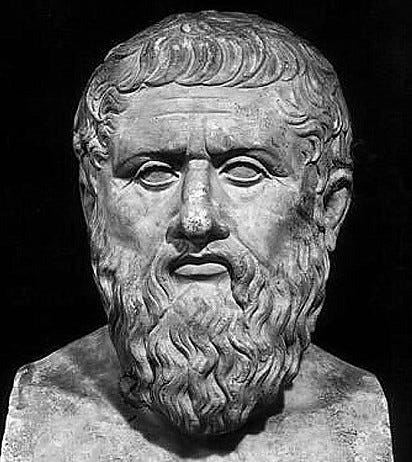

Examining one of political theory’s most beloved texts

Plato’s Republic, penned over two millennia ago, is undeniably one of the most profound and enduring texts in the realm of philosophy, casting a towering shadow over the intellectual landscape for centuries. As a dedicated student of political science, I have encountered The Republic numerous times in the diverse and thought-provoking courses on political theory that have shaped my academic journey. These encounters have fostered within me a profound appreciation for Plato’s work, even though many of the contemporary philosophers I align with tend to dismiss the tenets of Platonism. Nevertheless, The Republic’s significance as one of the earliest and most foundational texts in political theory cannot be overstated.

The objective of this blog is to dissect Book One of Plato’s Republic, making its content more accessible while providing valuable insights into the meanings one can derive from this foundational text.

**Citation Note: The citation for this text is at the bottom of the blog post

Book One

a) Polemarchus confronts Socrates and Glaucon

The story commences with Socrates and his companion Glaucon, the son of Ariston. They are approached by a slave boy who has been sent to them by Polemarchus, the son of Cephalus. The slave boy conveys Polemarchus’ instruction to Socrates and Glaucon, saying, “Polemarchus orders you to wait.” In response, Socrates asks the slave boy where his master is. The slave boy responds, indicating that Polemarchus is “coming up behind” them. Glaucon promptly replies, “Of course, we’ll wait” (3).

Polemarchus, accompanied by his men, approaches Socrates and Glaucon. He begins by suggesting that Socrates and Glaucon might be in a hurry to head into town. Socrates responds facitiously, saying, “That’s not a bad guess.” However, Polemarchus then immediately asks Socrates a rhetorical question, saying, “Do you see how many of us there are?” (3). This question is a thinly veiled threat, implying that if Socrates and Glaucon didn’t stay and comply with Polemarchus’ wishes, his strong friends would use force to ensure they stayed.

One line that captivates my attention and appears to foreshadow events is Polemarchus’ response to Socrates when Socrates suggests, “Is there not still another possibility? That we should convince you that you must let us go?” Polemarchus retorts, “Could you truly convince us if we didn’t listen?” (3). This exchange of dialogue seems to hint at the course of Socrates’ subsequent questioning later on in the chapter, ultimately leading to Polemarchus conceding to Socrates’ arguments; though, Polemarchus does not actually ‘listen’ to Socrates’ and falls victim to Socrates’ definition of justice (this will be explored later).

At any rate, Glaucon promptly states, “It seems we must stay” (4). And so, Socrates and Glaucon follow Polemarchus.

Quick note on Glaucon: The Greek word glaukoma, meaning “opacity of the lens,” has the prefix glaukos. This is the same prefix used in Glaucon’s name. Throughout The Republic, Glaucon is found to not fully grasp some of Socrates’ arguments (i.e., he is not able to ‘see’ or understand the arguments presented by Socrates). Glaucon’s swift response to Polemarchus might suggest his inclination to follow the lead of others because he relies on someone else to guide him, given his inability to see independently.

b) Socrates and Cephalus

Upon their arrival at Polemarchus’ house, Socrates, Glaucon, and Polemarchus, along with their group of companions, encounter Polemarchus’ father, Cephalus. Cephalus speaks with Socrates and makes an intriguing remark, suggesting that in his old age, “the desires and pleasures that have to do with speeches grow the more” (4). This statement appears to carry a subtle undertone, possibly alluding to Socrates’ earlier reluctance to engage in conversation with Polemarchus and his friends. While Cephalus may not be aware of Socrates’ initial hesitation, he might sense Socrates’ wisdom or experience in this regard.

Cephalus continues by advising Socrates: “Now do as I say: be with these young men, but come here regularly to us as to friends and your very own kin” (4). This advice seems to draw a dichotomy between Socrates’ role with the young men, resembling that of a teacher or mentor, and his relationship when visiting Cephalus’ home, where he is treated more like a close friend or family member.

In response, Socrates expresses his eagerness to engage in discussions with the elderly, stating that he is “delighted to discuss with the very old” (4). He justifies this enthusiasm by likening the elderly to individuals who have traversed a path in life that the younger generation may eventually travel. For Socrates, there is valuable wisdom to be gained from the experiences of those who have walked this path before, and he asserts, “one ought, in my opinion, to learn from them” (4).

Cephalus proceeds to elaborate on the common perspective that many people, as they age, “lament longing for the pleasures of youth,” which encompass activities such as sexual intercourse, drinking parties, and feasts (5). Additionally, some older individuals bemoan the mistreatment they may endure from their own family members during their later years. Yet, Cephalus vehemently opposes this prevailing view. He asserts that old age does not inherently lead to such lamentation or complaints, citing his own contentment as an example. According to Cephalus, old age brings about a profound sense of peace and freedom from the fleeting indulgences of youth. He values the character and inner qualities of men far more than the temporary pleasures of youth.

Socrates, upon hearing Cephalus’ perspective, expresses his amazement and suggests that he assumes “many do not accept” Cephalus’ words. Instead, Socrates argues that many people are inclined to believe that Cephalus’ ability to bear old age with ease is not necessarily attributed to his character but rather to his possession of wealth. Socrates raises an interesting point that Cephalus may be perceived by others as having an easier time with old age due to financial security and resources.

Cephalus responds to Socrates with the story of Themistocles:

“When a Seriphean abused [Themistocles] — saying that he was illustrious not thanks to himself but thanks to the city — he answered that if he himself had been a Seriphean he would not have made a name, nor would that man have made one had he been an Athenian. And the same argument also holds good for those who are not wealthy and bear old age with difficulty: the decent man would not bear old age with poverty very easily, nor would the one who is not a decent sort ever be content with himself even if he were wealthy.” (5–6)

Cephalus’ point in this context is that while he acknowledges the advantages of wealth in making certain aspects of old age more comfortable, he firmly believes that one’s character and moral values play a more significant role in determining one’s overall well-being during the aging process. In Cephalus’ view, old age can pose difficulties for individuals who are poor but of good character. Nevertheless, their experience is still more positive compared to those who lack both wealth and good character. Similarly, even among the rich, the absence of moral goodness results in unhappiness during old age. Thus, Cephalus concludes the primacy of moral character over wealth.

Following this, Socrates poses a question to Cephalus — “What do you suppose is the greatest good that you have enjoyed from possessing great wealth?” (6). Cephalus responds by discussing the intricate relationship between wealth and mortality. He articulates that as a person approaches the end of their life, “fear and care enter him for things to which he gave no thought before” (6). This heightened awareness is attributed to the narrative of Hades, where older individuals must now contemplate being responsible for their actions while they were alive.

Cephalus continues by arguing that attaining great wealth “contributes a great deal to not cheating or lying to any man against one’s will” (7). He contends that accumulating wealth prompts individuals to abstain from actions that would typically be out of character — such as resorting to theft of bread when faced with hunger. To provide another example from Cephalus, the possession of money enables individuals to avoid finding themselves in a situation where they owe someone an amount they may struggle to repay:

The possession of money contributes a great deal to not cheating or lying to any man against one’s will, and, moreover, to not departing for that other place frightened because one owes some sacrifices to a god or money to a human being. (7)

At any rate, Socrates is concerned with justice and continues to refute Cephalus’ views of justice:

Everyone would surely say that if a man takes weapons from a friend when the latter is of sound mind, and the friend demands them back when he is mad, one shouldn’t give back such things. (7)

Consider a scenario in which a friend succumbs to madness and poses a threat to themselves or others with their weapons. Socrates argues that acting justly in this situation would involve taking those weapons, even if it entails deceiving your friend about the action.

On this point, Cephalus agrees: “What you say is right” (7).

Therefore, Socrates concludes Cephalus’ definition of justice to be erroneous. “Then this isn’t the definition of justice,” Socrates says, “speaking the truth and giving back what one takes” (7). But before Cephalus could respond, Polemarchus interrupts, disagreeing with Socrates.

“I hand down the argument to you,” Cephalus tells Polemarchus, “for it is time for me to look after the sacrifices.” Polemarchus responds, “Am I not the heir of what belongs to you?” to Cephalus. Cephalus responds to Polemarchus, “Certainly” and laughs while leaving.

c) Socrates and Polemarchus

Polemarchus begins his argument by asserting that Simonides is correct about justice. Socrates asks, “What was it Simonides said about justice that you assert he said correctly?” (7).

Polemarchus responds: “That it is just to give to each what is owed” (7).

Yet, Polemarchus concedes that Simonides’ definition of justice does not entail returning a friend’s weapons when they are unsound mind. For “[Simonides] supposes that friends owe it to friends to do some good and nothing bad” (8).

“Must we give back to enemies whatever is owed to them?” Socrates asks (8).

Polemarchus responds arguing “ that an enemy owes his enemy the very thing which is also fitting: some harm” (8).

As Socrates officially conceptualizes the entire stance of Polemarchus’ definition of justice, he asks a series of questions to Polemarchus regarding what is owed:

“The art of medicine gives what that is owed and fitting to which things?”

“Drugs, foods and drinks to bodies.”

“The art called cooking gives what that is owed and fitting to which things?”

“Seasonings to meats”

“Now then, the art that gives what to which things would be called justice?”

“The one that gives benefits and harms to friends and enemies.”

(8; emphasis mine)

Therefore, Polemarchus’ definition of justice is as followed: “Doing good to friends and harm to enemies” (8).

Socrates continues his series of questions:

“With respect to disease and health, who is most able to do good to sick firends and bad to enemies?”

“A doctor.”

“And with respect to the danger of the sea, who has this power over those who are sailing?”

“A pilot.”

(8–9)

Finally, Socrates asks:

“What about the just man — in what action and with respect to what work is he most able to help friends and harm enemies?” Polemarchus responds by arguing that the just person takes the actions in “making war and being an ally in battle” (9).

The next set of questions Socrates asks Polemarchus concerns the usefulness of a just person. For example, to people who are not sick, a doctor is useless. Or to people who are not sailing, a pilot is useless. Therefore, Socrates takes issue with the just man “making war and being an ally in battle” as this would be useless to someone not involved in warfare. However, Polemarchus contends that just men are still useful in peacetime — particularly for the acquisition of partnerships.

Yet, Socrates continues to question the type of partnerships the just person is useful for. If the just person forms a partnership with a skilled housebuilder, their usefulness to the housebuilder is evidently nullified if the just person lacks the knowledge of constructing houses. So, what partnership is Polemarchus referring to?

“Money matters,” Polemarchus says (9).

But once again, Socrates questions this partnership by using the example of buying a horse: “When a horse must be bought or sold with money in partnership; then, I suppose, the expert on horse is a better partner” (9).

Of course, Polemarchus backtracks here and argues that the just person, when dealing with money matters, is useful in depositing money and keeping it safe. Yet, if the money is not being spent, Socrates makes a clever point in arguing that Polemarchus’ definition of justice makes justice “useful for useless things” (10).

Here, Socrates asks: “Isn’t the man who is cleverest at landing a blow in boxing, or any other kind of fight, also the one cleverest at guarding against it?” To which Polemarchus replies, “Certainly” (10). This entails that if one were to attack their opponent effectively, they would know how their opponent defends themselves.

Then Socrates asks a crucial question (which, in my view, stands as a pivotal element in political theory):

So of whatever a man is a clever guardian, he is also a clever thief? (10)

Therefore, the just person “has come to light as a kind of robber … Justice, then, seems … to be a certain art of stealing, for the benefit, to be sure, of friends and the harm of enemies” (10–11).

Regardless of Socrates’ evisceration of Polemarchus’ definition of justice, Polemarchus still contends that “justice is helping friends and harming enemies” (10–11). Yet, what does Polemarchus define as a friends and enemy?

“It’s likely,” Polemarchus says, “ that the men one believes to be good, one lives, while those he considers bad one hates” (11). However, Socrates finds this to be arbitrary as humans make mistakes in whom they consider to be good and bad people. Therefore, if an individual inflicts harm upon someone they perceived as an enemy but who was, in reality, a virtuous person, then, by Polemarchus’ definition, the just individual ends up harming those who they ought to be treating as friends.

For the sake of argument, Polemarchus states that we can redefine our definition of friend and enemy to be those who are actually good and those who are actually bad — not just by one’s belief, but by character. So — do good to friends and harm to enemies.

The dialogue continues between Socrates and Polemarchus:

“Do horses that have been harmed become better or worse?”

“Worse.”

“With respect to the virtue of dogs or to that of horses?”

“With respect to that of horses.”

“And when dogs are harmed, do they become worse with respect to the virtue of dogs and not to that of horses?”

“Necessarily.”

“Should we not assert the same of human beings, my comrade — that when they are harmed, they become worse with respect to human virtue?”

“Most certainly.”

“But isn’t justice human virtue?”

“That’s also necessary.”

“Then, my friend, human beings who have been harmed necessarily become more unjust”

“It seems so.”

(12)

Therefore, the just person is not able to create more injustice in the same vein that musicians are unable to “make men unmusical by music” (12). It is not the work of justice to create injustice.

Ultimately, Socrates concludes: “It is not the work of the just man to harm either a friend or anyone else, Polemarchus, but of his opposite, the unjust man” (13).

d) Socrates and Thrasymachus

Throughout Socrates and Polemarchus’ conversation, “Thrasymachus had many times started out to take over the argument … but he had been restrained by the men sitting near him …” (13). In fact, Thrasymachus “flung himself” at Socrates and Polemarchus “as if to tear [them] into pieces” (13)

Upset with the Socratic method, Thrasymachus tells Socrates:

If you truly want to know what the just is, don’t only ask and gratify your love of honor by refuting whatever someone answers — you know that it is easier to ask than to answer … (13)

Socrates was astounded by Thrasymachus’ harsh words and frightened by the way Thrasymachus’ presence. Socrates responds by telling Thrasymachus that he does not intend to anger Thrasymachus or to make light of the situation — Socrates admits to being concerned about the question of justice.

Thrasymachus continues belittling Socrates as he finds it laughable that Socrates only asks questions and doesn’t give any answers. To this Socrates responds, telling Socrates:

How could a man answer who, in the first place, does not know and does not profess to know; and who, in the second place, even if he does have some supposition about these things, is forbidden to say what he believes by no ordinary man? (15)

After some banter, Thrasymachus finally tells us what the definition of justice is:

The just is nothing other than the advantage of the stronger.

(15; emphasis mine)

Thrasymachus expands upon this definition (again, after some banter) by stating that various cities are ruled in different ways. He states that “some cities are ruled tyrannically, some democratically, and some aristocratically” (16). From here, Thrasymachus makes the argument that, regardless of the type of rule, each city sets up its own laws that it deems as just.

Socrates responds to Thrasymachus’ argument by arguing that rulers make mistakes. He asks Thrasymachus: “When [rulers] put their hands to setting down laws, do they set some down correctly and some incorrectly?” (16); to which Thrasymachus agrees. Because some rulers act incorrectly, going against their interests, then justice must also appear to be the opposite of Thrasymachus’ argument — it is just to do what is disadvantageous for the stronger. Therefore, Socrates says, “the advantage of the stronger would be no more just than the disadvantage” (17).

Thrasymachus understands Socrates’ argument and makes a smart response. He argues that when one occupies the position of a particular trade — like that of a doctor, craftsman, or ruler — they are not making mistakes while occupying this position. For example, if a doctor makes a mistake and hurts a patient, they are not acting as a doctor because a doctor is one who heals people. To this point, rulers — those who are true rulers — will not be making decisions that are disadvantageous for them. “The ruler,” Thrasymachus says, “insofar as he is a ruler, does not make mistakes” (18).

Socrates answers Thrasymachus’ argument by analyzing what a ruler is in the precise sense. Socrates gives an example of the doctor: a doctor cares for the sick. But what is advantageous for the doctor? “Is there then any advantage for each of the arts other than to be as perfect as possible?” Socrates asks (19). The art of medicine “was devised for the purpose of providing what is advantageous for a body” (19). In this manner, “medicine doesn’t consider the advantage of medicine, but of the body” (20).

From here, we are able to see Socrates’ argument play out when extended to the position of a ruler. Socrates states:

There isn’t ever anyone who holds any position of rule, insofar as he is ruler, who considers or commands his own advantage rather than that of what is ruled and of which he himself is the craftsman … (20)

Of course, Thrasymachus becomes flustered by this as his definition of justice is heavily contested. However, Thrasymachus notes that the just person does not necessarily have as much as the unjust person: “the just man everywhere has less than the unjust man” (21). In this case, “the just is the advantage of the stronger, and the unjust is what is profitable and advantageous for oneself” (22).

Thrasymachus’ argument is not persuasive to Socrates: “I am not persuaded; nor do I think injustice is more profitable than justice …” (22). Because Socrates and Thrasymachus agree that the “benefit of each art is peculiar” (like the art of medicine being different than the art of a sailor), the art of a ruler must be distinct from the other types of arts (24). Socrates continues by describing that rulers work for pay — and that they have a personal benefit from ruling. Yet, those who are true rulers — with ruling as their art — are hesitant to rule as they only seek to rule by necessity. Socrates contends that rulership, as an art, must benefit the ruled rather than the rulers. So, justice, for Socrates, is not the advantage of the strong because a true ruler fears to rule: “the greatest of penalties is being ruled by a worse man if one is not willing to rule oneself” (25).

Though Socrates’ contests Thrasymachus’ definition of justice, he finds Thrasymachus’ argument about injustice being more profitable than justice to be concerning. Socrates attempts to dismantle Thrasymachus’ argument that “those who can do injustice perfectly” are good as they “are able to subjugate cities and tribes of men to themselves” (26). Through back and forth questioning, Socrates begins by establishing an analogy between various fields of artistry, like music and medicine. He questions Thrasymachus about whether an individual who is knowledgable in a partiular field is considered wise in that art — to which Thrasymachus agrees. From here, Socrates examines the just man being knowledgeable about all things just and the unjust man being unknowledgable about justice. The just person does not seek to surpass those like them, but only seek to surpass those not like them; like how a doctor does not try to surpass other doctors in the art of medicine, but tries to surpass those who do not know the art of medicine.

Therefore, Socrates states:

The just man is like the wise and good, but the unjust man like the bad and unlearned. (29)

The conversation continues as Thrasymachus is resistant to Socrates. Socrates asks:

Do you believe that either a city, or an army, or pirates, or robbers, or any other tribe which has some common unjust enterprise would be able to accomplish anything, if its members acted unjustly to one another? (30)

Thrasymachus responds, saying, “Surely not” (30). From here, Thrasymachus admits that if a city, or an army, or pirates, or robbers, or any other tribe acted in a just fashion, they would be able to accomplish many things. Therefore, whatever is attempting to be accomplished cannot be accomplished if injustice stands in the way — making injustice the enemy of what one wants to accomplish.

Socrates, then, asks this question: “And the gods, too, my friend, are just?” (31; emphasis mine). To which Thrasymachus replies, “Let it be” (30). My personal opinion on this point is that Thrasymachus should have contested this question.

At any rate, Socrates gets Thrasymachus to admit that there are virtues for each thing assigned: the virtue of the eyes is to see; the virtue of the ears is to hear. Following the lines of vice and virtue, Socrates explains that “a bad soul necessarily rules and manages badly while a good one does all these things well” (33). He comes to this conclusion by conceptualizing blindness as a vice to the eyes and deafness as a vice to the ears.

Thus, “the just soul and the just man will have a good life, and the unjust man a bad one” (33). In this case, injustice is not more profitable than justice.

Conclusion

Book One of Plato’s Republic is pivotal in understanding the foundations of political theory in the Western world. We have noted how Socrates skillfully challenges Thrasymachus’ definition of justice being the advantage of the strong. While dismantling Thrasymachus’ initial stance, Socrates guides the argument to a point where Thrasymachus finds himself agreeing with Socrates. Ironically enough, we must ask ourselves if Thrasymachus’ definition is true — not because Thrasymachus was particularly persuasive, but because Socrates made the stronger argument. Therefore, if Socrates won the argument, because he was stronger in the art of persuasion, then it begs the question: is justice the advantage of the strong?

— —

Citation:

Leave a Reply