“The anti-gender movement is a politically consequential form of anti-intellectualism” — Butler

American philosopher, Judith Butler, recently released their newest work: Who’s Afraid of Gender? Because I am interested in critical theory pertaining to gender, I picked up a copy of the book. After reading the 36-page introduction, I am both impressed and intrigued by Butler’s arguments. Their writing style is accessible, thought-provoking, and elegant.

What I appreciate about this book is that Butler is not presenting a theory about gender or framing the content as an academic debate. Instead, Butler is clearly examining fascism in the public sphere and its real-world impacts upon gender and sexual minorities. These impacts are, evidently, propagated by right-wing individuals who demonize and oppress those who do not conform to a supposed clear and organized gender norm.

Butler writes:

My task here is neither to provide a new theory of gender nor to defend or reconsider the performative theory that I offered nearly thirty-five years ago … I hope only to refute some falsehoods in the process and to understand how and why these falsehoods surrounding “gender” are circulating with the phatasmatic power they do. (Who’s Afraid of Gender?, 23; emphasis mine)

Introduction

Butler begins by highlighting the pervasive role gender plays in our society. From checking a box on a form or academic discussions in the classroom, gender remains a relevant and topical discussion that requires serious deliberation and examination.

Butler defines gender as a phantasm, like that of a ghost where something is present but not well-defined:

Circulating the phantasm of “gender” is also one way for existing powers — states, churches, political movements — to frighten people to come back into their ranks, to accept censorship, and to externalize their feat and hatred onto vulnerable communities. (Who’s Afraid of Gender?, 6)

Throughout the introduction, Butler explores how governmental policies (such as those in Florida), various religions (such as the Catholic Church and its upholding of the ideal form of Man), and other political entities (like the right-wing and their nonsensical slogans), shape the dialogue and rhetoric that structure gender as a type of syntax.

One thing that must be noted is that Butler’s analysis is examined through a psychoanalytical lens. In fact, when discussing gender as a “phantasm,” Butler is theorizing alongside French psychoanalyst, Jean Laplache:

In referring to a “phantasmic scene,” I adapt the theoeretical formulation of Jean Laplache, the late French psychoanalyst, for thinking about psychosocial phenomena. (Who’s Afraid of Gender?, 10)

To define gender as a “phantasm” or a “phantasmic scene,” Butler utilizes the psychoanalytic concepts of condensation and displacement. Without going into too much depth, I’ll just offer quick definitions of these concepts:

- Condensation: According to Oxford References, condensation is “the representation of several chains of mental associations by a single idea.” This is normatively understood in the context of dreams.

- Displacement: According to the American Psychological Association, displacement is “a defense mechanism in which the individual discharges tensions associated with, for example, hostility and fear by taking them out on a less threatening target.”

Butler’s argument is simple: the problems of society are condensed into a single idea and displaced onto what we call “gender.” We must not forget that gender is just an illusion of the mind — a phantasm.

Therefore, it is easy to understand that the right-wing is seeking a scapegoat for the degradation of society. Rather than focusing on how to solve the issues of global warming, economic inequality, gun violence, etc., the Right places blame on those not adhering to gender norms. To them, the structural foundation of society is falling apart because the universal notion of gender that they grasp so dearly is being questioned.

Butler writes:

Consider the allegation that “gender” — whatever it is — puts the lives of children at risk.

This is a powerful accusation.

(Who’s Afraid of Gender?, 12)

These powerful accusations, however, fail to question or critically interrogate what gender is in the first place. To sum up this “phantasmic scene”—along with the process of condensation and displacement — Butler states:

In the process of reproducing the fear of destruction, the source of destruction is externalized as “gender.” (Who’s Afraid of Gender?, 13)

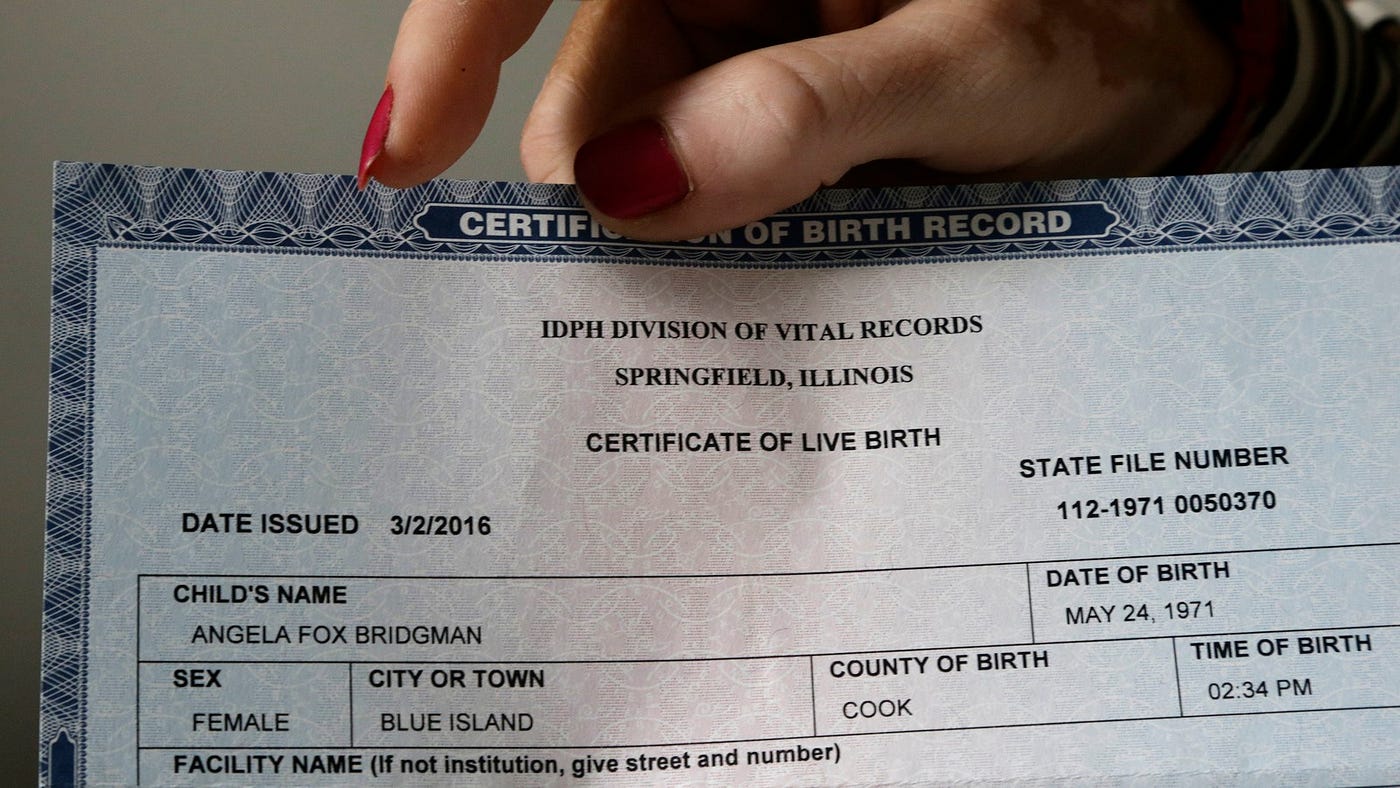

From the outset, we are assigned genders. Before birth, we are labeled with an M or an F, compelled to conform to the prevailing cultural narrative surrounding gender. Consequently, many individuals question or challenge these arbitrary norms but are met with resistance. To someone who believes in gender as a universality — a God-given norm that we must adhere to — those who challenge dominant gender tropes are wrong from the start.

Butler explicates how dissents against the norm are readily defined as “bad”:

This is why our ability to criticize ideologies is necessarily rooted in the position of a bad or broken subject: someone who has failed to approximate the norms governing individuation, putting us in the difficult position of breaking with our own upbringing or formation in order to think critically in our own way, and to think anew, but also to become someone who does not fully comply with the expectations so often communicated through sex assignment at birth. (Who’s Afraid of Gender?, 14)

At any rate, Butler continues by defining the anti-gender ideology movement as a recruitment effort where everyone in the movement invests in a “collective dream”:

Recruitment into the anti-gender ideology movement is an invitation to join a collective dream, perhaps a psychosis, that will put an end to the placable anxiety and fear that afflict so many people experiencing climate destruction firsthand, or ubiquitous violence and brutal war, expanding police powers, or intensifying economic precarity.

(Who’s Afraid of Gender?, 15)

I appreciate how Butler describes this collective dream as a “psychosis.” (This reminds me of Deleuze and Guattari’s theorization of delirium.) Here, Butler observes that the anti-gender ideology movement holds the belief that achieving a flawless gender construction within society will resolve all issues.

Yet, we must ask ourselves an essential question: What exactly is the ultimate objective of the anti-gender ideology movement? We often hear voices within this movement lamenting the failure of the new generation’s men and women. But … When in history was there ever a fixed, universal notion of man or woman? When has a generation ever been successful? Which specific era are they referring to? We must remember that the categorizations of man and woman have always been in a state of flux.

Thus, the past that the anti-gender ideology movement believes is only a fantasy. It never existed.

Butler describes this point clearly:

The idea of a past belongs to a fantasy whose syntax reorders elements of reality in the service of a driving force that renders opaque its own operation. (Who’s Afraid of Gender?, 15–16)

Butler later explains how this view is innately fascist, and prevents the expansion of fundamental freedoms:

In the name of maintaining the status quo or returning to an idealized past, fascists impugn social and political movements that seek to expand our fundamental commitments to freedom and equality.” (Who’s Afraid of Gender?, 25)

One intriguing observation by Butler concerned the contradictory nature of anti-gender ideology. They write:

“Gender represents capitalism, and gender is nothing but Marxism; gender is a libertarian construct, and gender signal the new wave of totalitarianism.” (Who’s Afraid of Gender?, 16).

So … which is it?

Or, to use another example, the Right argues against one being brain washed, and to not be a sheep, yet they curtail any form of difference in opinion regarding gender. This phantasm, oddly enough, is allowed to be contradictory as it reshapes itself for self-serving interests:

The contradictory character of the phantasm allows it to contain whatever anxiety or fear that the anti-gender ideology wishes to stoke for its own purposes, without having to make any of it cohere. (Who’s Afraid of Gender?, 16)

At first glance, it may appear that the anti-gender movement is rooted in opposition to gender. However, the reality is that the anti-gender movement is not at all opposed to gender: “They have a precise gender order in mind that they want to impose upon the world” (Who’s Afraid of Gender?, 18). At any rate, Butler’s introduction spends a lot of time explaining how the anti-gender advocates argue in bad faith. They fail to engage in any critical literature surrounding gender, yet constantly dismiss it as incorrect. Butler explains:

The anti-gender advocates are largely committed to not reading critically because they imagine that reading would expose them — or subjugate them — to a doctrine which they have, from the start, levied objections. (Who’s Afraid of Gender?, 19)

Ironically, the anti-gender movement accuses the Left of being dogmatic, all the while consuming biased media, adhering strictly to religious texts, and repeating the same contradictory and incoherent talking points over and over again. I seldom discuss personal opinions or experiences in blog posts, but based on my own encounters, I’ve found few groups as deeply entrenched in anti-intellectualism as individuals within the anti-gender movement.

In the real world, the Left is heavily engaged in intellectual debates regarding gender, constantly refining their understanding of it:

Gender studies is a diverse field marked by internal debate, several methodologies, and no single framework. (Who’s Afraid of Gender?, 19–20)

The Right, however, is “skeptical of the academy for fear that intellectual debates may well confuse them about the values they hold” (Who’s Afraid of Gender?, 21)

Unfortunately, because the Right is obsessed with a “big government for thee but not for me” mentality, they are seeking to eradicate gender studies programs, prohibit discussions about gender and sex within the classroom, and send gender and sexual minorities to conversion camps. Butler understands the gravity of this ascendance towards fascism — or rather, recognizes that we are already there — and anticipates that their book will serve as a step towards challenging it.

My hope is to show that opening up a discussion of gender to thoughtful debate will demonstrate the value of gender as a category to help us explain how, considered as a problem of embodiment in social life, gender can be the site of anxiety, pleasure, fantasy, and even terror. (Who’s Afraid of Gender?, 24)

One of my personal favorite lines:

Sex assignment is not simply an announcement of the sex that an infant is perceived to be; it also communicates a set of adult desires and expectations. (Who’s Afraid of Gender?, 30)

Leave a Reply