Power is the simulacrum of seduction

Originally published in 1977, philosopher Jean Baudrillard wrote Forget Foucault for a specific reason — he believed that the works of Michel Foucault were too essentialist, not properly capturing the reality of power and sex. In fact, Baudrillard argued that Foucault’s writings innately contribute to propagation of the hyperreal. But what does this all mean? The purpose of this blog post is to analyze Forget Foucault and offer a critical commentary of the writing.

**Citation Note: Full citation provided at the end of this post

— Forget Foucault —

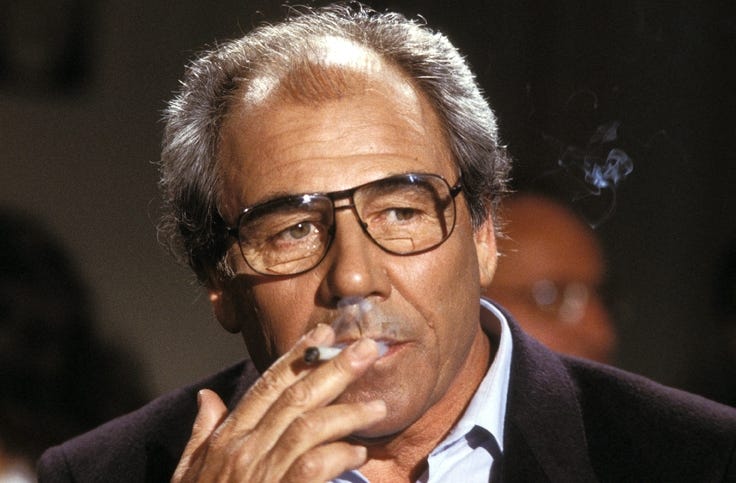

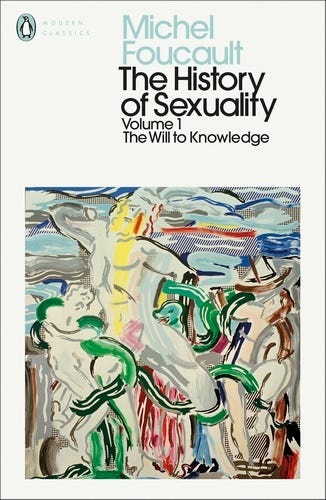

In order to grasp the essence of Forget Foucault, it is essential to acquaint ourselves with the man whom Baudrillard suggests we ought to erase from our memory. Michel Foucault, a French philosopher, dedicated his intellectual pursuits to understanding how bodies are organized within a society and the pervasive influence of discourse on social relations. One of Foucault’s most notable works, Discipline and Punish, published in 1975, delves into the operationalization of power. Additionally, The History of Sexuality Vol. 1, published in 1976, is another one of Foucault’s famous works addressing the historicity and discourse constituting sexuality. Though the subject matter of Foucault’s works is quite complex, both of these books (or really, all of Foucault’s works I’ve read thus far) are recognized for their relative ease of readability.

And most individuals will attest that Foucault’s writing style is excellent, marked by wonderfully transparent clarity — including Baudrillard. In truth, Baudrillard takes issue with Foucault writing too well about power and sex.

Baudrillard begins Forget Foucault by writing:

Foucault’s writing is perfect in that the very movement of the text gives an admirable account of what it proposes … There’s no vacuum here, no phantasm, no backfiring, but a fluid objectivity, a nonlinear, orbital, and flawless writing.

The meaning never exceeds what one says of it; no dizziness, yet it never floats in a text too big for it: no rhetoric either.

(Forget Foucault, 29)

And before you ask, no. Baudrillard is not criticizing Foucault for writing clearly (which is something Baudrillard cannot do). Baudrillard is also not criticizing Foucault for addressing the subject of power; rather, he suggests that Foucault’s transparent and clear writing of power implies that the era of power that Foucault is discussing has already concluded or perhaps never existed in the first place. Baudrillard’s critique lies in the idea that if power can be interpreted, theorized, and examined, then it may no longer be actively operational. Thus, Foucault’s analysis does not go far enough.

Baudrillard continues:

[Foucault’s writings’] strengths and its seduction are in the analysis which unwinds the subtle meanderings of its object, describing it with a tactile and tactical exactness, where seduction feeds analytical force and where language itself gives birth to the operation of new powers.

Such also is the operation of myth, right down to the symbolic effectiveness described by Levi Strauss.

(Forget Foucault, 30)

Here, Baudrillard is describing that Foucault’s analysis of power as an object of study ‘gives birth to the operation of new powers’ by allowing power to differentiate itself from an object of study. He even alludes to calling Foucault’s analysis of power as a myth, with its various symbols and representations. Baudrillard continues:

If Foucault spoke so well of power to us — and let us not forget it, in real objective terms which cover manifold diffractions but nonetheless do not question the objective point of view one has about them, and of power which is pulverized but whose reality principle is nonetheless not questioned — only because power is dead?

Not merely impossible to locate because of dissemination, but dissolved purely and simply in a manner that still escapes us, dissolved by reversal, cancellation, or made hyperreal through simulation (who knows?).

(Forget Foucault, 31)

Again, if power operates as a fluid simulacrum, it must have escaped us in the sense that we would not be able to write about it. Now that we have established a stable foundation for Baudrillard’s criticism, we can adequately say that treating power and sex as objects of study fails to accurately account for what power and sex actually are.

Furthermore, Baudrillard continues:

And what if Foucault spoke to us so well of sexuality (at last an analytical discourse on sex — or a discourse freed from the pathos of sex — that has the textual clarity of discourses which precede the discovery of the unconscious and which do not need the “blackmail of the deep” to say what they have to say), what if he spoke so well of sexuality only because its form, this great production (that too) of our culture, was, like that of power, in the process of disappearing? (Forget Foucault, 31–32)

Similar to his analysis of power, Foucault analyzes sexuality as a subject of study, articulating his thoughts on sexuality with clarity. This is because, akin to power, sexuality was already undergoing a “process of disappearing,” rendering it more accessible for identification and discussion. To clarify, “sex, like man, or like the category of the social, may only last for a while” (Forget Foucault, 32). When discussing the mortality of concepts like power or sex, Baudrillard is arguing that grand theorizations of these complex concepts water down (and do not fully grasp) these concepts. Baudrillard gives two examples of how theorizations of this kind reify the structures that they are criticizing.

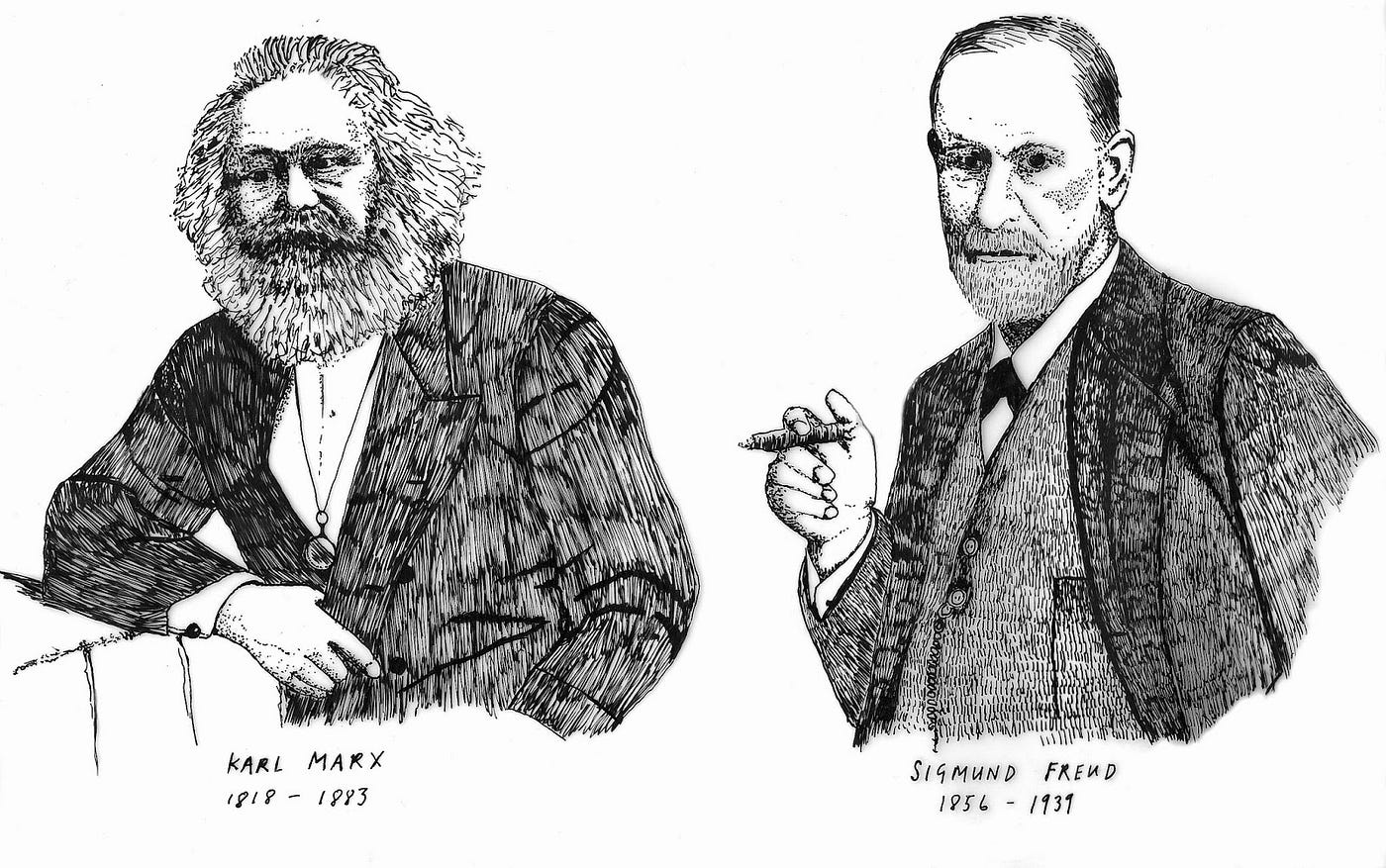

- Firstly, there is psychoanalysis — “In a certain way, psychoanalysis puts an end to the unconscious and desire …”

- Secondly, there is Marxism — “Marxism put an end to the class struggle …”

Why did psychoanalysis and Marxism do these things? “Because it hypostatizes them and buries them in their theoretical project.” (Forget Foucault, 32). (The unconscious is under the guise of psychoanalysis while the class struggle is under the guise of Marx).

Psychoanalytic theory endeavors to comprehend the unconscious by treating it as a tangible reality, almost akin to a physical object; they treat the unconscious as something to be studied and understood. Psychoanalysts aspire to ‘know’ an individual’s drives and craft guidelines for which drives are appropriate and which ones are not. However, this rather reductive project only imitates or mimics the real unconscious, concealing the real unconscious beneath signs and significations, disconnecting the unconscious from the real, and establishing a simulated unconscious divorced from the real. A parallel process unfolds in Marxism, where intricate discussions about class struggle are methodically consolidated under the umbrella term of Marxism. Class struggle is understood in a unitary manner, all consolidated within the volumes of Das Kapital. For Baudrillard, Foucault is engaging in the exact same type of projects, but using the term ‘Foucauldian’ to paper over power and sex:

We have at this point reached the metalanguage of desire in a discourse on sex that has outreached itself by redoubling the signs of sex so as to mask an indeterminacy and a profound disinvestment-the dominant catchword sexual is now equivalent to an inert sexual milieu.

(Forget Foucault, 32)

It is important to emphasize that Baudrillard is not asserting that Foucault is entirely mistaken in his examination of power and sex. Rather, Baudrillard suggests that Foucault’s analysis falls short in capturing the dynamic and ever-changing nature of these concepts because there is a proliferation of signs that seek to define or ‘know’ power and sex:

If, as Foucault states, the bourgeoisie used sex and sexuality to give itself a glorious body and a prestigious truth in order to pass this on then to the rest of society under the guise of truth and banal destiny, it could just be that this simulacrum slips out of its skin and departs with it.

Because he remains within the classic formula of sex, Foucault cannot trace this new spiral of sexual simulation in which sex finds a second existence and takes on the fascination of a lost frame of reference …

(Forget Foucault, 33)

In this quote, Baudrillard is acknoweldging how the bourgeoisie has historically utilized sex and sexuality to reinforce it social standing. However, his critique argues that Foucault’s analysis remains confined with this established framework of traditional concepts, incapable of tracing the shifting intricacies of sex characterized by the proliferation of symbolic representations.

At any rate, Baudrillard finds Foucault to adequately explain how sex and sexuality is policed during his writing:

Discourse is discourse, but the operations, strategies, and schemes played out there are real: the hysterical woman, the perverse adult, the masturbating child, the oedipal family. These real, historical devices, machines that have never been tampered with — no more so than the “desiring machines” in their order of libidinal energy — all exist, and the truth is: they have been true. (Forget Foucault, 33)**

- *Sidenote: the discussion of “desiring-machines” seems to be a reference to Deleuze and Guattari which is interesting because Foucault does not directly comment on desiring-machines.

Undisputedly, strict categorizations of sex and sexuality are produced in a given society, but Foucault fails to examine the fluidity and ever-changing nature of this production and how this production is embedded within a larger economy of signs.

Foucault cannot tell us anything about the simulating machines that double each one of these “original” machines, about the great simulating mechanism which winds all these devices into a wider spiral, because Foucault’s gaze is fixed upon the classic “semiurgy” of power and sex.”

(Forget Foucault, 33)

Although this criticism of Foucault seems minute or as purely a question of semantics, it is integral to note that Baudrillard is concerned with “the frenzies semiurgy* that has taken hold of the simulacrum” (Forget Foucault, 33).

*Semiurgy: The production of new meanings by the creation of new signs

Here, Baudrillard cites Roland Barthes:

“[In Japan], sexuality is in sex and nowhere else. In the United States, sexuality is every where except in sex” (Forget Foucault, 33–34)

But then, Baudrillard asks:

“What if sex itself is no longer in sex?” (Forget Foucault, 34)

This question is extremely important in his criticism of Foucault; when Foucault details a history of sexuality, describing the importance of movements, gestures, peoples, and sexual acts, he confines these terms dominant signs that constitute sex and sexuality at a given time; yet, Baudrillard makes abundantly clear that sex and sexuality have surpassed the traditional categorizations that Foucault analyzed. Baudrillard writes:

“We are no doubt witnessing, with sexual liberation, pornography, etc., the agony of sexual reason.

And Foucault will only have given us the key to it when it no longer means anything.”

(Forget Foucault, 34)

This passage implies that contemporary shifts in societal attitudes, practices, and representations of sex and sexuality have shifted sex and sexuality beyond the confines of physical sexual acts. In a similar vein, though a bit different, Baudrillard extends his criticism of Foucault’s views of sex to his views of power in Discipline and Punish, finding Foucault’s theories to be obsolete.

The Repressive Hypothesis

In The History of Sexuality Vol. 1, Foucault disputes the repressive hypothesis — a commonly held notion that historically, societies have repressed or repressed sexuality by making it hidden; the idea that there has been a systemic effort by authorities, institutions, and cultural norms to regulate sex and sexuality. Foucault’s gripe with the repressive hypothesis is that sexuality was never repressed, but was instead, always topical and readily present in various formations of discourse. To put simply, no one talks about sex, yet sex is all we talk about. Sex and sexuality are generally understood as something repressed, but the reality is that sex and sexuality are always displayed — in various formations.

Baudrillard agrees with Foucault on the basis that the repressive hypothesis is too simplistic, as it attempts to view sex as unidirectional — a top-down struture whereby the the privileged classes exert their sexual repression upon the lower classes. However, this is erroneous:

On this basis, it is too easy to say that the proletariat should have been the first class affected by repression, while history shows that the privileged classes first experienced it. In conclusion, the hypothesis concerning repression doesn’t hold up. (Forget Foucault, 36)

Baudrillard is not innately concerned with the repressive hypothesis, but there is another hypothesis he finds intriguing: “the hypothesis concerning a repression that originates from much farther away than the horizon of manufacturing and that simultaneously includes the whole horizon of sexuality” (Forget Foucault, 36). This argument is a bit nuanced and concern’s the body’s relationship to sex and sexuality. Although Foucault disputes the repressive hypothesis, he still finds power operationalizing upon the body. This is extremely evident throughout his History of Sexuality where he identifies particular markers that designate sex and sexuality upon the body. However, Baudrillard does not find the body to be the object whereby power or repression finds itself upon. Instead, Baudrillard finds that repression operates through sex.

One might as well say that repression in the maximal hypothesis, is never repression OF sex for the benefits of who knows what, but repression THROUGH sex (a grid of discourses, bodies, energies, and institutions imposed through sex, in the name of “the talking sex”).

And sex which has been repressed only hides that repression by means of sex.

(Forget Foucault, 36)

In other words, Baudrillard is positing a complex understanding of sexuality where repression is intricately woven into the very fabric that constitutes sexuality rather than sexuality being a victim of repressive systems. Sexuality where repression is intricately woven into the fabric that constitutes sexuality involves a broader range of elements, such as discourses, bodies, energies, and institutions imposed through symbolic representations. Baudrillard suggests that the repression itself is hidden within the very acts and discussions about sex — not just something to be widely analyzed by philosophers.

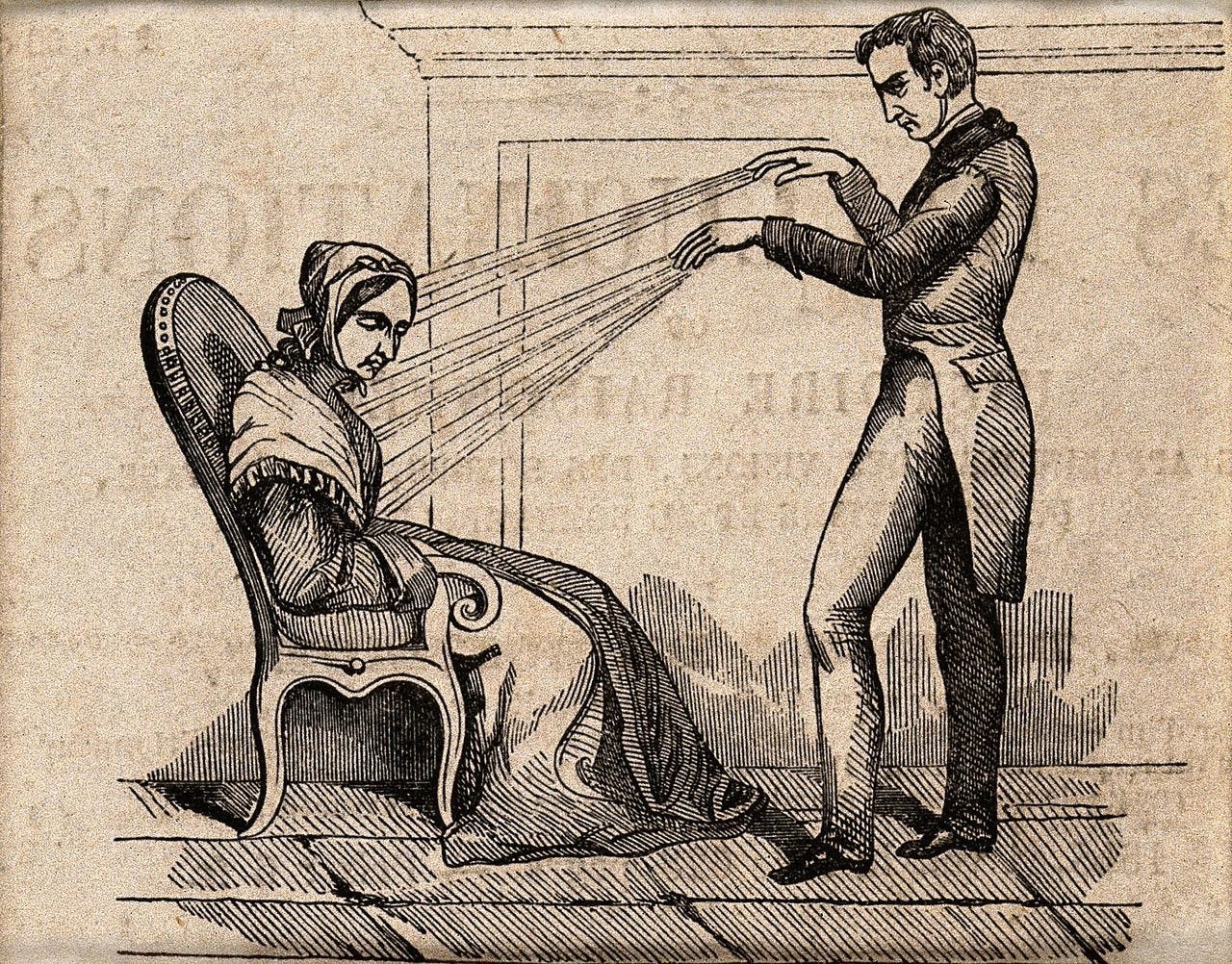

Production vs. Seduction // Pornography

Baudrillard continues to discuss the difference between production and seduction.

The original sense of “production” is not in fact that of material manufacture; rather, it means to render visible, to cause to appear and be made to appear: pro-ducere.** (Forget Foucault, 37)

**Pro-ducere in Latin: “present active infinitive of prōdūcō (“I lead or bring forth”)”

In this manner, sex and sexuality are produced in the sense of being made visible. “Sex is produced as one produces a document, or as an actor is said to appear (seproduire) on stage. To produce is to force what belongs to another order (that of secrecy and seduction) to materialize” (Forget Foucault, 37). Therefore, sex is not created, but rather brought to light (produced). On the other hand, seduction is opposed to production:

Seduction withdraws something from the visible order and so runs counter to production, whose project is to set every thing up in clear view, whether it be an object, a number, or a concept. (Forget Foucault, 37)

Society writ large attempts to make things visible, to constantly produce sex. “Let everything be produced, be read, become real, visible, and marked with the sign of effectiveness … This is how sex appears in pornography, but this is more generally the project of our whole culture, whose natural condition is ‘obscenity’” (Forget Foucault, 37). And so, Foucault’s analysis is one that analyzes discourse(s) shaping reality, yet this discourse is always visible. This ensnares Foucauldian thought, as Foucault conflates production with seduction. This confusion arises from Foucault’s focus on the visible, leading to the misconception that acts he perceives as repressed are inherently seductive. To this point, Baudrillard writes: “Ours is a culture of ‘monstration’ and demonstration, of ‘productive’ monstrosity (the ‘confession’ so well analyzed by Foucault is one of its forms)” (Forget Foucault, 37).

We never find any seduction there — nor in pornography with its immediate production of sexual acts in a frenzied activation of pleasure; we find no seduction in those bodies penetrated by a gaze literally absorbed by the suction of the transparent void.

Not a shadow of seduction can be detected in the universe of production, ruled by the transparency principle governing all forces in the order of visible and calculable phenomena: objects, machines, sexual acts, or gross national product.

(Forget Foucault, 38)

Pornography is not seductive. It is the production of sexual acts, divorced from sex itself. Baudrillard writes that “pornography is only the paradoxical limit of the sexual … a mad obsession with the real” (Forget Foucault, 38). Pornography itself is hyper-visible, attempting to offer instantaneous pleasure, while desperately trying to mimic and package itself as the real — ultimately believing itself to be the real. Pornography is forever searching for the presentation of itself as true seduction, yet remains a force of production.

In western society, “we do not understand … those cultures for which the sexual act has no finality in itself and for which sexuality does not have the deadly seriousness of an energy to be freed, a forced ejaculation, a production at all cost, or of a hygienic reckoning of the body” (Forget Foucault, 38–39). This analysis properly explains the increased amounts of pornography addictions in the west and the overall culture surrounding sex (such as the obsession with body counts, the marketability of a partner, performance anxiety, the perpetuation of unrealistic sexual standards, infidelity, and so on). It should come as no surprise that the west markets sex as a commodity, a “forced ejaculation” whereby sex is viewed as part in parcel with experience culture, embedded within an economy of signs. Yet, whatever happened to love?

Unlike the west, there are cultures …

… which maintain long processes of seduction and sensuousness in which sexuality is one service among others, a long procedure of gifts and counter-gifts; lovemaking is only the eventual outcome of this reciprocity measured to the rhythm of an ineluctable ritual. (Forget Foucault, 39)

Unfortunately, “for us, this no longer has any meaning: for us, the sexual has become strictly the actualization of a desire in a moment of pleasure — all the rest is ‘literature’” (Forget Foucault, 39). For Baudrillard, the sex and sexuality that Foucault is analyzing are rooted in production (to make visible), where sex and sexuality are deemed as a commodity — a commodity that defines one’s subjectivity. He writes:

Ours is a culture of premature ejaculation. More and more, all seduction, all manner of seduction (which is itself a highly ritualized process), disappears behind the naturalized sexual imperative calling for the immediate realization of a desire. Our center of gravity has in fact shifted toward an unconscious and libidinal economy which only leaves room for the total naturalization of a desire bound either to fateful drives or to pure and simple mechanical operation, but above all to the imaginary order of repression and liberation. (Forget Foucault, 39)

The mechanical operationalization of desire that Baudrillard is referring to consists of everything being made transparent whereby individual moments and experiences — no matter how intimate — are rooted in forces of production. The forces of sex and sexuality are akin to the flow of capital . Baudrillard highlights this point:

Nowadays, one no longer says: “You’ve got a soul and you must save it,” but: “You’ve got a sexual nature, and you must find out how to use it well.”

“You’ve got an unconscious, and you must learn how to liberate it.”

“You’ve got a body, and you must know how to enjoy it.”

“You’ve got a libido, and you must know how to spend it,” etc., etc.

This compulsion toward liquidity, flow, and an accelerated circulation of what is psychic, sexual, or pertaining to the body is the exact replica of the force which rules market value: capital must circulate …

(Forget Foucault, 39-40)

In the vein of Deleuze and Guattari (whom I know Baudrillard criticizes here), the body is very much a machine. And this machine, through various symbolic representations, is gridded upon and by a social body that seeks to maximize its efficiency. One cannot be solely be sexual — they must be productive with their sexuality.

A few things come to mind for me here:

The production of the body seems to place individuals in a position where they see themselves as vessels constantly bound to productivity, encompassing both work-labor and sexual-labor. In terms of liberating this body, there seem to be three points that I’ve gathered/thought of while reading this part.

Firstly, liberation relies on previous repression, so it is rooted in it (this was stated above.

Secondly, liberation requires a higher power to tell you that you are free. So, can one really call themselves free if they are told that they are free?

Thirdly, most evident here, capitalism has infiltratated — or rather has become constitutive with the body — meaning that liberation of the body reinscribes viewing the body as private property capable of selling its labor.

Repression vs. Liberation // Liberation is Repression

At this point, the ultimate question lies in how one is able to escape these forces of production (if at all). Is everything fundamentally made visible? Is there an escape plan?

Foucault tells us: “nothing functions with repression (repression), everything functions with production; nothing functions with repression (refoulement), everything functions with liberation” (Forget Foucault, 40–41). Ironically enough, Baudrillard finds repression and liberation to be one and the same — “it is the same thing.”

However, this sort of liberation is not just found within sexual revolutions. Even within psychoanalysis and Marxism we find practices of liberation to be synonymous with repression. Whether one is invested in psychoanalysis or Marxism (or tries to do away with them), notions of liberation are repressive:

Historically, this process has been building up for at least two centuries, but today it is in full bloom with the blessing of psychoanalysis — just as political economy and production have only made great strides with Marx’s sanction and blessing.

It is this conjecture which dominates us completely today, even through the “radical” contestation of Marx and psychoanalysis.

(Forget Foucault, 41)

At any rate, the category of the sexual and sexual discourse were not always present. This is similar to how “the category of the clinical and clinical gaze came into being” (Forget Foucault, 42). Prior to the categories of the sexual and the clinical, there was nothing before—there was no genuine sexuality because there was no need for one. And yet, so-called ‘modern societies’ demonized earlier societies for not being liberated — from the west’s perspective, these societies were the ones that were repressed. From here, psychoanalysis justified the erasure of non-normative ‘truths’ surrounding sex and sexuality, proliferating an overarching hierarchy for how sexual drives operate. Baudrillard rightfully says: “How incredible is the racism of truth, the evangelical racism of psychoanalysis” (Forget Foucault, 42). It is with heavy irony that the question of repression remains unsettled for the west, particularly because the west crafted the category of the sexual:

It is nonetheless without ambiguity for the others: they know neither repression nor the unconscious because they do not know the category of the sexual.

We act as if the sexual were “repressed” wherever it does not appear in its own right: this is our way of saving sex through the “sex principle.”

(Forget Foucault, 42–43)

Therefore, it is extremely easy for one to argue that whatever does not appear is repressed (i.e., the absence of something serves as the regulation of sex and sexuality). However, this logic presumes that sex and sexuality are rooted in production rather than seduction. It is with heavy irony that the west viewed earlier societies as uncivilized (and repressive) for not regulating and concealing sex, yet the west consistently produces the clinical gaze, regulating sexuality. This is not to imply that earlier societies lacked an awareness of sexuality but it’s also not to assert that tey possessed a structured framework or grammar for it either. Baudrillard is only arguing that the west’s view of sexuality ought not be applied to other cultures who have different perspectives regarding sex and sexuality.

At this point, you might be wondering how these arguments criticize Foucault. Here’s why: Foucault is utilizing the terms of sex, sexuality, and the clinical gaze in order to analyze social relations and the organization of bodies. Therefore, he is utilizing a western, universalist notion of sex and sexuality to describe the way in which the discourse operates. To put simply, Baudrillard challenges the very notion of sexuality as a fixed and inherent reality. If sexuality does not exist, which it does not, than it cannot be repressed. It can only be simulated.

And on that basis, then, it becomes possible again to say with Foucault: there is not and there has never been any repression in our culture either — not, however, according to his meaning, but in the sense that there has never truly been any sexuality.

Sexuality, like political economy, is only montage (all of whose twists and turns Foucault analyzes); sexuality as we hear about it and as it “is spoken,” even as the “id speaks,” is only a simulacrum which experience has forever crossed up, baffled, and surpassed, as in any system.

The coherence and transparence of homo sexualis has never had more reality than that of homo economicus.

(Forget Foucault, 43; emphasis mine)

This passage encapsulates Baudrillard’s critique effectively. The framework of sex and sexuality, as explored by Foucault, serves as an object of study where sex and sexuality mimic the real. However, for Baudrillard, sex and sexuality are a manufactured, fabricated, and simulated reality. Baudrillard draws an analogy with a film montage, where fragments of film come together to form the complete movie. This comparison underscores his argument that sex and sexuality, like economic identities, are constructed simulated realities from various fragments —with these fragments being what elements of power and sex which Foucault views as an object of study and finds to be the real. Just as capitalism simulates reality and presents itself as genuine, sex and sexuality are similarly simulated, a point Baudrillard critiques Foucault for not addressing explicitly.

Speech and Repression // Criticism of the Molecular

In this section, Baudrillard explains that it is useless to argue over the order of speech and repression. Either a) speech comes first and repression second or b) repression comes first and speech second. Regardless, “both hypotheses don’t change much of anything” (Forget Foucault, 44). Yet, he must have taken issue with the first hypothesis because Baudrillard this is the one that Foucault aligns with.

Ultimately, Baudrillard is skeptical of the traditional idea that power fundamentally relies on repression. Though Baudrillard does question why an imaginary concept like repression is needed for power. So, if speech came first, there is no overarching explanation as to why repression would follow if power relies on discourse. Instead, “one sees better why speech (a metastable system) would come after repression, which is only an unstable power system” (Forget Foucault, 44).

Regardless of which hypothesis is correct, Baudrillard is questioning Foucault’s notion that sex and sexuality only exists within discourse. He posits a few questions (Forget Foucault, 45):

- If sex exists solely when it is spoken and discoursed about and when it is confessed, what was there before we spoke about it?

- What break establishes this discourse on sex, and in relationship to what?

- We see what new powers are organized around it, but what peripeteia of power instigates it?

- What does it neutralize, or settle, or put to an end* (otherwise who can ever pretend to end it, as Foucault states on p. 157, “to break away from the agency of sex”)?

Giving meaning to sex “is not an innocent undertaking” as power constitutes the terms that define sex. Baudrillard is pointing out that the act of giving meaning to sex involves a exercise of power, but in the process, the actual essence of sex becomes divorced or detached from this meaning. As a result, power, in its attempt to attribute meaning to sex, becomes a simulacrum of seduction — an imitation without a true referent.

It is only from this point on that we can conceive of a new peripeteia of power-a catastrophic one this time-where power no longer succeeds in producing the real, in reproducing itself as real, or in opening new spaces to the reality principle, and where it falls into the hyperreal and vanishes: this is the end of power, the end of the strategy of the real.

(Forget Foucault, 45)

Yet for Foucault, the question of power collapsing — the peripeteia of power — does not come up. Foucault views power at the level of the micro- which Baudrillard is wary of:

Foucault, power operates right away like Monod’s genetic code, according to a diagram of dispersion and command (DNA), and according to a teleonomical order … the kind of generative inscription of the code that one expects-an immanent, ineluctable, and always positive inscription that yields only to infinitesimal mutations. (Forget Foucault 46)

Here, Baudrillard says, “it is precisely this collusion that we must denounce, or laugh about” (Forget Foucault, 46).

**Though, I must admit that finding a warrant to back Baudrillard’s assertion here is quite difficult. I guess the most I can make of Baudrillard’s argument is to be careful tying scientific theories to social theories. Why a microphysics of power or molecular understanding of desire is problematic, I do not know. Regardless, I feel that Baudrillard’s argument is quite reductive nonetheless.

Madness and Civilization— An Honorable Mention

This was a quick blurb by Baudrillard, but I figured I might as well include it

Baudrillard questions why sex did not go through a confinement phase like that of madness. This question is particularly important within Foucault’s repertoire as Foucault published Madness and Civilization in 1961.

Why wouldn’t sex, like madness, have gone through a confinement phase in which the terms of certain forms of reason and a dominant moral system were fomented before sex and madness, according to the logic of exclusion, once more became discourses of reference?

Sex once more becomes the catchword of a new moral system; madness becomes the paradoxical form of reason for a society too long haunted by its absence and dedicated this time to its (normalized) cult under the sign of its own liberation.

(Forget Foucault, 47)

Evidently, both sex and madness were pushed to the back burner with dialogue surrounding these topics being scarce. However, madness was met with confinement through the creation of psychiatric institutions and asylums — with individuals deemed as abnormal being met with extreme punishment. Baudrillard is asking why madness was met with confinement while sex was not met with the same intensity.

Power as the Simulacrum of Seduction

To Foucault’s credit, Baudrillard does argue that Foucault exposes the illusions of attributing power to a substance of production or desire and emphasizes that power does not have its roots in ordinary production relations but rather models them. Baudrillard writes:

One form dominates and is diffracted into the models characteristic of the prison, the military, the asylum, and disciplinary action.

This form is no longer rooted in ordinary relations of production (these, on the contrary are modeled after it); this form seems to find its procedural system within itself and this represents enormous progress over the illusion of establishing power in a substance of production or of desire.

(Forget Foucault, 50)

For Baudrillard, Foucault exposes the illusions of attributing power to a substance of production or desire and emphasizes that power doesn’t have its roots in ordinary production relations but rather models them. However, Baudrillard argues that Foucault stops short of revealing the simulacrum of power itself. Most importantly: “Foucault unmasks all the final or causal illusions concerning power, but he does not tell us anything concerning the simulacrum of power itself” (Forget Foucault, 50). Despite Foucault’s insights into dispelling certain illusions about power, there remains a dimension of power that is not fully explored — the aspect of power as a simulacrum, a representation that may not have a direct correlation with reality.

Baudrillard writes about Foucault’s view of power:

Neither central, nor unilateral, nor dominant, power is distributional; like a vector, it operates through relays and transmissions. Because it is an immanent, unlimited field of forces, we still do not understand what power runs into and against what it stumbles since it is expansion, pure magnetization. (Forget Foucault, 52)

However, Baudrillard raises a crucial question here. If power were an infinite magnetic infiltration of the social field, why hasn’t it overcome all resistance? Though this is a rhetorical question, Baudrillard’s question highlights the paradoxical nature of Foucault’s conceptualization of power. If power is so infinite, pervasive, and all-encompassing, then it should have subjugated everything in its path. Yet, resistance still occurs. Conversely, if power were merely a one-sided act of submission, why hasn’t it been overthrown everywhere under the pressure of antagonistic forces.

Baudrillard argues that this apparent contradiction poses a problem for “materialist” thinkers:

For “materialist” thinking, this can only appear to be an internally insoluble prob lem: why don’t “dominated” masses immediately overthrow power?

Why fascism?

Against this unilateral theory (but we under stand why it survives, particularly among “revolutionaries” — they would really like power for themselves) …

(Forget Foucault, 52)

So … what is power for Baudrillard?

“We must say that power is something that is exchanged” (Forget Foucault, 52).

Though, Baudrillard is not talking about power being exchanged in an economical sense, “but in the sense that power is executed according to a reversible cycle of seduction” (Forget Foucault, 52).

In this “reversible cycle of seduction”, power seeks its own death. We must remember that seduction is that which is not transparent. Thus, power attempts to make itself appear unilateral or segmentary (“this is the dream of power imposed on us by reason”), “but nothing yearns to be that way; everything seeks its own death, including power” (Forget Foucault, 53). In this sense, power being exchanged is the equivalent of seeking its own death — it becomes abolished through the exchange. This reversal or exchange makes power the simulacrum of seduction as power lacks transparency by dying through its exchange.

However, we ought not assume that seduction and power are the same:

Seduction is stronger than power because it is a reversible and mortal process, while power wants to be irreversible like value, as well as cumulative and immortal like value. (Forget Foucault, 53)

This is the difference: power seeks to be irreversible and immortal while seduction doesn’t. Power seeks to belong to the order of the real while seduction “does not partake of the real order” (Forget Foucault, 53).

In pages 54–55, Baudrillard describes the real as “a stockpile of lifeless matter, bodies, and language.” From what I’ve gathered, his argument is that the real may not appear intriguing or interesting which is what makes elements of production (like that of power, sex, or economy) seem fascinating. The possibility of these elements collapsing — “the economy is going to crash!” — is what gives individuals meaning. Yet, Baudrillard attempts to contrast the real as a question of production with the real as a question of seduction. Obviously, we cannot say that production and seduction are the real, but Baudrillard is suggesting a paradigm shift. With power, sex, and economy being a simulacrum of seduction, Baudrillard seems to be arguing that we should lean on the side of seduction rather than production.*

*I could be wrong on this last part and am open to general criticism.

You Say You Want a Revolution

Now, the question is: what next? Revolution? What might revolutions look like in a Baudrillardian sense?

Baudrillard answers:

The revolution has already taken place.

Neither the bourgeois revolution nor the communist revolution: just the revolution.

(Forget Foucault, 58)

In the end, endeavors to deconstruct the mechanisms of power or sexuality transform into symbols that reintegrate into a symbolic economy. Baudrillard explores forms of resistance and shows how (some) power formations camouflage themselves through “force relations such as dominator/dominated and exploiter/exploited” (Forget Foucault, 60). However, this strategy “funnels resistance into frontal confrontations” (which Baudrillard applies to guerrilla warfare within Foucault’s framework); these strategies “replace classical battle scenarios” (Forget Foucault, 60).

To put simply:

For in terms of force relations, power always wins, even if it changes hands as revolutions come and go. (Forget Foucault, 60)

Power consistently prevails in terms of force relations, even if it undergoes transformations during revolutions.

Individuals inherently perceive power as a personal confrontation, a challenge that extends to the point of death. The response to this challenge is not framed as a direct opposing force but rather as a counterchallenge. Throughout history, this counterchallenge, with its immeasurable potency, urges those in power to either push it to its limits or to counter with a form of power that is comprehensive, irreversible, unscrupulous, and boundless in its use of violence:

A challenge to power to be power, power of the sort that is total, irreversible, without scruple, and with no limit to its violence.

No form of power dares go that far (to the point where in any case it too would be destroyed).

And so it is in facing this unanswerable challenge that power starts to break up.

(Forget Foucault, 60–61)

Many have tried and failed in the fight against power:

Against that “strategy” which is not a strategy, power has defended itself in every possible way (this is exactly what constitutes its practice): by being democratized, liberalized, vulgarized, and, more recently, decentralized and deterritorialized, etc. (Forget Foucault, 61)

Although Foucault has offered a dramatic shift in how to discuss power, Baudrillard writes that “the turnaround Foucault manages from power’s repressive centrality to its shifting positivity is only a peripeteia” (Forget Foucault, 63). Foucault only marked a sudden shift in how to view power, but we still remain within the realm of political discourse. Instead, as Baudrillard emphasizes, we must go beyond political discourse and engage in a form of symbolic violence.

Power is Dead!

Baudrillard says it best:

WHEN ONE TALKS SO MUCH about power, it’s because it can no longer be found anywhere.

The same goes for God: the stage in which he was everywhere came just before the one in which he was dead. Even the death of God no doubt came before the stage in which he was everywhere.

The same goes for power, and if one speaks about it so much and so well, that’s because it is deceased, a ghost, a puppet; such is also the meaning of Kafka’s words: the Messiah of the day after is only a God resuscitated from among the dead, a zombie.

(Forget Foucault, 64)

Foucault speaks so well of power that it must mean it has long been deceased. This detailed analysis of power is a “nostalgia effect” indicating a longing for the past when power was easily digestible. The power that Foucault analyzes can be equated to the sex found in pornography — divorced from the real, yet claiming to represent the real: a true simulacrum of seduction.

—

“Power did not always consider itself as power, and the secret of the great politicians was to know that power does not exist.” — Jean Baudrillard

—

— —

Citation:

- Baudrillard, Jean. Forget Foucault. Published by Semiotext(e). 1977.

Leave a Reply