A sentence-by-sentence reading

Structuralism. It is a term most of us have heard, but what does it really mean? In philosophical discussions, words often get tossed around casually, detached from their true meaning. And with the emergence of the term “post-structuralism,” it is only natural that confusion arises, making clarification necessary.

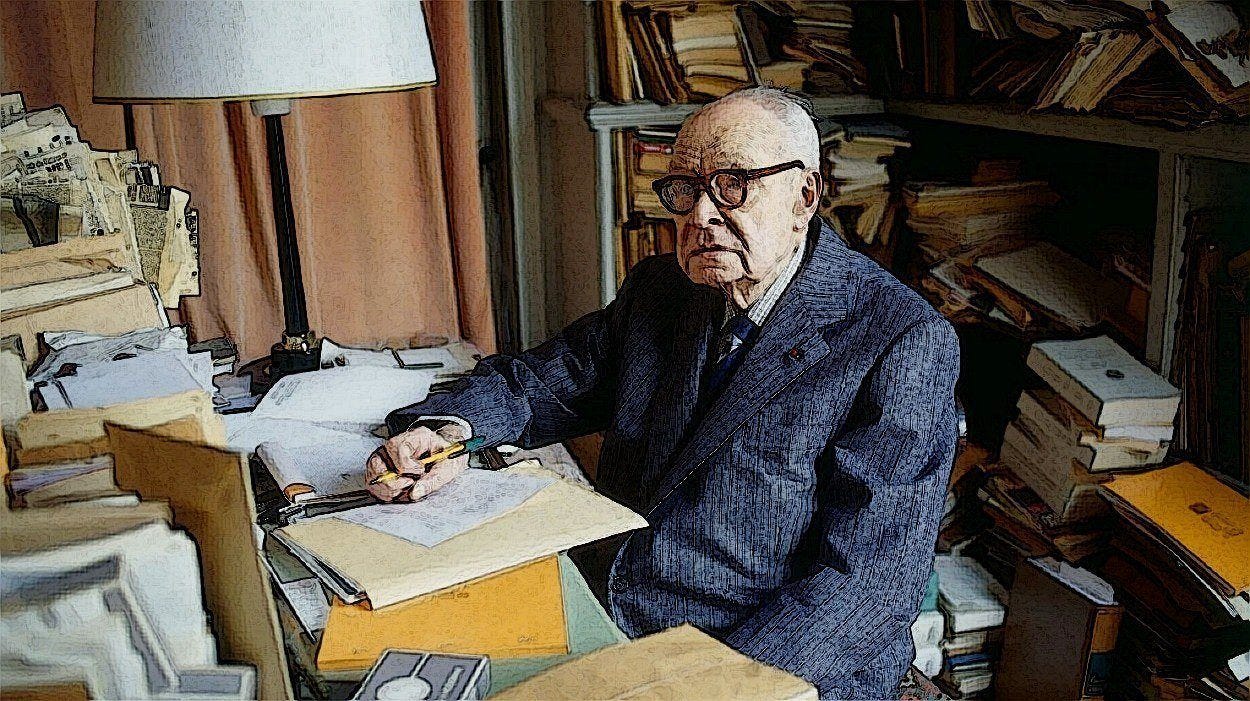

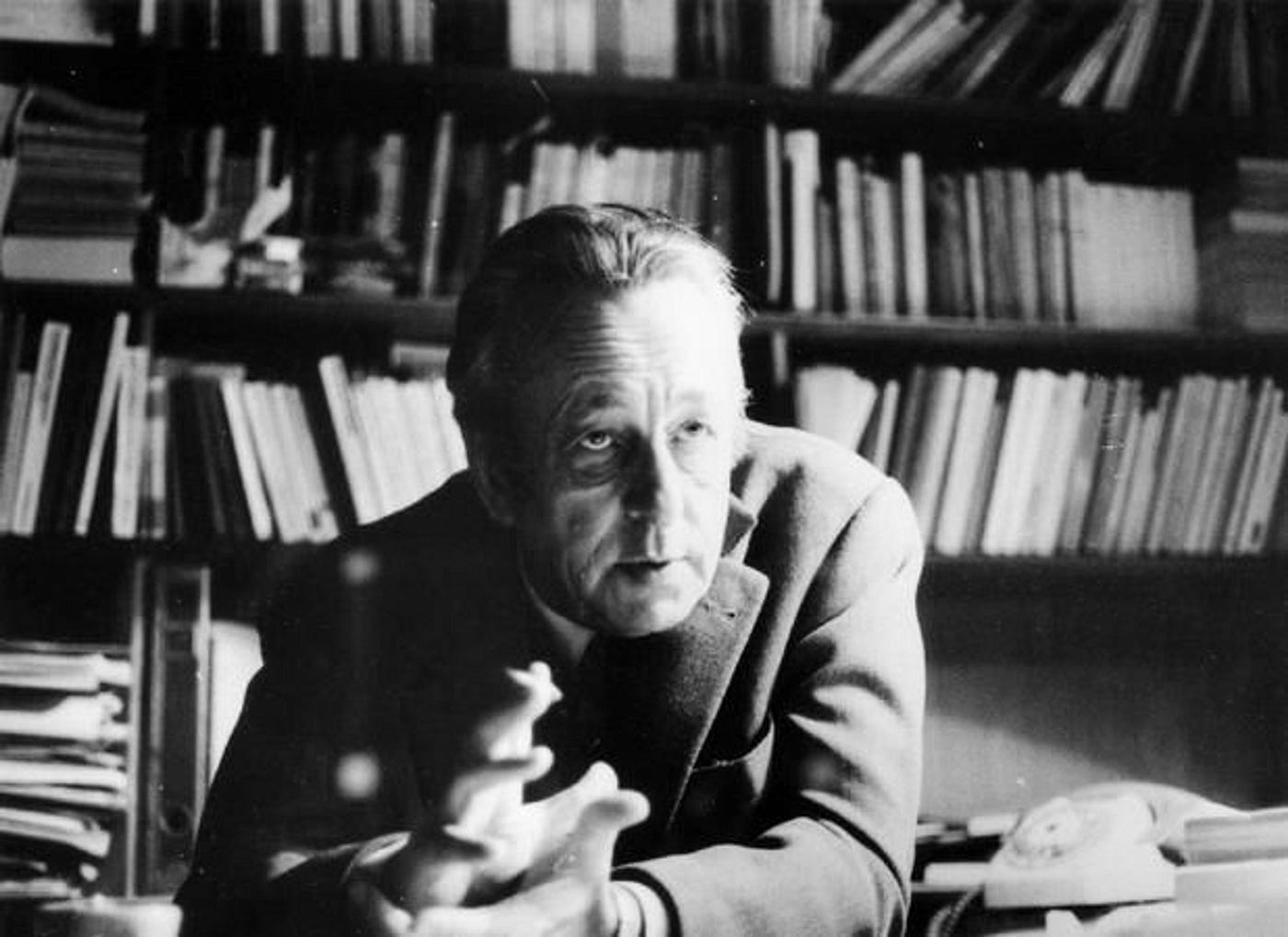

Thankfully, in 1967, Deleuze set out to define structuralism. In his essay How do we recognize structuralism? Deleuze begins by recalling a common question that was once frequently asked:

Not long ago we used to ask: What is existentialism?

Now we ask: What is structuralism?

These questions are of keen interest, provided they are timely and have some bearing on work actually in progress.

This is 1967.

Deleuze is correct to highlight that the question of what structuralism is marks a new era (at least during his time). In the earlier part of the 20th century, existentialism was gaining prominence. Philosophers like Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus, despite their differences and tensions, shared a common label: they were both considered existentialists, prompting many to ask what that actually meant. This blog post will not dive into the complexities of existentialism, but it serves to illustrate how new terms emerge as thought evolves over time. Nonetheless, Deleuze writes:

Thus we cannot invoke the unfinished character of such work to avoid a reply, for it is that character alone which gives the question its significance.

So, the question What is structuralism? must undergo certain transformations.

In the first place, who is a structuralist?

Thus, Deleuze begins his exploration by identifying several individuals who were labeled structuralists at the time of his writing:

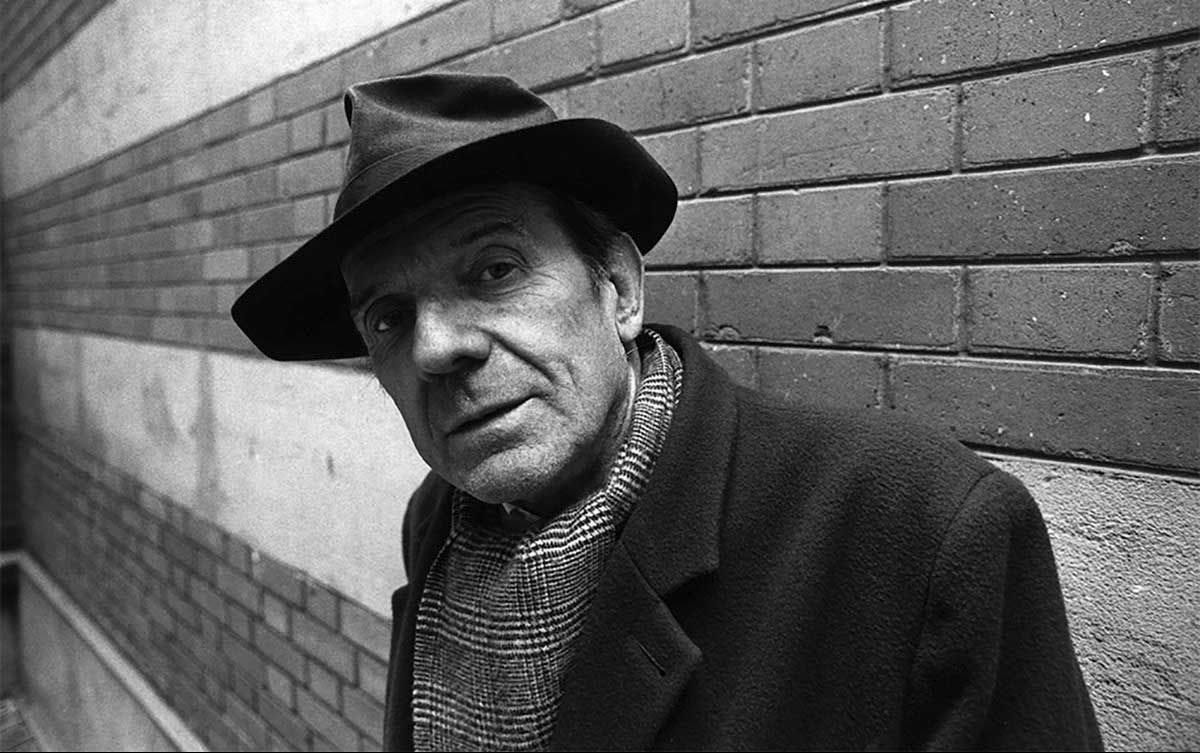

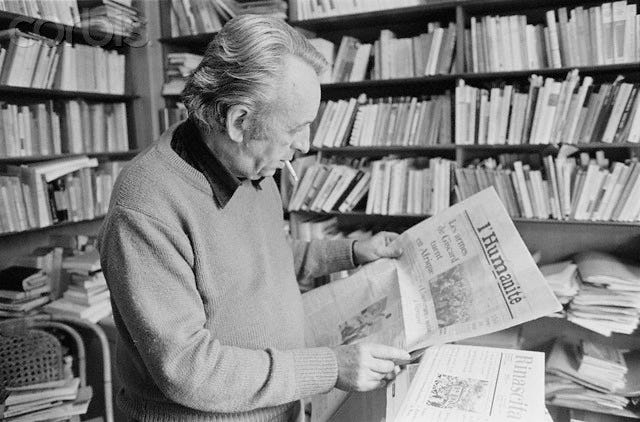

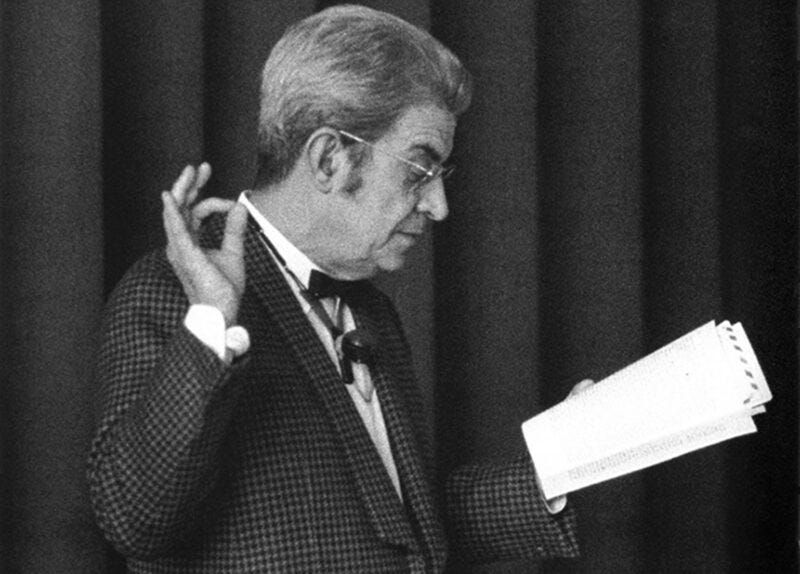

In the current climate, rightly or wrongly, it is custom- ary to name names [designer], to provide ‘samples’ [echantillonner]: a linguist like Roman Jakobson; a sociologist like Claude Levi-Strauss; a psychoanalyst like Jacques Lacan; a philosopher like Michel Foucault, renewing epistemology; a Marxist philosopher like Louis Althusser, once again taking up the problem of the interpretation of Marxism; a literary critic like Roland Barthes; writers like those from Tel Quel…

Interestingly, this list includes individuals from all kinds of disciplines and thought. In fact, Deleuze himself states:

Of these, some do not reject the word “structuralism,” and use “structure,” “structural.” Others prefer the Saussurean term “system.”

These are all very different kinds of thinkers, and from different generations, and some have exercised a real influence on their contemporaries.

However, the significance of these individuals’ works is not the central focus here. Deleuze writes:

But more import is the extreme diversity of the domains they explore. Each of them discovers problems, methods, solutions that are analogically related, as if sharing in a free atmosphere or spirit of the time, but one that distributes itself into singular creations and discoveries in each of these domains. Ism words, in this sense, are perfectly justified.

Deleuze identifies individuals who explore a wide array of fields, demonstrating how the term “structuralism” can be applied to “an extreme diversity of domains.” From linguistics and sociology to epistemology, Marxism, and even literary studies, structuralism proves to be a versatile concept, capable of application across various disciplines.

Deleuze continues by attributing the origin of structuralism to linguistics — with both Ferdinand de Saussure and the Moscow and Prague schools. He explains:

There is good reason to ascribe the origin of structuralism to linguistics: not only Saussure, but the Moscow and Prague schools.

And if structuralism then migrates to other domains, this occurs without it being a question of analogy, nor merely in order to establish methods “equivalent” to those that first succeeded for the analysis of language.

In fact, language is the only thing that can properly be said to have structure, be it an esoteric or even nonverbal language.

Although Deleuze emphasizes that language is the only system that can truly be said to have structure, he clarifies that the spread of structuralism to other disciplines is not just a straightforward application of linguistic methods via analogy. It is not about copying a method used in linguistics and applying it to other areas. Instead, as structuralism moves into other domains, it necessitates the discovery of a language that exists in each domain. Deleuze explains:

There is a structure of the unconscious only to the extent that the unconscious speaks and is language.

There is a structure of bodies only to the extent that bodies are supposed to speak with a language which is one of the symptoms.

Even things possess a structure only in so far as they maintain a silent discourse, which is the language of signs.

Deleuze makes a direct reference to psychoanalysis when he describes the unconscious as a language. Later in the essay, Deleuze identifies the French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan as a structuralist, crediting him with discovering a code to the unconscious. Though the origins of structuralism reside in linguistics, it is evident that language can be uncovered in other disciplines.

In the quote above, we find that even bodies have a structure — not because of their anatomical form, but because they “speak” a kind of language. This language, as Deleuze states, is a symptom of the body, indicating that he is not only referring to verbal expression. Rather, behaviors like nervous ticks and repetitive gestures are a kind of language of their own. These bodily expressions, for psychoanalysis, are read as signs — as symptoms of something deeper or a reflection of the unconscious. Thus, Deleuze argues that everything has a structure, insofar as everything maintains a silent discourse.

Deleuze writes:

So the question What is structuralism? is further transformed — it is better to ask:

What do we recognize in those that we call structuralists? And what do they themselves recognize? — since one does not recognize people, in a visible manner, except by the invisible and imperceptible things they themselves recognize in their own way.

How do the structuralists go about recognizing a language in something, the language proper to a domain?

What do they discover in this domain?

By redirecting the question from ‘What is structuralism?’ to ‘What do we recognize within structuralism?’, Deleuze emphasizes that the proper examination of structuralism requires identifying how language is recognized and operates within particular domains. He writes:

We thus propose only to discern certain formal criteria of recognition, the simplest ones, by invoking in each case the example of cited authors, whatever the diversity of their works and projects.

Therefore, Deleuze isolates seven criteria of structuralism, which will now be discussed.

I. First Criterion: The Symbolic

Deleuze begins the description of the first criterion of structuralism by stating:

We are used to, almost conditioned to a certain distinction or correlation between the real and the imaginary.

All of our thought maintains a dialectical play between these two notions.

Even when classical philosophy speaks of pure intelligence or understanding, it is still a matter of a faculty defined by its aptitude to grasp the depths of the real (le reel en son fond), the real “in truth,” the real as such, in opposition to, but also in relation to the power of imagination.

Ranging from classical philosophy to psychology and art, Deleuze notes that we have become conditioned to conceptualize the world via a juxtaposition between the real and the imaginary. In simple terms, the real is understood as objective reality while the imaginary is concerned with internal representations (such as unconscious drives, dreams, fantasies, and so on). The dualistic nature between the real and the imaginary has trapped us into a reductive framework: real vs. imaginary, truth vs. illusion. Deleuze writes:

Let us cite some creative movements that are quite different: Romanticism, Symbolism, Surrealism… In doing so, we invoke at once the transcendent point where the real and the imaginary interpenetrate and unite, and their sharp border, like the cutting edge of their difference.

In artistic movements such as Romanticism, Symbolism, and Surrealism, we observe a distinctive interplay between the real and the imaginary. The “transcendent point” that Deleuze highlights in these traditions refers to a space where the real and the imaginary interpenetrate and converge. Yet, despite this supposed unity between reality and fantasy, a sharp distinction between the two is always maintained.

He reiterates this point:

In any case, we get no farther than the opposition and complementarity of the imaginary and the real — at least in the traditional interpretation of Romanticism, Symbolism, etc.

Deleuze also recognizes that classical psychoanalysis falls into this trap:

Even Freudianism is interpreted from the perspective of two principles: the reality principle with its power to disappoint, the pleasure principle with its hallucinatory power of satisfaction.

With all the more reason, methods like those of Jung and Bachelard are wholly inscribed within the real and the imaginary, within the frame of their complex relations, transcendent unity and liminary tension, fusion and cutting edge.

Within Sigmund Freud’s thought, there exists both the reality principle and the pleasure principle. Even when these concepts appear to merge, there is always a distinction present between the two. Deleuze also references Carl Jung and Gaston Bachelard to emphasize this point.

With this in mind, Deleuze explains the first criterion of structuralism:

The first criterion of structuralism, however, is the discovery and recognition of a third order, a third regime: that of the symbolic.

The discovery of a third order or regime — an order that is not the real or the imaginary — is descriptive of the first criterion of structuralism. Deleuze writes:

The refusal to confuse the symbolic with the imaginary, as much as with the real, constitutes the first dimension of structuralism.

He emphasizes that the symbolic must not be conflated with either the real or the imaginary. Rather, the symbolic constitutes a distinct domain with its own structure and set of relations. Deleuze explains how, once again, the discovery of the symbolic was first found in linguistics and began to be uncovered in other domains:

In this case again, everything began with linguistics: beyond the word in its reality and its resonant parts, beyond images and concepts associated with words, the structuralist linguist discovers an element of quite another nature, a structural object.

The structural linguist, as Deleuze states, “discovers an element of quite another nature, a structural object” in the same manner as the novelists of Tel Quel, Michel Foucault, and Louis Althusser do in their respective fields:

And perhaps it is in this symbolic element that the novelists of Tel Quel wish to locate themselves, in order to renew the resonant realities as well as the associated narratives.

Beyond the history of men, and the history of ideas, Michel Foucault discovers a deeper, subterranean ground that forms the object of what he calls the archaeology of thought.

Behind real men and their real relations, behind ideologies and their imaginary relations, Louis Althusser discovers a deeper domain as object of science and of philosophy.

In the context of Lacanian psychoanalysis, Deleuze writes:

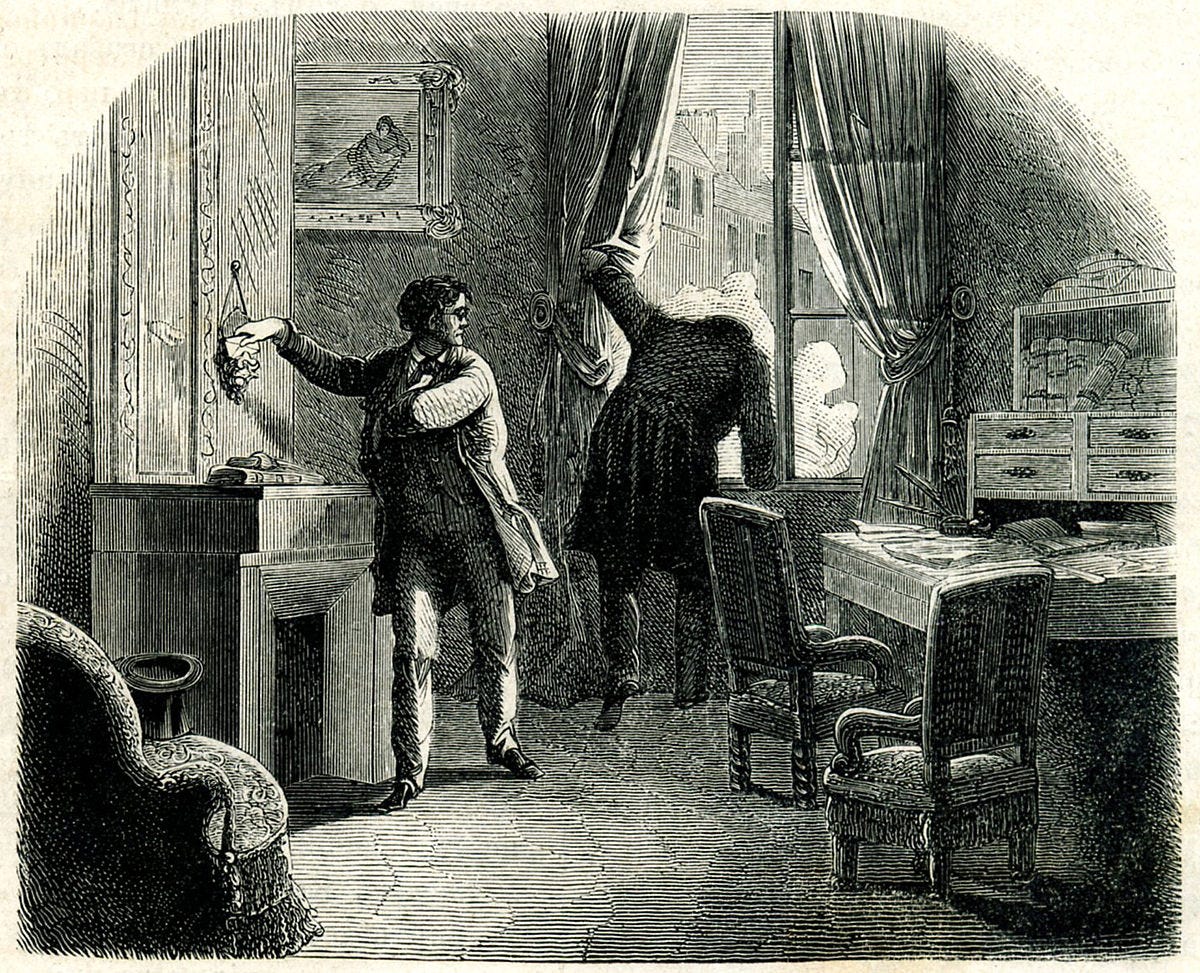

We already had many fathers in psychoanalysis: first of all, a real father, but also father-images. And all our dramas occurred in the strained relations of the real and the imaginary. Jacques Lacan discovers a third, more fundamental father, a symbolic father or Name-of-the-Father.

Deleuze credits Lacan for “discover[ing] a third, more fundamental father, a symbolic father or Name-of-the-Father.” This departure from Freudian psychoanalysis is an important one — the concept father no longer solely exists at the level of the real or the imaginary, but rather, in the symbolic, structuring signification.

Deleuze explains:

Not just the real and the imaginary, but their relations, and the disturbances of these relations, must be thought as the limit of a process in which they constitute themselves in relation to the symbolic.

The real and the imaginary should not be understood solely as independent entities, but rather through their relations to one another — relations that are intrinsically tied to a process that is fundamentally structured by the symbolic. Deleuze continues:

In Lacan’s work, in the work of other structuralists as well, the symbolic as element of the structure constitutes the principle of a genesis: structure is incarnated in realities and images according to determinable series.

Moreover, the structure constitutes series by incarnating itself, but is not derived from them since it is deeper, being the substratum both for the strata of the real and for the heights [dels] of imagination.

It is at this point that Deleuze highlights the symbolic as essential to the formation of structure. Structures are “incarnated in realities and images” through determinate sequences or series. This idea is echoed in Lacan’s Seminar on The Purloined Letter, where he identifies a specific code of the the unconscious that is structured by a chain of signifiers. Through this framework, Lacan is able to interpret the analysand’s behaviors and affective states by reading them through the symbolic order:

Conversely, catastrophes that are proper to the symbolic structural order take into account the apparent disturbances of the real and the imaginary: thus, in the case of The Wolf Man as Lacan interprets it, the theme of castration reappears in the real since it remains non-symbolized (“foreclosure”), in the hallucinatory form of the cut finger.

In the case of The Wolf Man, Lacan is able to successfully examine the symbolic order and the particular exclusions, foreclosures, and catastrophes that return to the the real in a hallucinatory form. Regardless of the specificities, the general argument is as followed: the first criterion of structuralism is the introduction of the symbolic. As Lacanian psychoanalysis emphasizes the three registers — the real, the imaginary, and the symbolic — these registers are read sequentially. Deleuze writes:

We can enumerate the real, the imaginary, and the symbolic: 1, 2, 3. But perhaps these numerals have as much an ordinal as a cardinal value.

First, we begin with the real. Deleuze finds the real to not exist outside the realm of a particular ideal or unification:

For the real in itself is not separable from a certain ideal of unification or of totalization: the real tends towards one, it is one in its “truth.” As soon as we see two in “one,” as soon as we make doubles [de’doublons], the imaginary appears in person, even if it is in the real that its action is carried out. For example, the real father is one, or wants to be according to his law; but the image of the father is always double in itself, cleaved according to a law of the dual or duel.

Second, we move to the imaginary. In the imaginary, a doubling occurs when we find two to be in “one” (the real). Though the specific action may be carried out in the real, this does not entail the absence of a doubling. In the case of the father, the real father is the one. Yet, within this one, we find a double due to imaginary identifications. Deleuze writes:

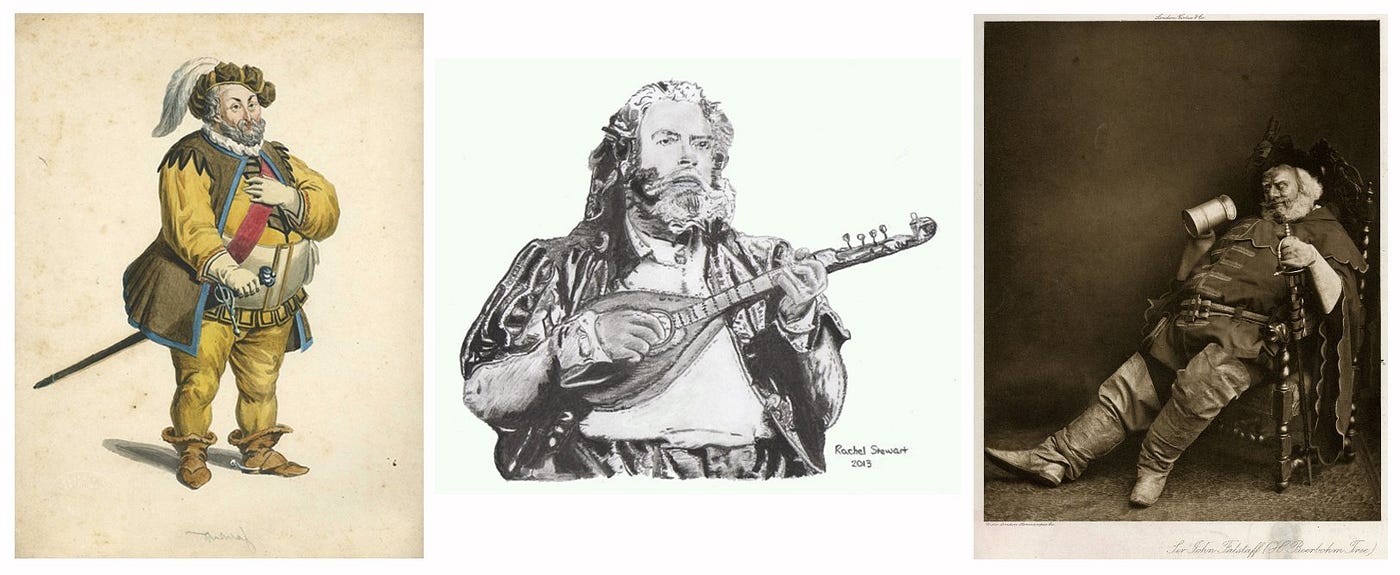

[The imaginary identification] is projected onto two persons at least, one assuming the role of the play- father, the father-buffoon, and the other, the role of the working and ideal father: like the Prince of Wales in Shakespeare, who passes from one father image to the other, from Falstaff to the Crown.

Deleuze continues by defining the Imaginary register:

The imaginary is defined by games of mirroring, of duplication, of reversed identification and projection, always in the mode of the double.

This “game of mirroring” is evident in the figure of the father: what begins as a singular, real father is soon split into two distinct images — a playful father and a strict father.

Third, we encounter the symbolic:

But perhaps, in turn, the symbolic is three, and not merely the third beyond the real and the imaginary. There is always a third to be sought in the symbolic itself; structure is at least triadic, without which it would not “circulate”— a third at once unreal, and yet not imaginable.

This is not a simple third addition to the previous two concepts. Instead, Deleuze notes that the symbolic itself has a triadic structure. As Deleuze says: “there is always a third to be sought in the symbolic itself.” He seems to be isolating how psychoanalysis focuses on the rule of three: mommy-daddy-me, ego-id-supergo.

We must remember the first criterion of structuralism:

We will see why later; but already the first criterion consists of this: the positing of a symbolic order, irreducible to the orders of the real and the imaginary, and deeper than they are.

Once again, the symbolic is not solely a third addition, but something more fundamental to the discipline it constitutes. However, the symbolic is not straight-forward either:

We do not yet know what this symbolic element consists of. We can say at least that the corresponding structure has no relationship with a sensible form, nor with a figure of the imagination, nor with an intelligible essence.

Deleuze highlights three areas that the symbolic has no relationship with — form, figure of the imaginary, and essence.

In the context of form, the symbolic has no relation to it. Deleuze writes:

It has nothing to do with a form: for structure is not at all defined by an autonomy of the whole, by a preeminence [pregnance] of the whole over its parts, by a Gestalt which would operate in the real and in perception.

Deleuze finds the symbolic to be a “structure is not at all defined by an autonomy of the whole” or a whole having prioritization over its parts. There is nothing physically tangible to the symbolic; the symbolic is content without form in the sense that it creates meaning and relationships between elements without being a concrete entity in its own right. Deleuze defines structure in the context of the symbolic:

Structure is defined, on the contrary, by the nature of certain atomic elements which claim to account both for the formation of wholes and for the variation of their parts.

It has nothing to do with figures of the imagination, although structuralism is riddled with reflections on rhetoric, metaphor and metonymy, for these figures themselves imply structural displacements which must account for both the literal and the figurative.

In the context of the figure of the imaginary, the symbolic has no relation to it. Even though structuralism is “riddled with reflections on rhetoric” and explained in terms of “metaphor and metonymy,” structure itself is not rooted in imagination. The reality is that structure defines the relations between imaginary identification.

In the context of essence, the symbolic has no relation to it. Instead, Deleuze writes:

Nor has it has anything to do with an essence:

[Structure] is more a combinatory formula supporting formal elements which by themselves have neither form, nor signification, nor representation, nor content, nor given empirical reality, nor hypothetical functional model, nor intelligibility behind appearances.

Explaining structure in terms of a “combinatory formula” highlights how structure acts as a framework that supports the combination of various elements. However, this does not indicate that structure has inherent essence or predefined meaning. Instead, structure is concerned only with the arrangement of basic units — like building blocks — that, on their own, lack form, signification, content, and so on. It is through the process of combining elements that meaning emerges. Deleuze idenfies Althusser as determining the status of the structure most effectively:

No one has better determined the status of the structure as identical to the “Theory” itself than Louis Althusser — and the symbolic must be understood as the production of the original and specific theoretical object.

To conclude this first criterion, Deleuze notes that structuralism can take on both aggressive and interpretive roles.

Sometimes structuralism is aggressive, as when it denounces the general misunderstanding of this ultimate symbolic category, beyond the imaginary and the real.

Sometimes it is interpretative, as when it renews our interpretation of works in relation to this category, and claims to discover an original point at which language is constituted, in which works elaborate themselves, and where ideas and actions are bound together.

In its aggressive mode, structuralism “denounces the general misunderstanding of this ultimate symbolic category” through a criticism. In its interpretive mode, structuralism is applied to fields and disciplines that previously lacked this framework. Furthermore:

Romanticism and Symbolism, but also Freudianism and Marxism, thus become the objects of profound reinterpretations.

Not to mention the mythical, poetic, philosophical, or practical works which themselves are subjected to structural interpretation.

But this reinterpretation only has value to the extent that it animates new works which are those of today, as if the symbolic were the source, inseparably, of living interpretation and creation.

Structuralism offers renewed interpretation of artistic movements and theoretical movements like Romanticism, Symbolism, and Surrealism and Freudian psychoanalysis.

II. Second Criterion: Local or Positional

Deleuze begins to explain the second criterion by clarifying that we must first conceptualize what structuralism is not:

What does the symbolic element of the structure consist of? We sense the need to go slowly, to state repeatedly, first of all, what it is not.

Deleuze reiterates from the previous section:

Distinct from the real and the imaginary, the symbolic cannot be defined either by pre-existing realities to which it would refer and which it would designate, or by the imaginary or conceptual contents which it would implicate, and which would give it a signification.

The symbolic cannot be categorized within the realm of the real or the imaginary as it is its own register. Nor can it be defined by something that pre-exists it or a kind of imaginary identification. Therefore:

The elements of a structure have neither extrinsic designation, nor intrinsic signification.

Then what is left?

Yet, if the elements of a structure are not defined by a register external to them, nor do they have some kind of pre-existing reality or essence, Deleuze begs the question: Then what is left? Thankfully, Deleuze answers the question by drawing from French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss:

As Levi-Strauss recalls rigorously, they have nothing other than a sense [sens = meaning and direction]: a sense which is necessarily and uniquely “positional.”

This answer is largely intuitive given that elements in a system are defined by their relation to each other. Though, what must be noted is that the positional relations that elements have in relation to one another does not exist within a “real spatial expanse” but rather of “places and sites in a properly structural space, that is, a topological space.” As Deleuze writes:

It is not a matter of a location in a real spatial expanse, nor of sites in imaginary extensions, but rather of places and sites in a properly structural space, that is, a topological space. Space is what is structural, but an unextended, pre-extensive space, pure spatium constituted bit by bit as an order of proximity, in which the notion of proximity first of all has precisely an ordinal sense and not a signification in extension.

To illustrate this idea, Deleuze gives an analogy:

Or take genetic biology: the genes are part of a structure to the extent that they are inseparable from “loci,” sites capable of changing their relation within the chromosome.

To sum up this second criterion succinctly, Deleuze states:

In short, places in a purely structural space are primary in relation to the things and real beings which come to occupy them, primary also in relation to the always somewhat imaginary roles and events which necessarily appear when they are occupied.

The example of genetics illustrates that the significance of genes lies not in their physical existence, but their position within a larger structure. As Deleuze writes:

The scientific ambition of structuralism is not quantitative, but topological and relational, a principal that Levi-Strauss constantly reaffirms.

Structuralism has a scientific ambition in the sense that it aims to be systematic and rigorous. However, this ambition is not quantitative — it does not focus on measuring elements in numerical or spatial terms. Instead, structuralism analyzes elements topologically and relationally, meaning it examines their positions and relationships relative to one another within a structure.

At this juncture, Deleuze applies this principle to Althusser and Foucault:

And when Althusser speaks of economic structure, he specifies that the true “subjects” there are not those who come to occupy the places, i.e. concrete individuals or real human beings — no more than the true objects are the roles that they fulfill and the events that are produced.

Rather, these “subjects” are above all the places in a topological and structural space defined by relations of production.

When Foucault defines determinations such as death, desire, work, or play, he does not consider them as dimensions of empirical human existence, but above all as the qualifications of places and positions which will render those who come to occupy them mortal and dying, or desiring, or workman-like, or playful.

These, however, only come to occupy the places and positions secondarily, fulfilling their roles according to an order of proximity that is an order of the structure itself.

That is why Foucault can propose a new distribution of the empirical and the transcendental, the latter finding itself defined by an order of places independently of those who occupy them empirically

What is most noticeable is how Deleuze relates structuralism to the transcendental; the structure presupposes the condition for experience itself:

Structuralism cannot be separated from a new transcendental philosophy, in which the sites prevail over whatever occupies them.

Without going into too much depth regarding transcendentalism, what is important to note is the role of sites within a structure. Deleuze writes:

Father, mother, etc., are first of all sites in a structure; and if we are mortal, it is by moving into the line, by coming to a particular site, marked in the structure following this topological order of proximities (even when we do so ahead of our turn).

Deleuze describes positions like “father” or “mother” as structural sites — places within a system that subjects can come to occupy. A subject may take up the role of ‘father’ within this structure, but this does not mean they are a father in the literal or biological sense. Rather, this subject inhabits a symbolic position defined by its relational function. To know what a father is, we must know that a father is not a mother, not a child, and so on.

Deleuze continues by citing Lacan:

“It is not only the subject,” says Lacan, “but subjects grasped in their inter- subjectivity, who line up… and who model their very being on the moment of the signifying chain which traverses them… The displacement of the signifier determines subjects in their acts, in their destiny, in their refusals, in their blindnesses, in their conquests and in their fate, their innate gifts and social acquisition notwithstanding, without regard for character or sex…”

This quote is directly from Lacan’s Seminar on The Purloined Letter where he explains the symbolic in great detail. Lacan explains that, in the context of the symbolic order, we are not dealing with an individual subject, but rather an “intersubjective modulus” with each individual occupying a site in the signifying chain. In the context of Lacan’s seminar, (the purloined letter acts as a pure signifier that moves throughout the signifying chain). The placement of this signifier (it might be appropriate to say “displacement”) “determines subjects in their acts.” Deleuze continues by praising Lacan for his discovery:

One could not say more clearly that empirical psychology is not only founded, but determined by a transcendental topology.

This reference to Lacan’s Seminar on The Purloined Letter is not the first or last time Deleuze references the seminar. You can find my blog post on Lacan’s seminar here.

Furthermore, Deleuze posits three consequences to this local or positional development that designates the second criterion:

Several consequences follow from this local or positional criterion.

Let’s review these consequences now:

The first consequence is concerned with sense (meaning). In a bit of an awkward sentence, Deleuze writes:

First of all, if the symbolic elements have no extrinsic designation nor intrinsic signification, but only a positional sense, it follows necessarily and by rights that sense always results from the combination of elements which are not themselves signifying?

Meaning emerges from the relational positions of elements within a structure, rather than being imposed externally or contained intrinsically within elements themselves. To clarify this first consequence, Deleuze writes:

As Levi-Strauss says in his discussion with Paul Ricoeur, sense is always a result, an effect: not merely an effect like a product, but an optical effect, a language effect, a positional effect.

It is evident that sense is not a product — something produced by a system. But rather, it is an inevitable effect, constantly emerging as elements change their positions within a structure. Deleuze writes:

There is, profoundly, a nonsense of sense, from which sense itself results. Not that we return in this way to what was once called a philosophy of the absurd since, for such a philosophy, sense itself is lacking, essentially.

Deleuze calls this notion of meaning being an effect “nonsense of sense” as sense is an effect of elements within a structure and not independent in its own right. Deleuze writes:

For structuralism, on the other hand, there is always too much sense, an overproduction, an over-determination of sense, always produced in excess by the combination of places in the structure. (Hence the importance, in Althusser’s work for example, of the concept of over-determination.)

However, he makes clear that this does not indicate absurdism as this kind of nonsenese:

Nonsense is not at all the absurd or the opposite of sense, but rather that which gives value to sense and produces it by circulating in the structure. Structuralism owes nothing to Albert Camus, but much to Lewis Carroll.

This clarification emphasizes that Albert Camus’ existentialist theory of the absurd does not align with structuralist thought. Nonsense is not opposed to sense; rather, it gives sense its value by crafting circulation within a structure, granting meaning a fluidity.

The second consequence is concerned with theatrics. Deleuze writes:

The second consequence is structuralism’s inclination for certain games and a certain kind of theatre, for certain play and theatrical spaces.

As Deleuze observes, structuralist theories are often closely linked to games. He gives examples of structuralist thinkers who utilize games to describe their thought:

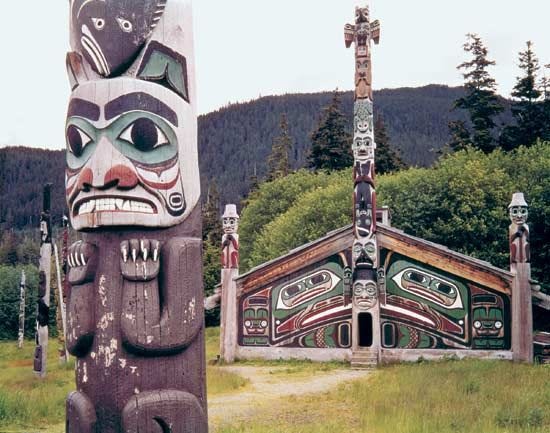

It is no accident that Levi-Strauss often refers to the theory of games, and accords such importance to playing cards.

As does Lacan to his game metaphors which are more than metaphors: not only the moving object [lefuret, literally the ferret; or, moving token in the jeu de furet, the game of hunt-the-slipper] which darts around the structure, but also the dummy-hand [la place du mort] that circulates in bridge.

The examples of Levi-Strauss and Lacan exemplify the use of games in depicting structuralist thought. Without going into detail regarding the specificities of how these thinkers utilize games, Deleuze continues by giving an example of a game relating to structuralist thought:

The noblest games such as chess are those that organize a combinatory system of places in a pure spatium infinitely deeper than the real extension of the chessboard and the imaginary extension of each piece.

Or when Althusser interrupts his commentary on Marx to talk about theatre, but a theatre that is neither of reality nor of ideas, a pure theatre of places and positions, the principle of which he sees in Brecht, and that would today perhaps find its most extreme expression in Armand Gatti’s work.

Chess is a wonderful example of how structuralism engages with games. When conceptualizing the symbolic in relation to chess, we find that meaning arises from the position of pieces on the board. The real may be understood as the material reality of the game — the physical board and pieces. The imaginary involves the identifications and images projected onto the pieces: the queen is powerful, the king is weak, and so on. The symbolic constitutes the underlying structure — there are rules and codes that give the game meaning. We must remember that this meaning is not innate but rather understood in relation to elements that are in relation to another: a gridded board, pawns placed in certain squares, etc. It is the symbolic that makes the concepts of winning/losing possible.

Deleuze concludes this second consequence by stating:

In short, the very manifesto of structuralism must be sought in the famous formula, eminently poetic and theatrical: to think is to cast a throw of the dice [penser, c’est e’met- tre un coup de des].

The third consequence is concerned with departing from the old:

The third consequence is that structuralism is inseparable from a new materialism, a new atheism, a new anti-humanism.

Deleuze speaks of structuralism introduction a deviation from older schools of thought dealing with materialism, atheism, and humanism. For Deleuze, material existence, notion of transcendence and immance, and subjectivity are all implicated by structuralism. Structuralism offers a new manner in which we are able to examine these concepts. He writes:

For if the place is primary in relation to whatever occupies it, it certainly will not do to replace God with man in order to change the structure.

Place and position is prioritized within structuralism. Whatever comes to occupy these places is important, with meaning being contingent upon the relations of these elements, but place itself is what structuralism examines. In the context of God, Deleuze notes the impossibility of changing the structure by replacing God with man. To position man at the center, instead of God, fails to recognize that there is no centrality for the structuralist. Furthermore:

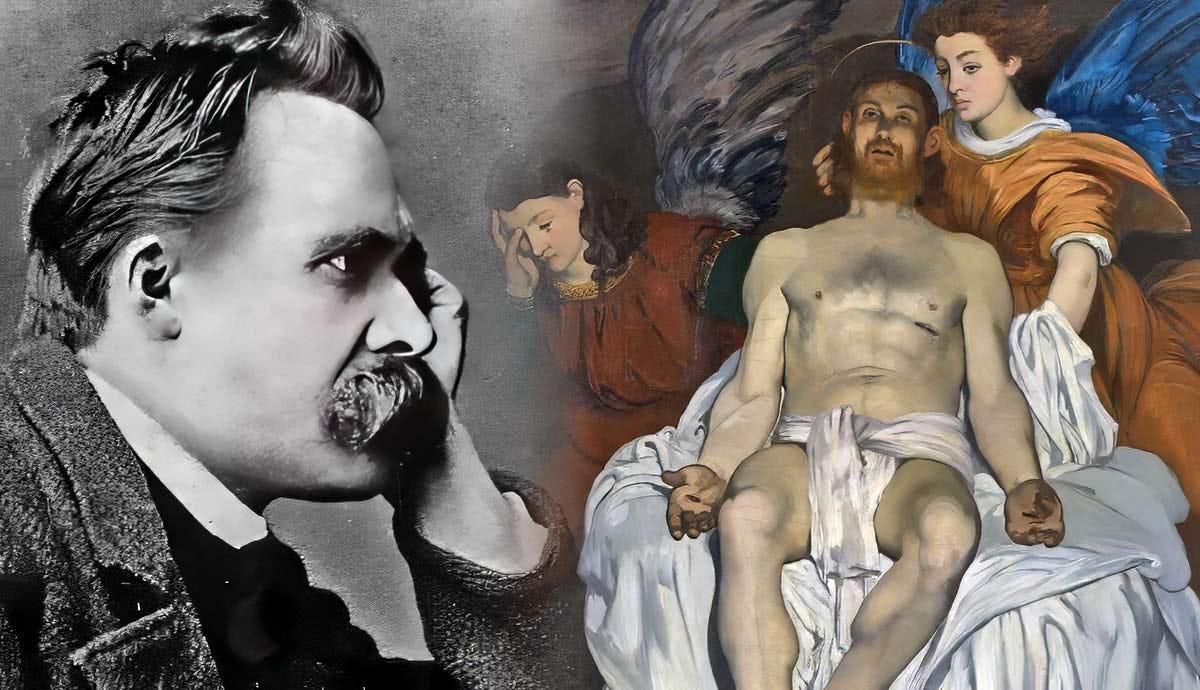

And if this place is the dummy-hand [la place du mort, i.e. the dead man’s place], the death of God surely means the death of man as well, in favor, we hope, of something yet to come, but which could only come within the structure and through its mutation. This is how we understand the imaginary character of man for Foucault or the ideological character of humanism for Althusser.

The reference to the “dead man’s place” refers to a card game that continues even if a player is physically absent — though their cards tend to stay on the table. (This might happen if someone uses the restroom quickly or grabs a snack.) The game continues because of the position — this highlights how the placement of man in God’s place does not change the structure. When Friedrich Nietzsche states that “God is dead,” the structuralist surely responds with “so is man.” Therefore, a new kind of subjectivity must arise. As Deleuze noted above, structuralism cannot be divorced from a new anti-humanism.

Deleuze concludes this third consequence by noting Foucault’s discovery. That is, Foucault’s conceptualization as man emerging via relation elements within structures that produce it.

III. Third Criterion: The Differential and the Singular

When examining the third criterion of structuralism, Deleuze begins by returning to the linguistic model:

What then do these symbolic elements or units of position finally consist of? Let us return to the linguistic model.

What is distinct both from the voiced elements, and the associated concepts and images, is called a phoneme, the smallest linguistic unit capable of differentiating two words of diverse meanings: for example, “Millard” [billiard] and “/>illard” [pillager].

A phoneme is the smallest unit of sound that differentiates words. In the example above, the word “Millard” contrasts with another word that has a letter in front of “-illard” — such as “pillager” in certain interpretations. More straightforward examples include the words “bat” and “pat,” where the phonemes /b/ and /p/ create their difference. Deleuze emphasizes that phonemes are distinct from “voiced elements,” meaning that they are not solely random sounds nor are they tied to a specific image or concept. Phonemes are the fundamental units of language that make differences possible. Deleuze notes:

It is clear that the phoneme is embodied in letters, syllables and sounds, but that it is not reducible to them.

Moreover, letters, syllables and sounds give it an independence, whereas in itself, the phoneme is inseparable from the phonemic relation which unites it to other phonemes: b / p.

Phonemes do not exist independently of the relations into which they enter and through which they reciprocally determine each other.

Once again, the phoneme cannot be reduced simply to a sound or concept — even though we express phonemes through specific sounds and written characters we call letters. What is importance is that each phoneme exists within a “phonemic relation.” This means that the function of each phoneme emerges only in relation to other phonemes. In terms of this relation, Deleuze states:

We can distinguish three types of relation.

Let us review these three types of relation now:

“A first type is established between elements which enjoy independence or autonomy: for example, 3 + 2, or even 2 / 3. The elements are real, and these relations must themselves be said to be real.”

This first type of relation is a real relation. There are independent elements that have determined and specific values.

“A second type of relationship, for example, x2 + y2 — R2 = 0, is established between terms for which the value is not specified, but which in each case, how- ever, must have a determined value. Such relations can be called imaginary.”

The second type of relation is an imaginary relation. Unlike real relations, where elements have determined, actual values, the elements in imaginary relations are undetermined in themselves. In the example x² + y² — R² = 0, x, y, and R do not have fixed values by themselves, but the structure of the equation requires that they each take on a determined value in a given instance. These terms are not defined by their relation to one another, but by their arrangement within the equation. For example, if x changes, y changes as a consequence — not due to a reciprocal determination with x, but because of how the equation as a whole constrains possible values.

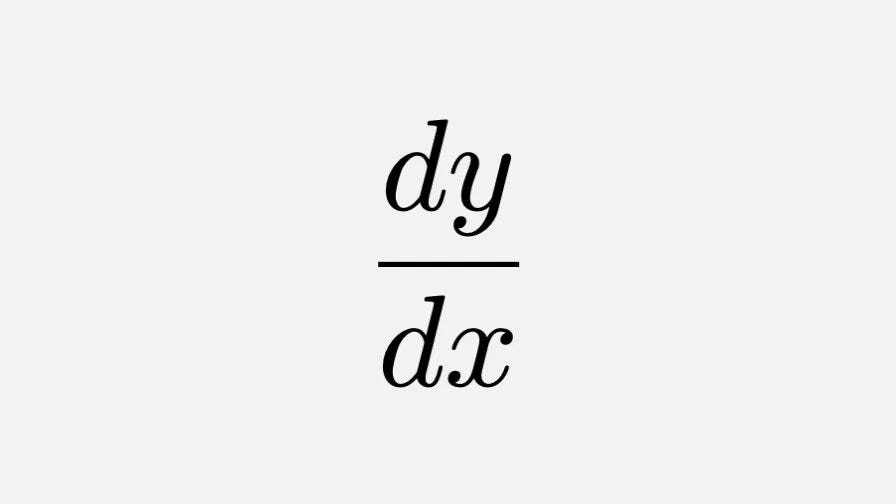

“But the third type is established between elements which have no determined value themselves, and which nevertheless determine each other reciprocally in the relation: thus ydy + xdx = 0, or dy-/ dx = — x/y. Such relationships are symbolic, and the corresponding elements are held in a differential relationship. Dy is totally undetermined in relation to y, and dx is totally undetermined in relation to x: each one has neither existence, nor value, nor signification. And yet the relation dy/dx is totally determined, the two elements determining each other reciprocally in the relation.”

The third type of relation is a symbolic relation. Unlike real and imaginary relations, symbolic relations involve elements that have no independent value or existence on their own. Instead, they are defined purely through their reciprocal determination within the relation itself. Deleuze illustrates this with differential calculus: elements like dx and dy do not have independent existence, value, or signification by themselves. Yet, in the relation dy/dx, each is determined only through the other, and the relationship itself is fully determined. Deleuze writes:

This process of a reciprocal determination is at the heart of a relationship that allows one to define the symbolic nature.

When these elements are defined reciprocally, we can properly define this relationship as a symbolic one.

To continue:

Sometimes the origins of structuralism are sought in the area of axiomatics, and it is true that Bourbaki, for example, uses the word “structure.” But this use, it seems to me, is in a very different sense, that of relations between non-specified elements, not even qualitatively specified, whereas in structuralism, elements specify each other reciprocally in relations. In this sense, axiomatics would still be imaginary, not symbolic properly speaking.

Deleuze clarifies that the field of axiomatics — particularly developed by Nicolas Bourbaki, the collective pseudonym for a group of French mathematics — is not to be confused with structuralism. Although the term “structure” appears in Bourbaki’s work, it signifies something different than what Deleuze’s analysis of structuralism. He explains:

The mathematical origin of structuralism must be sought rather in the domain of differential calculus, specifically in the interpretation which Weierstrass and Russell gave to it, a static and ordinal interpretation, which definitively liberates calculus from all reference to the infinitely small, and integrates it into a pure logic of relations.

The mathematical origin of structuralism, Deleuze argues must be located in the domain of differential calculus — not in axiomatics. He points to the work of German mathematician Karl Weierstrass and the British logician Bertrand Russell, whose interpretation of calculus departs from references to the infinitesimal and instead integrates it into a “pure logic of relations.”

Deleuze continues:

Corresponding to the determination of differential relations are singularities, distributions of singular points which characterize curves or figures (a triangle for example has three singular points).

When we examine “the determination of differential relations,” we find elements being defined only through their relation to other elements. What corresponds to this process are singularities — points that stand out and give shape to a structure. Singularities emerge from the “distribution of singular points,” that characterize a figure. For example, a triangle is composed of three points, each of which is a singularity. In calculus, when dealing with curves, inflection points function similarly as they are singularities. Furthermore:

In this way, the determination of phonemic relations proper to a given language ascribes singularities in proximity to which the vocalizations and significations of the language are constituted.

Deleuze discusses language in terms of “phonemic relations,” where meaning is produced through phonemes — irreducible units of speech that are defined only in relation to one another. These phonemic elements do not possess intrinsic meaning on their own but acquire significance through their differential relations. However, in the context of singularities, we are examining the distribution of points that characterize how language is manifested. From my understanding, these singularities refer to inflection, tone, etc. Singularities are not the phonemes themselves but the terms by which phonemes are characterized by.

Deleuze continues by reiterating the main point of this third criterion:

The reciprocal determination of symbolic elements continues henceforth into the complete determination of singular points that constitute a space corresponding to these elements.

Symbolic elements are defined in reciprocal relation to one another, and corresponding to these elements is a distribution of singular points. These singularities are mapped out in a space that give shape to a structure. Deleuze writes:

The crucial notion of singularity, taken literally, seems to belong to all the domains in which there is structure. The general formula, “to think is to cast a throw of the dice,” itself refers to the singularities represented by the sharply outlined points on the dice.

When we examine singularities in a literal sense, we find concrete points that define any domain with structure. The reference to the throw of the dice comes from French poet Stéphane Mallarmé. For Deleuze, thinking is like casting dice: while the throw is open to chance, its result is structured by the arrangement of the dots — the singular points — that determine the outcome.

Deleuze defines what structures are composed of:

Every structure presents the following two aspects: a system of differential relations according to which the symbolic elements determine themselves reciprocally, and a system of singularities corresponding to these relations and tracing the space of the structure.

Every structure is a multiplicity.

The question, “Is there structure in any domain whatsoever?,” must be specified in the following way: in a given domain, can one uncover symbolic elements, differential relations and singular points which are proper to it?

The first aspect of a structure is a “system of differential relations,” where elements are defined in relation to one another. The second aspect is a “system of singularities,” which trace the space of the structure itself. On this basis, Deleuze argues that “every structure is a multiplicity.” Though Deleuze continues to identify structuralism as the discipline of uncovering symbolic elements within a given domain, what is particularly interesting is Deleuze’s comment on symbolic elements:

Symbolic elements are incarnated in the real beings and objects of the domain considered; the differential relations are actualized in real relations between these beings; the singularities are so many places in the structure, which distributes the imaginary attitudes or roles of the beings or objects that come to occupy them.

Deleuze emphasizes that these symbolic elements are incarnated in real beings and objects. That is to say, these abstract elements to not exist as mere fantasies; they are materially embodied in the world. The differential relations — the ways in which elements are defined in relation to one another — are actualized in interactions between real beings. The singularities are also incarnated as real points within a structure as they are distributed as different positions. When a subject occupies a specific position, they then take on an imaginary attitude; this implies that a subject is not pre-determined by themselves, but they are determined by the position they occupy.

Deleuze continues:

It is not a matter of mathematical metaphors. In each domain, one must find elements, relationships and points

He moves beyond mathematics and discusses the field of anthropology with Levi-Strauss’ work, specifically within kinship structures:

When Levi-Strauss undertakes the study of elementary kinship structures, he not only considers the real fathers in a society, nor only the father-images that run through the myths of that society. He claims to discover real kinship phonemes, that is, kin-emes [parentemes], positional units which do not exist independently of the differential relations into which they enter and that determine each other reciprocally. It is in this way that the four relations — brother / sister, husband / wife, father / son, maternal uncle / sister’s son — form the simplest structure.

Similar to the math metaphors defining the relations between numbers, we find “kinship phonemes” in anthropology where familial relations such as brother/sister and husband/wife serve as simple structures — and these terms can only be understood in relation to one another (i.e., the role of the brother exists because it contrasts with sister). Deleuze continues:

And to this combinatory system of “kinship names” correspond in a complex way, but without resembling them, the “kinship attitudes” that realize the singularities determined in the system.

The “kinship names” refer to structural positions (such as brother, sister, etc.), while the “kinship attitudes” describes the roles that subjects embody when occupying these positions. Deleuze makes a subtle but important point here: singularities are only realized through their actualization via attitudes — often mediated by the imaginary. To put simply, a singularity can only be understood when it is actualized.

As our anthropological examination began with symbolic elements, Deleuze notes another approach:

One could just as well proceed in the opposite manner: start from singularities in order to determine the differential relations between ultimate symbolic elements.

Levi-Strauss uses this approach when analyzing the myth of Oedipus:

Thus, taking the example of the Oedipus myth, Levi-Strauss starts from the singularities of the story (Oedipus marries his mother, kills his father, immolates the Sphinx, is named club-foot, etc.) in order to infer from them the differential relations between “mythemes” which are determined reciprocally (overestimation of kinship relations, underestimation of kinship relations, negation of aboriginality, persistence of aboriginality).

The singularities of the Oedipus myth — such as Oedipus marrying his mother and killing his father — can be a starting point that leads one to conceptualize the symbolic elements of the domain. Levi-Strauss utilizes this strategy and calls the elements “mythemes,” or relations that define kinship and aboriginality. Deleuze states:

In any case, the symbolic elements and their rela- tions always determine the nature of the beings and objects which come to realize them, while the singularities form an order of positions that simultaneously determines the roles and the attitudes of these beings in so far as they occupy them.

The determination of the structure is therefore completed in a theory of attitudes which explains its functioning.

Once again, Deleuze highlights the importance of attitudes or the realization of positions that allow one to understand the singularities of a system. However, singularities are not symbolic elements:

Singularities correspond with the symbolic elements and their relations, but do not resemble them. One could say, rather, that singularities “symbolize” with them, derive from them, since every determination of differential relations entails a distribution of singular points.

Singularities correspond to symbolic elements, yet function as distinct points that contribute to shaping a structure. Deleuze gives an example to emphasize this point:

Yet, for example: the values of differential relations are incarnated in species, whereas singularities are incarnated in the organic parts corresponding to each species.

The example here distinguishes between the level of species and their parts. When examining symbolic elements through their differential relations, we see these relations manifest in species as a whole. In contrast — while corresponding to these symbolic relations — singularities refer to the localized points in these species, such as the parts that differentiate one species from another. Deleuze writes:

The former constitute variables, the latter constitute functions.

The former constitute within a structure the domain of appellations, the latter the domain of attitudes.”

Levi-Strauss insisted on this double aspect — derived, yet irreducible — of attitudes in relation to appellations.

A disciple of Lacan, Serge Leclaire, shows in another field how the symbolic elements of the unconscious necessarily refer to “libidinal movements” of the body, incarnating the singularities of the structure in such and such a place.

In this sense, every structure is psychosomatic, or rather represents a category-attitude complex.

Though variables and functions are found within every discipline — with psychoanalysis being a focus here — I find this to be easily understood in the area of mathematics. Deleuze continues by discussing Marxism:

Let us consider the interpretation of Marxism by Althusser and his collaborators: above all, the relations of production are determined as differential relations that are established, not between real men or concrete individuals, but between objects and agents which, first of all, have a symbolic value (object of production, instrument of production, labor force, immediate workers, immediate non-workers, such as they are held in relations of property and appropriation).

Unlike other interpretations of Marxism, Deleuze finds Althusser as analyzing the production process through the framework of structural positions. Roles such as “capitalist” or “worker” are not tied to concrete individuals but are defined as relational functions within a broader structure. Each position only gains meaning in relation to others — for there to be a capitalist, there must be a worker, and vice versa. Singularities correspond to this structural process:

Each mode of production is thus characterized by singularities corresponding to the values of the relations.

And if it is obvious that concrete men come to occupy the places and carry forth the elements of the structure, this happens by fulfilling the role that the structural place assigns to them (for example the “capitalist”), and by serving as supports for the structural relations.

This occurs to such an extent that “the true subjects are not these occupants and functionaries… but the definition and distribution of these places and these functions.”

The true subject is the structure itself: the differential and the singular, the differential relations and the singular points, the reciprocal determination and the complete determination.

Since singularities instantiate the structure, it is important to understand that property relations must be understood through the distribution of points. Therefore, singularities are not the positions within the structure, but the concrete points that map out and define the structure. For instance, the extraction of surplus value, the division of labor, and so on, are examples of singularities that characterize capitalism.

IV. Fourth Criterion: The Differenciator, Differentiation

Deluze begins this explanation of the fourth criterion by stating:

Structures are necessarily unconscious, by virtue of the elements, relations and points that compose them. Every structure is an infrastructure, a micro-structure. In a certain way, they are not actual.

Structures serve as the basis for what gives form to things. They are not consciously known but function as the unconscious foundation of how we know. However, structures do become actualized in specific ways:

What is actual is that in which the structure is incarnated or rather what the structure constitutes when it is incarnated. But in itself, it is neither actual nor fictional, neither real, nor possible. Jakobson poses the problem of the status of the phoneme, which is not to be confused with any actual letter, syllable or sound, no more than it is a fiction, or an associated image

Thus, structures only become concrete when they take on a specific form. They are actualized through their expression in the world. Deleuze writes:

Perhaps the word virtuality would precisely designate the mode of the structure or the object of theory, on the condition that we eliminate any vagueness about the word.

When Deleuze speaks of virtuality, he is referring to a kind of field or plane of potentiality that is not yet actualized. This means that a structure exists regardless of its actualization:

For the virtual has a reality which is proper to it, but which does not merge with any actual reality, any present or past actuality. The virtual has an ideality that is proper to it, but which does not merge with any possible image, any abstract idea.

Structures are real in themselves, regardless of whether they are ever actualized. Their reality is not reducible to past events (has happened) or future possibility (will happen). Deleuze states:

We will say of structure: real without being actual, ideal without being abstract.

This is why Levi-Strauss often presents the structure as a sort of ideal reservoir or repertoire, in which everything coexists virtually, but where the actualization is necessarily carried out according to exclusive rules, always implicating partial combinations and unconscious choices.

To discern the structure of a domain is to determine an entire virtuality of coexistence which pre-exists the beings, objects and works of this domain. Every structure is a multiplicity of virtual coexistence.

To reiterate: structures are real even though they may not appear in concrete form. Similarly, structures are ideal in how they are virtually structured, but they are not abstract, as abstraction would imply a divorce from realness. Deleuze uses an example from Althusser to depict this point:

Louis Althusser, for example, shows in this sense that the originality of Marx (his anti-Hegelianism) resides in the manner in which the social system is defined by a coexistence of elements and economic relations, without one being able to engender them successively according to the illusion of a false dialectic.

Deleuze writes:

What is it that coexists in the structure?

All the elements, the relations and relational values, all the singularities proper to the domain considered.

As stated earlier, symbolic elements (and all of their relations), along with singularities distributed and mapped out, coexist to serve as the structure. Deleuze continues:

Such a coexistence does not imply any confusion, nor any indetermination for the relationships and differential elements coexist in a completely and perfectly determined whole.

Except that this whole is not actualized as such.

What is actualized, here and now, are particular relations, relational values, and distributions of singularities; others are actualized elsewhere or at other times.

The coexistence of symbolic elements, their relations, and singularities does not imply disorder or confusion. Nor is it vague or indeterminate — the structure is fully and precisely determined. The elements and singularities exist together as a whole, though it does not require actualization of this whole. However, in a given time and place, the structure is definitively actualized. The structure may not be present all at once but this does not imply its existence as a whole. He gives an example pertaining to language:

There is no total language [langue], embodying all the possible phonemes and phonemic relations.

But the virtual totality of the language system [langage] is actualized following exclusive rules in diverse, specific languages, of which each embodies certain relationships, relational values, and singularities.

No single language — whether English, Spanish, Arabic, Chinese, and so on — contains every possible phoneme or phonemic relation. This does not entail that a total, all-encompassing language exists elsewhere nor does it imply that absence of a structure. Rather, different parts of the virtual structure of language are actualized in specific manners across individual languages. For instance, certain phonemic relations appear in Chinese that are absent in English.

Deleuze gives another example:

There is no total society, but each social form embodies certain elements, relationships, and production values (for example “capitalism”).

Akin to language, there is no single society that fully actualizes the virtual structure of society. Instead, we encounter distinct social forms — such as primitive, despotic, or capitalist societies. This does not indicate the absence of a virtual social structure, but rather that each form embodies different aspects of its actualization.

To continue:

We must therefore distinguish between the total structure of a domain as an ensemble of virtual coexistence, and the sub-structures that correspond to diverse actualizations in the domain.

Deleuze highlights the need to distinguish between the entire virtual structure and the sub-structures that actualize parts of it. The partial actualizations of this structure — such as specific languages or social forms — must not be mistaken for the entirety of the virtual structure itself. Deleuze writes:

Of the structure as virtuality, we must say that it is still undifferentiated (c), even though it is totally and completely differential (t).

When we examine a virtual structure, it is undifferentiated, meaning that it has not yet been actualized or taken concrete form. However, this structure is differential, meaning that elements can only define themselves in relation to their position within a structure. The specific entities that occupy particular positions or functions are less important than the fact that the structure consists of distinct positions and functions. Furthermore:

Of structures which are embodied in a particular actual form (present or past), we must say that they are differentiated, and that for them to be actualized is precisely to be differentiated.

Specific structures have been realized, whether in the present or past, with particular languages and social forms emerging and disappearing. These embodied structures can be called differentiated, as they take on distinct forms and are made of differentiated elements (such as phonemes in language, for example). He explains:

The structure is inseparable from this double aspect, or from this complex that one can designate under the name of differential (t) / differentiation (c), where t / c constitutes the universally determined phonemic relationship

The virtual structure can only be understood from this “double aspect”: the differential and the differentiation. The differential refers to the symbolic elements that compose a structure, while differentiation refers to the actualization of that structure.

Deleuze continues by discussing differentiation and the differential:

All differentiation, all actualization is carried out along two paths: species and parts.

The differential relations are incarnated in qualitatively distinct species, while the corresponding singularities are incarnated in the parts and extended figures which characterize each species: hence, the language species, and the parts of each one in the vicinity of the singularities of the linguistic structure; the specifically defined social modes of production and the organized parts corresponding to each one of these modes, etc.

When we examine differentiation, we find it is “carried out along two paths.” First, there is species, which refers to broad categories or structures. Second, there are parts, which are the individual components that make up these species. In terms of differential relations, these are actualized through distinct species, with the singularities tied to the parts of within each species. For instance, Deleuze uses the example of “language species,” where languages like English or Spanish serve as a species which includes different parts, such as specific languages and their phonemes. The same concept applies to social modes of production: capitalism is a species made up of parts.

Deleuze writes:

One will notice that the process of actualization always implies an internal temporality, variable according to what is actualized.

Not only does each type of social production have a global internal temporality, but its organized parts have particular rhythms.

Here, Deleuze brings up the concept of temporality to explain how actualization unfolds. Actualization is not instantaneous — it always takes place over time, and the nature of this temporality depends on what is being actualized. In the case of social production, different social systems have distinct internal temporalities; each unfolds according to its own pace. Moreover, within any given system, the organized parts — such as labor relations within the social form of capitalism — follow their own specific rhythm. For instance, labor relations follow their own rhythm compared to the internal temporality of capitalism.

As regards time, the position of structuralism is thus quite clear: time is always a time of actualization, according to which the elements of virtual coexistence are carried out at diverse rhythms.

Time goes from the virtual to the actual, that is, from structure to its actualizations, and not from one actual form to another.

Time is not solely a sequences of events — it is only understood as a process by which virtual structures become actualized; specifically, this process of actualization is accordance to the specific rhythms of each part.

Or at least time conceived as a relation of succession of two actual forms makes do with expressing abstractly the internal times of the structure or structures that are realized at different depths in these two forms, and the differential relations between these times.

Even if we conceptualize time as a successive of events or forms (primitivism → despotism → capitalism), we still have the ability to understand that different social forms are capable of being actualized. However, the internal times of a structure are realized as “different depths in these two forms” (the species and the parts) take shape. Deleuze writes:

And precisely because the structure is not actualized without being differentiated in space and time, hence without differentiating the species and the parts which carry it out, we must say in this sense that structure produces these species and these parts themselves.

It produces them as differentiated species and parts, such that one can no more oppose the genetic to the structural than time to structure.

Genesis, like time, goes from the virtual to the actual, from the structure to its actualization; the two notions of multiple internal time and static ordinal genesis are in this sense inseparable from the play of structures.

To reiterate: a structure is not actualized unless it is differentiated within space and time. This actualization relates to species and parts which the structure produces. It is impossible to separate structure from genesis in the same manner that it is impossible to separate structure from time; structuralism is not opposed to time, but rather, explain how time occurs through the actualization of structures. Genesis and time move from the the virtual to the actual.

Deleuze continues by detailing a summary of this fourth criterion:

We must insist on this differenciating role. Structure is in itself a system of elements and of differential relations, but it also differentiates the species and parts, the beings and functions in which the structure is actualized. It is differential in itself, and differentiating in its effect.

He continues by emphasizing a quote from French philosopher Jean Pouillon:

Commenting on Levi-Strauss’s work, Jean Pouillon defined the problem of structuralism: can one elaborate “a system of differences which leads neither to their simple juxtaposition, nor to their artificial erasure?”

Thus, the problem structuralism seeks to address is how to construct a system in which differences are maintained, without being flattened through assimilation or rended indistinguishable through juxtaposition. Levi-Strauss’ anthropological work, as argued by Deleuze, is structuralist by nature, but so are other disciplines:

In this regard, the work of Georges Dumezil is exemplary, even from the point of view of structuralism: no one has better analyzed the generic and specific differences between religions, and also the differences in parts and functions between the gods of a particular, single religion.

For the gods of a religion, for example, Jupiter, Mars, Quirinus, incarnate elements and differential relations, at the same time as they find their attitudes and functions in proximity to the singularities of the system or “parts of the society” considered.

French religious studies scholar Georges Dumézil is often praised by Deleuze, who also emphasizes that Dumézil holds significant importance within the framework of structuralism:

[The gods of a religion] are thus essentially differentiated by the structure which is actualized or carried out in them, and which produces them by being actualized.

It is true that each of them, considered solely in its actuality, attracts and reflects the function of the others, such that one risks no longer discovering anything of this originary differenciation which produces them from the virtual to the actual.

Without going into too much detail, all Deleuze is arguing is that Dumézil’s analysis of various gods of religion are differentiated via a structure that actualizes them. He writes:

But it is precisely here that the border passes between the imaginary and the symbolic: the imaginary tends to reflect and to resituate around each term the total effect of a wholistic mechanism, whereas the symbolic structure assures the differential of terms and the differentiation of effects.

This is a clear reference to Lacanian psychoanalysis as Deleuze is isolating the imaginary and the symbolic registers. The Imaginary is concerned with unified images whereas the symbolic is concerned with difference as elements are only given meaning in relation to one another. On this point, Deleuze notes:

Hence the hostility of structuralism toward the methods of the imaginary: Lacan’s critique of Jung, and the critique of Bachelard by proponents of “New Criticism.”

He finds structuralism to be hostile toward the “methods of the imaginary.” Deleuze mentions Lacan’s criticisms of Jung — particular Jung’s focus on the imaginary via archetypal figures — along with criticisms of Bachleard. Furthermore:

The imagination duplicates and reflects, it projects and identifies, loses itself in a play of mirrors, but the distinctions that it makes, like the assimilations that it carries out, are surface effects that hide the otherwise subtle differential mechanisms of symbolic thought.

The imagination works through duplications, reflection, and projection, meaning that it imposes an image upon something which causes it to lose itself in the process; it “loses itself in a play of mirrors” as it is akin to looking in a mirror and assuming the reflection is the real thing. Even if the imagination appears to make distinctions, it is only surface-level. Beneath this is “subtle differential mechanisms of symbolic thought.” Deleuze states:

Commenting on Dumezil, Edmond Ortigues has this to say: “When one approaches the material imagination, the differential function diminishes, one tends towards equivalences; when one approaches the formative elements of society, the differential function increases, one tends towards distinctive values [valences].”

The term “material imagination” refers to how religion and storytelling utilize images to convey a message. However, within this domain, “the differential function diminishes,” which means that distinctions between elements become blurred and deemed equivalent — images serve as substitutions that can be applied universally upon any element. For example, gods and goddesses in mythology frequently rules over many different domains, showing how the imagination tends to merge roles and meanings. In contrast, when we analyze social structures, differences are much sharper as there needs to be strict boundaries between king, queen, peasant, and so on.

Deleuze continues:

Structures are unconscious, necessarily overlaid by their products or effects.

An economic structure never exists in a pure form, but is covered over by the juridical, political and ideological relations in which it is incarnated.

One can only read, find, retrieve the structures through these effects.

The terms and relations which actualize them, the species and parts that realize them, are as much forms of interference [brouillage] as forms of expression.

Structures themselves are not experienced consciously. Rather, what is experienced is the effects of structures. Deleuze gives the example of an economic structure never existing in “pure form” but as something covered up by various effects. Further still:

This is why one of Lacan’s disciples, J.-A. Miller, develops the concept of a “metonymic causality,” or Althusser, the concept of a properly structural causality, in order to account for the very particular presence of a structure in its effects, and for the way in which it differenciates these effects, at the same time as these latter assimilate and integrate it.

Now, if it is true that structures become actualized, the question becomes how something not concrete can become concrete. Deleuze utilizes Miller “metonymic causality” and Althusser’s structural causality to properly conceptualize how structures become actualized. The structure itself does not cause effects in the sense that it is actively causing actualization. Instead, the structure organizes positions and functions. Even though the structure appears absent, it is already readily present in the way that effects are organized along with how these effects are differentiated. An interesting point that Deleuze makes it that these differentiated affects “assimilate and integrate” the structure, meaning that these effects embody the structure.

To continue:

The unconscious of the structure is a differential unconscious.

One might believe then that structuralism goes back to a pre-Freudian conception: doesn’t Freud understand the unconscious as a mode of the conflict of forces or of the opposition of desires, whereas Leibnizian metaphysics already proposed the idea of a differential unconscious of little perceptions?

But even in Freud’s writing, there is a whole problem of the origin of the unconscious, of its constitution as “language,” which goes beyond the level of desire, of associated images and relations of opposition.

In structuralist thought, the unconscious is understood as differential — composed not of repressed content, but of positions, functions, and relations within a system of differences. Deleuze posits that it is possible for structuralism to have taken root much further back than Freud, notably in the work of Gottfried Leibniz. Leibniz’s theory of the monad and his concept of “little perceptions” is emblematic of a structuralist view of the unconscious. Freud did not clearly separate between the imaginary and the symbolic, and understood the unconscious as a site of opposing desires. However, Deleuze notes that we should not dismiss Freud entirely — some of Freud’s work does suggest a kind of proto-structuralist approach to the unconscious. Deleuze writes:

Conversely, the differential unconscious is not constituted by little perceptions of the real and by passages to the limit, but rather of variations of differential relations in a symbolic system as functions of distributions of singularities.

Though he isolated Leibniz as potentially being closer to what he calls structuralism, Deleuze still finds Leibniz’s monads to not fully equate to the differential unconscious. The differential unconscious does not accumulate these “little perceptions.” Instead, it is solely understood as difference within a symbolic system. He continues:

Levi-Strauss is right to say that the unconscious is made neither of desires nor of representations, that it is “always empty,” consisting solely in the structural laws that it imposes on representations and on desires.

Once again, Deleuze draws from Levi-Strauss and argues that the unconscious is not composed of various desires nor of images or representations. The unconscious relates to form — not content — thus making it empty. It is only actualized when elements enter into specific positions and functions within this structure.

Deleuze writes:

For the unconscious is always a problem, though not in the sense that would call its existence into question.

Rather, the unconscious by itself forms the problems and questions that are resolved only to the extent that the corresponding structure is instantiated [s’effectue] and always according to the way that it is instantiated.

For a problem always gains the solution that it deserves based on the manner in which it is posed, and on the symbolic field used to pose it.

The unconscious is always a problem — but not in the sense that its existence is in doubt. Rather, the unconscious produces problems that are themselves structured symbolically and invite interpretation. However, these problems can only be resolved when a symbolic structure is actualized. The form that any solution takes depends entirely on how the problem was posed within that structure. Deleuze writes:

Althusser can present the economic structure of a society as the field of problems that the society poses for itself, that it is determined to pose for itself, and that it resolves according to its own means, that is, according to the lines of differentiation along which the structure is actualized (taking into account the absurdities, ignominies and cruelties that these “solutions” involve by reason of the structure).