We must ask ourselves: “What are we doing?”

Hannah Arendt’s The Human Condition stands as a significant and influential text in Western philosophy. By delving into the essence of the human condition, Arendt navigates through various philosophical epochs and offers criticisms of Plato and Marx. This blog post seeks to examine the Prologue in The Human Condition.

**Citation Note: Full citation provided at the end of this post

Prologue

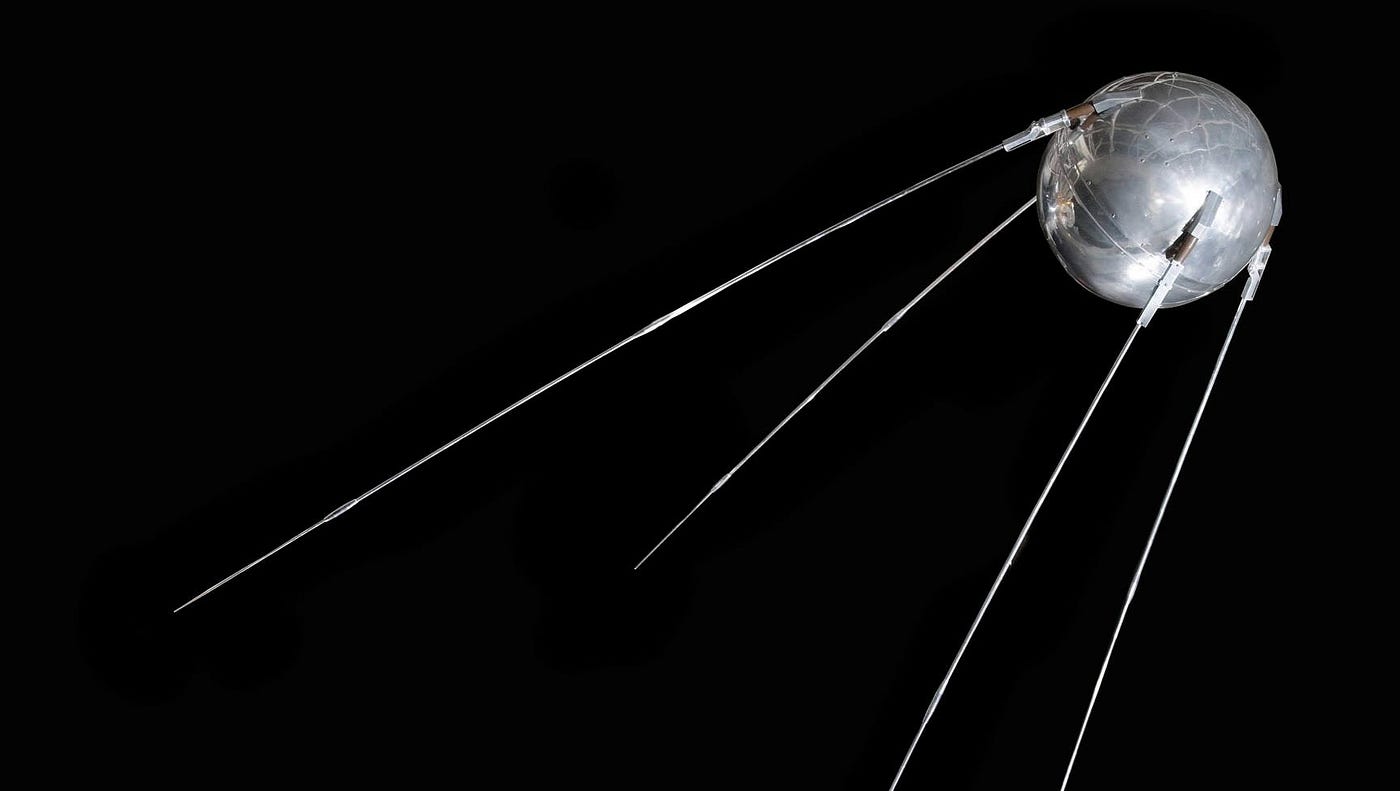

Arendt begins The Human Condition with a description of a satellite being sent into the depths of the universe:

In 1957, an earth-born object made by man was launched into the universe … the man-made satellite was no moon or star … This event, second in importance to no other, not even to the splitting of the atom, would have been greeted with unmitigated joy if it had not been for the uncomfortable military and political circumstances attending it …

Under typical circumstances, the public would perceive the launch of a satellite into space as an achievement, emblematic of human ingenuity. Yet, Arendt observes that the immediate reaction of the public was one of relief, as it was seen as the initial stride towards liberation from earthly confinement.

Arendt states:

The immediate reaction, expressed on the spur of the moment, was relief about the first “step toward escape from men’s imprisonment to the earth.”

The advancement of technological progress, through collective aspirations, have created a culture that anticipates and surpasses its own technological advancements. Arendt notes that “science has realized and affirmed what men anticipated in dreams that were neither wild nor idle.” In this way, science fiction was one discarded, but now it intersects with reality, highlighting a transformative shift in societal values. Yet, with this change in societal notions of progress, Arendt questions whether the eagerness and anticipation to escape Earth represents a departure from traditional religious and philosophical beliefs.

She writes:

For although Christians have spoken of the earth as a vale of tears and philosophers have looked upon their body as a prison of mind or soul, nobody in the history of mankind has ever conceived of the earth as a prison for men’s bodies or shown such eagerness to go literally from here to the moon.

In essence, the ultimate question centers around whether the idea of departing from Earth represents a repudiation of the Earth as the “Mother of all living creatures under the sky”, in favor of embracing technological advancement. Though many may seem quick to discard the Earth, Arendt notes that “the earth is the very quintessence of the human condition.”

What makes humans different from other living organisms?

Arendt explicates:

The human artifice of the world separates human existence from all mere animal environment, but life itself is outside this artificial world, and through life man remains related to all other living organisms.

However, scientific progress has aimed to render life increasingly artificial, seeking to sever the final connection that binds humanity to the realm of nature, as articulated by Arendt. She illustrates this with examples such as generating life in laboratories (test tube babies), manipulating germ plasm for eugenic purposes, and extending human life-spans beyond the hundred-year limit.

She continues:

This future man, whom the scientists tell us they will produce in no more than a hundred years, seems to be possessed by a rebellion against human existence …

This rebellion against human existence presents the possibility of diverging into two paths. Firstly, Arendt underscores the potential for ‘enhancing’ humanity, as demonstrated by the previous examples. Conversely, she warns of the capability to annihilate all organic life on Earth, emphasizing the critical importance of discerning the intended purpose behind the advancement of such technical knowledge. Therefore, the question of the purpose behind this scientific progress “cannot be decided by scientific means; it is a political question.”

At any rate, these technological potentials lie in a not-so-distant future, bringing forth a crisis within the natural sciences through diverse forms of innovation. While we acknowledge the mathematical proofs underpinning natural sciences, it’s crucial to question whether scientific truths can still be articulated conventionally through speech and thought. To clarify this point, Arendt elucidates a scenario where human communication and cognition become entirely reliant on machines:

In this case, it would be as though our brain, which constitutes the physical, material condition of our thoughts, were unable to follow what we do, so that from now on we would indeed need artificial machines to do our thinking and speaking.

Dependence on artificial machines for human speech and cognition results in humans becoming subordinate to machines, blurring the distinction between humans and machines. Arendt identifies a reality where humans operate and function as “thoughtless creatures at the mercy of every gadget which is technically possible, no matter how murderous it is.”

Therefore, the issue concerning the progress of science is of “great political significance.” Arendt asserts that any concern involving speech becomes inherently political, as “speech is what makes man a political being.” Should our cultural values align more closely with scientific progress, Arendt argues, we risk embracing a lifestyle where speech loses its significance.

She explains:

For the sciences today have been forced to adopt a “language” of mathematical symbols which, though it was originally meant only as an abbreviation for spoken statements, now contains statements that in no way can be translated back into speech. (emphasis mine)

Though I understand the argument that Arendt is making, I can’t recall a specific instance where certain sciences adopt mathematical symbols that cannot be translated into speech. While fields like advanced theoretical physics, quantum mechanics, or computer science can be difficult to discuss conversationally, Arendt appears to suggest an absolute impossibility of translating certain sciences into speech.

Arendt emphasizes that the basis for distrusting scientists’ political judgement does not stem from scientists’ character or their naïveté. Rather, this distrust arises from the environment in which scientists operate — “a world where speech has lost its power.” The collective human experience, for Arendt, relies on speech and communication with one another. Arendt states:

Men in the plural, that is, men in so far as they live and move and act in this world, can experience meaningfulness only because they can talk with and make sense to each other and to themselves.

Another related topic (sort of) is the advent of automation and its potential impact on society. Arendt believes that automation has the capability to “liberate man-kind [from] the burden of laboring” as a means of revolutionizing the labor force. She believes that automation do the work so that humans don’t have to. This serves as yet another rebellion against the human condition: “the wish to be liberated from labor.” Despite modern efforts to liberate ourselves from labor, specifically through technological advancements, Arendt notes that the desire to be free from labor is not a new concept. In the past, freedom from labor was present among a privileged few.

The contemporary era has brought with it the “theoretical glorification of labor” which has resulted in society being centered around labor. Evidently, the wish to be liberated from labor is akin to a fairytale and a self-defeating act. Labor, within a society of laborers, becomes the foundational fabric of society; Arendt notes that within this type of society, “there is no class left, no aristocracy of either a political or spiritual nature.” This indicates that there are no classes or groups to provide an alternative view for human activity beyond labor. Even presidents, kings, and prime ministers occupy positions that are deemed as mere jobs rather than a role with heightened significance. All of this results in an ominous view of society:

What we are confronted with is the prospect of a society of laborers without labor, that is, without the only activity left to them. Surely, nothing could be worse.

For Arendt, a society in which individuals are no longer engaged in labor, yet have structured their entire lives around it, and therefore lack meaningful activities, is deeply unsettling. In this situation, individuals are deprived of the only activity that gave them purpose in their lives.

Arendt concludes the prologue by stating that The Human Condition does nor provide answers to the concerns it raises. This is because:

Such answers are given every day, and they are matters of practical politics, subject to the agreement of many; they can never lie in theoretical considerations or the opinion of one person, as though we dealt here with problems for which only one solution is possible.

However, Arendt proposes a new way in which we ought to consider the human condition: “from the vantage point of our newest experiences and our most recent fears.” Arendt highlights the importance of contemplation and thoughtful reflection — something she finds lacking in modern society. By re-examining the human condition, Arendt finds her project to be quite simple.

She writes:

What I propose, therefore, is very simple: it is nothing more than to think what we are doing.

In describing the theme of the book, Arendt posits that the central question of the book is: “What we are doing?” She isolates that the book is going to explore the three basic activities universal to all individuals — labor, work, and action — which are explored in great detail throughout the book’s three central chapters.

Arendt finishes the Prologue by arguing that the modern age is not the same as the modern world. She explains that the modern age began in the seventeenth century and concluded at the beginning of the twentieth century. In political terms, the modern world, the world in which we live today, began with the first atomic explosions. Arendt explains that the focus of the book is not purely a historical analysis of the modern world and how it came to be; instead, the she explains that the book focuses on the human condition and how it manifests itself. At times, Arendt will focus on historical analysis in order to …

… trace the origins of modern world alienation and understand the nature of society as it existed at the moment when it was overtaken by the emergence of a new and unknown era. This historical examination aims to provide insight into the societal shifts and transformations leading up to the present moment.

Thus, she proceeds into Chapter One: Viva Activa and the Human Condition.

— —

Citation:

- Arendt, Hannah. The Human Condition. The University of Chicago Press. 1958.

Leave a Reply