An analysis of simple substances

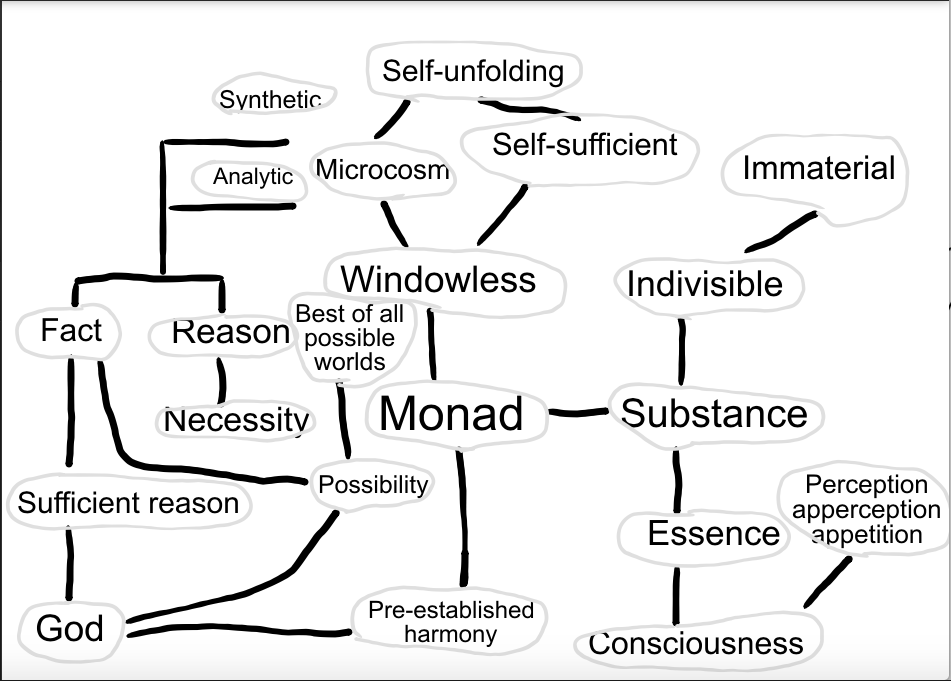

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716) was known as many things — scientist, philosopher, inventor of calculus (alongside Sir Isaac Newton), and diplomat. As one of the three great rationalist philosophers, alongside René Descartes and Baruch Spinoza, Leibniz was deeply invested in metaphysics and the pursuit of rational truth. His lifelong fascination with the nature of reality culminated in The Monadology, published in 1714. This text is both short and incredibly dense, composed of 90 propositions. The Monadology is one of the most ambitious metaphysical systems in Western philosophy. In this text, Leibniz posits a theory about the structure of the universe, the existence of God, and the harmony of all beings.

Leibniz’s ultimate aim was to reconcile religion, science, and general metaphysics within a single, coherent framework. His philosophical approach is best described as pluralist idealism, a significant departure from the substance dualism of Descartes and the substance monism of Spinoza. Rather than examining the entirety of Leibniz’s philosophy in this introduction, I analyze what I find to be the most important propositions in The Monadology.

For this post, I’m using Robert Latta’s 1898 English translation of The Monadology. The language is dated, but it is a faithful and widely used version that preserves the nuance of Leibniz’s thought.

Let us begin with the first proposition:

Proposition 1:

1. The Monad, of which we shall here speak, is nothing but a simple substance, which enters into compounds. By ‘simple’ is meant ‘without parts.’ (Theod. 10.) →

The concept of the monad has deep roots in Western philosophy. Its earliest appearance is found in ancient Greece, around the 6th century BCE, with the Pythagoreans. The term monas, meaning “one” or “unity,” was used to describe the origin of all numbers. Leibniz draws from this idea and expands upon it for his philosophical project.

For Leibniz, a monad is a “simple substance” — a fundamental, single unit of reality that has no parts. Although each monad exists independently, they can together form compounds. To gain further insight, we can turn to the third proposition:

Proposition 3:

3. Now where there are no parts, there can be neither extension nor form [figure] nor divisibility. These Monads are the real atoms of nature and, in a word, the elements of things. →

As stated earlier, monads have no parts, which means monads lack physical extension and cannot be divided. They are not located in space in the manner that material objects are. To give an example, consider a glass of water. The water is a compound composed of molecular elements such as hydrogen and oxygen. At first glance, one might be tempted to think of atoms as monads, but atoms occupy space and can be further divided into protons, neutrons, and electrons — each of which also takes up space. These, in turn, are composed of quarks, which still fall within the realm of spatial, divisible entities. For Leibniz, this ‘infinite’ regress of division implies the need for a truly simple substance — one that is not extended in space and cannot be broken down any further. This is the monad: the metaphysical foundation upon which physical reality is built.

Proposition 6:

6. Thus it may be said that a Monad can only come into being or come to an end all at once; that is to say, it can come into being only by creation and come to an end only by annihilation, while that which is compound comes into being or comes to an end by parts. →

Monads are indivisible, meaning they have no parts. Because of this, Leibniz argues that a monad cannot be assembled — it must come into existence all at once through creation. Likewise, since it has no parts to break apart, it can only cease to exist through annihilation. This contrasts with compounds, which are made of parts and can be assembled or dismantled gradually.

Proposition 7:

7. Further, there is no way of explaining how a Monad can be altered in quality or internally changed by any other created thing; since it is impossible to change the place of anything in it or to conceive in it any internal motion which could be produced, directed, increased or diminished therein, although all this is possible in the case of compounds, in which there are changes among the parts. The Monads have no windows, through which anything could come in or go out. Accidents cannot separate themselves from substances nor go about outside of them, as the ‘sensible species’ of the Scholastics used to do. Thus neither substance nor accident can come into a Monad from outside. →

Monads cannot be changed by anything external to them. Since a monad has no parts, nothing inside it can be altered or rearranged. This stands in contrast to compounds, which do have parts that can be added, rearranged, or taken away — allowing them to change in quality. One of the most well-known lines from The Monadology appears in this proposition: “Monads have no windows.” This means that nothing can enter or exit a monad, as they do not exist in space and have no internal parts.

Leibniz references Scholasticism, a medieval philosophical tradition that distinguished between substance (what a thing is; water, tree, etc.) and accidents (its qualities, such as color, temperature, or size). He argues that neither substances or accidents can enter or affect a monad from the outside. Ultimately, this seventh proposition argues that all change within a monad must arise from itself — following a pre-established development.

Let us consider an example. According to the Scholastic tradition, it would be proper to say that a pan becomes hot when placed on a stove, and that the heat is then transferred to cold water when the pan is submerged. However, Leibniz finds this explanation to be problematic. If heat — an “accident” — were something that could be passed from one substance to another, there would necessarily be a moment, however brief, when the heat exists in neither the pan nor the water, but somewhere in between. Leibniz argues change does not occur through the transfer of properties between substances, but arises internally within each monad. What appears as heat “moving” from the pan to the water is, in fact, a coordinated internal change within each monad. (We will get to this more explicitly soon.)

Proposition 8:

8. Yet the Monads must have some qualities, otherwise they would not even be existing things. And if simple substances did not differ in quality, there would be absolutely no means of perceiving any change in things. For what is in the compound can come only from the simple elements it contains, and the Monads, if they had no qualities, would be indistinguishable from one another, since they do not differ in quantity. Consequently, space being a plenum, each part of space would always receive, in any motion, exactly the equivalent of what it already had, and no one state of things would be discernible from another. →

Leibniz argues that monads must possess qualities; otherwise, they would not truly exist. If all monads lacked distinguishing qualities, they would be identical, resulting in a static and uniform universe. (This would entail change being impossible.) However, since compounds are made up of monads, any change we observe in compounds must reflect differences in monads themselves. And, because monads are immaterial and lack both size and shape, they cannot differ in quantity — only in quality.

When Leibniz refers to “space being a plenum,” he means that space is entirely full, with no empty gaps. Therefore, if all monads were identical, movement would produce no observable difference or change, and each region of space would always be filled with the same indistinguishable contents.

Proposition 9:

9. Indeed, each Monad must be different from every other. For in nature there are never two beings which are perfectly alike and in which it is not possible to find an internal difference, or at least a difference founded upon an intrinsic quality [denomination]. →

Building on the previous proposition, Leibniz emphasizes that all monads differ from one another in terms of quality. This idea reflects his principle known as the Identity of Indiscernables, which he explains more explicitly in his Discourse on Metaphysics (1686). According to this principle, no two entities can be exactly alike in every respect — specifically, monads. Each monad must possess some internal distinction or intrinsic quality that sets it apart from the others. Even if two monads appear similar, they are never truly identical.

Proposition 14:

14. The passing condition, which involves and represents a multiplicity in the unit [unité] or in the simple substance, is nothing but what is called Perception, which is to be distinguished from Apperception or Consciousness, as will afterwards appear. In this matter the Cartesian view is extremely defective, for it treats as non-existent those perceptions of which we are not consciously aware. This has also led them to believe that minds [esprits] alone are Monads, and that there are no souls of animals nor other Entelechies. Thus, like the crowd, they have failed to distinguish between a prolonged unconsciousness and absolute death, which has made them fall again into the Scholastic prejudice of souls entirely separate [from bodies], and has even confirmed ill-balanced minds in the opinion that souls are mortal. →

Leibniz explains that each monad perceives the world from its point of view. However, this does not mean that all monads are conscious. Instead, he distinguishes between perception (which all monads have) and apperception, or conscious awareness (which some monads have). He specifically criticizes Descartes’ view of consciousness where consciousness defines perception. Descartes’ famous phrase, “I think, therefore I am,” implies that only the thinking, conscious self can be certain of its existence, casting doubt on the reality of the external world. Leibniz problematizes this view because if human minds only counted as monads, then other living beings would have no soul.

For Leibniz, all living beings — and everything in the universe — is composed of monads, and he often refers to soul-like monads as “Entelechies” throughout The Monadology. He warns that the Cartesian perspective risks confusing unconsciousness with death. Just because a monad is not consciously aware does not mean that it lacks perception or is inactive. Furthermore, Leibniz challenges the Scholastic idea that souls are entirely separate from bodies, and he disagrees with the belief that the soul dies with the body. Since monads are indivisible and have no parts, they cannot decay like physical objects. A monad — whether it be solely perceptive or apperceptive — can only come into existence by creation and cease to exist by annihilation.

Proposition 17:

17. Moreover, it must be confessed that perception and that which depends upon it are inexplicable on mechanical grounds, that is to say, by means of figures and motions. And supposing there were a machine, so constructed as to think, feel, and have perception, it might be conceived as increased in size, while keeping the same proportions, so that one might go into it as into a mill. That being so, we should, on examining its interior, find only parts which work one upon another, and never anything by which to explain a perception. Thus it is in a simple substance, and not in a compound or in a machine, that perception must be sought for. Further, nothing but this (namely, perceptions and their changes) can be found in a simple substance. It is also in this alone that all the internal activities of simple substances can consist. (Theod. Pref. [E. 474; G. vi. 37].) →

Imagine a machine capable of thinking and feeling. Leibniz asks us to step inside this machine and examine its inner workings. From the observer’s perspective, all that is visible are mechanical parts interacting with one another — parts moving about. Yet, even in this advanced structure, nowhere can we find perception itself. There is no specific place in the machine where thought or feeling occurs. Leibniz argues that this shows perception cannot arise from physical mechanisms alone. Since machines are made of divisible parts and perception has no clear place among them, perception must come from something non-physical and indivisible — the monad.

Proposition 18:

18. All simple substances or created Monads might be called Entelechies, for they have in them a certain perfection (ἔχουσι τὸ ἐντελές); they have a certain self-sufficiency (αὐτάρκεια) which makes them the sources of their internal activities and, so to speak, incorporeal automata. (Theod. 87.) →

Leibniz borrows the term “Entelechy” from Aristotelian philosophy, where it refers to something that possesses its purpose or end within itself. He uses this concept to emphasize that monads are self-contained and completely independent. Monads do not rely on external forces to change. Instead, all of the monad’s activity comes from within. By calling monads “incorporeal automata,” Leibniz highlights that, although they are not physical machines, they operate like self-moving entities driven entirely by internal principles.

Proposition 21:

21. And it does not follow that in this state the simple substance is without any perception. That, indeed, cannot be, for the reasons already given; for it cannot perish, and it cannot continue to exist without being affected in some way, and this affection is nothing but its perception. But when there is a great multitude of little perceptions, in which there is nothing distinct, one is stunned; as when one turns continuously round in the same way several times in succession, whence comes a giddiness which may make us swoon, and which keeps us from distinguishing anything. Death can for a time put animals into this condition. →

Monads are always perceptive. Because they can only come into existence through creation and cease through annihilation, a monad must continue perceiving for as long as it exists. This is due to monads always being affected internally by their own nature; this internal affection is what Leibniz calls perception. He explains that some monads may experience a “great multitude of little perceptions,” meaning that their perceptions are so faint and numerous that they become indistinct. In these cases, the monad enters a stunned state, unable to distinguish between different sensations. Leibniz uses the example of spinning in circles, where continuous motion results in disorientation and unclear perception. He likens this to the death of animals. When an animal dies, the monad does not stop existing or stop perceiving. Rather, the soul-monad, or entelechy, continues to exist, but its perceptions are no longer clearly expressed.

Proposition 22:

22. And as every present state of a simple substance is naturally a consequence of its preceding state, in such a way that its present is big with its future. (Theod. 350.) →

This proposition shows that the current state of a monad is a natural result of its previous states, and that its future states are determined by its present condition. For Leibniz, this reflects a perfect internal order and progression. Since monads have no external influences, all change occurs through a continuous internal process. The harmony between monads arises because each follows its own internal development in sync with all others. For example, while one monad transitions internally from a perception of heat to cold, another will shift in a complementary manner from cold to heat. The coordination of these changes creates the appearance of interaction, even though no monad actually affects another.

Proposition 23:

23. And as, on waking from stupor, we are conscious of our perceptions, we must have had perceptions immediately before we awoke, although we were not at all conscious of them; for one perception can in a natural way come only from another perception, as a motion can in a natural way come only from a motion. (Theod. 401–403.) →

When examining perception, it is conscious perceptions are not a priori but rather stem from a previous perception. Leibniz illustrates this with the example of waking from sleep. Upon waking up, we become consciously aware, but this awareness must have developed from previous, unconscious perceptions during sleep. He compares this to motion, where any movement must be caused by a previous motion. In the same way, a conscious perception must naturally follow from a prior perception.

Proposition 27:

27. And the strength of the mental image which impresses and moves them comes either from the magnitude or the number of the preceding perceptions. For often a strong impression produces all at once the same effect as a long-formed habit, or as many and oft-repeated ordinary perceptions. →

Leibniz distinguishes between how perceptions are understood. There are perceptions related to magnitude, which refers to the strength of a perception. And there are perceptions of number, which refers to perceptions repeatedly being experienced over time. Current perceptions are influenced by both the magnitude and number of previous perceptions.

Proposition 28:

28. In so far as the concatenation of their perceptions is due to the principle of memory alone, men act like the lower animals, resembling the empirical physicians, whose methods are those of mere practice without theory. Indeed, in three-fourths of our actions we are nothing but empirics. For instance, when we expect that there will be daylight to-morrow, we do so empirically, because it has always so happened until now. It is only the astronomer who thinks it on rational grounds. →

Furthermore, Leibniz identifies two types of perception. The first type of perception is empirical perception, which is based on lived experience and habitual expectation. He associates this empirical perception with “lower animals,” as this kind of perception is rooted in lived experience. This is exemplified by the example given of the sun rising where people assume the sun will rise in the morning because it has always risen in the past. The second type of perception is rational perception, which is predicated from rational grounds. Unlike the average person, the astronomer is able to predict the sun will rise because of the specific laws pertaining to astronomy, rather than just past experience.

Proposition 29:

29. But it is the knowledge of necessary and eternal truths that distinguishes us from the mere animals and gives us Reason and the sciences, raising us to the knowledge of ourselves and of God. And it is this in us that is called the rational soul or mind [esprit]. →

Leibniz argues that there is an important distinction between humans and animals. Humans have the capacity to grasp “necessary and eternal truths,” which distinguishes us from animals. Humans are capable of reasoning and rational thought, unlike animals, allowing us to develop science and to have the knowledge of God through philosophical introspection.

Proposition 56:

56. Now this connexion or adaptation of all created things to each and of each to all, means that each simple substance has relations which express all the others, and, consequently, that it is a perpetual living mirror of the universe. (Theod. 130, 360.) →

This proposition is arguably the most famous within The Monadology. Since no monad can be affected by anything external, and each has internal qualities from within, Leibniz emphasizes that every monad unfolds according to a pre-established path. Returning to the example of heat transfer, one monad is internally programmed to change from hot to cold, while another is programmed to change from cold to hot. These changes do not result from interaction, but from a harmonious internal qualitative change. When Leibniz says each monad is a “perpetual living mirror of the universe,” he means that every monad reflects the entire universe from its own perspective. A change in the state of one monad corresponds to changes others — perhaps across the universe — because they are all coordinated in perfect harmony.

Proposition 57:

57. And as the same town, looked at from various sides, appears quite different and becomes as it were numerous in aspects [perspectivement]; even so, as a result of the infinite number of simple substances, it is as if there were so many different universes, which, nevertheless are nothing but aspects [perspectives] of a single universe, according to the special point of view of each Monad. (Theod. 147.) →

There is one universe composed of an infinite number of monads, each perceiving the same universe from its own perspective. Leibniz compares this to a town viewed from different angles and places. Depending on where one stands, the town appears differently, though it remains the same town. Similarly, each monad reflects the single universe from its specific point of view. With these countless perspectives, it appears that there are infinite universes, but Leibniz insists that each perspective is solely a unique perspective of the same universe.

Proposition 69:

69. Thus there is nothing fallow, nothing sterile, nothing dead in the universe, no chaos, no confusion save in appearance, somewhat as it might appear to be in a pond at a distance, in which one would see a confused movement and, as it were, a swarming of fish in the pond, without separately distinguishing the fish themselves. (Theod. Pref. [E. 475 b; 477 b; G. vi. 40, 44].) →

Leibniz explains that nothing in the universe is truly chaotic or lifeless, because every monad follows a pre-established path. All monads are active and continuously undergoing qualitative changes. What may appear to us as chaos is solely a question of perspective. To give an example, Leibniz compares the universe to a pond seen from a distance: the pond may look chaotic with the random movements of the water, but when one looks closer, they find that each fish is swimming purposefully.

Proposition 70:

70. Hence it appears that each living body has a dominant entelechy, which in an animal is the soul; but the members of this living body are full of other living beings, plants, animals, each of which has also its dominant entelechy or soul. →

Leibniz continues to explain that every living body possesses a dominant entelechy — a primary soul-like monad that governs it. In humans and animals, this entelechy is what we typically call the soul. But Leibniz does not stop there; he describes how living bodies are made up of other living beings, each of which also has its own entelechy. For instance, the human body is composed of organs, which are in turn made of cells, and so on, with each level made up of an infinite number of monads. These individual living units, such as cells, are themselves guided by their own dominant entelechies.

Proposition 87:

87. As we have shown above that there is a perfect harmony between the two realms in nature, one of efficient, and the other of final causes, we should here notice also another harmony between the physical realm of nature and the moral realm of grace, that is to say, between God, considered as Architect of the mechanism [machine] of the universe and God considered as Monarch of the divine City of spirits [esprits]. (Theod. 62, 74, 118, 248, 112, 130, 247.) →

The pre-established harmony that governs all monads extends beyond simple qualitative change. Leibniz introduces a second harmony — this time between two distinct realms. The first realm is the physical realm of nature, concerned with efficient causes, meaning that monads unfold through mechanical processes (as with an object in motion requiring a prior cause). The second realm is the moral realm of grace, concerned with final causes, where monads are directed towards purposes — specifically the divine purposes assigned by God to rational beings. In these realms, God acts both as Architect, designing the mechanistic structure of the universe, and Monarch, ruling over the spiritual order of entelechies. Unlike other philosophical systems that separate or oppose these realms, Leibniz insists they are perfectly harmonized. Thus, the universe is simultaneously governed by scientific laws and moral laws.

Proposition 88:

88. A result of this harmony is that things lead to grace by the very ways of nature, and that this globe, for instance, must be destroyed and renewed by natural means at the very time when the government of spirits requires it, for the punishment of some and the reward of others. (Theod. 18 sqq., 110, 244, 245, 340.) →

Leibniz argues that, because of the perfect harmony between nature and grace, all natural events — including catastrophic one — occur exactly when they are needed to fulfill a divine purpose. Events like the destruction or the renewal of the Earth align with God’s governance of souls. Therefore, nothing happens in nature without a reason grounded in justice. This propositions, and the general idea underlying The Monadology, is controversial. Horrific events, Leibniz says, must happen in order for the perfect universe to exist; and if these horrific events did not occur, then this universe would be worse off. (This does appear as a rationalist response to the Christian eschatological idea about the ‘end times’ or apocalyptic scenarios.)

Proposition 89:

89. It may also be said that God as Architect satisfies in all respects God as Lawgiver, and thus that sins must bear their penalty with them, through the order of nature, and even in virtue of the mechanical structure of things; and similarly that noble actions will attain their rewards by ways which, on the bodily side, are mechanical, although this cannot and ought not always to happen immediately. →

Leibniz argues that morality is embedded in the natural order of the universe. By describing God both as Architect (the designer of the physical world) and Lawgiver (source of moral law), he emphasizes that sins carry consequences and noble actions carry rewards — not through supernatural intervention — but through the mechanical structure of nature. Moral outcomes are already built into the structure of the universe, although Leibniz acknowledges that punishments and rewards do not manifest immediately.

Proposition 90:

90. Finally, under this perfect government no good action would be unrewarded and no bad one unpunished, and all should issue in the well-being of the good, that is to say, of those who are not malcontents in this great state, but who trust in Providence, after having done their duty, and who love and imitate, as is meet, the Author of all good, finding pleasure in the contemplation of His perfections, as is the way of genuine ‘pure love’, which takes pleasure in the happiness of the beloved. This it is which leads wise and virtuous people to devote their energies to everything which appears in harmony with the presumptive or antecedent will of God, and yet makes them content with what God actually brings to pass by His secret, consequent and positive [decisive] will, recognizing that if we could sufficiently understand the order of the universe, we should find that it exceeds all the desires of the wisest men, and that it is impossible to make it better than it is, not only as a whole and in general but also for ourselves in particular, if we are attached, as we ought to be, to the Author of all, not only as to the architect and efficient cause of our being, but as to our master and to the final cause, which ought to be the whole aim of our will, and which can alone make our happiness. (Theod. 134, 278. Pref. [E. 469; G. vi. 27, 28].)

The final proposition addresses the problem of theodicy — the question of how a good God can exist in lieu of a universe where evil exists. Leibniz argues that under God’s perfect governance and the pre-established harmony of monads, no virtuous action will go unrewarded and no sin will evade punishment. He defines the “good” as those who trust in God’s wisdom and act in accordance with their moral duties. Leibniz also distinguishes between two types of God’s will: antecedent will, which refers to actions that are generally good, like preventing suffering, and consequent will, which refers to the actions God permits (as God considers the overall harmony of the universe). The wise are those who strive to align with God’s antecedent will by acting virthously, while also accepting and trusting in God’s consequent will.

Conclusion

Ultimately, Leibniz’s metaphysics is both profound and enduring, captivating the minds of countless individuals for centuries. While his ideas are not without their critics, his vision of the universe continues to influence many. Whether or not his metaphysical framework is true remains a separate question, but Leibniz’s influence on metaphysics is undeniable.

Leave a Reply