royal boudoir, a private room, where the Queen receives the letter. The suggestion of this being the primal scene is further supported when one considers the contents of the letter:

[The setting of the primal scene] is confirmed by the embarrassment into which she is plunged by the entry of the other exalted personage, of whom we have already been told prior to this account that the knowledge he might have of the letter in question would jeopardize for the lady nothing less than her honor and safety.

The Queen’s reaction, as other high-ranking officials enter the room, confirms the reader’s suspicions: the letter contains sensitive information that she fears could lead to embarrassment and danger if exposed. To provide more context, earlier in the story, the reader is informed that anyone who enters the room while the Queen is receiving the letter could potentially jeopardize her if they possess the letter in question. One might suspect the King could jeopardize the Queen but this is soon proven erroneous:

Any doubt that he is in fact the King is promptly dissipated in the course of the scene which begins with the entry of the Minister D-.

At this point, the reader is already aware that Minister D-, by possessing the letter, poses a threat to the Queen. Nevertheless, the Queen makes no effort to draw attention to the letter:

At that moment, in fact, the Queen can do no better than to play on the King’s inattentiveness by leaving the letter on the table “face down, address uppermost.”

Despite the Queen’s efforts to conceal the letter, Minister D- notices it:

It does not, however, escape the Minister’s lynx eye, nor does he fail to notice the Queen’s distress and thus to fathom her secret.

Lacan emphasizes that the Minister’s eyesight is comparable to that of a lynx, an animal renowned for its sharp vision, symbolizing exceptional perceptiveness or insight.

Now that the stage is set, Lacan writes:

From then on everything transpires like clockwork.

Lacan then goes on to explain how Minister D- manages to steal the letter:

After dealing in his customary manner with the business of the day, the Minister draws from his pocket a letter similar in appearance to the one in his view, and, having pretended to read it, he places it next to the other.

This was executed cunningly yet the Queen noticed that the Minister took the letter:

A bit more conversation to amuse the royal company, whereupon, without flinching once, he seizes the embarrassing letter, making off with it, as the Queen, on whom none of his maneuver has been lost, remains unable to intervene for fear of attracting the attention of her royal spouse, close at her side at that very moment.

Since the Queen was focused on keeping the King from noticing the letter, she could not risk drawing attention to it without exposing herself. This, in turn, underscores the Minister’s power over the Queen:

Everything might then have transpired unseen by a hypothetical spectator of an operation in which nobody falters, and whose quotient is that the Minister has filched from the Queen her letter and that-an even more important result than the first — the Queen knows that he now has it, and by no means innocently.

Finally, in regards to the first scene, Lacan explains:

A remainder that no analyst will neglect, trained as he is to retain whatever is significant, without always knowing what to do with it: the letter, abandoned by the Minister, and which the Queen’s hand is now free to roll into a ball.

The “remainder” that Lacan refers to is what is left behind — in this case, the letter discarded by the Minister. Regardless of how the psychoanalyst chooses to interpret this remainder, its very existence is significant. The remainder symbolizes something unresolved or left over in the situation (might it be unresolved repression?). With the Minister’s letter now in the Queen’s possession, the Queen is free to crumple it, as an expression of her anger.

This marks the end of the first scene — the primal scene — for Lacan.

Lacan turns to the second scene:

Second scene: in the Minister’s office.

The stolen letter is known to be in the Minister’s possession, specifically within his office, but the precise location remains a critical question. The task of retrieving this letter falls to the Prefect of Police, Monsieur G-, who is determined to recover it:

It is in [the Minister’s] hotel, and we know-from the account the Prefect of Police has given Dupin, whose specific genius for solving enigmas Poe introduces here for the second time — that the police, returning there as soon as the Minister’s habitual, nightly absences allow them to, have searched the hotel and its surroundings from top to bottom for the last eighteen months.

Not once, but twice, does Monsieur G- and his team meticulously search the Minister’s hotel during the night while he is away. In the original story, they use the most advanced microscopes available and dismantle the furniture in an effort to locate the stolen letter. Their investigation is exhaustive — conducted with great precision both times. However, for someone as astute as the Minister, who is well aware that such thorough searches might occur, there is little reason to hide the letter in an obscure or overly intricate place.

In vain — although everyone can deduce from the situation that the Minister keeps the letter within reach.

Armed with this knowledge, Dupin—one of the two individuals Monsieur G- confides in, the other being the narrator—decides to meet with the Minister to find where the letter is hidden — which he believes is in an obvious place:

Dupin calls on the Minister. The latter receives him with studied nonchalance, affecting in his conversation romantic ennui.

Disguising his true intentions with casual conversation, Dupin engages the Minister in a relaxed conversation. However, Dupin’s primary focus remains on locating the letter. To ensure that the Minister cannot trace the direction of his gaze, Dupin wears glasses with green lenses, effectively masking his observations:

Meanwhile Dupin, whom this pretense does not deceive, his eyes protected by green glasses, proceeds to inspect the premises.

After looking around the room, Dupin finds a dirtied and folded piece of paper:

When his glance catches a rather crumpled piece of paper-apparently thrust carelessly into a division of an ugly pasteboard card rack, hanging gaudily from the middle of the mantelpiece — he already knows that he’s found what he’s looking for.

Thus, Dupin found the letter:

His conviction is reinforced by the very details which seem to contradict the description he has of the stolen letter, with the exception of the format, which remains the same.

In order to retrieve the letter, Dupin devises a plan:

Whereupon he has but to withdraw, after “forgetting” his snuffbox on the table, in order to return the following day to reclaim it-armed with a facsimile of the letter in its present state.

By deliberately “forgetting” his snuffbox at the Minister’s hotel, Dupin creates a plausible excuse to return days later, this time with a decoy letter prepared — one that is intentionally dirtied and folded to mimic the original. When he revisits the Minister, Dupin carefully orchestrates a distraction to carry out his plan.

As an incident in the street, prepared for the proper moment, draws the Minister to the window, Dupin in turn seizes the opportunity to snatch the letter while substituting the imitation and has only to maintain the appearances of a normal exit.

As the commotion outside — orchestrated by Dupin — unfolds on the street, the Minister leans out the window to investigate the disturbance. Taking advantage of the situation, Dupin discreetly swaps the real letter with his prepared decoy. In that moment, Dupin successfully steals the letter.

Lacan continues:

Here as well all has transpired, if not without noise, at least without any commotion.

At this juncture, the Minister has no idea that the letter is stolen and that Dupin was the one who stole it from him:

The quotient of the operation is that the Minister no longer has the letter, but far from suspecting that Dupin is the culprit who has ravished it from him, knows nothing of it.

Although it may seem that the Minister is left with nothing more than a worthless piece of paper, Lacan emphasizes the opposite: the letter still holds significant value. It is not just a mere scrap, but a symbolic reminder of the loss and the clever manipulation that has taken place. (Lacan will come back to this later):

Moreover, what [the Minister] is left with is far from insignificant for what follows.

Furthermore, Lacan points out that he will not delve into the reasons why Dupin chose to write a message in the decoy letter — at least not at this moment:

We shall return to what brought Dupin to inscribe a message on his counterfeit letter.

Without getting too specific, Lacan points out that what was written to the Minister reveals something crucial: the content of the message, with its specific tone and style, makes it unmistakable to the Minister that Dupin stole the letter:

Whatever the case, the Minister, when he tries to make use of it, will be able to read these words, written so that he may recognize Dupin’s hand:

… Un dessein si funeste / S’il n’est digne d’Atrée, est digne de Thyeste

whose source, Dupin tells us, is Crebillon’s Atrée

The English translation of the French quote above is: “A fatal design, if not worthy of Atreus, is worthy of Thyestes.” This line is cited from Prosper Jolyot de Crébillon’s Atrée, a five-act tragedy.

This marks the end of the second scene for Lacan.

Now that the two scenes have been laid out, Lacan continues by asking a rhetorical question:

Need we emphasize the similarity of these two sequences?

It is evident that in both scenes, a letter is stolen, however Lacan makes clear that the resemblance between the two goes beyond that:

Yes, for the resemblance we have in mind is not a simple collection of traits chosen only in order to delete their difference. And it would not be enough to retain those common traits at the expense of the others for the slightest truth to result.

Lacan is emphasizing that the resemblance between these two scenes goes beyond the simple fact that the letter was stolen. The deeper “truth” of these scenes is not found through a surface-level analysis and to employ a surface-level analysis would be to discard fruitful analysis. He continues:

It is rather the intersubjectivity in which the two actions are motivated that we wish to bring into relief, as well as the three terms through which it structures them.

Lacan highlights that the intersubjectivity — the way the characters’ actions are shaped by their relationships with one another — must be analyzed. It is not enough to simply observe the characters’ actions; one must also focus on their underlying intentions throughout the story along with their relationships with one another. There are three terms by which these actions and relations are structured:

The special status of these terms results from their corresponding simultaneously to the three logical moments through which the decision is precipitated and the three places it assigns to the subjects among whom it constitutes a choice.

To clarify, Lacan writes that the three terms are the result of a decision that has already been made, and they correspond to the logical moments through which the decision is reached:

That decision is reached in a glance’s time.

One might assume that the stealthily moves made by the Minister, the Prefect of Police, or Dupin play a large role, but Lacan does not find this to be the case.

For the maneuvers which follow, however stealthily they prolong it, add nothing to that glance, nor does the deferring of the deed in the second scene break the unity of that moment.

Also — not only do the stealthily moves not matter, but neither does Duping “deferring the deed” by taking time to craft a plan.

It is in this way that the glance defines and drives the plot.

Lacan continues by explaining what the three glances are:

[The third] glance presupposes two others, which it embraces in its vision of the breach left in their fallacious complementarity, anticipating in it the occasion for larceny afforded by that exposure.

Here, Lacan points out that the third glance depends on the two preceding glances and “embraces” the “fallacious complementarity” of the first two glances. To put simply, the third glance depends upon the Minister’s overconfidence in the imperceptiveness of the Prefect of Police. The Prefect’s blindness coupled with the Minister’s overconfidence seems to create a seemingly secure system. However, by exposing this fallacious complementarity, Dupin has an opening to exploit. Lacan makes clear that these three glances serve as an important part of our analysis:

Thus three moments, structuring three glances, borne by three subjects, incarnated each time by different characters.

So … what exactly are the three glances?

1. The first is a glance that sees nothing: the King and the police.

2. The second, a glance which sees that the first sees nothing and deludes itself as to the secrecy of what it hides: the Queen, then the Minister.

3. The third sees that the first two glances leave what should be hidden exposed to whoever would seize it: the Minister, and finally Dupin.

Between these subjects — the King and the police, the Queen and the Minister, and the Minister and Dupin — Lacan uses a metaphor to illustrate the dynamic between the three:

In order to grasp in its unity the intersubjective complex thus described, we would willingly seek a model in the technique legendarily attributed to the ostrich attempting to shield itself from danger; for that technique might ultimately be qualified as political, divided as it here is among three partners: the second believing itself invisible because the first has its head stuck in the ground, and all the while letting the third calmly pluck its rear; we need only enrich its proverbial denomination by a letter, producing la politique de l’autruiche, for the ostrich itself to take on forever a new meaning.

- Lacan’s phrase “la politique de l’autruiche” is a clever play on words. In French, autruche means “ostrich,” while autre translates to “other,” a core concept in Lacanian psychoanalysis.

To grasp the interrelation between the three glances, Lacan uses the metaphor of an ostrich. A popular misconception is that when an ostrich senses danger, it sticks its head in the sand, leaving itself unaware of its surroundings. Lacan applies this idea to the dynamics of the three glances, where each “glance” embodies a different position of awareness and misperception:

- In the first glance, the King and the Prefect of Police see nothing— they are completely blind to the existence or location of the letter. Like an ostrich with its head in the sand, they are oblivious to what is in front of them.

- In the second glance, the Queen and the Minister are aware that the first glance sees nothing and uses this to hide the letter. The Queen hides the letter from the King, believing that as long as the King remains blind, the secret is safe. Similarly, the Minister hides the letter in plain sight, confident that the Prefect of Police will not perceive it.

- In the third glance, Dupin — and the Minister in relation to the Queen — sees that the first two glances are ‘blind’. Dupin recognizes that the Prefect of Police’s methods and assumptions are flawed, and that the Minister’s confidence in his hiding spot relies on the Prefect’s blindness. Like the ostrich’s exposed rear, what the second glance thought was hidden is now open to exploitation.

Each glance depends on and reflects the limitations of the preceding one. Thus, the “ostrich” (autruche) metaphor applies to the failure of each subject to grasp the role of the Other in their endeavors to conceal and attain the letter. By solely focusing on their individual perspective, they lose sight of the complexities surrounding the situation.

Lacan continues:

Given the intersubjective modulus of the repetitive action, it remains to recognize in it a repetition automatism in the sense that interests us in Freud’s text.

As previously stated, Lacan’s ambitious goal is to thoroughly examine repetition automatism as it is situated within Freud’s framework. When Lacan refers to the “intersubjective modulus” of repetition automatism, he emphasizes that these repetitive actions are not merely internal psychological compulsions but are shaped by interactions between subjects. For Lacan, the focus is not on the repetitive actions themselves but on the underlying structure of the symbolic order that governs these interactions and determines the subject’s position within it. Furthermore:

The plurality of subjects, of course, can be no objection for those who are long accustomed to the perspectives summarized by our formula: the unconscious is the discourse of the Other.

Lacan speaks of the “plurality of subjects,” referring to the various characters in The Purloined Letter, such as the Queen, the King, the Minister, and Dupin. The actions of these subjects are not isolated but occur within a symbolic network that shapes their behavior. However, despite the presence of multiple subjects, the unconscious remains the discourse of the Other, meaning that the subject’s unconscious is governed by the symbolic order, not by personal will or isolated intentions. The unconscious operates through the external discourses and influences of the symbolic system, even if the subjects are unaware of these influences. Each subject’s actions are determined by this system: for example, the Queen hides the letter from the King, the Minister steals it from the Queen, Dupin steals it from the Minister. The repetitive nature of the letter’s theft and return reflects Lacan’s idea of repetition automatism: the symbolic order compels the subjects to repeat patterns of behavior, influenced by the structure of the Other.

Lacan continues:

And we will not recall now what the notion of the immixture of subjects, recently introduced in our reanalysis of the dream of Irma’s injection, adds to the discussion.

In this sentence, Lacan is referencing Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams published in 1899 — specifically the dream of Irma’s injection. In this text, Freud analyzes various elements of Irma’s dreams, including how different subjects are not isolated from one another but are instead interconnected through their interactions and shared experiences. Freud’s analysis points out that subjects are interlinked and mutually implicated, rather than existing in isolation. Lacan refers to this as the “immixture of subjects,” where the unconscious is shaped by the interplay between multiple subjects and their respective positions within a shared symbolic order — a network of meanings, language, social structures, and cultural norms.Lacan acknowledges that Freud’s work on this issue is significant but chooses not to elaborate further on it in this particular discussion.

Instead, Lacan focuses on something else:

What interests us today is the manner in which the subjects relay each other in their displacement during the intersubjective repetition.

Lacan’s interest lies in how the subjects in the story affect and prompt the actions of other characters. Through this intersubjective repetition, the subjects are impacted by displacement, where their emotions are unconsciously shifted or redirected. The repeated theft and concealment of the letter causes various emotional attachments to be displaced onto the letter itself, making the letter a symbolic object that channels their hidden anxieties. This displacement leads to shifts in the subjects’ roles and positions within the symbolic order, as their actions and relationships to the letter reveal deeper unconscious drives.

At this juncture, Lacan explicates:

We shall see that [the subjects’] displacement is determined by the place which a pure signifier — the purloined letter — comes to occupy in their trio.

Now, we have learned something important: the letter is a pure signifier. It is no longer just a physical object, but rather something that carries symbolic meaning. The contents of the letter are not important in this context — the subjects do not need to know what is inside the letter; it is the letter itself, as a signifier, that drives the actions and the subjects’ displacement. All of this constitutes repetition automatism:

And [this displacement] is what will confirm for us its status as repetition automatism.

Repetition automatism occurs when a pure signifier (like the purloined letter) drives the subject’s displacement.

Let us use the example of an individual compulsively checking to make sure the lock on their front door is secure.

The lock becomes a pure signifier, signifying more than just a symbol for security. The subject’s emotions — whether anxiety, insecurity, or fear — are displaced onto the lock. As a result, the act of checking the lock repeatedly becomes an automatic response to the unconscious emotional displacement, where the lock serves as a stand-in for the deeper emotional concerns the subject cannot fully address.

Lacan continues:

It does not, however, seem excessive, before pursuing this line of inquiry, to ask whether the thrust of the tale and the interest we bring to it — to the extent that they coincide — do not lie elsewhere.

Lacan suggests that we ought to consider whether the current interpretation of The Purloined Letter in relation to repetition automatism is sufficient. It is quite obvious that Lacan’s current interpretation of the story remains relatively surface level. Could there be another, deeper interpretation to uncover? Lacan asks:

May we view as simply a rationalization (in our gruff jargon) the fact that the story is told to us as a police mystery?

In this sentence, Lacan questions whether interpreting The Purloined Letter as a police mystery is simply a “rationalization,” offering a surface-level explanation of the story’s deeper significance. He further explains that many of the typical elements used in a standard police mystery are notably absent in The Purloined Letter:

In truth, we should be right in judging that fact highly dubious as soon as we note that everything which warrants such mystery concerning a crime or offense — its nature and motives, instruments and execution, the procedure used to discover the author, and the means employed to convict him — is carefully eliminated here at the start of each episode.

Let’s review each point that seems to be present but is, in fact, absent:

- Nature and motives: The contents of the letter are never revealed to the reader.

- Instruments and execution: This is somewhat odd since Dupin’s plan is detailed. Lacan may be pointing out that the actual theft is only briefly mentioned and not the primary focus of the story?

- The procedure used to discover the author: While there are steps taken to locate the letter, there is no real investigation into who actually stole it.

- The means employed to convict him: There is no conviction, as the Prefect simply takes the letter and leaves, without any formal resolution.

To continue, Lacan explains the general plot:

The act of deceit is, in fact, from the beginning as clearly known as the intrigues of the culprit and their effects on his victim. The problem, as exposed to us, is limited to the search for and restitution of the object of that deceit, and it seems rather intentional that the solution is already obtained when it is explained to us.

And, in a rather rhetorical manner, Lacan asks:

Is that how we are kept in suspense?

At the beginning of The Purloined Letter, the reader is immediately informed that the letter has been stolen and is made aware of its significant impact on the Queen’s situation. The reader is also told that the search and concealment of the letter have been ongoing. Lacan observes that by presenting all these facts upfront, the story intentionally avoids following the typical structure of a police mystery. Lacan acknowledges Poe’s earlier work and discusses how it contributed to the development of the police mystery genre:

Whatever credit we may accord the conventions of a genre for provoking a specific interest in the reader, we should not forget that “the Dupin tale” — this the second to appear — is a prototype, and that even if the genre were established in the first, it is still a little early for the author to play on a convention.

For those who may not be familiar, The Purloined Letter is the second short story by Poe featuring Dupin, the first being The Murders in the Rue Morgue, published in 1841. Lacan highlights that “the Dupin tale” serves as a prototype for the police mystery genre that would later become popular. However, Lacan argues that Poe’s work does not fit neatly into the genre and should not be interpreted as a typical police mystery. Although Lacan is cautioning us against interpreting this story as a general police mystery story, he also cautions us against other erroneous interpretations:

It would, however, be equally excessive to reduce the whole thing to a fable whose moral would be that in order to shield from inquisitive eyes one of those correspondences whose secrecy is sometimes necessary to conjugal peace, it suffices to leave the crucial letters lying about on one’s table, even though the meaningful side be turned face down.

Here, Lacan is pointing out the problem with interpreting The Purloined Letter as a simple fable or fairy tale. One might conclude the moral of the story to be that things which seem lost or hidden might actually be in plain sight, and overcomplicating the search is unnecessary. However, this interpretation oversimplifies the story, which holds much deeper meaning:

For [the fable interpretation] would be a hoax which, for our part, we would never recommend anyone try, lest he be gravely disappointed in his hopes.

Having established that there is a deeper meaning to the story, Lacan now outlines how one should approach its interpretation:

Might there then be no mystery other than, concerning the Prefect, an incompetence issuing in failure — were it not perhaps, concerning Dupin, a certain dissonance we hesitate to acknowledge between, on the one hand, the admittedly penetrating though, in their generality, not always quite relevant remarks with which he introduces us to his method and, on the other, the manner in which he in fact intervenes.

In this passage, Lacan argues that the true “mystery” in the story is not merely the Prefect’s failure to recover the letter. Instead, the mystery lies in Dupin’s method. Dupin’s comments on the case and his approach to retrieving the letter are vague, and there is a “dissonance” or inconsistency between his explanation of how he carried out his plan and the way he actually executed it. Essentially, Dupin’s intellectual brilliance and seemingly profound insights do not align with the simplicity of his actual actions in retrieving the letter.

Lacan continues:

Were we to pursue this sense of mystification a bit further we might soon begin to wonder whether, from that initial scene which only the rank of the protagonists saves from vaudeville, to the fall into ridicule which seems to await the Minister at the end, it is not this impression that everyone is being duped which makes for our pleasure.

If one were to continue exploring how to interpret the story, they might question whether the initial scene with the Queen and the Minister resembles something theatrical, even bordering on farcical, like a vaudeville play. The only thing that prevents us from fully viewing it this way is the high rank of the characters involved — they are figures of royalty and power, which lends the situation an air of seriousness. Furthermore, the “fall into ridicule” that awaits the Minister as Dupin outsmarts him to retrieve the letter is inevitable. Lacan suggests that while there may be moments where the story appears comedic or absurd, it remains a serious story. Much of the reader’s enjoyment comes from the way deception unfolds: the Queen is duped by the Minister, the Prefect is duped by his inability to locate the letter, and the Minister is duped by Dupin.

He further elaborates:

And we would be all the more inclined to think so in that we would recognize in that surmise, along with those of you who read us, the definition we once gave in passing of the modern hero, “whom ludicrous exploits exalt in circumstances of utter confusion.”

At this point, Lacan suggests that if one were to continue the line of reasoning established earlier, readers familiar with psychoanalytic literature might recognize Dupin as a “modern hero.” His heroism does not arise from grand actions but from his ability to draw seemingly simple conclusions in the midst of confusion and chaos. But might it be true that we ourselves may be getting tricked into thinking that Dupin is some kind of here? Lacan explicates:

But are we ourselves not taken in by the imposing presence of the amateur detective, prototype of a latter-day swashbuckler, as yet safe from the insipidity of our contemporary superman?

In this sentence, Lacan invites the reader to reconsider their perception of Dupin. While Dupin is portrayed as an “amateur detective” and a prototype of a “latter-day swashbuckler” (a romantic hero typical of adventure stories), his charisma and cunning might overshadow a more critical assessment of his character. Lacan contrasts Dupin with the idealized, flawless image of a modern “Superman,” suggesting that Dupin is a more nuanced, imperfect figure rather than a larger-than-life hero.

All of this contributes to the distinctive cleverness of The Purloined Letter:

A trick . . . sufficient for us to discern in this tale, on the contrary, so perfect a verisimilitude that it may be said that truth here reveals its fictive arrangement.

Lacan is arguing that the trickery in The Purloined Letter reveals a deeper meaning. The story begins with a convincing sense of reality (“verisimilitude”) that forces the reader to recognize the story as a deliberate work of fiction. Simultaneously, the story misleads the reader into thinking that the truth is found in the discovery of the letter. Lacan suggests that the real “truth” lies in how the story is constructed — how the story misdirects the reader’s expectations. In this sense, truth isn’t something clear or objective; it’s about how the narrative unfolds and influences what one thinks they know.

Lacan continues:

For such indeed is the direction in which the principles of that verisimilitude lead us.

He suggests that the convincing sense of reality (“versimilitude”) of the story allows for a deeper interpretation than solely a surface-level one, essentially restating his earlier thesis. Furthermore:

Entering into its strategy, we indeed perceive a new drama we may call complementary to the first, insofar as the latter was what is termed a play without words whereas the interest of the second plays on the properties of speech.

By closely analyzing the story’s structure, one can identify two distinct types of drama. The first revolves around a “play without words,” emphasizing the physical actions involved in the theft and concealment of the letter. The second focuses on the “properties of speech,” such as Dupin’s dialogue detailing how he cleverly recovered the letter. He explains:

If it is indeed clear that each of the two scenes of the real drama is narrated in the course of a different dialogue, it is only through access to those notions set forth in our teaching that one may recognize that it is not thus simply to augment the charm of the exposition, but that the dialogues themselves, in the opposite use they make of the powers of speech, take on a tension which makes of them a different drama, one which our vocabulary will distinguish from the first as persisting in the symbolic order.

Each part of the story — the two dramas — unfolds through “the course of different dialogues,” meaning that the first drama, centered on physical events, and the second drama, focused on Dupin’s intellectual explanations, are told in distinct ways. Lacan points out that this narrative structure is not merely designed to “augment the charm of the exposition,” suggesting that the story’s purpose goes beyond solely entertaining the reader. Instead, the two dialogues, grounded in opposing uses of speech — one descriptive and one interpretive — create a tension. This tension gives rise to a new kind of drama, one that exists and persists within the symbolic order.

Lacan further elaborates by focusing on the first dialogue:

The first dialogue — between the Prefect of Police and Dupin — is played as between a deaf man and one who hears.

By using the metaphor of the Prefect as deaf and Dupin as the “one who hears,” Lacan isolates the complexities of communication:

That is, it presents the real complexity of what is ordinarily simplified, with the most confused results, in the notion of communication.

Communication might appear straightforward, but Lacan emphasizes how confusion and misdirection arise through the characters’ dialogue. Effective communication involves more than just hearing what someone says — it requires a deeper understanding of the underlying meanings. To reiterate:

This example demonstrates indeed how an act of communication may give the impression at which theorists too often stop: of allowing in its transmission but a single meaning, as though the highly significant commentary into which he who understands integrates it, could, because unperceived by him who does not understand, be considered null.

Many individuals — including theorists — often view communication as a straightforward exchange where a single, clear meaning is transmitted from one person to another. Lacan critiques this simplistic perspective, arguing that true understanding, as exemplified by Dupin, involves integrating one’s own interpretative commentary into the conversation. This interpretive commentary often goes unnoticed by those who have not mastered the nuances of communication.

Further still:

It remains that if only the dialogue’s meaning as a report is retained, its verisimilitude may appear to depend on a guarantee of exactitude.

Here, Lacan observes that interpreting the dialogue solely as a factual report might lead one to mistakenly think that the story’s realism depends entirely on its factual accuracy. Lacan writes:

But here dialogue may be more fertile than it seems, if we demonstrate its tactics: as shall be seen by focusing on the recounting of our first scene.

Lacan suggests that the dialogue in the story can be understood better if one moves past a surface-level reading. He emphasizes that by carefully examining the “tactics” used in the dialogue, particularly in the first scene, one can uncover a deeper meaning. Lacan explains:

For the double and even triple subjective filter through which that scene comes to us: a narration by Dupin’s friend and associate (henceforth to be called the general narrator of the story) of the account by which the Prefect reveals to Dupin the report the Queen gave him of it, is not merely the consequence of a fortuitous arrangement.

The setup of the first scene is framed through a “double and even triple subjective” lens, as it is relayed from multiple perspectives before reaching the reader. The reader encounters the narrator presenting the story, followed by the Prefect recounting the issue at hand, who, in turn, received the initial information from the Queen. Thus, the narrator is not directly conveying the events as they happened, but rather recounting them through various layers of perspective.

Lacan continues:

If indeed the extremity to which the original narrator is reduced precludes her altering any of the events, it would be wrong to believe that the Prefect is empowered to lend her his voice in this case only by that lack of imagination on which he has, dare we say, the patent.

The original narrator of the events is the Queen, but it would be foolish to think that the Prefect can perfectly “lend her his voice.” This is because the Prefect lacks imagination and creativity — traits that he is notably deficient in (these traits are his “patent”). Thus, as the message of events is passed from the Queen to the Prefect, then from the Prefect to Dupin and the story’s narrator, and finally from the narrator to the reader:

The fact that the message is thus retransmitted assures us of what may by no means be taken for granted: that it belongs to the dimension of language.

Lacan makes clear that this message “belongs to the dimension of language.” Hence, it is evident that this story has a clear relationship to the symbolic order, with the letter being a pure signifier. Let’s continue:

Those who are here know our remarks on the subject, specifically those illustrated by the countercase of the so-called language of bees: in which a linguist can see only a simple signaling of the location of objects, in other words: only an imaginary function more differentiated than others.

At this point, Lacan distinguishes between two forms of communication: the language of bees and human language. Linguists view bee communication as a simple signaling of the location of objects, a functional act that serves an “imaginary” purpose — focused on direct, practical interaction rather than symbolic meaning. Human language, however, is deeply symbolic, where objects and ideas are represented by signs that go beyond their immediate function. Human language is distinguished by its ability to submit natural objects to the complexity of symbols, which evokes meanings beyond the immediate. However, not all human language is dissimilar to bees:

We emphasize that such a form of communication is not absent in man, however evanescent a naturally given object may be for him, split as it is in its submission to symbols.

While humans can communicate in a manner similar to bees, the key difference is that humans take the world around them and transform it into various symbols, which adds layers of meaning beyond the immediate, practical communication seen in bees.

To further elaborate:

Something equivalent may no doubt be grasped in the communion established between two persons in their hatred of a common object: except that the meeting is possible only over a single object, defined by those traits in the individual each of the two resists.

When two individuals unite in hatred of an object, that object is defined by traits each person opposes. Similar to the earlier case of communication about a shared, desired object, this connection is also formed through a shared rejection of an object, rather than attraction.

But such communication is not transmissible in symbolic form. It may be maintained only in the relation with the object.

When two individuals unite over their shared hatred of an object, the communication around this hatred cannot be expressed symbolically. Instead, it is maintained solely through each individual’s direct relationship with the object they both reject. Furthermore:

In such a manner it may bring together an indefinite number of subjects in a common “ideal”: the communication of one subject with another within the crowd thus constituted will nonetheless remain irreducibly mediated by an ineffable relation.

Lacan is explaining that when individuals have a shared goal, belief, or ideal, they have the ability to be drawn into a crowd. However, even when they are all galvanized around the same thing — whether it be something one is for or against — Lacan still finds this communication to be mediated by something that cannot be fully expressed (“an ineffable relation”). Though individuals share a common ideal, the way that they relate to that ideal is uniquely personal and cannot be easily put into words. Lacan continues by addressing a common criticism of his theorizations:

This digression is not only a recollection of principles distantly addressed to those who impute to us a neglect of nonverbal communication: in determining the scope of what speech repeats, it prepares the question of what symptoms repeat.

Some critics argue that Lacan overlooks non-verbal communication, but his use of the bee example shows that he does address it. However, his primary focus here is on speech and verbal communication, particularly its repetitive nature, which ties into the theme of repetition automatism central to this seminar. By analyzing the symbolic structure of language and its repetition, Lacan prepares the ground for understanding how symptoms — unconscious patterns in behavior or thought — repeat in similar ways. Lacan explains:

Thus the indirect telling sifts out the linguistic dimension, and the general narrator, by duplicating it, “hypothetically” adds nothing to it.

As seen in the first dialogue, where the narrator indirectly recounts the events from the Prefect’s perspective, the “linguistic dimension” becomes oversimplified, as the narrator adds nothing new to the overall structure or interpretation of the events. However, the linguistic dimension is not just present in the first dialogue:

[The linguistic dimension’s] role in the second dialogue is entirely different.

The difference between these two dialogues is striking:

For the [second dialogue] will be opposed to the first like those poles we have distinguished elsewhere in language and which are opposed like word to speech.

Lacan contrasts these dialogues as polar opposites, similar to the difference between an individual word and speech. He suggests that the second dialogue is more dynamic, while the first is more fixed:

Which is to say that a transition is made here from the domain of exactitude to the register of truth.

The first dialogue, focused on the rigidity of the word, aligns with a “domain of exactitude,” where a fixed meaning is derived, while the second dialogue is centered on an interpretive understanding of truth. Lacan writes:

Now [the register of truth]— we dare think we needn’t come back to this — is situated entirely elsewhere, strictly speaking at the very foundation of intersubjectivity.

Here, Lacan notes that the register of truth does not need further explanation because it lies “at the very foundation of intersubjectivity.” Truth, in this context, is rooted in how individuals relate to one another rather than a fixed meaning. So … where is the register of truth located?

[The register of truth] is located there where the subject can grasp nothing but the very subjectivity which constitutes an Other as absolute.

Lacan emphasizes that the register of truth emerges where a subject encounters the subjectivity of another, referred to as the “Other.” This “Other” is described as “absolute,” indicating that another’s subjectivity is beyond the full comprehension of the subject. Truth is not concerned with objective facts — it is about the relations between subjects. To make this point clear, Lacan tells a joke:

We shall be satisfied here to indicate its place by evoking the dialogue which seems to us to merit its attribution as a Jewish joke by that state of privation through which the relation of signifier to speech appears in the entreaty which brings the dialogue to a close: “Why are you lying to me?” one character shouts breathlessly. “Yes, why do you lie to me saying you’re going to Cracow so I should believe you’re going to Lemberg, when in reality you are going to Cracow?”

In this Jewish joke, one that belongs to self-referential humor to people of the Jewish culture, Lacan highlights the paradoxical nature between the signifier (language) and speech (how this language was communicated). This joke centers on a misunderstanding:

- Character One asks Character Two why they are lying about going to Cracow, as if Character Two is trying to make Character One believe they are going to Cracow instead of Lemberg. However, Character One immediately contradicts themselves by saying that Character Two is actually going to Cracow.

- Now, Character Two is put in a tricky position because if they admit they are going to Cracow, it seems like they are admitting to lying about it to trick Character One into thinking that they were actually going to Lemberg— when, in fact, they were never lying about their destination in the first place. It creates a paradox where Character Two is falsely accused of lying, even though they haven’t.

Lacan continues his analysis:

We might be prompted to ask a similar question by the torrent of logical impasses, eristic enigmas, paradoxes, and even jests presented to us as an introduction to Dupin’s method if the fact that they were confided to us by a would-be disciple did not endow them with a new dimension through that act of delegation.

When the Prefect presents all sorts of barriers to capturing the letter, Dupin’s highly analytical method for solving them comes across as somewhat brilliant — and the reader learns about this through a “would-be disciple” (presumably the narrator, who is learning from Dupin). The mention of “delegation” refers to the narrator being assigned the task of conveying this information to the reader. To carry on:

Such is the unmistakable magic of legacies: the witness’s fidelity is the cowl which blinds and lays to rest all criticism of his testimony.

Lacan shifts the focus to legacies—how traditions, knowledge, and culture are handed down. The “witness” in this context is someone who preserves or testifies to a legacy, showing loyalty to it. The word “cowl,” typically referring to a hood worn during religious ceremonies, is used by Lacan as a metaphor. It suggests that those who remain faithful to a legacy are blind to its criticisms, unable to perceive alternative perspectives. He asks:

What could be more convincing, moreover, than the gesture of laying one’s cards face up on the table?

This rhetorical question is particularly impactful when considering that in The Purloined Letter, the Minister lays all his cards face up on the table. While this is quite apparent, it’s important to note that this passage specifically refers to Dupin’s method: by the end of the story, Dupin reveals his entire plan. Lacan uses this scenario as an analogy to a magic trick:

So much so that we are momentarily persuaded that the magician has in fact demonstrated, as he promised, how his trick was performed, whereas he has only renewed it in still purer form: at which point we fathom the measure of the supremacy of the signifier in the subject.

As Dupin explains his plan to retrieve the letter, it feels as though a magic trick has been performed and revealed by the end of the story. The reader experiences that “a-ha!” moment when the mechanics of the trick are finally explained. However, while the reader learns the details of the trick, they do not fully understood how it unfolded; this is akin to a magician showing you a trick a lot slower. Even though one might think they grasp the entire method, what they are truly conceptualizing is not the trick itself, but how it was executed — meaning the method of the reveal, rather than the deeper, underlying trick that continues to operate beneath the surface.

Lacan continues:

Such is Dupin’s maneuver when he starts with the story of the child prodigy who takes in all his friends at the game of even and odd with his trick of identifying with the opponent, concerning which we have nevertheless shown that it cannot reach the first level of theoretical elaboration; namely, intersubjective alternation, without immediately stumbling on the buttress of its recurrence.

- This may very well be a reference to the game that Freud played with his grandson.

At this point in the seminar, Lacan refers to a moment when Dupin explains the game of “even and odd,” played by a child prodigy. In this game, one player is designated “even” and the other “odd.” The players count to three, similar to rock, paper, scissors, and then each puts out between 0–5 fingers. The players then add their fingers together. For example, if one player puts out one finger and the other puts out three, the sum would be four. Since the sum is even, the “even” player earns a point. In Dupin’s analysis of the child prodigy, the child observes the opponent’s facial expressions to deduce the number they might be thinking of, based on the emotions displayed on their face. After guessing the opponent’s number, the child then selects a number to play that will ensure they score the point. This trick by the child relies on a repetitive cycle of observing one’s opponent and reacting — nothing more. Lacan writes:

We are all the same treated — so much smoke in our eyes — to the names of La Rochefoucauld, La Bruyère, Machiavelli, and Campanella, whose renown, by this time, would seem but futile when confronted with the child’s prowess.

Lacan find’s the intellectual genius of the child quite astounding, comparing this child’s cunning to the likes of brilliant authors, philosophers, and political strategists. Furthermore:

Followed by Chamfort, whose maxim that “it is a safe wager that every public idea, every accepted convention is foolish, since it suits the greatest number” will no doubt satisfy all who think they escape its law, that is, precisely, the greatest number.

Lacan cites French writer Nicolas Chamfort’s famous quote, which suggests that if an idea is collectively accepted or deemed correct by the majority, then that idea is likely foolish because it caters to the masses, who are themselves misguided. In this context, the child prodigy in the game “even and odd” taps into the predictable emotional reactions of his opponent, which align with a majority response. By reading the opponent’s face, the child manipulates these general, often unconscious, reactions, much like how a majority-driven idea can rely on simple, conventional patterns that may lack deeper insight.

Lacan explicates:

That Dupin accuses the French of deception for applying the word analysis to algebra will hardly threaten our pride since, moreover, the freeing of that term for other uses ought by no means to provoke a psychoanalyst to intervene and claim his rights.

Dupin criticizes the French for applying the term “analysis” to “algebra,” arguing that it complicates the true meaning of analysis by associating it with a mathematical discipline. Lacan remarks that the French are unlikely to be offended by this, as they are protective of their intellectual traditions. As a psychoanalyst, Lacan emphasizes that the term “analysis” is not exclusive to any one field or discipline (psycho “analysis”). Might Lacan be making an implicitly argument regarding the flexibility of language here? At any rate:

And there [Dupin] goes making philological remarks which should positively delight any lovers of Latin: when he recalls without deigning to say anymore that ambitus doesn’t mean ambition, religio, religion, homines honesti, honest men,” who among you would not take pleasure in remembering… what those words mean to anyone familiar with Cicero and Lucretius. No doubt Poe is having a good time…

Lacan notes the philological claims made by Dupin. If unaware, philology is the study of language throughout ancient historical texts. Dupin purposefully uses outdated language without further elaborating on them, showing his cleverness:

- “Ambitus doesn’t mean ambition”: In Latin, ambitus refers to seeking favor, usually in the context of political gain which is different than how we understand ambition today.

- “Religio doesn’t mean religion”: In Latin, religio had a broader meaning than religion in that it meant general conscientiousness in the context of a duty or obligation toward something virtuous.

- “Homines honesti doesn’t mean honest men”: The Latin phrase homines honesti refers to general virtuousness, no just honesty.

These are important Easter eggs in The Purloined Letter that Lacan suggests would be appreciated by readers of Latin — and by those familiar with Roman philosophers like Cicero and Lucretius. As Lacan points out, Poe seems to be enjoying himself with these intricate, subtle shifts in meaning that might go unnoticed by the average reader.

Lacan asks a few rhetorical questions:

But a suspicion occurs to us: Might not this parade of erudition be destined to reveal to us the key words of our drama? Is not the magician repeating his trick before our eyes, without deceiving us this time about divulging his secret, but pressing his wager to the point of really explaining it to us without us seeing a thing?

Here, Lacan suggests that Dupin’s intellectual prowess and the references he makes may not be just for show. Instead, Dupin might be deliberately using this language to convey something deeper. While Dupin explains how his “trick” was performed — much like a magician revealing the secret behind a trick — the real question is whether the reader truly grasps it. For example, might there another layer to the trick, hidden right under the reader’s nose, just as the letter was in plain sight of the Prefect but he couldn’t see it? He writes:

That would be the summit of the illusionist’s art: through one of his fictive creations to truly delude us.

Thus, the greatest achievement an illusionist can attain is to deceive the audience to such an extent that they are unaware they are being tricked. With magic tricks, it’s typically clear to the audience that a trick is happening. However, in the case of The Purloined Letter, the reader is deceived into believing that they are no longer being tricked and that they have fully grasped Dupin’s method, when in fact, the trick is still at play. Lacan asks:

And is it not such effects which justify our referring, without malice, to a number of imaginary heroes as real characters?

In the same way that an audience might not realize a trick is happening, various fictional characters in media — whether in literature, movies, etc. — are often treated as if they were legitimate historical figures. Similarly, Dupin’s character blurs the line between illusion and reality for the reader. This leads the reader to accept Dupin’s method without scrutiny, viewing him as a brilliant, trustworthy detective. In doing so, Dupin, or rather, Poe, creates an illusion, convincing the reader of his expertise and understanding while potentially hiding a deeper trick. Furthermore:

As well, when we are open to hearing the way in which Martin Heidegger discloses to us in the word aletheia the play of truth, we rediscover a secret to which truth has always initiated her lovers, and through which they learn that it is in hiding that she offers herself to them most truly.

Lacan references 19th-century German philosopher Martin Heidegger’s concept of aletheia, which doesn’t simply mean truth, but rather highlights how what is hidden can be revealed. This, as I understand it, contrasts with Heidegger’s idea of Gestell, which represents a way of concealing truth. When Lacan refers to the “lovers” of truth, he suggests that understanding truth requires a deep, engaged relationship with it, much like a lover who seeks to truly understand the person they love.

Lacan elaborates:

Thus even if Dupin’s comments did not defy us so blatantly to believe in them, we should still have to make that attempt against the opposite temptation.

Lacan suggests that Dupin’s explanation may not necessarily aim for validation or approval, but because of his intellectual charm, we are inclined to accept his reasoning without question. However … should the reader just accept this? If the reader walks away assuming that Dupin told the truth, the reader very well may have been tricked.

Lacan elucidates:

Let us track down (dépistons) [Dupin’s] footprints there where they elude (dépiste) us. And first of all in the criticism by which he explains the Prefect’s lack of success.

In this sentence, Lacan plays with the French words “dépistons” (to track down) and “dépiste” (to evade), creating a paradox: the act of searching for something that actively resists being found. This emphasizes that Dupin’s method is not straightforward or easily mapped out, reflecting its complexity and the difficulty of fully grasping it. Lacan continues:

We already saw it surface in those furtive gibes the Prefect, in the first conversation, failed to heed, seeing in them only a pretext for hilarity.

Lacan starts by highlighting Dupin’s criticism of the Prefect’s failure to find the letter. Through subtle “furtive gibes” or light mockery, Dupin hints at the Prefect’s mistakes, but the Prefect fails to notice them. Instead of recognizing these as critiques of his approach, the Prefect dismisses them entirely. In reality, Dupin’s comments were strategically stated to the Prefect:

That it is, as Dupin insinuates, because a problem is too simple, indeed too evident, that it may appear obscure, will never have any more bearing for him than a vigorous rub of the ribcage.

Dupin argues that this problem is so simple to solve that it appears odd and obscure. When Lacan says that this issue has no more bearing than a “vigorous rub of the ribcage” he is saying that a slight touch on the rib cage is hardly noticeable in the same way that the simplicity of the situation is. The Prefect is made to not be intelligent:

Everything is arranged to induce in us a sense of the character’s imbecility.

This is further explained by the Prefect’s description of his efforts:

Which is powerfully articulated by the fact that he and his confederates never conceive of anything beyond what an ordinary rogue might imagine for hiding an object-that is, precisely the all too well known series of extraordinary hiding places: which are promptly cataloged for us, from hidden desk drawers to removable tabletops, from the detachable cushions of chairs to their hollowed-out legs, from the reverse side of mirrors to the “thickness” of book bindings.

In The Purloined Letter, the Prefect and his team employ various investigative methods, even using the finest microscopes to meticulously search the Minister’s residence — not just once, but twice. Furthermore:

After which, a moment of derision at the Prefect’s error in deducing that because the Minister is a poet, he is not far from being mad, an error, it is argued, which would consist, but this is hardly negligible, simply in a false distribution of the middle term, since it is far from following from the fact that all madmen are poets.

The Prefect commits a logical fallacy in his reasoning. He assumes the premise that all madmen are poets and incorrectly deduces that all poets must be madmen. As a result, he concludes that the Minister, being a poet, would have hidden the letter in an elaborate and ingenious way (at least more ingenious than leaving the letter out in the open).

At any rate, Lacan continues:

Yes indeed. But we ourselves are left in the dark as to the poet’s superiority in the art of concealment — even if he be a mathematician to boot — since our pursuit is suddenly thwarted, dragged as we are into a thicket of bad arguments directed against the reasoning of mathematicians, who never, so far as I know, showed such devotion to their formulae as to identify them with reason itself.

The Prefect is depicted as believing that the Minister possesses a unique skill in the “art of concealment” because he is a poet, and possibly even a mathematician. This belief stems from the Prefect’s assumptions about poets and mathematicians, particularly the idea that they are inherently clever. Lacan points out that even mathematicians recognize that their formulas do not equate to pure reason itself. Lacan further elaborates:

At least, let us testify that unlike what seems to be Poe’s experience, it occasionally befalls us — with our friend Riguet, whose presence here is a guarantee that our incursions into combinatory analysis are not leading us astray — to hazard such serious deviations (virtual blasphemies, according to Poe) as to cast into doubt that “x2 + px is perhaps not absolutely equal to q,” without ever — here we give the lie to Poe — having had to fend off any unexpected attack.

In this passage, Lacan highlights the difference between Poe’s approach to intellectual pursuits and his own. Poe seems to adhere strictly to established meanings and logical consistency, while Lacan is more open to taking intellectual risks. To support this approach, Lacan introduces Jacques Riguet, a French mathematician, whose work provides a grounded mathematical foundation for these intellectual risks. While Poe might view such risks as “blasphemous,” Lacan points out that even well-established mathematical truths, such as x² + px = q, can be questioned. Despite the potential for challenging these norms, Lacan argues that such questioning does not lead to the kinds of attacks that Poe might anticipate.

To continue:

Is not so much intelligence being exercised then simply to divert our own from what had been indicated earlier as given, namely, that the police have looked everywhere: which we were to understand-vis-à-vis the area in which the police, not without reason, assumed the letter might be found-in terms of a (no doubt theoretical) exhaustion of space, but concerning which the tale’s piquancy depends on our accepting it literally?

Lacan questions whether the police’s intelligence is truly significant or merely a way to mislead the reader. While the police conduct a thorough and methodical search — an undeniably logical approach — their exhaustive efforts create the illusion that they have genuinely searched every part of the premises. The “piquancy,” or the irony and sharpness of the story, hinges on whether the reader takes this claim of completeness at face value. Perhaps true intelligence lies not in adhering to the police’s framework but in stepping outside it to view the situation from a fresh perspective. To be fair, however, the police truly conducted a thorough search:

The division of the entire volume into numbered “compartments,” which was the principle governing the operation, being presented to us as so precise that “the fiftieth part of a line,” it is said, could not escape the probing of the investigators.

The Minister’s premises were divided into sections, with each one meticulously examined down to “the fiftieth part of a line,” signifying that the investigators were so precise they scrutinized even the smallest detail to a fractional level. Lacan continues:

Have we not then the right to ask how it happened that the letter was not found anywhere, or rather to observe that all we have been told of a more far-ranging conception of concealment does not explain, in all rigor, that the letter escaped detection, since the area combed did in fact contain it, as Dupin’s discovery eventually proves?

Here, Lacan challenges us to question how the police failed to find the letter despite their thorough investigation. We were led to believe that the letter must have been hidden in a complex and elaborate manner, beyond the scope of the search. However, this explanation doesn’t hold up, as the letter should have been found given the extent of their efforts. The paradox Lacan raises is that while the police searched the area where the letter was hidden, they failed to find it due to their limited perspective. The letter was right in front of them, but they couldn’t see it. Furthermore:

Must a letter then, of all objects, be endowed with the property of nullibiety: to use a term which the thesaurus known as Roget picks up from the semiotic utopia of Bishop Wilkins?