Introducing a Deleuzoguattarian philosophy in the classroom through a series of becomings

For those that don’t know, I teach competitive speech and debate. No, I don’t teach the type of debate you see amongst politicians on the big screen — we’re a bit more polished. As many aren’t aware of specific debate formats, it is important to know that philosophy plays a large role in our debates. This should be decently obvious: the way we debate about public policy is guided by philosophy. When we say liberal and conservative, aren’t we referring to a set of belief-systems? What impacts should we prioritize? The climate? The economy? Autonomy? Safety? Our criminal justice system has the word “justice” in it, so… what is justice?

Due to some misconceptions about various philosophies, I decided to give my students a history of philosophy lecture. In this blog post, I will explain a history of philosophy and show/analyze homework assignments my middle and high school students turned in.

Their homework assignment went as followed:

Make a PowerPoint presentation about a superhero/villain (in popular culture) that personifies a philosophy we discussed in class.

I hope you enjoy their creativity as much as I do!

The Ancient Greeks (480–323 B.C.)

Socrates: a smelly old man who always asked questions. His famous quote is: “I know that I know nothing.” He constantly questioned passersby about the meanings of various virtues and ideas. Socrates was concerned with questions of justice, happiness, life, etc. Because of his philosophical nature, he was sentenced to death for ‘corrupting the youth’ (although he never gave any answers — he just asked questions). It makes one think: Why might a (corrupt) government not want people to ask questions?

Here’s my homework assignment (for reference):

Plato: a student under Socrates. Plato wrote the Republic which is one of the most profound texts in political philosophy. In Plato’s Republic, Plato writes from the point of view of Socrates. To understand Plato’s Republic, I find it necessary to break the book up into three main parts:

- The Ideal City. Socrates describes his ideal city (or is it Plato’s ideal city?) as being one that lies to its citizens. Why lie to citizens? So citizens know to keep to themselves and do their jobs. In fact, keeping to oneself and doing one’s job is Socrates’ definition of justice. Is he telling this to philosophers? Or is he telling this to those easily manipulable? If a philosopher-king can convince a population to listen to them, wouldn’t that be the perfect world?

- The Theory of Forms. Plato’s theory of forms suggests that Plato is a natural law thinker. This means that he believes morality is innately embedded within the universe. For Plato, there is a true form to everything. For example, when we say “justice”, we aren’t necessarily talking about the true form of justice. The goal of the philosopher is to uncover what these forms actually are.

- The Allegory of the Cave. This is essential to understanding how Plato conceptualizes politics. Prisoners are chained facing the wall of a cave with the shadows on the wall constituting their reality. When one of the prisoners leaves the cave, they recognize that the reality the prisoners believe is not the truth — the truth has been fabricated. For Plato, this allegory is representative of politics. We’ve all seen it — constituents are lied to and the reality we’re used to is constructed.

Aristotle: a student under Plato. Aristotle disagrees with the theory of forms. Why look for morality out there when we have a physical reality right here? Surely, Aristotle believes we ought to be virtuous, but we’ll definitely miss the mark. My professor used a brilliant example here: whiskey (although as a fan of Dionysus, I would probably use wine). (And before you ask, no, I did not use this example with middle schoolers). In ancient Greece, you never turned down wine at parties — never. If you didn’t want to drink, you would be given a single drop. And if you wanted to drink a lot, you could drink as much as your heart desired. As each and every person has a different tolerance level, each person needs to find where their limit is to peacefully coexist: we don’t want our uncles to be fighting in the middle of a Denny’s on Cinco de Mayo because they drank too much. This example is important because it shows us the notion of limit: we strive to be virtuous, but we need to find where our limits are. Sure, you might drink too much — but try not to do it again. It’s okay to miss the mark, but work to be as virtuous as possible.

Ultimately, we all approach the world differently and have different limits, so Aristotle solely finds ethics to be necessary when dealing with other people. When you’re by yourself do you need ethics? Aristotle doesn’t think so.

The Enlightenment Period (1685–1815)

**Machiavelli is not from the Enlightenment period but understanding his work is important to understand Hobbes (who writes right before the Enlightenment period)**

Niccolo Machiavelli (early 1500’s): an Italian philosopher. Although Machiavelli doesn’t classify as an Enlightenment thinker, I feel that it is important to discuss his place in philosophy (especially when we get to Hobbes). Known as evil, Machiavelli wrote The Prince as an attempt to teach Lorenzo di Piero de’ Medici, ruler of Florence, how to successfully rule Italy. Machiavelli believed that violence must be used strategically by rulers. If a prince kills everyone for no real reason, the people will overthrow the prince. By the same logic, if a prince doesn’t punish people at all, people would have no incentive to follow the law and would overthrow the prince. However, Machiavelli recognizes that the people must fear the leader. He recommends that the ruler commit brutal acts of violence to deter others from challenging their authority. The peoples’ relationship with the prince must be a love/fear relationship — this type of relationship is best for control.

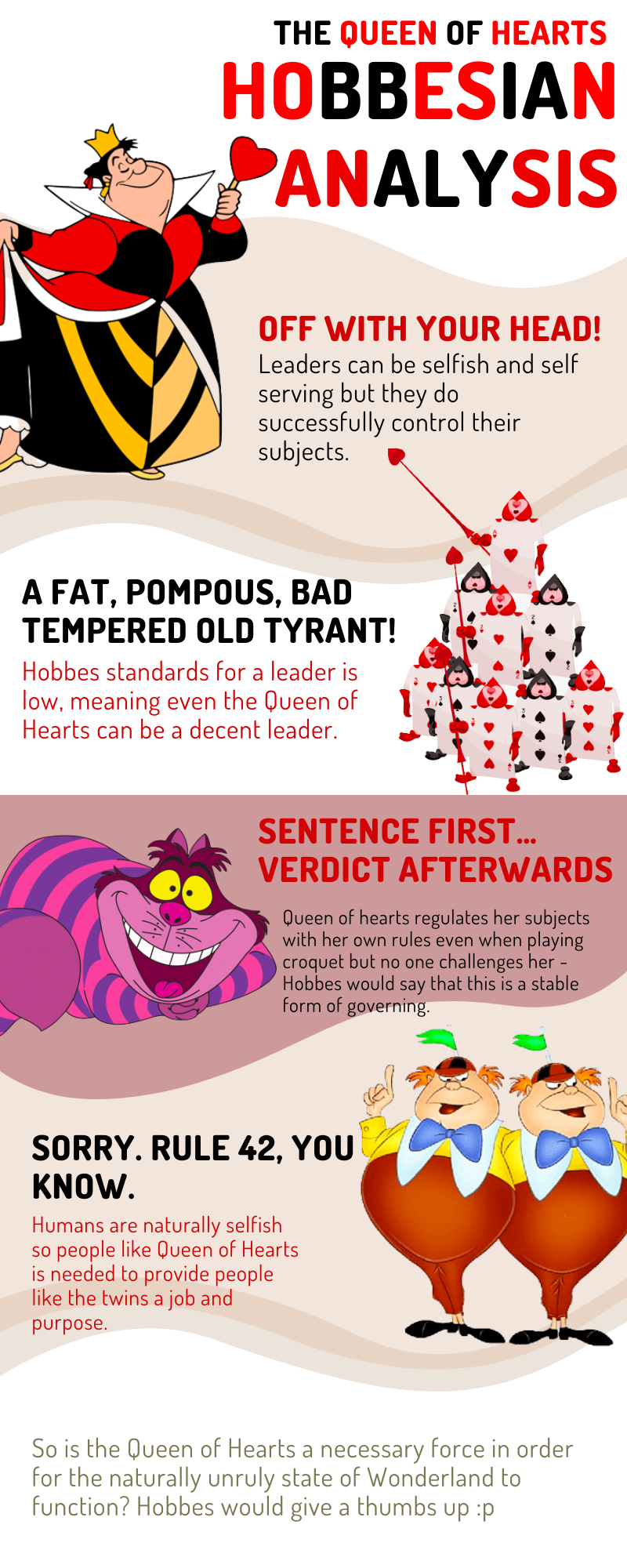

Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679): a true realist. Human nature is selfish, chaotic, and brutal. If I want what you have, I will kill you to get it. Hobbes believes that humans solely care about their own self-preservation. Because humans are so selfish (and we will just end up killing each other), we need a government to check our evil desires. For Hobbes, the bar for leadership is low… very low. If nature is chaotic and brutal, we must need a leader to keep people in check. However, we must not forget that leaders are selfish too! For Hobbes, even if we have a terrible leader, it is not worth overthrowing them because the alternative would just be a chaotic, brutal state of nature.

John Locke (1632–1704): humans aren’t nearly as terrible as Hobbes believes. We’re born a blank slate, but we tend towards the good. Riddled throughout Locke’s Second Treatise of Government is references to biblical allusions. So, we have a pretty good idea regarding Locke’s view of human nature: we’re born tabula rasa, but the human condition in one in which there are morals that must be followed to fulfill God’s will.

For Locke, there is natural law dictating unalienable rights. We have the right to life, liberty, and property. Fun fact: Founders in the U.S. changed this to “Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.” As Locke emphasizes private property heavily, he writes about why he believes it is an unalienable right. If there is an apple tree and I grab an apple, the effort I put into picking that apple makes that apple my property.

Because of these rights, the government must work to uphold those rights. Unlike Hobbes, if the government fails to uphold one’s alienable rights, individuals must take measures into their own hands. As one is born unto a social contract and is constructed as a liberal individual, liberal individualism guides our ethics.

Under a Lockean framework, does one need to help the less fortunate? Of course not. We don’t have to help others as long as we are preserving our own life, liberty, and property. As long as they have the right to life, liberty, and property, the government is doing its job.

Jean-Jaques Rousseau (1712–1778): humans are born good! But social institutions make humans terrible. Unlike Locke, Rousseau believes that social contracts dealing with liberal individualism fails. We shouldn’t focus on liberal individualism because we end up treating each other terribly (see example above of not helping the less fortunate). In fact, Rousseau believes that private property doesn’t exist in nature (a deviation from Locke) and believes that establishing private property leads to selfishness and greed.

Instead, Rousseau believes that we should craft a social contract with the collective. Rather than emphasizing life (like Hobbes) and property (like Locke), Rousseau is heavily concerned with liberty. He believes that we should view our bodies as one another’s property. If we were to view each other equally and craft a social contract among the people, Rousseau argues that this solves the problems that liberal individualism causes.

Continental Philosophy (19th-20th Century)

Karl Marx (1818–1883): a man with a nice beard concerned with historical materialism. Private property doesn’t exist — this is a human-made concept. When we believe that property is private, we capitalize on goods by hoarding goods creating a system of excess and waste. Instead, we must view history as dealing solely with class relations as all conflict stems from class relations. In this manner, governments only exist to regulate class relations. Marx views social relations through the lens of class (as all of our relationships with one another are mediated by class, according to Marx).

Postmodernism (1960’s-1970’s… maybe even today?)

Michel Foucault (1926–1984): a bald man concerned with power. For Foucault, the State is more than just a government ‘out there’ — the State exists within our heads. Becaues of this, power is embedded within every interaction we have with one another. We end up policing others to conform to social norms and get policed right back. Why are people afraid to dance in public? Why do you choose what clothes to wear? Why do you speak one way with your boss and one way with your teacher and one way with your friend?

Foucault utilizes Jeremy Bentham’s outline of a prison as a metaphor to describe the panopticon — a tool of discipline and punishment. In this prison, there is a watch tower with tinted windows at the center of a circle with prison cells facing towards it. From the prisoners perspective, they don’t know if they’re being watched. Because they might be being watched, they stop themselves from doing suspect activities. However, there is no one inside the watch tower. The prisoners police themselves. Foucault finds this prison to be replicative of ourselves.

In Discipline and Punish, Foucault writes: “the soul is a prison of the body.” Replace the word “soul” with “self.” The State requires your body for its functioning. You do things that you don’t want to do with your body in order to construct the self — i.e., you would rather be swimming than taking a test, but you have to take a test to construct the fact that you are an ideal-student. This makes us, who we truly are, prisoners to the self that is imposed upon us.

Is it possible to escape this system? Foucault doesn’t give an answer. Biopower (power over life) isn’t all that bad though — if the State says, “don’t eat rat poison,” you should probably listen. Foucault doesn’t claim that biopower is innately good or bad — he’s just making a descriptive claim about power.

And finally, for my high schoolers (many of whom debate various psychoanalytic arguments), I like to include my personal favorite philosophers who criticize Sigmund Freud and his predecessor Jacques Lacan:

Deleuze and Guattari (early to late 1900’s): two best friends debunking psychoanalysis. We can rid ourselves of the fascist within our heads, but it takes precision. Fascism is more than just Hitler during WWII. Fascism occurs on small scales in our day-to-day lives. We police everything from how we talk to how we dress to how we ‘act, feel, and think’. Like Foucault, they find these power structures to trap flows of desire. It’s pretty convenient here that Foucault wrote the preface to Anti-Oedipus. (I like to think of Deleuze and Guattari as providing a bit of a solution to the problems that stem from the power that Foucault discusses).

Deleuze and Guattari argue that we cannot solve for the macropolitical problems of the world, but we can solve for our day-to-day fascisms. They are concerned with desire: Dance when you can. Sing when you can. Draw and write when you can. Make art when you can. Do what you want. But be careful. “They won’t let you experiment in peace.” Some routes may be liberatory. Some routes may hurt you. And some routes may lead you to your death.

— — — —

So… Why write this blog post? Because we all know that philosophy is fairly inaccessible: many philosophies require an edifice of other philosophies to comprehend it, some of the literature is incredibly dense, and there are different types of philosophy with no clear starting point. From the ancient Greeks to the postmodernists , there is a necessity for educators to make these philosophies easily digestible.

Leave a Reply