From the types of philosophy to the distinction between impressions and ideas, Hume’s empiricism is foundational to the Western canon

David Hume (1711–1776) was a Scottish philosopher whose work profoundly shaped modern philosophy. He is especially influential for his contributions to empiricism — the view that knowledge derives from sensory experience. Hume is often regarded as one of the three great empiricists, alongside John Locke and George Berkeley.

In his effort to construct an empiricist philosophy, Hume first wrote A Treatise of Human Nature (1739–40), where he examined human psychology and rejected the notion that humans are born with innate ideas. His later work, An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding (1748), succinctly refines and presents the key arguments of the Treatise. Like other major rationalists and empiricists of his time — despite their deep disagreements — Hume employs a structured form of argumentation, dividing his work into 12 sections, each developing a distinct theme. This blog post will explore Hume’s empiricism as presented in Sections I–V — the core of his account of how all knowledge arises from experience. Each section is divided into numbered parts (paragraphs) that build upon one another. Since these parts are unnamed, I will assign titles to them for clarity.

I am using the Oxford World’s Classics edition of An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding, edited with an introduction and notes by Peter Millican. While I recommend reading Millican’s introduction for context, this blog will focus exclusively on Sections I-V.

With that being said, Hume begins…

Section I: Of the different Species of Philosophy

I. The Practical Approach to Philosophy

The one considers man chiefly as born for action; and as influenced in his measures by taste and sentiment; pursuing one object, and avoiding another, according to the value which these objects seem to possess, and according to the light in which they present themselves.

In the opening passage, Hume introduces two distinct manners in which moral philosophy — “the science of human nature” — may be approached. Hume elaborates on the first kind, an active philosophy concerned with virtue in practice. This approach is guided more by sentiment and emotion than by abstract reasoning. Thinkers such as Plato exemplify this tradition: they make virtue alluring, employing vivid examples and stories to inspire moral conduct rather than to prove it through argument.

II. The Rational Approach to Philosophy

The other species of philosophers consider man in the light of a reasonable rather than an active being, and endeavour to form his understanding more than cultivate his manners.

Hume contrasts the active philosophy with one that is highly rational. Philosophers of this kind seek to uncover absolute truths that form the foundations of thought, feeling, and moral judgment. Their concern lies with establishing stable principles rather than cultivating manners or sentiment. They view human nature as subject to speculation, aiming to ground morality and reason in universal principles.

III. An Appeal to “Easy” Philosophy

The easy and obvious philosophy will always, with the generality of [hu]mankind, have the preference above the accurate and abstruse … The feelings of our heart, the agitation of our passions, the vehemence of our affections, dissipate all its conclusions, and reduce the profound philosopher to a mere plebeian.

The general consensus, Hume notes, is that the simpler form of philosophy (one that elevates common sense and appeals to everyday understanding) stands above the abstruse kind. It reads easy, often through stories: the tale of prisoners in a cave, heroic epics, etc. This approach is also practical, offering clear guidance on how one ought to live. The rational or speculative philosophy, by contrast, often feels detached from lived experience. Even when the rational philosopher arrives at certain truths, those insights rarely shape behavior once they return to the world of action.

IV. The Fame of “Easy” Philosophy

The fame of Cicero flourishes at present; but that of Aristotle is utterly decayed. La Bruyere passes the seas, and still maintains his reputation: But the glory of Malebranche is confined to his own nation, and to his own age. And Addison, perhaps, will be read with pleasure, when Locke shall be entirely forgotten.

Not only is the easy kind of philosophy more accessible, but it is also more enduring. In the rational or abstruse approach, a single error can unravel the entire system — one flawed definition, axiom, or proposition can cause the whole structure to collapse. By contrast, the “easy” philosophers, such as Plato, build upon the shared sentiments and intuitions of human experience. If an error appears in their reasoning, it does not undermine the foundation; rather, it can be clarified or refined without destroying the project. Thus, while figures like Plato continue to endure through centuries, Hume suggests that thinkers like Locke — rooted in abstraction — will be forgotten.

V. The Perfect Balance

The most perfect character is supposed to lie between those extremes; retaining an equal ability and taste for books, company, and business… nothing can be more useful than compositions of the easy style and manner… By means of such compositions, virtue becomes amiable, science agreeable, company instructive, and retirement entertaining.

The “mere philosopher,” Hume notes, appears detached from society — withdrawn into contemplation and preoccupied with ideas that few can fully grasp. Yet the “mere ignorant” person fares even worse: in an age of enlightenment and scientific progress, a lack of intellectual curiosity marks a failure to engage with the world. These represent two extremes — one so absorbed in thought that he loses touch with reality, the other so disengaged that he cannot meaningfully participate in conversation or reflection. The ideal character, for Hume, lies between them: a person capable of moving between study and society, combining the discernment of learning with social interaction. Hume praises a style of philosophy that reflects this balance — a philosophy grounded in everyday life, joining reason with experience.

VI. A Balanced Life

Indulge your passion for science, says she, but let your science be human, and such as may have a direct reference to action and society.… Be a philosopher; but, amidst all your philosophy, be still a [hu]man.

Human life, Hume suggests, is governed by three central impulses: reason, activity, and sociability. A well-balanced life requires harmony among these. The rational being seeks intellectual nourishment through study and contemplation; the active being pursues work and practical engagement; and the social being thrives on interaction and conversation. Yet excess in any one of these leads to imbalance: too much studying breeds depression, excessive labor brings exhaustion, and constant socializing is boring for the mind. Philosophy must remain human — rooted in the ordinary life and situated between these three areas.

VII. Do Not Discard Abstruse Philosophy

But as the matter is often carried farther, even to the absolute rejecting of all profound reasonings, or what is commonly called metaphysics, we shall now proceed to consider what can reasonably be pleaded in their behalf.

Hume acknowledges that it would be harmless if most people simply preferred the easy philosophy to the abstruse, following whatever best suits their temperament. However, rather than merely favoring the accessible, many go further — actively condemning and rejecting the abstruse or “metaphysical” philosophy altogether. In response, Hume turns to defend this kind of philosophy, arguing that such philosophy remains necessary for deepening our understanding of the principles that serve as the foundation for knowledge.

VIII. Abstract Philosophy Supports the “Easy” Philosophy

The anatomist presents to the eye the most hideous and disagreeable objects; but his science is useful to the painter in delineating even a Venus or an Helen.

Although the abstract and the “easy” or humane traditions may seem opposed, Hume argues that the abstract philosophy provides the essential foundation upon which the humane kind depends. The humane philosopher can present arguments about virtue or life, but these perspectives must rely on a proper foundation — supplied by the abstract thinker. Hume gives an analogy: the abstract philosopher is like an anatomist, engaged in the necessary work of dissecting the human body; the humane philosopher is like a painter who relies on the anatomist’s knowledge to depict the body.

IX. Societal Benefits of Abstract Philosophy

And though a philosopher may live remote from business, the genius of philosophy, if carefully cultivated by several, must gradually diffuse itself throughout the whole society, and bestow a similar correctness on every art and calling.

Hume challenges the notion that abstract philosophy serves only the individual philosopher. Its true value lies in its broader social influence. Even if abstract thought appears impractical, it benefits society by cultivating habits of careful reasoning. These habits spread shape how people think and work across professions — from judges and lawyers to painters and politicians. Philosophers may live in isolation, but their ideas gradually diffuse through the culture. These newfound ideas improve the overall quality of human life.

X. The Pleasure of Abstract Philosophy

The sweetest and most inoffensive path of life leads through the avenues of science and learning; and whoever can either remove any obstructions in this way, or open up any new prospect, ought so far to be esteemed a benefactor to mankind.

Although Hume emphasizes the social benefits of abstract philosophy, he also argues that even without such benefits, abstract philosophy remains valuable for the pleasure it brings through intellectual curiosity. The search for knowledge is one of the few pleasures that is both safe and harmless: people grow in understanding without causing harm to others. For some minds, the effort required to grasp difficult ideas is itself rewarding (this blog being an example). While obscurity is painful and frustrating to the mind, philosophy’s task is to dispel that darkness.

XI. Metaphysics is Confusing

But this obscurity in the profound and abstract philosophy, is objected to, not only as painful and fatiguing, but as the inevitable source of uncertainty and error.

The strongest objection to Hume’s claim that abstract philosophy brings light to darkness is that abstract philosophycan be a source of confusion and error. Much of what is commonly called ‘metaphysics,’ is not genuine science but the product of human vanity and superstition. These false metaphysicians foster dogmatism and stifle genuine inquiry. Hume warns that abstract philosophy must be pursued with vigilance.

XII. Fighting False Philosophy

We must submit to this fatigue, in order to live at ease ever after: And must cultivate true metaphysics with some care, in order to destroy the false and adulterate.

Hume argues that false philosophy must be challenged. Rather than dismissing all metaphysical inquiry as obscure or erroneous, he insists that the proper response is to confront bad philosophy with proper reasoning. To truly understand metaphysics, we must examine the nature and limits of the human mind itself (rather than chasing after superstitious or speculative ideas). A disciplined and rigorous philosophy is the only effective remedy. Through such inquiry, we can expose problematic “metaphysics.”

XIII. Studying the Human Mind

It becomes, therefore, no inconsiderable part of science barely to know the different operations of the mind, to separate them from each other, to class them under their proper heads, and to correct all that seeming disorder, in which they lie involved, when made the object of reflection and enquiry.

Beyond challenging false philosophy, Hume argues that there are inherent benefits to studying the human mind. The difficulty lies in focusing: while mental operations are the closest things to us, they are also the most fleeting. When we try to reflect on a perception, idea, or sensation, it shifts and vanishes before we can grasp it. Hume finds that the philosopher’s task is to classify and distinguish the various powers of the mind — perception, imagination, emotion, and understanding. Such distinctions bring and clarity form the groundwork for a disciplined philosophy.

XIV. Science of the Mind = Certain

It cannot be doubted, that the mind is endowed with several powers and faculties, that these powers are distinct from each other, that what is really distinct to the immediate perception may be distinguished by reflection; and consequently, that there is a truth and falsehood in all propositions on this subject, and a truth and falsehood, which lie not beyond the compass of human understanding.

Hume rejects the claim that understanding the mind is impossible or uncertain. He argues that we can know that the mind operates through distinct faculties — such as the will, understanding, and imagination — and that these distinctions are as real as those found in any natural science. Hume likens this study to astronomy: just as the astronomer maps out celestial bodies, the philosopher maps the internal workings of the mind.

XV. Optimistic Future

But may we not hope, that philosophy, if cultivated with care, and encouraged by the attention of the public, may carry its researches still farther, and discover, at least in some degree, the secret springs and principles, by which the human mind is actuated in its operations?

Hume remains optimistic that the study of the mind may one day uncover the fundamental principles that govern its operations. Just as scientists have moved from observing natural phenomena to discovering the laws underlying them, the philosopher do the same with the mind — tracing its faculties back to their organizing principles. He holds that the mind’s operations are deeply interconnected, and that study may reveal these inner relations. Though success is uncertain, the pursuit itself is valuable. Like the politician who works to improve the structure of society despite uncertainty, the philosopher must continue their path of conceptualizing the mind’s operations.

XVI. A Difficult Examination

What though these reasonings concerning human nature seem abstract, and of difficult comprehension?

Nothing in Hume’s discussion suggests that studying the mind is an easy task. If it were, the greatest philosophers of antiquity would already have provided the answers. Though Hume calls for abstract investigations into human nature, we should not doubt the truths that are revealed from these inquiries. Whether through the pleasure of studying or the possibility of uncovering broader truths that shape human understanding, the pursuit of knowledge about the mind remains a worthwhile endeavor.

XVII. Bridging the Gap

Happy, if we can unite the boundaries of the different species of philosophy, by reconciling profound enquiry with clearness, and truth with novelty! And still more happy, if, reasoning in this easy manner, we can undermine the foundations of an abstruse philosophy, which seems to have hitherto served only as a shelter to superstition, and a cover to absurdity and error!

Hume concludes Section I by acknowledging that abstraction often makes philosophy overly complex . To address this, he explains that in An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding, he will present his ideas with clarity, making them readable. His aim is to bridge the divide between the “easy” and the “abstruse” forms of philosophy. This balance is essential to effectively convey his empiricist project.

Section II: Of the Origin of Ideas

I. Direct Sensations vs. Ideas

The most lively thought is still inferior to the dullest sensation.

Hume begins Section II by distinguishing between direct sensations and ideas. Direct sensations are the mind’s vivid perceptions — such as the pain of touching fire or the pleasure of gentle warmth. Ideas, on the other hand, are the faint images of these sensations when recalled by memory. Though we may almost feel the burn by thinking of it vividly, such representations never equal the severity or immediacy of the original sensation.

II. Reflecting Passion

… our thought is a faithful mirror, and copies its objects truly; but the colours which it employs are faint and dull, in comparison of those in which our original perceptions were clothed.

Not only does the distinction between direct sensations and ideas carry great weight, but it also extends to emotions and passions. Feeling anger or being in love is far more vivid and immediate than merely thinking about those emotions. For example, one may be told that someone is in love and understand what that means, yet such understanding lacks the intensity of the passion itself. The mind mirrors these feelings in thought, but always with diminished vivacity and intensity.

III. Two Classes of Perceptions

By the term impression, then, I mean all our more lively perceptions, when we hear, or see, or feel, or love, or hate, or desire, or will. And impressions are distinguished from ideas, which are the less lively perceptions…

Here, Hume formally introduces a classification between two types of perceptions. He begins by noting that the “less forcible” and “less lively” perceptions are commonly understood as thoughts or ideas. The second type consists of direct sensations, which he refers to as impressions. Perceptions of this latter kind arise directly from experience and possess greater vivacity than mere ideas.

IV. The Apperanace of Boundless Thought

And while the body is confined to one planet … thought can in an instant transport us into the most distant regions of the universe; or even beyond the universe…

The mind’s capacity for thought appears functionally limitless. While the body is constrained by pain, mobility, and the bounds of the physical world, thought easily transcends space and reality. The imagination can construct monsters, invent fictions, and conceive of worlds beyond the universe itself. Hume emphasizes that nothing lies beyond the reach of thought except what involves a logical contradiction.

V. Limitations on Thought

… all this creative power of the mind amounts to no more than the faculty of compounding, transposing, augmenting, or diminishing the materials afforded us by the senses and experience.

Although thought appears boundless (as Hume noted in the previous part), he argues that thought is ultimately constrained by experience. The imagination does not truly create new ideas but merely rearranges what the senses have already provided. For instance, to conceive of a golden mountain, one must first possess impressions of both gold and mountains. These impressions arise from direct experience, and the imagination simply combines them into one. Thus, even the most creative acts of thought are recollections of previous impressions — showing that ideas are copies of impressions and are weaker in force.

VI. All Ideas Derive from Impressions (pt. I)

… every idea which we examine is copied from a similar impression. Those who would assert, that this position is not universally true nor without exception, have only one, and that an easy method of refuting it; by producing that idea, which, in their opinion, is not derived from this source.

Hume offers two proofs to show that all ideas are ultimately derived from impressions, though in this passage he develops only the first. This proof concerns the content or composition of ideas. Upon examining any idea — no matter how abstract — we find that it can be traced back to simpler impressions. Even the idea of an infinite, all-good, and all-wise God arises by reflecting on our own limited wisdom and morality, then extending these qualities beyond all bounds. For anyone who disputes this claim, Hume issues a challenge: produce a single idea whose composition is not derived from some preceding impression.

VII. All Ideas Derive from Impressions (pt. II)

A blind [hu]man can form no notion of colours; a deaf [hu]man of sounds. Restore either of them that sense, in which [they are] deficient; by opening this new inlet for [their] sensations, you also open an inlet for the ideas; and [they] find[s] no difficulty in conceiving these objects.

Hume presents a second proof to demonstrate that all ideas are derived from impressions, drawing on examples of sensory deprivation. A person born blind can form no idea of color, lacking the impressions provided by sight. Likewise, someone born deaf cannot conceive of sound. Yet, if such a person were suddenly granted the missing sense, they would immediately gain the corresponding ideas — of color, music, and so on. Hume extends this logic to emotion as well: a person of impatient or selfish temperament cannot truly conceive of patience or other sentiments they have never experienced.

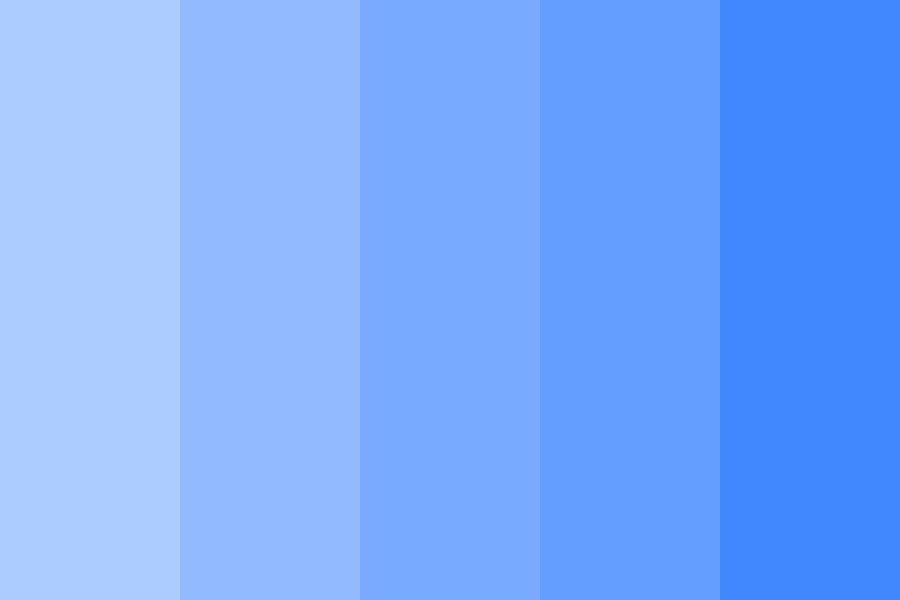

VIII. The Missing Shade of Blue

Let all the different shades of that colour, except that single one, be placed before [them], descending gradually from the deepest to the lightest; it is plain, that [they] will perceive a blank, where that shade is wanting, and will be sensible, that there is a greater distance in that place between the contiguous colours than in any other.

Hume introduces a thought experiment: imagine an individual who has lived for thirty years and is familiar with every color except one particular shade of blue. If presented with a gradient of all other blue tones — from the deepest to the lightest — this person would notice a blank spot where the missing shade should be. It seems possible that the person could imagine the missing color, even though they had never directly experienced it. This would be a case where an idea arises without a prior impression. Yet, Hume downplays the significance of this example, calling it too singular to challenge his general principle. (Still, one might interpret this as supporting Hume’s point: the mind could be combining adjacent impressions — the darker and lighter blues — to form a kind of “admixture,” meaning that this exception would still fit within his framework.)

IX. The Empirical Test

When we entertain, therefore, any suspicion, that a philosophical term is employed without any meaning or idea (as is but too frequent), we need but enquire, from what impression is that supposed idea derived?

Hume concludes this section by establishing a foundational principle for all philosophy: every idea must be traced back to its original impression. This method will prevent philosophers from becoming lost in obscurity or confusion during metaphysical speculation by grounding thought in experience. Hence Hume’s guiding question for any philosophical claim: “From what impression is that supposed idea derived?”

Section III: Of the Association of Ideas

I. The Principle of Connecting Ideas

And even in our wildest and most wandering reveries, nay in our very dreams, we shall find, if we reflect, that the imagination ran not altogether at adventures, but that there was still a connexion upheld among the different ideas, which succeeded each other.

Hume begins Section III by examining how ideas connect to one another. Ideas do not arise randomly; they follow a natural chain of order and connection. Whether in academic conversation, casual daydreams, or even dreams, thoughts proceed according to a kind of method. For example, a conversation about dogs might lead to a discussion of cartoons when the idea of Scooby-Doo arises. When this chain is disrupted — say, by an intrusive or unrelated thought — the break in order is immediately noticeable. This universal tendency reveals that the human mind operates through certain principles of connection among ideas. Hume notes that this phenomenon appears across all cultures and languages.

II. Three Principles of Association

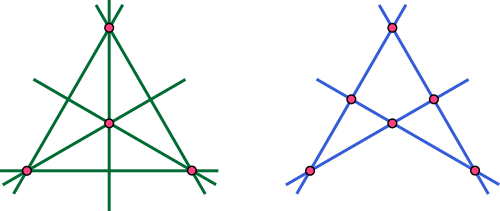

To me, there appear to be only three principles of connexion among ideas, namely, Resemblance, Contiguity in time or place, and Cause or Effect.

After examining the principle that connects ideas, Hume observes — humbly, of course — that no philosopher before him had systematically classified these principles of association. He identifies three basic forms of connection among ideas: resemblance, where one idea calls to mind another of a similar nature; contiguity, where ideas are linked through their proximity in time or place; and cause and effect, where one idea naturally leads us to another as its result or origin. Together, these form the fundamental pillars through which the mind organizes and unites experience.

III. Examples and Summary

A picture naturally leads our thoughts to the original: The mention of one apartment in a building naturally introduces an enquiry or discourse concerning the others: And if we think of a wound, we can scarcely forbear reflecting on the pain which follows it.

Hume concludes this section by illustrating how the three principles of association manifest in thought. Looking at a painting, for instance, might lead us to think of another similar one — this is resemblance. Mentioning one room in an apartment might bring to mind the whole complex — this is contiguity. And thinking of a wound naturally makes us reflect on the pain that follows — this is cause and effect. Hume acknowledges that it is difficult to prove these three principles are complete; there may be other principles of association. This uncertainty should inspire continued reflection on how the mind connects its ideas.

Section IV: Sceptical Doubts concerning the Operations of the Understanding

Since Section IV is split into two distinct parts, I’ll analyze them separately below, with individual titles for clarity.

Part I

I. Relations of Ideas

All the objects of human reason or enquiry may naturally be divided into two kinds, to wit, Relations of Ideas, and Matters of Fact.

Hume begins Section IV by distinguishing between two kinds of objects of human reason: relations of ideas and matters of fact. In this part, he only focuses on the first. Relations of ideas refer to propositions that are necessarily true and discoverable by thought alone — such as those found in mathematics and logic. Their truth is established purely through thought, independent of any existing thing in the world. For example, even if no triangle ever existed in nature, the Pythagorean theorem would still hold true conceptually. Its certainty arises from the relations between the ideas rather than discoverable objects in the real world.

II. Matters of Fact

That the sun will not rise to-morrow is no less intelligible a proposition, and implies no more contradiction, than the affirmation, that it will rise.

The second object of human reason is matters of fact. Unlike mathematical truths, matters of fact cannot be proven with absolute certainty. Their opposites are always conceivable without contradiction. Hume gives the example of someone saying, “the sun will rise tomorrow.” If another person says, “the sun will not rise tomorrow,” this is not a contradiction, since we have no demonstrative proof that the sun must rise. Our belief that it will do so rests on experience and habit.

III. Where Do Matters of Fact Come From?

The discovery of defects in the common philosophy, if any such there be, will not, I presume, be a discouragement, but rather an incitement, as is usual, to attempt something more full and satisfactory, than has yet been proposed to the public.

Hume emphasizes the necessity of examining how matters of fact arise. If it is true that such knowledge can never be certain, then we must ask how individuals come to believe in matters of fact at all. Beyond what we immediately perceive or remember, what gives us assurance that the sun will rise tomorrow? Hume points out that philosophers, both ancient and modern, have neglected this crucial question. Yet he insists this should not discourage us; rather, it should serve as a source of excitement.

IV. Cause and Effect → Matters of Fact

All reasonings concerning matter of fact seem to be founded on the relation of Cause and Effect.

All reasoning concerning matters of fact depend on the relation of cause and effect. Unlike relations of ideas — such as mathematical propositions — which are true a priori and can be known through pure reasoning, matters of fact depend on inference beyond direct experience. Hume illustrates this through examples: discovering a watch on a deserted island naturally leads one to infer that someone must have been on the island before before; believing that a friend lives in France requires some connecting evidence, such as a letter. One’s belief about something unobserved requires the assumption of a causal connection linking what we perceive to what we infer.

V. Finding the Source of Causality

If we would satisfy ourselves, therefore, concerning the nature of that evidence, which assures us of matters of fact, we must enquire how we arrive at the knowledge of cause and effect.

This section, though only a single sentence, captures the essence of Hume’s project. He asserts that if all matters of fact indeed depend on the notion of causality, then it becomes necessary to investigate how the relation of cause and effect is established in the first place.

VI. Experience is the Result of Causal Knowledge

I shall venture to affirm, as a general proposition, which admits of no exception, that the knowledge of this relation is not, in any instance, attained by reasonings à priori; but arises entirely from experience…

Hume argues that our knowledge of cause and effect is not a priori — like a mathematical truth that can be uncovered through pure reason — but a posteriori, derived only from experience. No amount of rational thought can reveal the hidden connections between objects. He explains that if a person were shown a completely new object, they would have no ability to infer its causes or effects through reasoning. To illustrate this, Hume invokes the example of Adam, the first man created by God: Adam could not have known that immersion in water would drown him or that fire would burn him. Such knowledge arises only after repeated experience reveals these conjunctions.

VII. Causation Cannot Be Discovered Through Reason

This proposition, that causes and effects are discoverable, not by reason, but by experience, will readily be admitted with regard to such objects, as we remember to have once been altogether unknown to us; since we must be conscious of the utter inability, which we then lay under, of foretelling, what would arise from them.

Hume reinforces his argument that causation can only be understood through experience. As in the previous section, he notes that when one encounters a new object, they cannot predict its causes or effects through reason alone. No one naturally or innately knows that gunpowder explodes. Even in natural phenomena — such as the way milk nourishes the human body — the connection between milk and its effect (nourishment) cannot be known without prior experience.

VIII. A Possible Objection

Such is the influence of custom, that, where it is strongest, it not only covers our natural ignorance, but even conceals itself, and seems not to take place, merely because it is found in the highest degree.

A potential objection to Hume’s argument is that while complex causal relations can only be understood through experience, simpler ones — such as a billiard ball setting another in motion — might be knowable through reason alone. Hume rejects this, explaining that such a view is an illusion produced by habit. From birth, we witness countless sequences of events, and over time it becomes second nature to infer causal connections. Yet, if we were suddenly placed into the world without prior experience, we would have no rational basis for assuming that one event would produce another.

IX. Cause and Effect Are Separated

The mind can never possibly find the effect in the supposed cause, by the most accurate scrutiny and examination. For the effect is totally different from the cause, and consequently can never be discovered in it.

All the laws of nature are known through experience alone. Hume presents a thought experiment: if one were shown an object without any prior experience of it, one could not predict what effects it would produce. Any such guess would be entirely arbitrary. This means that the effect is not contained within the cause — nothing in the first billiard ball’s motion reveals that it will move the second, nor does a stone held in the air disclose that it must fall when let go. Cause and effect are thus distinct events, and the belief in a necessary connection between them arises only from repeated experience.

X. The Illusion of Connection Between Cause and Effect

Why then should we give the preference to one, which is no more consistent or conceivable than the rest? All our reasonings à priori will never be able to shew us any foundation for this preference.

Hume furthers his critique of causality by showing that not only are cause and effect distinct events, but the belief that they are necessarily connected is an illusion. When one billiard ball strikes another, we easily imagine the second ball moving forward; yet, this outcome is not logically determined. Both balls might remain still, the second ball might go backwards or move in any direction. Each possibility is equally conceivable, because reason alone cannot demonstrate why one should occur rather than another. The moment we appeal to past experience to justify our expectation, we concede that causal knowledge is a posteriori — grounded in observation, not reason.

XI. Summary

In vain, therefore, should we pretend to determine any single event, or infer any cause or effect, without the assistance of observation and experience.

Hume summarizes his argument thus far by claiming that effects are distinct events from their causes. Any attempt to deduce effects from causes through reason alone is wholly arbitrary because the effect is not contained within the cause. Moreover, the effort to connect cause and effect is itself a product of habit rather than reason. This is the foundation of Hume’s empiricism: all causal knowledge depends entirely on experience, not on reason.

XII. Limitations on Understanding

The most perfect philosophy of the natural kind only staves off our ignorance a little longer: As perhaps the most perfect philosophy of the moral or metaphysical kind serves only to discover larger portions of it. Thus the observation of human blindness and weakness is the result of all philosophy, and meets us, at every turn, in spite of our endeavours to elude or avoid it.

Hume explains that there are strict limits to human understanding when it comes to discerning the true causes of things. Because the very notion of cause and effect is born out of habit, we can never grasp true cause behind natural events. The best humans can do is reduce phenomena to general patterns observed through repeated experience. Our greatest achievements in natural philosophy — such as identifying principles like gravity or cohesion — represent only descriptions of effects, not explanations of their underlying causes. Ultimately, Hume says that humans are ignorant.

XIII. Geometry Cannot Explain Causes

Geometry assists us in the application of this law, by giving us the just dimensions of all the parts and figures, which can enter into any species of machine; but still the discovery of the law itself is owing merely to experience, and all the abstract reasonings in the world could never lead us one step towards the knowledge of it.

Some may argue that geometry and mathematics offer insight into true causes, since they deal with relations of ideas rather than matters of fact. Hume challenges this by discussing “mixed mathematics”— applied mathematics used in natural philosophy — which merely assists experience rather than proving any underlying cause. Mathematics helps us describe and navigate causal relations, but it does not uncover the foundation that produces them. The laws that mathematics expresses, such as the principle of motion, are understood only through repeated observation. Abstract reasoning cannot isolate a necessary connection between cause and effect; it merely describes how things behave once those relations have been empirically established. Thus, even the most precise sciences ultimately depend on experience for their causal foundations.

Part II

XIV. Infinite Explanatory Regress

When again it is asked, What is the foundation of all our reasonings and conclusions concerning that relation? it may be replied in one word, Experience. But if we still carry on our sifting humour,* and ask, What is the foundation of all conclusions from experience? this implies a new question, which may be of more difficult solution and explication.

Hume initially asks, “What is the nature of our reasonings concerning matters of fact?” and establishes that such reasoning is grounded in the notion of causality. This naturally leads to a further question: what is the foundation of our belief in causality? His answer is experience. Yet Hume pushes the inquiry even deeper, asking what justifies our conclusions from experience itself. Why do individuals trust that the regularities observed in the past will continue into the future? With this question, Hume opens Part II of Section IV, arguing that this is the most difficult examination of all. He begins by advocating humility — acknowledging that the limits of human understanding demand modesty.

XV. Habit Over Reason

I say then, that, even after we have experience of the operations of cause and effect, our conclusions from that experience are not founded on reasoning, or any process of the understanding.

Hume shows humility in offering only a “negative answer,” concluding that our normative beliefs about cause and effect are not founded on reason. We can never truly know causal connections through understanding; we merely expect them through habit. Our belief that a particular effect will follow a cause arises from repeated experience rather than logical necessity, for reason alone cannot guarantee that one outcome must follow — any number of other effects might just as well occur.

XVI. Limits of Knowledge

The connexion between these propositions is not intuitive. There is required a medium, which may enable the mind to draw such an inference, if indeed it be drawn by reasoning and argument.

Hume continues by emphasizing how little the human mind understands the “hidden powers” or underlying principles behind observable qualities. We may see the color blue or feel the texture of a rock, yet we are never granted access to the metaphysical basis of how these things “act” as they do. Despite this ignorance, we nonetheless assume that things with similar appearances will behave in the same way — that the bread of tomorrow will nourish us just as the bread of yesterday did. This is the problem of induction: why do we assume the future will resemble the past merely because it always has?

XVII. A Promising Challenge

For this reason it may be requisite to venture upon a more difficult task; and enumerating all the branches of human knowledge, endeavour to shew, that none of them can afford such an argument.

Hume acknowledges that his “negative argument” — the claim that reasoning does not support causal inferences — might not yet convince everyone. He concedes that this is still new philosophical terrain, and some might suggest that the missing reasoning simply hasn’t been discovered yet. In response, Hume proposes to examine every branch of human knowledge, from mathematics to natural science, in order to show that none can provide such justification.

XVIII. Limitations of Demonstrative Reasoning

That there are no demonstrative arguments in the case, seems evident; since it implies no contradiction, that the course of nature may change, and that an object, seemingly like those which we have experienced, may be attended with different or contrary effects.

Hume distinguishes between two kinds of reasoning: demonstrative reasoning, which concerns relations of ideas, and moral reasoning, which concerns matters of fact. Some might argue that demonstrative reasoning could justify our belief in causal regularity, but Hume rejects this. It is always possible to imagine nature behaving differently — there is no contradiction in supposing that what appears to be snow could taste like salt. Since such views are conceivable without contradiction, no demonstrative or a priori argument can prove that the future must resemble the past.

XIX. Probable Reasoning Is Circular

To endeavour, therefore, the proof of this last supposition by probable arguments, or arguments regarding existence, must be evidently going in a circle, and taking that for granted, which is the very point in question.

After examining the failure of demonstrative reasoning to justify causal regularity, Hume turns to moral reasoning — that is, reasoning about matters of fact. This kind of reasoning assumes that the future will resemble the past: the sun rose yesterday, so it will rise today. Yet this assumption already depends on the very principle of cause and effect that we are trying to justify. The reasoning is circular, since we explain our belief in causal regularity by appealing to past experience, which itself relies on that same regularity. Moreover, there are no contradictions in imagining alternative outcomes, such as the sun failing to rise, which shows that reason provides no proof for expectations about the future.

XX. Similarity and the Limits of Reason

From causes, which appear similar, we expect similar effects. This is the sum of all our experimental conclusions … I cannot find, I cannot imagine any such reasoning.

Hume now turns from exposing the failures of reasoning to examining why we actually trust experience. All arguments from experience depend on the similarity we observe among natural objects: we expect similar effects to follow from similar causes. Hume insists that a philosopher must ask what principle of human nature gives experience its authority. If this trust were founded on reason, it would arise immediately from a single instance, (since logic does not necessitate repetition). Yet, in practice, our confidence only grows after many consistent experiences. This gradual strengthening shows that habit, not reasoning, leads us to expect regularity. Hume concludes modestly, saying he cannot find the reasoning that would justify this process — but remains open to correction if anyone can provide a legitimate argument.

XXI. Why Expect the Future to Resemble the Past?

It is impossible, therefore, that any arguments from experience can prove this resemblance of the past to the future; since all these arguments are founded on the supposition of that resemblance.

Hume explains that experience teaches us to expect certain qualities and effects from objects. For instance, I conclude that eating bread will nourish me because it has done so countless times before, and this repetition appears to justify my expectation. Yet, upon closer scrutiny, this expectation rests only on habit, not reason. There is no logic or demonstration that guarantees this outcome — we never perceive the “secret powers” of bread by observing it. It is only after eating that we experience its effects. Experience shows us only repeated conjunctions between similar objects, never a necessary connection. Hume identifies this reliance on past experience to justify future expectations as circular: we use past experience to prove that our past experience of predicting the future is a reliable guide.

To clarify, when I say the sun will rise tomorrow, I justify this by recalling the past; every time I predicted the sun would rise, it did. But this reasoning only appeals to past experience to prove that past experience is a reliable guide to the future.

XXII. Having Philosophically Modesty

I must confess, that a [hu]man is guilty of unpardonable arrogance, who concludes, because an argument has escaped his own investigation, that therefore it does not really exist.

After presenting and establishing the problem of induction, Hume explains that it would be arrogant to assume that no solution to a philosophical problem exists simply because we have not yet discovered it. However, he says his argument is different: his reasoning is grounded in an examination of the limits of human knowledge. Hume’s skepticism about causal reasoning is well-founded.

XXIII. The Experience of Infants and Animals

If you assert, therefore, that the understanding of the child is led into this conclusion by any process of argument or ratiocination, I may justly require you to produce that argument

In concluding Section IV, Hume observes that even infants and animals learn from experience. When a child touches the flame of a candle and feels pain, they quickly internalize the idea that touching objects of a similar nature will produce the same effect. Yet the child does not arrive at this conclusion through abstract reasoning. The inference from cause to effect must therefore arise from experience alone. If one were to insist that reasoning guides the child’s understanding, they would then bear the burden of proving that the child engages in a process of abstract thought to learn not to touch fire.

Section V: Sceptical Solution of these Doubts

Since Section IV is split into two distinct parts, I’ll analyze them separately below, with individual titles for clarity.

Part I

I. The Innocence of Academic Philosophy

There is, however, one species of philosophy, which seems little liable to this inconvenience, and that because it strikes in with no disorderly passion of the human mind, nor can mingle itself with any natural affection or propensity; and that is the Academic or Sceptical philosophy.

Hume begins Section V by contrasting two kinds of philosophical temperaments. He warns that even philosophy, like religion, can corrupt its own purpose when misapplied. What aims to cultivate virtue may instead sustain vanity, selfishness, or egotistical behavior. However, Hume identifies that academic or skeptical philosophy escapes this. Unlike other systems, it aligns with no passion or self-interested end. Skepticism refuses to treat philosophy as an egotistical pursuit. Yet, the very innocence of this approach — its openness to error and willingness to be challenged in the pursuit of truth — invites hostility. People resent skeptical philosophy because it refuses to justify their vices.

II. Nature > Doubt

Nature will always maintain her rights, and prevail in the end over any abstract reasoning whatsoever.

Hume clarifies that skeptical philosophy does not — and should not — undermine the practical reasoning of everyday life. While philosophy may reveal gaps in human understanding, this does not require us to reject norms and customs because their foundations are uncertain. Nature will continue to do what nature does, regardless of our doubts. The challenge is not to eliminate instincts — such as the tendency to form beliefs through habit — but to understand their foundation.

III. Thought Experiment pt. I

[They] would not, at first, by any reasoning, be able to reach the idea of cause and effect; since the particular powers, by which all natural operations are performed, never appear to the senses…

Here, Hume introduces a thought experiment: imagine a person endowed with the strongest powers of reason suddenly brought into the world. This person would observe events as they happen but would be unable to grasp the concept of cause and effect. They would see one thing follow another yet find no reason to believe one event produces the next. The hidden powers that couples causes to effects are never revealed to the senses. Without repeated experiences linking events together in sequence, the mind would have no basis for forming expectations about what comes next. Thus, causation cannot be discovered through reason alone — it must be formed from experience.

IV. Thought Experiment pt. II

Yet [they have] not, by all [their] experience, acquired any idea or knowledge of the secret power, by which the one object produces the other; nor is it, by any process of reasoning, [they are] engaged to draw this inference.

Hume extends his thought experiment: once this individual with the strongest faculties gains experience — after repeatedly observing similar events occurring together — they begin to infer that one event causes another. Witnessing this constant conjunction, the mind naturally expects certain events to follow others. Yet even with all the experience imaginable, this person still lacks any rational insight into the hidden power that connects these events. The inference of causation cannot arise from reason alone.

V. Custom/Habit

All inferences from experience, therefore, are effects of custom, not of reasoning.

Hume finally names the principle that explains why we infer cause and effect: custom, or habit. When repeated experiences form a tendency in the mind to expect one event after another, this expectation is the product of custom. This does not reveal the ultimate reason behind the tendency; it only identifies a feature of human nature. The mind, conditioned by repetition, learns to expect certain outcomes — such as one’s hand burning when placing it onto a hot stove. One instance teaches nothing, but many repeated instances establish conviction.

VI. The Guide to Life

Custom, then, is the great guide of human life. It is that principle alone, which renders our experience useful to us, and makes us expect, for the future, a similar train of events with those which have appeared in the past.

Custom is the foundation of all human life. Through habit, experience becomes meaningful, allowing us to form beliefs about causality. Without custom, we would remain trapped in the immediacy of the moment, unable to connect past events with future expectations. Without custom, both life and reason would collapse into stillness .

VII. An Important Qualification

But here it may be proper to remark, that though our conclusions from experience carry us beyond our memory and senses, and assure us of matters of fact, which happened in the most distant places and most remote ages; yet some fact must always be present to the senses or memory, from which we may first proceed in drawing these conclusions.

Hume establishes an important qualification to his argument. While custom or habit allows us to infer beyond immediate experience, every inference must begin from something present to the senses. For example, I might infer that a wobbly table could collapse and break my laptop, requiring repairs that would cost money. Yet to form this chain of expectation, something must be given in the present — the wobbly table itself. Hume illustrates this through historical examples: a historian or archaeologist can only infer past civilizations from the material traces that remain. Every act of reasoning must ultimately be anchored in experience.

VIII. Belief = Two Elements

All belief of matter of fact or real existence is derived merely from some object, present to the memory or senses, and a customary conjunction between that and some other object.

Every belief about matters of fact depends on two elements: a present impression — an object immediately given to the senses — and a customary conjunction that links this object to an expected outcome. When we encounter a flame, we naturally expect heat. In this way, belief is not a product of reasoning but a natural disposition of the mind, formed through repeated experience.

IX. Continued Philosophical Inquiry

But still our curiosity will be pardonable, perhaps commendable, if it carry us on to still farther researches, and make us examine more accurately the nature of this belief, and of the customary conjunction, whence it is derived.

Hume admits that this might be a reasonable place to conclude his inquiry — what more can we do once we have reached the limits of human understanding? Yet he insists that it is commendable to continue examining the nature of belief. Even if such analysis yields no final certainty, the examination is worthwhile for the insights they may reveal.

Part II

X. Imagination

We can, in our conception, join the head of a [hu]man to the body of a horse; but it is not in our power to believe, that such an animal has ever really existed.

At this juncture, Hume distinguishes between belief and imagination. The imagination is boundless, capable of combining and rearranging ideas in infinite ways. Yet belief differs from imagination in one crucial respect — belief cannot be produced at will. We cannot simply choose to believe what we imagine. Whether it is a unicorn or a centaur, no matter how vividly conceived, we cannot convince ourselves that such creatures truly exist. Belief lies beyond mere conception; it carries a force of conviction that imagination cannot supply.

XI. Belief as an Excitation of Nature

It follows, therefore, that the difference between fiction and belief lies in some sentiment or feeling, which is annexed to the latter, not to the former, and which depends not on the will, nor can be commanded at pleasure.

Hume concludes that the distinction between belief and imagination is not a question regarding the content of ideas but the sentiment attached to belief. Take two ideas: the idea of a unicorn and the idea of the sun rising tomorrow. The content of these concepts does not matter as much as the sentiment one has in believing these concepts. Custom entails a sentiment that follows two connecting ideas: one can have the idea of the sun rising tomorrow and custom allows for the belief that the sun will rise tomorrow.

XII. The Impossibility of Defining Belief

I say then, that belief is nothing but a more vivid, lively, forcible, firm, steady conception of an object, than what the imagination alone is ever able to attain.

Belief is difficult to define because it is a feeling rather than a concept. This feeling distinguishes belief from imagination. Believed ideas carry a liveliness that imagined ones lack; believed ideas shape both our passions and our actions. Hume illustrates this with an example: when we hear a familiar voice from another room, we immediately believe that our friend is nearby. That belief feels far more vivid and real than imagining a mythical castle (even though both are products of the mind).

XIII. Theory of the Mind

… the sentiment of belief is nothing but a conception more intense and steady than what attends the mere fictions of the imagination, and that this manner of conception arises from a customary conjunction of the object with something present to the memory or senses…

Hume begins to conclude his account of belief by framing it as an intense and vivid feeling that distinguishes it from imagination. Belief arises through the customary conjunction between an impression and an idea — a link formed by experience and habit. From here, Hume gestures toward a general theory of the mind, suggesting that the same principles of custom and association that produce belief may govern many other mental operations.

XIV. Belief and the Principles of Association

These principles of connexion or association we have reduced to three, namely, Resemblance, Contiguity, and Causation; which are the only bonds, that unite our thoughts together, and beget that regular train of reflection or discourse, which, in a greater or less degree, takes place among all [hu]mankind.

Hume recalls his earlier discussion of the three principles of association — resemblance, contiguity, and causation — which organize how ideas flow from one idea to another. Thus far, he has only focused on causation to explain belief (repeated experiences make one believe in expected outcomes). Hume now asks: Could the feeling of believe also occur through resemblance and continuity? For example, if one sees a painting that reminds them of their friend, does belief play a role here (i.e., belief in a friend’s existence)? Or when one thinks of their apartment and then recalls about the street their apartment is on, is the feeling of belief operating here? Here, Hume suggests that the operations of belief are not only unique to causation, but part of a pattern that governs the human mind.

XV. Belief and Resemblance

We may, therefore, observe, as the first experiment to our present purpose, that, upon the appearance of the picture of an absent friend, our idea of him is evidently enlivened by the resemblance, and that every passion, which that idea occasions, whether of joy or sorrow, acquires new force and vigour.

Hume begins his first test to determine whether belief’s liveliness and feeling extend to resemblance, one of the three principles of association. He offers the example of seeing the picture of an absent friend. The resemblance between the image and the person enlivens the idea of that friend — the thought feels immediate and vivid. However, if the picture bears no likeness to the friend, such as a painting of a distant landscape, the mind loses this vividness of the friend. The liveliness of belief depends on resemblance only when joined with a present, resembling impression.

XVI. Religion and Resemblance

Sensible objects have always a greater influence on the fancy than any other; and this influence they readily convey to those ideas, to which they are related, and which they resemble.

Religion serves as a crucial example in proving that resemblance does enliven ideas. Hume observes how ceremonies of the Roman Catholic religion — rituals, gestures, and images — serve to make spiritual concepts more vividly present. Religious devotees affirm that these practices are necessary for strengthening their beliefs. Physical objects animate belief much more vividly than abstract ideas. Thus, resemblance, when coupled with an impression, enlivents belief.

XVII. Belief and Contiguity

The thinking on any object readily transports the mind to what is contiguous; but it is only the actual presence of an object, that transports it with a superior vivacity.

Hume extends his analysis to contiguity, the final principle of association. Just as resemblance enlivens thought and belief, proximity — whether spatial, emotional, etc. — intensifies the vividness of our ideas. Distance, by contrast, weakens them. When one is only a few blocks from their home, their belief of home feels more immediate and real than when they are hundreds of miles away. Even thinking of something near one’s home, such as one’s street or address, entails stronger impression of it. The closer one is to an object, the livelier one’s conception becomes. Thus, like causation and resemblance, contiguity strengthens belief by linking one’s ideas to something immediately present to the mind.

XVIII. Belief and Causation

No one can doubt but causation has the same influence as the other two relations of resemblance and contiguity.

In this part, Hume reiterates that causation is akin to resemblance and continuity in strengthening belief. He gives the example of religious relics — such as the clothing of saints — being valuable to religious people because these relics were once causally connected to saints. This causal connection makes the saint feel more vivid than the general thought of their clothing. Thus, causation enlivens belief.

XIX. Another Example

Suppose, that the son of a friend, who had been long dead or absent, were presented to us; it is evident, that this object would instantly revive its correlative idea, and recal to our thoughts all past intimacies and familiarities, in more lively colours than they would otherwise have appeared to us.

Hume offers one final example to show how the principles of association strengthen belief. If one were suddenly to meet the son of a friend long dead or absent, the sight would carry an intense vividness, bringing the friend’s presence back to mind. This illustrates how associative relations infuse certain thoughts with liveliness. Through these connections, memory and belief gain vivid force, allowing ideas to feel emotionally charged and immediate.

XX. Uniting the Principles

This is the whole operation of the mind, in all our conclusions concerning matter of fact and existence; and it is a satisfaction to find some analogies, by which it may be explained.

Hume concludes his argument that the principles of association strengthen belief. Whether it be resemblance, contiguity, or causation, the enlivening and vividness of thought presupposes belief in the related object’s existence. A picture of a friend only brings vivid emotions if one is to believe that their friend existed in the first place; nearness to one’s home only carries with it feeling if one believes their home to exist. Custom and habit underlies all belief.

XXI. Pre-Established Harmony

Custom is that principle, by which this correspondence has been effected; so necessary to the subsistence of our species, and the regulation of our conduct, in every circumstance and occurrence of human life.

Hume observes a kind of pre-established harmony between the course of nature and the flow of our thoughts. The hidden powers that govern the world may be beyond our understanding, yet the mind seems to move in accordance with them. Through custom, impressions and ideas become linked, allowing our thinking to mirror the order of nature. Without this principle, our knowledge would remain trapped within the limits of immediate perception, leaving us unable to anticipate, plan, or act. For Hume, custom is the foundation of belief and the condition for human life and survival.

XXII. Belief as Instinct

As nature has taught us the use of our limbs, without giving us the knowledge of the muscles and nerves, by which they are actuated; so has she implanted in us an instinct, which carries forward the thought in a correspondent course to that which she has established among external objects; though we are ignorant of those powers and forces, on which this regular course and succession of objects totally depends.

Hume concludes Section V by arguing that inference must arise from a natural instinct. Nature gives us the ability to use our limbs without first understanding the knowledge of muscles, nerves, and mobility; this same logic applies to custom and habit. Though we do not have the capacity to understand the hidden powers behind external objects and events, we can safely say that the mind follows specific patterns due to the particular principles of association.

Conclusion

There’s a reason Hume’s empiricism has endured for centuries. His analysis is incredibly precise, combining examples with clarity. While this blog does not cover the entirety of An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding, it outlines the central tenets of his empiricism — how belief, custom, and human understanding are bound together by nature itself. If you made it this far, it should be clear that Hume rightfully holds an essential spot in the Western philosophical canon.

Leave a Reply