“What is communism?” A beginner’s guide to Marx, Engels, and the origins of communism

Communism. It’s a word loaded with controversy and assumptions. But why does it carry such baggage? I have heard many individuals criticize communism — on the news, from family members, and even students — often without a clear understanding of what it actually means. In this blog post, I aim to provide a brief history of communism. No, I will not argue for or against it, but rather, I will simply explain what it is.

The history lesson begins…

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels (Mid 1800s)

Karl Marx (1818–1883) and Friedrich Engels (1820–1895) were influential philosophers and political economists. Together, they published The Communist Manifesto in 1848. Before diving into the text itself, let’s first take a closer look at its authors — starting with Marx.

Marx is well-known because he wrote… a lot. Across thousands of pages, he analyzed capitalism. Capitalism is the system we live in today, where private individuals and businesses own the means of production (i.e., the tools, factories, land, or resources needed to make goods and services), with the aim of increasing profits.

For example, an individual might own a business that produces shoes. They own the factory, the machines, and the raw materials. The workers in this factory simply sell their labor in exchange for a wage. But because the business owner’s goal is to generate profit, the business owner must sell the shoes at a higher price than it cost to produce them. And, the business owner must pay the worker less than the worker’s actual worth in order to generate profit. This gap between what the worker is paid and what the product sells for is an important point in Marx’s critique — he called this surplus value.

One common myth is worth dispelling upfront: Marx wasn’t just seeking to say that capitalism is “bad.” His goal was not primarily moral, but scientific. He analyzed the system of capitalism, finding out where it thrives and where is fails. Specifically, Marx was concerned with the internal contradictions of capital accumulation. These “contradictions” refer to the built-in tensions that could cause capitalism to collapse. For example: if the rich keep getting richer through the exploitation of the workers — meaning that the workers get paid less and less — who’s left to buy the products being sold? What happens when monopolies consolidate power and kill competition? (As you know, only one person can win Monopoly). Or, a contradiction more pressing today: if capitalism depends on infinite growth, with businesses needing to make more and more profit every year, but the Earth has finite resources, what then?

Marx first met Friedrich Engels in 1842 at the offices of Rheinische Zeitung, a radical newspaper. However, their true partnership didn’t begin until 1844, when they reconnected in Paris and developed a close intellectual bond. Engels recognized the importance of Marx’s work and believed his writing was essential to the liberation of the working class. Unfortunately, Marx struggled financially for much of his life. He faced high living costs, had a large family to support, and dealt with frequent health issues. Publishing his work was also a challenge. As a result, Engels supported Marx financially for many years.

This isn’t to diminish Engels’ own intellectual contributions — he was a profound thinker in his own right and co-developed much of what we now call Marxism. But it’s important to note that without Engels’ support, Marx likely could not have completed his most important work, Das Kapital, a three-volume critique of political economy — two of which were published posthumously.

Ultimately, Marx and Engels believed that the internal contradictions of capital accumulation would get so bad that the masses would overthrow those who own the means of production. Thus, they published the Communist Manifesto to liberate the masses.

The Communist Manifesto (1848)

The Communist Manifesto (1848) is a short read. It wasn’t written as a dense academic treatise, but as a pamphlet for the working class. Anyone can pick up the text and read it, and perhaps even be inspired to overthrow those who own the means of production.

Marx and Engels begin the manifesto by writing:

The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles.

This reflects the framework of historical materialism in Marxism. At its core, historical materialism holds that societies evolve through class conflict. In each historical era, there is a struggle between opposing social classes: slaves versus masters in ancient societies, serfs versus lords in feudalism, and in capitalism, the proletariat (those who do not own the means of production) versus the bourgeoisie (those who do).

A key element of Marxist thought is the idea that the working class would eventually “wake up” — developing what Marx called class consciousness — and collectively spark a global revolution. Marx believed this process would begin in advanced industrial capitalist economies like Britain or Germany, where capitalism had developed the most and its internal contradictions were most volatile.

Because workers in these societies had access to technology, education, and shared workplaces, they were more likely to recognize their collective exploitation and organize against it. Once revolution began in these countries, Marx and Engels believed the revolution would spread globally, inspiring other workers around the world to rise up. But this raises an important question: what comes after capitalism?

The answer, for them, was communism. Communism is a classless, stateless society where the means of production are owned by everyone. This world is free of exploitation because there is no conflict between the the proletariat and the bourgeoisie. And, the world would be free of government as we know it today. Marx and Engels believed that the state exists primarily to mediate class conflict. To illustrate this: imagine someone steals your pair of shoes. In our current system, you’d call the police, and that person might be arrested or punished. But why did they steal in the first place? Maybe to sell them for money? Or maybe they couldn’t afford their own? However, in a society where everyone has what they need, the conditions that create theft disappear. In such a world, communal cooperation would replace coercive authority, and the state would cease to exist.

Now, before you stop reading and dismiss communism as a utopian dream, consider this: capitalism is a very new system in human history. I often tell my students this: If you had a time machine — and the ability to speak the language — and you asked someone from the Paleolithic or Neolithic period whether transitioning to capitalism was possible, they would laugh and discard the idea as nonsense. The idea of private property, surplus value, and profit would be foreign to them. And yet, if you ask a capitalist today whether a form of communal living is possible, they’d also laugh and discard the idea as nonsense.

What seems impossible now might be common sense later. Might anything happen?

Vladimir Lenin (Early 1900s)

Vladimir Lenin (1870–1924) was inspired by The Communist Manifesto, which played a major role in shaping his revolutionary politics. In 1917, he led the October Revolution — also known as the Bolshevik Revolution — overthrowing Russia’s Provisional Government and establishing the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). (The USSR was formally established in 1922). Lenin remained in power from 1917–1924.

While Lenin agreed with the overall vision of Marx and Engels, he disagreed with their idea of how revolution would come about. For Lenin, it was unrealistic to believe that the masses would spontaneously rise up and spark a global revolution on their own. Instead, he argued that revolution needed to be guided and informed. This is where Lenin introduced the idea of a vanguard party. This party was an organized group of professional revolutionaries who would lead the proletariat. Like any political party, the vanguard would give people a clear platform, a clear set of demands, and leadership capable of confronting the existing system.

Lenin wrote an influential text titled Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism, where he explored why the revolution predicted by Marx and Engels had not yet occurred. He argued that capitalism in advanced industrial Europe had been temporarily stabilized by imperialism. By exploiting the Global South for raw materials, cheap labor, and new markets, capitalist nations were able to appease portions of the working class in their own countries.

However, Lenin still believed this system was inherently unsustainable. As monopolies grew, colonial expansion and military conquest became necessary to maintain profits. In this context, wars are not accidents or innately central to the international system, but rather a natural outcome of capitalist competition on a global scale.

For Lenin, worldwide revolution remained the ultimate goal, especially since the bourgeoisie was now a global class exploiting the proletariat across borders. However, he also believed that the revolution could begin in a single country — like Russia — and then spread. This is why he focused on consolidating power within the USSR first.

Lenin was extremely popular in some respects and deeply unpopular in others. Certain policies, like redistributing land to peasants, transferring control of factories to workers, and withdrawing Russia from World War I, gained him significant support. His personal demeanor also contributed to his appeal; he was seen as principled and committed to revolutionary ideals, rather than power-hungry. However, it would be misleading to portray Lenin’s leadership as purely democratic or benign. His rule was, in many ways, dictatorial. He launched the “Red Terror”, a campaign of violent repression against political opponents. Under his leadership, censorship was widespread, secret police (the Cheka) were established, and one-party rule dominated the Soviet state.

— Leon Trotsky Start —

It would be shameful for a blog post on the history of communism to exclude Leon Trotsky. Trotsky, a fellow revolutionary, played a crucial role in the October Revolution alongside Lenin. While the two shared many views, they differed in one important respect: Lenin wanted to consolidate power within the USSR prior to expanding the movement globally, while Trotsky believed the revolution needed to be immediately expanded worldwide in order to defeat capitalism on a global scale. (The idea that revolution could not succeed in one country alone would later be known as “permanent revolution.”)

Trotsky served as Commissar of War and led the Red Army during the Russian Civil War; he was essential to the survival of the new Bolshevik state. Despite their later disagreements, Trotsky agreed with Lenin on many foundational points — specifically the need for a vanguard party to guide the working class. He also supported harsh measures, including the suppression of counterrevolutionaries and press censorship, especially during the Civil War period.

— Leon Trotsky End —

Back to Lenin: Lenin’s time in power was relatively short. After suffering his first stroke in 1922, his health rapidly declined, and he died in 1924; his death triggered a fierce struggle for leadership amongst the Bolsheviks. His successor was Joseph Stalin, a man Lenin himself had sharply criticized in his final writings.

Joseph Stalin (Mid 1900s)

Joseph Stalin (1878–1953) rose to lead the USSR largely because of his position as General Secretary. When Lenin died in 1924, Stalin outmaneuvered his rivals — most notably Leon Trotsky — by building alliances within the party and controlling key appointments. This allowed him to shape the bureaucracy in ways that strengthened his own position.

The main ideological divide between Trotsky and Stalin was over the scope of the revolution. Trotsky, explained earlier, embraced permanent revolution, believing socialism could only survive through a worldwide uprising. Stalin took the opposite approach. Partially in line with Lenin’s pragmatism, Stalin promoted “Socialism in One Country”, focusing on consolidating socialism within the USSR before attempting to spread it abroad.

— Socialism Start —

Like the word communism, socialism is often used casually. So, what does it mean? Marx and Engels describe socialism as a transitional stage between capitalism and communism. Under socialism, the working class controls the state and uses the state to manage production and mediate certain divisions of labor. However, socialism was never the end goal. For Marx and Engels, the ultimate aim is communism, a classless society in which the state has withered away entirely.

— Socialism End —

Back to Stalin: Stalin did not abolish the idea of the vanguard party (the Communist Party remained the vanguard in name); but in practice, he centralized all authority around himself. His leadership became highly dictatorial: political debate was suppressed, dissenters were imprisoned or executed, and millions suffered through famine, repression, and state violence. Under Stalin, the USSR became a rigid authoritarian state.

Unfortunately, Stalin came to view Trotsky as one of his greatest enemies. In 1929, Trotsky was exiled from the Soviet Union. Even in exile, he remained an outspoken critic of Stalin, warning about his authoritarian tendencies. As a result, the term “Trotskyite” became a pejorative label for anyone accused of trying to infiltrate or undermine the Communist Party. This was tragic, as Trotsky was genuinely committed to the liberation of the working class and to a society free from greed and power hungry individuals. Stalin eventually ordered Trotsky’s assassination. In 1940, Soviet agent Ramón Mercader located Trotsky in Mexico and struck him with an ice axe; Trotsky died the next day. Despite his fate, Trotsky remains an important figure in history — someone who fought to uphold the revolutionary ideals set out in The Communist Manifesto.

Sidenote on the term “Marxism-Leninism”: Stalin was among the first to popularize the term Marxism–Leninism, pairing the ideas of Marx with those of Lenin. In the USSR, Marxism–Leninism became the official state ideology, grounded in Marx’s historical materialism — the belief that societies advance through successive stages of development — and Lenin’s insistence on the central, guiding role of the communist party in political life. This approach combined Lenin’s concept of a disciplined, necessary party with the ultimate goals outlined by Marx and Engels. Under Stalin — marked by suppression of dissent and widespread famine — it is difficult to argue that the regime embodied the communist ideals it claimed to uphold.

At any rate, Stalin died in 1953 from a stroke that left him partially paralyzed. After four days in a coma, he was gone. For some, his death meant the loss of a powerful leader; for many others, it marked the end of decades of tyrannical rule.

Mao Zedong (Mid to Late 1900s)

Mao Zedong (1893–1976) was the founder of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). To understand Mao’s place in the history of communism, it’s important to see how the rise of communism in China shaped his rule. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) was founded in 1921, inspired in part by the 1917 Russian Revolution led by Lenin. Mao joined the CCP shortly after the CCP was established.

In the 1920s, the CCP entered into an alliance with the Nationalist Party, or Kuomintang (KMT), in what became known as the First United Front. The two parties — despite their ideological differences — shared a goal of defeating the warlords who controlled much of China after the collapse of the Qing Dynasty in 1911. These warlords were regional military leaders who ruled territories by force.

By the late 1920s, tensions between the CCP and KMT intensified. In 1927, KMT leader Chiang Kai-shek turned on the communists in what became known as the Shanghai Massacre: thousands of communists were killed and the CCP was forces underground. The KMT aimed to unify China under a centralized, nationalist government, backed by wealthy landowners and foreign business interests — positions that the CCP opposed. As a result, Mao escaped to the countryside, where he began building support among the rural peasantry. Unlike the traditional Marxist model, which centered on industrial workers, Mao developed a strategy rooted in a peasant-based revolution.

In 1934–1935, facing destruction from KMT forces, Mao led the Long March — a year-long military retreat of the CCP’s Red Army to a new base in northwest China. Around 80,000–100,000 soldiers set out on the 6,000-mile journey across hostile terrain; they were constantly harassed by enemy attacks. By the end, only 8,000–9,000 survived. Along the way, the CCP spread propaganda, recruited new members, and forged alliances. There was no doubt that Mao was the newfound leader of the CCP. Ultimately, the CCP emerged victorious in 1949, triumphing in the civil war against the KMT. The same year, Mao founded the PRC.

Though Mao began with revolutionary ambitions, his rule — like that of Lenin and Stalin — was ultimately dictatorial. The People’s Republic of China was a one-party state where no opposition was permitted. Mao cultivated a powerful cult of personality, and those who criticized him were imprisoned, executed, or exiled. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, his campaigns led to the deaths of hundreds of thousands suspected of being anti-communist. Intellectuals were purged — either killed or sent to re-education camps.

One of Mao’s most prominent policies was the collectivization of agriculture, which abolished private farming. At the same time, he sought to rapidly industrialize China, pulling millions of peasants from the fields to work on industrial projects. This left fewer people to grow food, and combined with unrealistic production quotas, local officials inflated harvest numbers to avoid punishment. The result was the deaths of millions: the state took too much grain, leaving rural communities with little to eat and contributing to a famine that killed millions.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Mao launched the Cultural Revolution, mobilizing radicalized youth known as the Red Guards to attack perceived enemies of the regime. The movement led to the persecution of millions — many imprisoned or killed.

By the mid-1970s, Mao died after his health had seriously declined. For some, Mao’s death was a tragedy; for others, it was a sigh of relief. Though modern-day China differs greatly from Mao’s era, the state still identifies as Marxist-Leninist, claiming that its ultimate goal remains communism. The question, however, is whether this reflects genuine ideological commitment — or is this merely a façade?

Cold War Spread (1945–1979)

The history of communism doesn’t follow a perfectly straight line from Marx and Engels to Lenin, Stalin, and Mao. Around the world, other countries also embraced communism — often inspired by the leaders and revolutions we’ve already discussed. Let’s explore some of these movements now.

Eastern Europe

From 1945 to 1949, Eastern Europe fell under Soviet control in the aftermath of World War II. Communist governments were installed in countries such as Poland, Hungary, and East Germany. Most people know of the Berlin Wall which separated Soviet-controlled East Berlin from West Berlin, a NATO-aligned enclave opposed to the dictatorial Soviet government.

In 1955, the formation of the Warsaw Pact formally united these Eastern Bloc nations under a single Soviet-led military alliance. This moment became a defining event that marked the beginning of the Cold War, signaling to the West that the Eastern Bloc was firmly bound together under a shared communist framework and military.

Vietnam

Ho Chi Minh (1890–1969) is regarded as the founder of modern Vietnam. As a Marxist-Leninist, Ho was inspired by the Russian Revolution and Lenin’s writings. To understand Ho’s rise, it’s important to note that Vietnam had been under French colonial rule since the 19th century.

Ho spent years abroad, working with socialist and communist movements in China and the Soviet Union. By 1930, he helped establish the Indochinese Communist Party. When World War II ended, Ho declared Vietnam’s independence from France in 1945, famously quoting the U.S. Declaration of Independence in his speech. However, the French refused to leave the region, leading to the First Indochina War. The decisive turning point came in 1954 at the Battle of Dien Bien Phu, where, with support from the Soviet Union and Mao’s China, Ho’s forces defeated the French.

However, this did not result in communism. The United States, fearing the spread of communism under its Cold War containment policy, backed an anti-communist regime in South Vietnam. U.S. involvement escalated into the Vietnam War (1955–1975), a devastating conflict in which millions of Vietnamese and over 58,000 U.S. soldiers died. When Vietnamese civilians fled to Cambodia, the U.S. secretly bombed Cambodian territory; President Richard Nixon denied this publicly and lied to the American people.

The war ended in 1975 with the Fall of Saigon, when North Vietnamese forces captured the South Vietnamese capital. Vietnam was finally reunified. Ho, however, never saw this victory. He died from heart failure in 1969 after years of poor health.

While celebrated as a revolutionary leader, Ho’s rule shared similarities with Lenin, Stalin, and Mao. He maintained one-party control, suppressed dissent, and oversaw the execution of thousands deemed “class enemies.”

Cuba

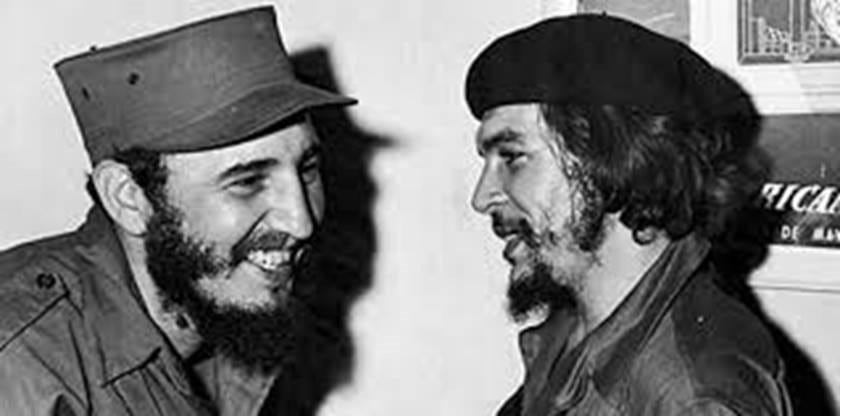

Fidel Castro (1926–2016) and Ernesto “Che” Guevara (1928–1967) are two of the most prominent figures in Cuba’s communist history. Castro overthrew the U.S.-backed dictator Fulgencio Batista in 1959. During Batista’s rule — initially from 1940 to 1944 as an elected president, and later from 1952 to 1959 as a military dictator — economic inequality deepened. U.S. corporations controlled much of Cuba’s land, key industries, and infrastructure. While elites in Havana enjoyed wealth, much of the population lived in poverty.

Alongside Castro was Guevara, an Argentine Marxist revolutionary. His travels across Latin America exposed him to widespread poverty and U.S. intervention, fueling his radicalization. Combining Guevara’s Marxist vision with Castro’s military strategy, the 26th of July Movement waged a guerrilla campaign that ultimately overthrew Batista in January 1959.

At first, Castro avoided openly declaring his government communist to prevent immediate U.S. intervention. However, in 1961, he formally proclaimed Cuba a socialist state aligned with the Soviet Union. His government quickly nationalized industries, implemented land reform, and introduced social programs — while also consolidating political power into a one-party state. Dissent was harshly suppressed: opponents were imprisoned, executed, or forced into exile.

That same year, the U.S. backed the failed Bay of Pigs Invasion, where Cuban exiles attempted to overthrow Castro. Tensions escalated further during the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, when the Soviet Union placed nuclear missiles in Cuba in response to U.S. missiles in Turkey.

Castro remained in power until illness forced him to hand over leadership to his brother, Raúl Castro, in 2008. He died in 2016, leaving behind a Cuba that had defined itself as a Marxist–Leninist state for decades. Guevara, meanwhile, left Cuba to promote revolution abroad, fighting in both the Congo and Bolivia. In 1967, he was captured and executed by CIA-backed Bolivian forces.

Decline of Communism (Late 1900s)

At the end of the Cold War, one winner remained: capitalism. The failure of communism can be traced to several events.

First was the collapse of Sino-Soviet relations. In the 1960s, China and the Soviet Union were both “communist” but disagreed over foreign policy. The Soviets saw Mao as dangerously radical, while Mao accused the Soviets of betraying revolutionary ideals by cozying up to the West. Two of the world’s largest communist powers became rivals.

Second came reforms that allowed capitalism to seep in. In China, Deng Xiaoping — Mao’s successor — introduced market-oriented reforms in the late 1970s, opening the economy to private business while still claiming to be socialist. In the Soviet Union, Mikhail Gorbachev’s economic reforms from 1985 to 1991, accelerated the USSR’s collapse.

Third was the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. This was a symbolic breach in the Soviet sphere of influence. Peaceful revolutions across Eastern Europe toppled communist governments one after another, marking the rapid decline of Soviet dominance.

Fourth the USSR dissolving itself in 1991. Nationalist movements swept through its republics — most decisively in Ukraine, whose overwhelming vote for independence signaled the USSR’s end. Fifteen new independent countries emerged from the ashes of the Soviet Union, leaving the United States as the world’s sole superpower.

Oh… Why the hammer and sickle?

The hammer and sickle are iconic symbols of communism. The hammer represents industrial workers in factories, while the sickle represents agricultural workers in the rural peasantry. After the Russian Revolution, Lenin sought a symbol to represent the alliance between these two major classes. The symbol was first designed in 1918; it was officially adopted by the Soviet Union in 1922.

The hammer and sickle remain one of the most recognizable symbols of communism. But it also raises difficult questions. Is this truly a cause worth fighting for? Or does it inevitably end in dictatorship?

Looking back at history, no nation has fully embodied the classless, stateless society envisioned by Marx and Engels. Every so-called “communist” state has retained some form of hierarchy, repression, or state. So the question remains: given what you’ve read, would you call yourself a communist?

Leave a Reply