“The decisive means for politics is violence”

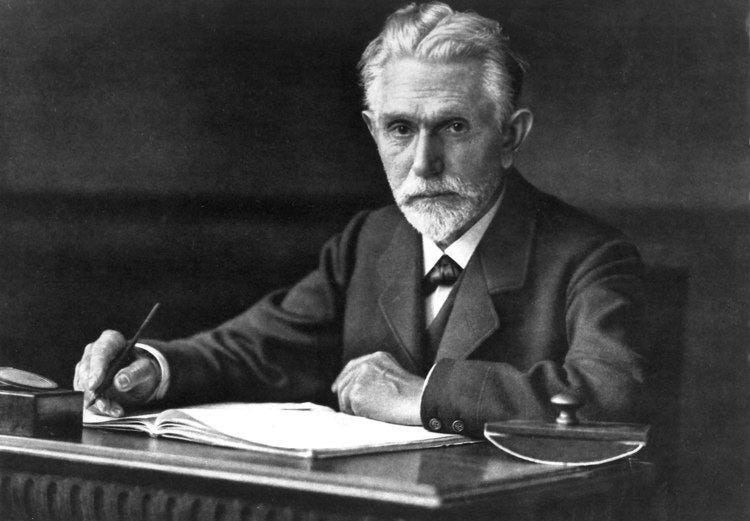

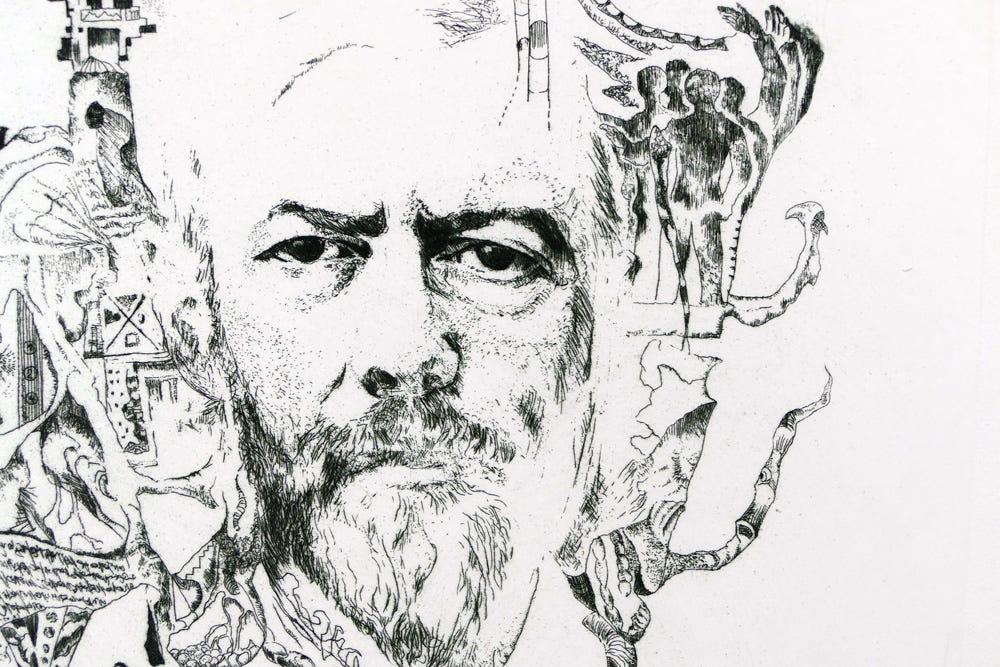

In 1919, the German sociologist and political theorist Max Weber delivered a lecture on political involvement, which was subsequently transformed into a written text. This blog will explore Weber’s Politics as a Vocation and provide an analysis of the text.

**Citation Note: Full citation provided at the end of this post

Introduction

Rather than focusing on the “issues of the day,” Weber highlights that “questions that refer to what policy and what content one should give one’s political activity must be eliminated.” The inquiries about specific public policies do not address the essence of politics as a vocation.

Weber begins by establishing that the word ‘politics’ is a very broad and ambiguous concept. For example, one may speak of the “currency policy of the banks … one may speak of the educational policy of a municipality or a township, of the policy of the president of a voluntary association …” All of these policies may serve of high importance, but the examples listed by Weber showcase the broad nature of the term ‘politics’. Instead of seeking to conceptualize politics in relation to individual public policies, Weber offers an alternative approach:

We wish to understand by politics only the leadership, or the influencing of the leadership, of a political association, hence today, of a state. (emphasis mine)

This approach should come as no surprise to political theorists: examining what the state is and how the state operationalizes serves of extreme importance. Although there have been many approaches to defining the terms that constitute the state, Weber presents a thought-provoking analysis. He acknowledges that, “sociologically, the state cannot be defined in terms of its ends.” In this manner, Weber emphasizes the necessity of exploring the intricate workings of the state rather than a focus on a state’s intended (or unintended) outcomes.

Thus, Weber concludes:

One can define the modern state sociologically only in terms of the specific means peculiar to it, as to every political association, namely, the use of physical force.

On this point, Weber cites Trotsky: ‘Every state is founded on force’

Our social institutions are predicated from the use of physical force and violence; if they weren’t, “then the concept of ‘state’ would be eliminated, and a condition would emerge that could be designated as ‘anarchy,’ in the specific sense of this word.” However, none of this is to assume that physical force is the only means of the state, “force is a means specific to the state.” With the concept of violence in mind, it is clear that the state utilizes physical force to ensure its existence, while simultaneously, determining its physical force as legitimate. Therefore, Weber offers a provocative definition of the state:

We have to say that a state is a human community that (successfully) claims the monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force within a given territory.

Weber further articulates this notion by stating: “The state is considered the sole source of the ‘right’ to use violence.” The types of violence normalized, or more accurately, legitimized by the state, vary across different states. Nevertheless, a commonality persists — the state defines and legitimizes specific forms of violence within its jurisdiction. Consequently, politics can be defined as the pursuit of “striving to share power or striving to influence the distribution of power, either among states or among groups within a state.” No individual desires to be inherently subjected to oppressive and violent forces. Hence, politics revolves around the endeavor to influence power dynamics in a way that redefines the legitimation of specific physical forces and acts of violence.”

For Weber, the state is “a relation of men dominating men, a relation supported by means of legitimate (i.e. considered to be legitimate) violence.”

Weber posits three inner justifications for the legitimization of domination:

First, the authority of the ‘eternal yesterday,’ i.e. of the mores sanctified through the unimaginably ancient recognition and habitual orientation to conform.

Regarding the first justification, there exist cultural and historical traditions sanctioned by the state, establishing a longstanding pattern of conformity. Religion serves as an immediate example, and within this context, the state mirrors religion (it is unsurprising that numerous states incorporate religion as a foundational element). This resemblance emerges from the collective belief in a higher authority, shaped by individual convictions and the inclination to adhere. Yet, one might question whether documents like the Bill of Rights or amendments in the U.S. Constitution function as a form of ‘ancient recognition’ (akin to religious texts).

[Second,] there is the authority of the extraordinary and personal gift of grace (charisma), the absolutely personal devotion and personal confidence in revelation, heroism, or other qualities of individual leadership.

Regarding the second justification, a state possesses charismatic authority, though the extend of this charisma various among states. This ‘gift of grace’ fosters a sense of comfort among individuals, leading them to willingly subject themselves to the authority of the state.. In a religious context, this charisma is embodied by the prophet. In the political realm, a comparable dynamic exists as there is the “elected war lord, the plebiscitarian ruler, the great demagogue, or the political party leader.”

[Thirdly,] there is domination by virtue of ‘legality,’ by virtue of the belief in the validity of legal statute and functional ‘competence’ based on rationally created rules.

Regarding the third justification, individuals are expected to fulfill their obligations as outlined by statutory laws. This domination is seen in the exercising of power in modern times. Weber calls individuals fulfilling their obligations as “servant[s] of the state”; each individual is expected to embody “state consciousness” so to speak (my words). Whether one is a government official, a public servant, or a regular citizen, there is an expectation that each individual follows sand upholds the rules, regulations, and legal statutes set forth by the state.

To sum up these three justifications, Weber states:

When asking for the ‘legitimations’ of this obedience, one meets with these three ‘pure’ types: ‘traditional,’ ‘charismatic,’ and ‘legal.’

Rather than focusing on all three justifications of domination, Weber is most interested in charismatic authority. “Here,” Weber says, “we are interested … in the second of these types: domination by virtue of the devotion of those who obey the purely personal ‘charisma’ of the ‘leader.’” When an individual devotes themselves to the charisma of the prophet, or in this case, the leader of the state, it means that “the leader is personally recognized as the innerly ‘called’ leader of men.” Weber explicates:

Men do not obey [the leader] by virtue of tradition or statute, but because they believe in him.

There are two aspects of charismatic leadership, with the leader embodying both aspects. “Charismatic leadership,” Weber states, “has emerged in the two figures of the magician and the prophet on the one hand, and in the elected war lord, the gang leader and condotierre on the other hand.” In a Machiavellian sense, there is a love/fear relationship a leader has with those he leads over: an individual is granted peace and highest praise when following the law, and this same individual is punished when they break the law.

Evidently, the state requires an administrative staff in its exercise of political domination:

The administrative staff [is] like any other organization, bound by obedience to the powerholder …

Two mechanisms that cater to the personal interests of administrative staff and secure their commitment to uphold and enforce the law are: “material reward[s]” and “social honor”. Rarely does anyone engage in free labor, without form of compensation; even if coerced — such labor still exacts a cost. Therefore, wages serve as a prominent example of personal interests related to material rewards for bureaucrats sanctioned by the state. On the other hand, social honor pertains to individuals exhibiting a sense of patriotism in their service to the state.

For Weber, “to maintain a dominion by force, certain material goods are required, just as with an economic organization.” The state needs resources in order to enforce its domination. In this sense, there is a clear differentiation that one is able to make between states:

All states may be classified according to whether they rest on the principle that the staff of men themselves own the administrative means, or whether the staff is ‘separated’ from these means of administration.

At this juncture, a crucial question arises: what constitutes the means of administration? Weber addresses this by assering that “the administrative means may consist of money, building, war material, vehicles, horses, or whatnot.” The central query revolves around whether the administrative staff possesses ownership of these means or if they are detached from the tools of administration. In this context, Weber provides a succinct method for distinguishing between states: he perceives states as distinct from one another based on how power is distributed within their administrative structures.

In the earliest political formations, we “find the lord himself directing the administration. He seeks to take the administration into his own hands by having men personally dependent upon him: slaves, household officials …” Yet, unlike this model, where a single individual takes control of the entire administration, modern states are increasingly characterized as “the bureaucratic state order” where they constitute a “rational development”. Weber explains:

The modern state controls the total means of political organization, which actually come together under a single head.

No single official personally owns the money he pays out, or the buildings, stores, tools, and war machines he controls.

In the contemporary ‘state’ — and this is essential for the concept of state — the ‘separation’ of the administrative staff, of the administrative officials, and of the workers from the material means of administrative organization is completed.

In concluding our definition of the modern state, Weber highlights:

The modern state is a compulsory association which organizes domination. It has been successful in seeking to monopolize the legitimate use of physical force as a means of domination within a territory

Avocation vs. Vocation

Now that we have properly defined and characterized the existence of the modern state, we must turn our attention to the role of politics in relation to the state and its legitimization of violence. Weber conceptualizes politics like that of an economic pursuit: politics may be a man’s avocation or his vocation. Here, Weber explains how individuals engage in politics:

One may engage in politics, and hence seek to influence the distribution of power within and between political structures, as an ‘occasional’ politician.

Noting the existence of the ‘occasional’ politician, Weber argues that:

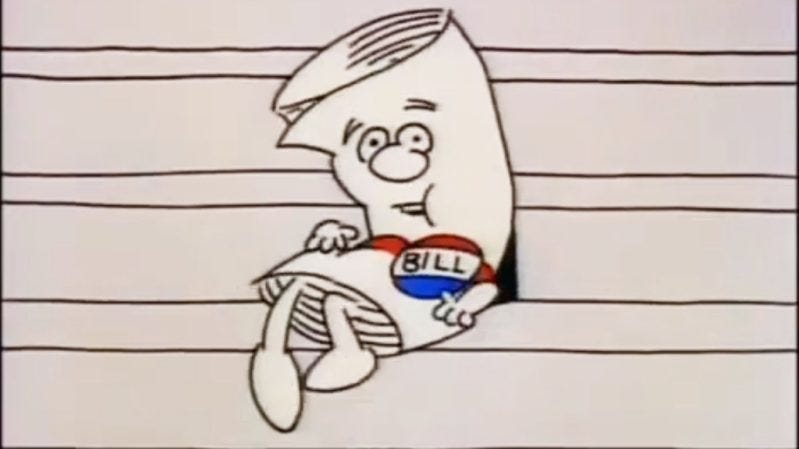

We are all ‘occasional’ politicians when we cast our ballot or consummate a similar expression of intention, such as applauding or protesting in a ‘political’ meeting, or delivering a ‘political’ speech, etc.

For most people, “the whole relation of many people to politics is restricted to [that of the ‘occasional’ politician]”. The ‘occasional’ politician views politics as an avocation — like that of a hobby or short-term occupation. Yet, there are those who make politics their vocation. To make politics one’s vocation, “either one lives ‘for’ politics or one lives ‘off’ politics”; Weber isolates that these terms are not exclusive, one can live ‘for’ and live ‘off’ politics.

What does it mean for someone to live ‘for’ politics?

He who lives ‘for’ politics makes politics his life, in an internal sense.

Either he enjoys the naked possession of the power he exerts, or he nourishes his inner balance and self-feeling by the consciousness that his life has meaning in the service of a ‘cause.’

Certainly, if one is dedicated to a particular skill or craft — in this case, politics — and is committed to improving it, it is evidence that many individuals who live ‘for’ politics sustain themselves through this commitment. However, there are also many individuals aiming to derive income for their involvement in politics:

He who strives to make politics a permanent source of income lives ‘off’ politics as a vocation, whereas he who does not do this lives ‘for’ politics.

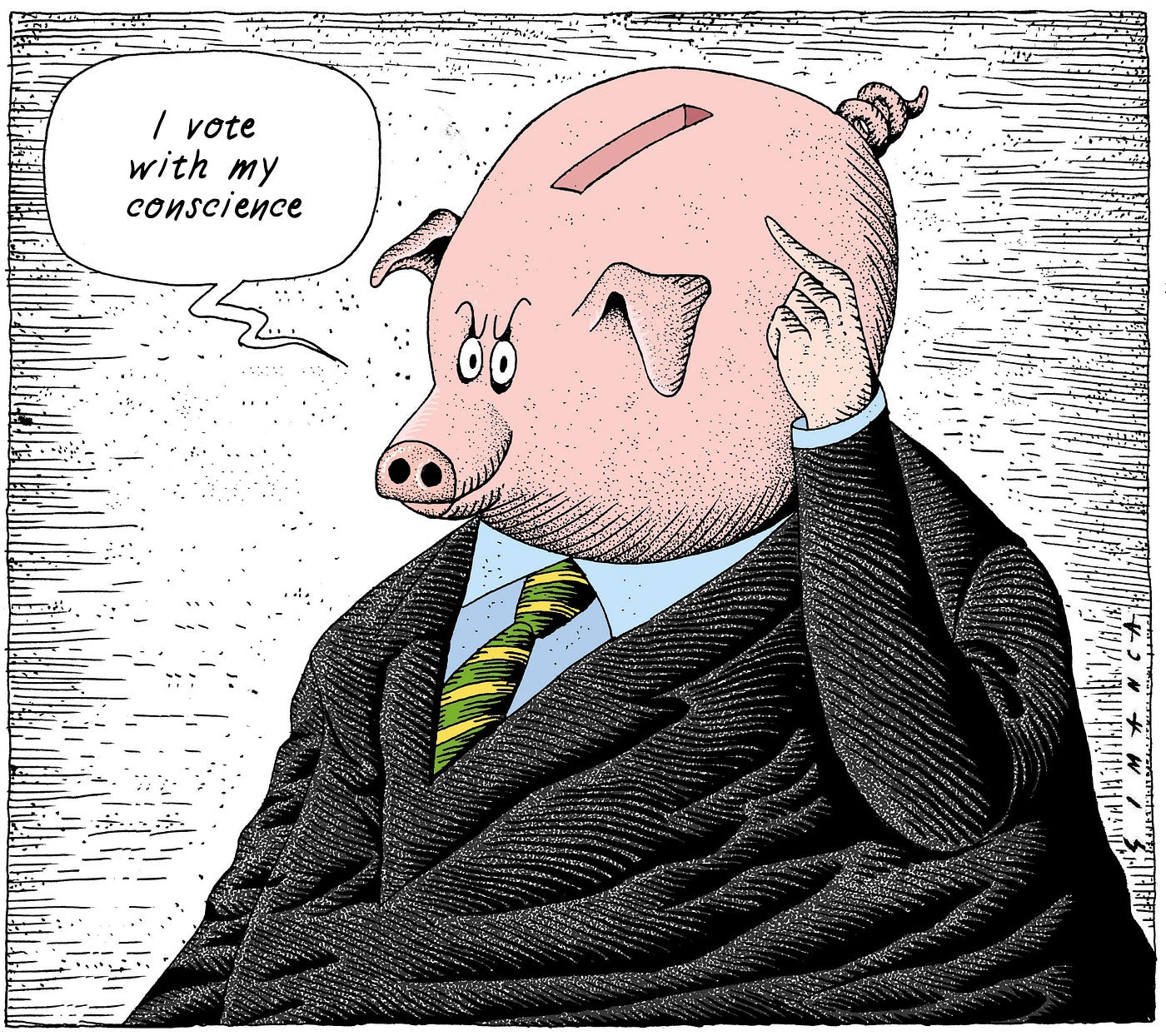

In a world that prioritizes property rights and the accumulation of capital, living ‘for’ politics, in an economic sense, can be challenging. This difficulty arises from the need to accumulate capital for survival. None of this assumes that individuals will always be in politics for money; rather, living ‘for’ politics and living ‘off’ politics can be difficult to discern amidst a world that stresses the importance of economic gain. Corrupt politicians always seem to slip through the cracks.

Weber further explores the essential roles played by both workers and entrepreneurs, isolating the entrepreneur’s intimate relationship with their enterprise, rendering them indispensable to the company. This analysis underscores the idea that individuals engaged in politics must derive their livelihood from it to accumulate capital. An entrepreneur must be present for their enterprise, otherwise they could not accumulate capital. If there were such a state whereby politicians did not need to live ‘off’ politics, then politics would be ruled by the wealthy and plutocracies would prevail. Furthermore, to highlight Weber’s main point, when politicians make a living only from being in politics — without having other sources of income — plutocracies rise.

The leadership of a state or of a party by men who (in the economic sense of the word) live exclusively for politics and not off politics means necessarily a ‘plutocratic’ recruitment of the leading political strata.

It is evident that most rational individuals would choose to not have a form of government run by the wealthy; but simultaneously, “there has never been such a stratum that has not somehow lived ‘off’ politics.” Wealth, for many is not enough: many people in power strive for increased wealth and prestige. Weber conceptualizes politics being conducted in two manners:

Either politics can be conducted ‘honorifically’ and then, as one usually says, by ‘independent,’ that is, by wealthy, men, and especially by rentiers.

Or, political leadership is made accessible to propertyless men who must then be rewarded.

Furthermore, the individuals engaging in politics are part of a party with “all party struggles are struggles for the patronage of office, as well as struggles for objective goals.” Patronage, in a political context, refers to power that is distributed to a person, organization, group, etc. from someone in a position of authority; usually, patronage is self-serving by individuals distributing power in order to server their own interests. “Some parties,” Weber states, “have become pure patronage parties handing out jobs and changing their material program according to the chances of grabbing votes.”

Rather than serving ideological or policy-oriented purposes, political parties are perceived as a means to an end. Political parties function as tools through which individual politicians can secure their livelihoods. Instead of serving the interests of the people, political parties tend to “become more and more a means to the end” of serving individual interests. At this point, we must ask ourselves the question: how can we combat this patronage within politics?

Weber explains that:

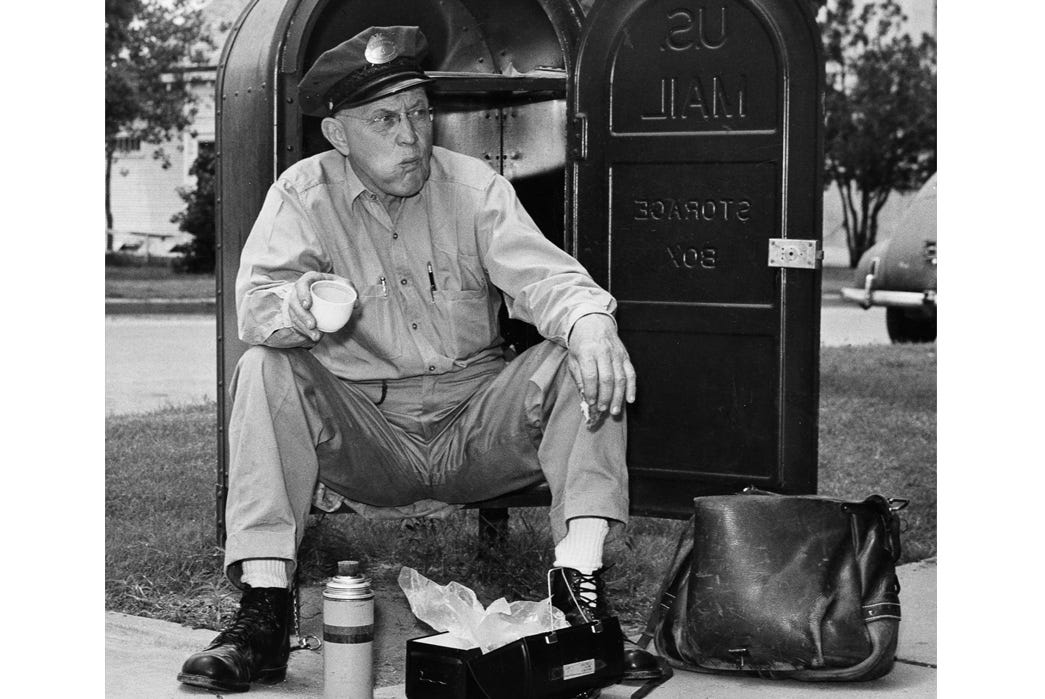

Modern officialdom into a highly qualified, professional labor force, specialized in expertness through long years of preparatory training, stands opposed to all these arrangements.

The development of a highly qualified labor force that specializes in various forms of expertness is what we are able to define as the modern bureaucracy. To be clear, Weber is not arguing that modern bureaucracies are devoid of any and all corruption; instead, Weber is explaining that there is the ability to challenge corruption in a more comprehensive manner through a professional labor force.

Weber continues:

Modern bureaucracy in the interest of integrity has developed a high sense of status honor; without this sense the danger of an awful corruption and a vulgar Philistinism threatens fatally.

Weber illustrates this concept by providing an example from a historical period in the United States, referring to this period as an era of “amateur administration.” This amateur administration was characterized by the practice of “[exchanging] officials based on the outcomes of presidential elections.” In this system, the individuals occupying various positions of power, including roles like common mail carriers, were dependent on political considerations tied to the presidency. However, this system underwent a transformation with the implementation of the Civil Service Reform, marking a departure from the previous practice. This reform was prompted by the recognition that there is an importance of having professional civil servants with lifelong dedication to their craft rather than having frequent turnover rates based on frequent political changes.

Ultimately, the developments of war, legal procedures, and other facets of society, have forced the necessity for specialized positions of power. Weber articulates:

The development of war technique called forth the expert and specialized officer; the differentiation of legal procedure called forth the trained jurist.

In these three areas — finance, war, and law — expert officialdom in the more advanced states was definitely triumphant during the sixteenth century.

The surge in the number of trained bureaucrats has unsurprisingly coincided with the emergence of “leading politicians.” In the historical context, this development was primarily driven by the necessity of alleviating the Sultan (a.k.a monarch, sovereign, etc.) from tackling personal responsibilities. The rationale behind such a transformation lies in the recognition that a city-state leader engaging in individual tasks and decision-making runs the risk of weakening the government. Weber notes:

In the Occident, influenced above all by the reports of the Venetian legates, diplomacy first became a consciously cultivated art in the age of Charles V, in Machiavelli’s time. (emphasis mine)

The need for a centralized guidance of the entire governmental policy depends upon constitutional development. Advisers, leaders, and other influential figures existed prior to this formalization, but the development of administrative structures followed different paths. “The prince,” Weber writes, “surrounded himself with purely personal confidants — ‘the ‘cabinet’ — and through them rendered his decisions.” Yet, there was an apparent conflict between the proper functioning of government (with expert officials) and the prince wanting to maintain leadership in his own hands.

Weber notes:

This struggle between expert officialdom and autocratic rule was widespread until the emergence of parliaments, where the dynamics changed.

The emergence of parliaments cultivated a setting in which the monarch could remain aloof from party struggles, enabling a sole individual, specifically the minister, to serve as the public representative of the government and assume responsibility. “All these interests,” Weber states, “worked together and in the same direction: a minister emerged to direct the officialdom in a unified way.”

In England, “the development of parliamentary power worked even more strongly in the direction of a unification of the state apparatus.” Though the parliament itself was powerful, in England, they formed a smaller group within the parliament called the ‘cabinet’, with the leader of the cabinet also being the leader of the whole parliament. Weber explains:

This party power was ignored by official law but, in fact, it alone was politically decisive.

The official collegial bodies as such were not organs of the actual ruling power, the party, and hence could not be the bearers of real government.

Thus, even though England’s government had various organs that were explicitly designed to carry out various laws, there was an overarching party power that functionally predetermined these laws. “The English system,” Weber writes, “has been taken over on the Continent in the form of parliamentary ministries.” Many other forms of government follow a similar structure, though many also operate differently.

For example:

The American system placed the directly and popularly elected leader of the victorious party at the head of the apparatus of officials appointed by him and bound him to the consent of ‘parliament’ only in budgetary and legislative matters.

For Weber, politics has been developed into an organization with “the separation of public functionaries into two categories.” These categories are:

- ‘Political’ Officials: “… Can be transferred any time at will, that they can be dismissed, or at least temporarily withdrawn.”

- ‘Administrative’ Officials: Cannot be transferred anytime at will; this is the “‘independence’ of officials with judicial functions.”

Of course, we could spend a lot of time analyzing the differences between ‘political’ and ‘administrative’ officials, but we’ve already been doing that. The important undertaking here consists of examining the political element:

The political element consists, above all, in the task of maintaining ‘law and order’ in the country hence maintaining the existing power relations.

Weber, above all, is interested in the nature of politicians and their followers:

We shall [ … ] ask for the typical peculiarity of the professional politicians, of the ‘leaders’ as well as their followings.

Their nature has changed and today varies greatly from one case to another.

Major Types of Professional Politicians

Weber isolates five types of professional politicians that will be explained here through five stratums.

“Confronting the estates, the prince found support in politically exploitable strata outside of the order of the estates.” (emphasis mine)

Therefore, the differentiation between the types of professional politicians concerns who the prince politically exploits.

**Note: Though Weber is referring to ‘the prince’, this is derived from his reference to Machiavelli’s The Prince, desribing leaders who seek to maintain legitimacy. This does not mean that all despotic societies concerned a literal price as leaders go by many names.

First Stratum

The clergy — formal leaders within established religions — concerns the first stratum. Weber writes that “the clergy were technically useful because they were literate.” Their employment as political counselors was useful in the leader’s struggle. And, because religious figure are not supposed to strive for power, they were not deemed threatening by those in power.

The cleric, especially the celibate cleric … was not tempted by the struggle for political power.

I find it intriguing that Weber starts with the clergymen being the first employed political counselors because it appears that they give the leader/government some type of spiritual legitimacy. In this way, opposing the prince is akin to challenging divine authority.

Second Stratum

“The humanistically educated literati” concerns the second stratum. Weber writes:

There was a time when one learned to produce Latin speeches and Greek verses in order to become a political adviser to a prince and, above all things, to become a memorialist.

It must be noted that this second stratum was “developed and modeled after Chinese Antiquity.” Weber notes that the era of the humanistically educated literati had little impact on Western culture and did not yield profound results compared to that of Eastern culture. Weber cites Li Hongzhang (Born: 1823; Died: 1901) and how Hongzhang’s poetry serves as an example of how memorialists advance the legitimacy of a state.

Though the first stratum grants the state a sense of divinity, the second stratum appears to grant the state a history — a shared past for every member of the state. However, I would probably contest Weber’s conceptualization of memorialization not being as impactful on Western culture. I would posit that Western culture is more keen on tying historicity to religion; therefore, the clergymen are able to serve as both the first and second stratum for Western culture. Or maybe, in some cultures, memorialization of the state can be like that of a religion. Regardless, elements of religiosity and memorialization are characteristics of a state.

Third Stratum

Court nobility concerns the third stratum. The nobles, characterized as a wealthy and influential class, have political influence. In order for the king or prince to consolidate power (to become more powerful), they might take actions that diminish the political power of the nobles. However, rather than stripping the nobles of all power, “[the prince] drew the nobles to the court and used them in their political and diplomatic service.” This strategy centralizes authority by structuring the education system to align with the interests and capabilities of the nobility, who are actively involved in political governance. Why would the prince want to bother with the threat of a strong aristocracy?

Fourth Stratum

The ‘gentry’ concerns the fourth stratum. A quick Google search defines “gentry” as:

people of good social position, specifically (in the UK) the class of people next below the nobility in position and birth.

In the fourth stratum, the gentry is primarily involved in local administration. Typically, individuals within the gentry derive their wealth from land ownership. Weber identifies that:

The prince placed the stratum in possession of the offices of ‘self-government,’ and later he himself became increasingly dependent upon them.

Because the prince has many priorities, the gentry relieves the prince of certain responsibilities by having power over local affairs.

The gentry maintained the possession of all offices of local administration by taking them over without compensation in the interest of their own social power.

The gentry has saved England from the bureaucratization which has been the fate of all continental states.

Fifth Stratum

The “university-trained jurist” concerns the fifth stratum. The university-trained jurist is “peculiar to the Occident” and “has been of decisive significance for the Continent’s whole political structure.” Essentially, Weber finds the university-trained jurist to be strategic in maintaining a state’s power.

Originating from Roman law, it is evident that trained jurists are concerned with “the direction of the evolving rational state.” Trained jurists allow the state to operate more efficiently and align with the ever-evolving culture by analyzing the structure of government in order to make it more rational.

Weber remarks on the association of jurisprudence with theories of natural law, which have now become commonly accepted modes of thinking:

The usus modernus of the late medieval pandect jurists and canonists was blended with theories of natural law, which were born from juristic and Christian thought and which were later secularized

This reminds me of the first stratum where the state is blessed with the divinity from the clergyman. And, the fifth stratum is explaining how the state has always been underpinned by natural law. Weber states:

Without this juristic rationalism, the rise of the absolute state is just as little imaginable as is the Revolution.

Since the French Revolution, the modern lawyer and modern democracy absolutely belong together.

Weber continues highlighting the importance of lawyers in upholding the means of the state. He writes that “the management of politics through parties simply means management through interest groups.” In this case, the lawyer, who is skilled in advocating for specific interests, is necessary in this political landscape as “only the lawyer successfully pleads a cause that can be supported by logically strong arguments, thus handling a ‘good’ cause ‘well’”. This is in opposition to the politician who “turns a cause that is good in every sense into a ‘weak’ cause, through technically ‘weak’ pleading.”

Proper Vocation

After Weber discusses the five stratums, he explains that, according to the genuine official’s proper vocation, the genuine official “will not engage in politics.” Instead, Weber states that the “[genuine official] should engage in impartial administration.’” This entails the genuine official carrying out tasks without favoritism or personal biases. For Weber, it is vital that administrative decisions are based on objective criteria rather than subjective beliefs; he uses the phrase “sine ira et studio” to describe the role and attitude of the genuine official. Sine ira et studio is Latin for “without scorn or bias.”

“Hence”, Weber states, “[the genuine official] shall not do precisely what the politician, the leader as well as [their] following, must always and necessarily do, namely, fight.”

On the other hand, the politician’s nature starkly contrasts that of the genuine official. The politician must “take a stand” and “be passionate”, encompassing the elements of what constitutes a political leader. Civil servants differ from the politician based on their “ability to execute conscientiously the order of the superior authorities, exactly as if the order agreed with his own conviction.” Even if an order appears to be wrong, the civil servant carries out their task as the authority insists on the order. Without this “moral discipline” and “self-denial” of the civil servant, “the whole apparatus would fall to pieces.”

At any rate, “let us return once more to the types of political figures.”

Types of Political Figures (Cont.)

Demagogue

Weber continues:

Since the time of the constitutional state, and definitely since democracy has been established, the ‘demagogue’ has been the typical political leader in the Occident.

When one hears the word ‘demagogue’, it is easy to instinctively respond with a sense of aversion. However, we must not “forget that not Cleon but Pericles was the first to bear the name of demagogue.” Cleon was an Athenian general with a populist and assertive political style; he is most often than not associated with demagoguery. However, Weber highlights that Pericles was the first to be truly called a demagogue, even though Pericles was pivotal in leading the Athenian democracy.

Pericles led the sovereign Ecclesia of the demos of Athens as a supreme strategist holding the only elective office or without holding any office at all.

Journalist

At any rate, Weber states that modern formations of demagoguery “makes use of oratory” through a litany of public speeches from leaders, though, he finds the use of printed words to be “more enduring.” Weber states that “the political publicist, and above all the journalist, is nowadays the most important representative of the demagogic species.” (In the realm of the media being considered the fourth branch of government, this rings true.)

Weber admits that, within the parameters of his lecture(s), there is an impossibility sketching “the sociology of modern political journalism.” Instead, Weber offers particular elements of what constitutes modern political journalism, with the first quality being the lack of a “fixed social classification.” Though complete objectivity is difficult in writing — if not impossible — journalists lack fixed social classifications through their independence. Journalism should report on the facts of an issue from an outsider’s perspective. However, Weber notes that “the journalist belongs to a sort of pariah caste, which is always estimated by ‘society’ in terms of its ethically lowest representative.”

According to Weber, journalists find themselves marginalized or placed in a lower social caste because individuals homogenize journalists based on the unethical behavior of one journalist. This is why “a really good journalistic accomplishment requires at least as much ‘genius’ as any scholarly accomplishment.” At the same time, “irresponsible journalistic accomplishments and their often terrible effects are remembered.”

Individuals often undervalue journalists, sometimes considering themselves to possess comparable or superior competence. Furthermore, there is a widespread sentiment of distrust towards the media, with many perceiving journalists as having a biased agenda. Weber points out that although many journalists have found it difficult to occupy a position of political leadership, “the journalist has had favorable chances [for political leadership] only in the Social Democratic party.” However, he observes that such roles within the party are primarily editorial rather than official.

Weber continues in stating that “the chances for ascent to political power” for journalists in bourgeois parties is increasingly difficult. Though “every politician … has needed influence over the press and hence has needed relations with the press,” the ability to have party leaders “ merge from the ranks of the press” has shown to be a near impossibility. Weber states:

The necessity of gaining one’s livelihood by the writing of daily or at least weekly articles is like lead on the feet of the politicians.

To continue, “our great capitalist newspaper concerns … have been regularly and typically the breeders of political indifference.” All modern day newspapers — whether it be an antiquated physical copy or a digital one — contain advertisements. All successful news outlets are for-profit corporations. Because of this, “no profits could be made in an independent policy.” Therefore, profitable news outlets benefit from bias by gaining a niche set of followers who succumb to more particularized advertisements. Weber writes:

The advertising business is also the avenue along which, during the war, the attempt was made to influence the press politically in a grand stylean attempt which apparently it is regarded as desirable to continue now.

One might assume that large newspaper companies might “escape this pressure,” but that would be wrong. In fact, “by dropping anonymity [media outlets] strove for and attained greater sales.” They have a clear incentive to gain fortune: “the publishers as well as the journalists of sensationalism have gained fortunes but certainly not honor.” Yet, the life of a journalist — a true journalist, carrying out the art of journalism — “is an absolute gamble in every respect and under conditions that test one’s inner security in a way that scarcely occurs in any other situation.”

Weber writes:

It is no small matter that [journalists] must express themselves promptly and convincingly about this and that, on all conceivable problems.

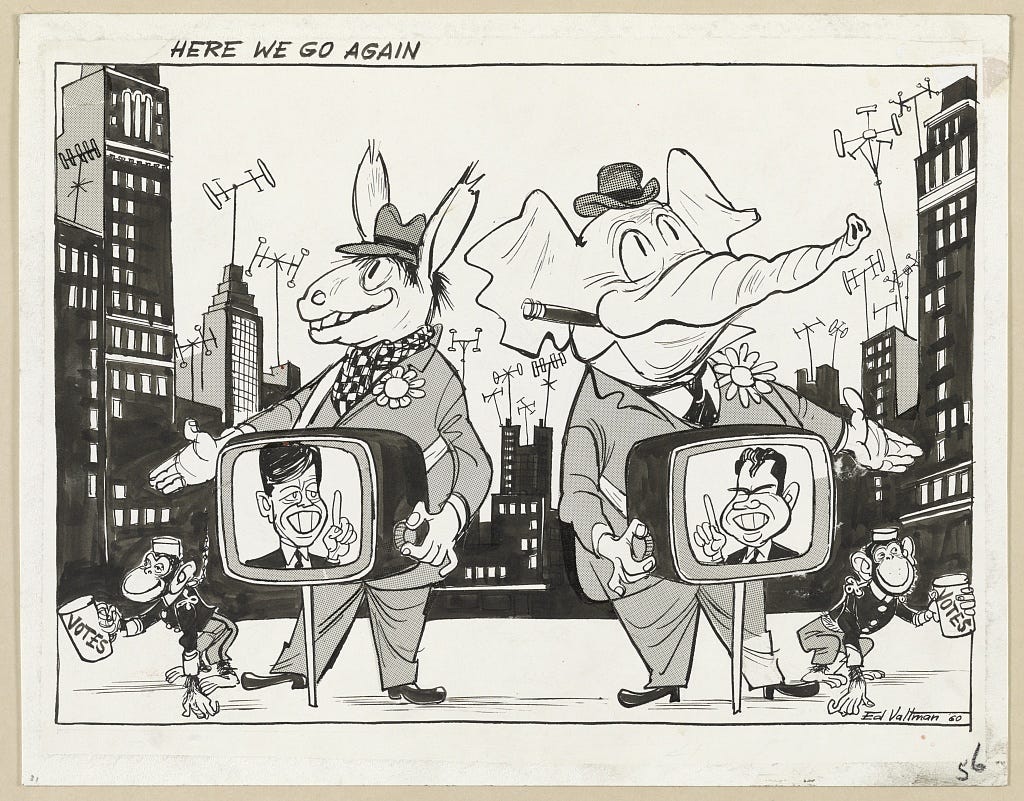

Political Parties and Political Associations

Political associations are “associations going beyond the sphere and range of the tasks of small rural districts where powerholders are periodically elected.” Weber emphasizes the importance of political organization by arguing that it would be nearly impossible to sustain a political association without organization. He writes:

It is unimaginable how in large associations elections could function at all without this managerial pattern.

Every political party, irrespective of its nature, demands a certain level of organization and management. While active leadership is essential in all political associations, Weber notes that the specific structures of parties vary significantly. An example of diverse party structures that still exhibit comparable organizational patterns can be found in Weber’s comparison of the “medieval cities, like those of the Guelfs and the Ghibellines,” and the structure of “Bolshevism and its Soviets.” Though Bolshevism constitutes a revolutionary movement composed of Soviet Leninists and Marxists aimed at overthrowing the state, it is still conceptualized as a party. Weber notes that in both medieval cities and Bolshevism, there existed influential individuals and followers, a strictly organized military, surveillance networks, the revocation of certain political rights to limit influence from the outside, and confiscation policies.

“Parties, in the sense usual with us,” Weber states, “were at first … pure followings of the aristocracy.” It should come as no surprise that aristocratic parties were close with the parties of notables whose classes rise with the power of the bourgeois. At any rate, Weber describes that parties of all kinds were initially formed based on major stratums of society like those of class interest, family traditions, and ideological reasons. Weber writes:

Clergymen, teachers, professors, lawyers, doctors, apothecaries, prosperous farmers, manufacturers — in England the whole stratum that considered itself as belonging to the class of gentlemen — formed, at first, occasional associations at most local political clubs.

These “political clubs” were organized at a local, grassroots level. Political clubs provided individuals the capacity to meet with one another and engage in political activities. Weber speaks highly of these clubs, explicating that “leadership of the clubs is an avocation and an honorific pursuit, as demanded by the occasion.”

Nevertheless, in situations where these local political clubs are absent, which is often the case, the “quite formless management of politics … lies in the hands of the few people constantly interested in it.” Weber illustrates this point by highlighting that, in a situation without political clubs, the journalist functions as the only paid, professional politician, and the management of the newspaper functions as the political organization. Regarding parliamentary delegates, their task is easily simplified without political clubs as the only need to consult local notables to formulate policies. Thus, the political clubs are necessary; their existence compels politicians to engage with the general populace — the common individual — rather than solely adhering to the principles of the notables.

Weber continues by analyzing the widespread influence that individuals had in political management, particularly in the context of material interests. He explains that decisions in ministerial departments were often made “with a view to their influence upon electoral chances.” In fact, “each and every kind of wish was sought through the local delegate’s mediation” culminating in everyone striving for such influence. Deputies and elected officials held control over patronage, “maintaining connections with the local notables.”

(Modern) Political Parties and Political Associations

Evidently, Weber contrasts earlier eras of politics by isolating that “the most modern forms of party organizations stand in sharp contrast to [the previous era’s] idyllic state.” In previous eras, groups of notables and members of parliament held significant political power, refraining from adhering to the general populaces’ demands. However, Weber speaks of the modern era being in opposition to the rule of the notables:

These modern forms are the children of democracy, of mass franchise, of the necessity to woo and organize the masses, and develop the utmost unity of direction and the strictest discipline. The rule of notables and guidance by members of parliament ceases.

The modern context allows for the rise of ‘professional’ politicians operating outside of parliament. These ‘professional’ politicians act as “entrepreneurs” or as “officials with a fixed salary.” Here, Weber is explaining a shift in politics where individuals now have the ability to engage in politics from the outside of parliament. Within the context of modern party organizations, “power … rests in the hands of those who, within the organization, handle the work continuously.” Alternatively, if power is not concentrated in the hands of those actively involved in organizational work, then “power rests in the hands of those on whom the organization in its processes depends financially or personally.”

- *Note: Weber uses the example of Tammany Hall to illustrate power being concentrated in the hands of those whom the organization depends on for finances.

At this juncture, Weber introduces the concept of the “political machine” characterized as the “whole apparatus of people … who direct the machine, [keeping] the members of the parliament in check.” The development of the political machine marks the rise of what Weber calls the plebiscitarian democracy. Plebiscitarian democracy refers to a governmental structure whereby leaders derive authority from popular support, usually bypassing traditional party and political structures.

Regardless, the party that supported the winning victor — more specifically, the party official and party entrepreneur — “naturally expect personal compensation … or other advantages.” Weber writes:

They expect that the demagogic effect of the leader’s personality … will extend opportunities to their followers to find the compensation for which they hope.

- *Note: Weber makes a quick comment here about the charismatic effect of a leader being of extreme importance here.

Nonetheless, there is always tension between groups striving for power and influence, most notably with notables and members of parliament ‘wrangling’ for influence. Among these groups, there is disagreement about who ought to lead; and when there is no clear leader, problems arise. Yet, even when a leader is found, “concessions of all sorts must be made to the vanity and the personal interest of the party notables.” Weber explains that even though concessions must be made, “‘officials’ submit relatively easily to a leader’s personality if it has a strong demagogic appeal.”

As stated earlier, many individuals are charmed by the charismatic qualities of a leader — especially if they have a strong voice and tenacious demeanor. “Inwardly,” Weber says, “it is per se more satisfying to work for a leader” rather than a system where power is completely dispersed. People like people that they are familiar with. Weber continues:

The rural but also the petty bourgeois voter looks for the name of the notable familiar to him. He distrusts the man who is unknown to him. (emphasis mine)

Two Structural Forms: The Notables and The Party

England

In order to differentiate between the notables and the party, Weber first utilizes the structure of England’s government as an example.

“First England,” Weber writes, “there until 1868 the party organization was almost purely an organization of notables” (emphasis mine). The notables had power and influence over England’s political system due to their wealth and prestige. The notables constituted the “pillars of the political organization.” There also stood parliament, with the members being at the whim of the notables along with with parties, the cabinet, and the leader. Alongside the leader existed the ‘whip’ which Weber distinctively notes as “the most important professional politician of the party organization.” To be more clear:

Patronage of office was vested in the hands of the ‘whip’; thus the job hunter had to turn to him and he arranged an understanding with the deputies of the individual election boroughs.

And, to no surprise, these job hunters were often notables or deemed legitimate or not by the notables. Along with the job hunters, “a capitalist entrepreneurial type developed in the boroughs”; this was known as the ‘election agent’ who gained money by running election campaigns and controlling the finances of the operation. At the time, legislation in England “aimed at controlling the campaign costs of elections” to which election agents gained more popularity; “for in England, the candidate …enjoyed stretching his purse.” Due to this, “the election agent made the candidate pay a lump sum.”

Thus, prior to 1868, the notables had strong power and influence over England’s government. However, since 1868, the ‘caucus’ system was developed in England; “the occasion for this development was the democratization of the franchise.” The introduction of the caucus system required politicians to win over the masses, marking an apparent transformation from the notables controlling the structure of government and leadership to a “tremendous apparatus of democratic associations.”

Weber explains the impacts of the caucus system and the emergence of democratization:

Hence, hired and paid officials of the local electoral committees increased numerically; and, on the whole, perhaps 10 percent of the voters were organized in these local committees.

Therefore, England had a “newly emerging machine” which was no longer led, structured, or manages by the notables or members of parliament. Weber states that “the machine came out of the fight so victoriously that the whip had to submit and compromise with the machine.”

Ultimately, the caucus system did not at all decentralize power. In fact:

The result was a centralization of all power in the hands of the few and, ultimately, of the one person who stood at the top of the party.

In both structural forms, whether it be the notables or the party, power is centralized; however, when power is solely centralized in the hands of the notables, the general populace does not have stake in determining how that power is exercised. In contrast, the caucus system allows the people to elect a leader, placing the leader in a position of concentrated power.

Weber proceeds to describe how “such machinery requires a considerable personnel.” At the time of his writing, he states that, in England, “there are about 2,000 persons who live directly off party politics” along with numerous individuals actively engaging in politics as job seekers. Yet, even though this machine has many active participants, we must not be fooled in assuming that this machine makes a governmental system immune from corruption. Weber understands that, today, many members of parliament “are normally nothing better than well-disciplined ‘yes’ men.” If a strong leader controls the machine, members of parliament are functionally at the whim of the leader: “[Parliament members] must appear when the whips call [them], and do what the cabinet or the leader of the opposition orders.” In this case, the leader is like that of a dictator; to which, Weber states:

Therewith the plebiscitarian dictator actually stands above Parliament. He brings the masses behind him by means of the machine and the members of Parliament are for him merely political spoilsmen enrolled in his following.

At this point, we must echo Weber’s question: “How does the selection of these strong leaders take place?” There is no doubt that “the force of demagogic speech is above all decisive.” By appealing and assuaging the masses, demagogues continue to rise and seldom experience a rapid decline. Currently, “often purely emotional means are used”; on this point, Weber references the Salvation Army as an example of an organization utilizing emotional appeal to garner support.

My favorite line in Politics as Vocation is this:

One may call the existing state of affairs a ‘dictatorship resting on the exploitation of mass emotionality.’

Granted, Weber does mention that the “highly developed system of committee work” in the English Parliament attempts to train individuals how to become better, more experienced leaders. Weber argues:

The practice of committee reports and public criticism of these deliberations is a condition for training, for really selecting leaders and eliminating mere demagogues.

America

Next, Weber utilizes the structure of America’s government to explain the transformation of a government being driven by the notables to the parties. He notes that England’s caucus system was incredibly weak compared to America’s party organization.

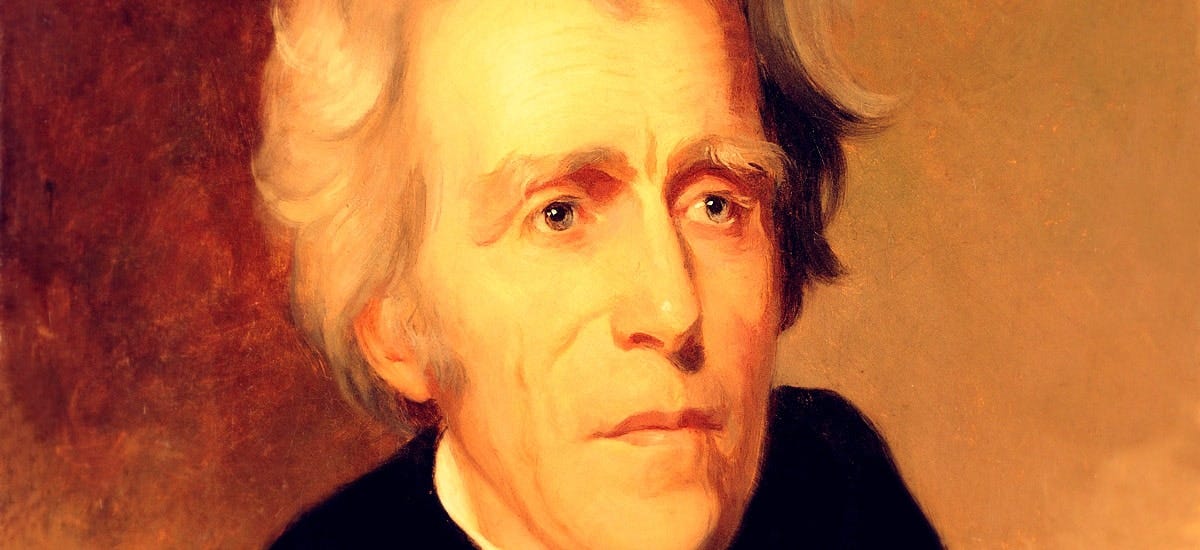

Initially, “Washington’s idea” envisioned America as a “commonwealth administered by ‘gentlemen’”, where gentlemen were synonymous with landlords or men with a college education. During the early stages of party organization, “the members of the House of Representatives [claimed] to be leaders,” akin to the notables in England. However, this paradigm shifted with the election of Andrew Jackson as President, who assured that “the old traditions were overthrown.” In examining these early elements and developments of the plebiscitarian machine, Weber emphasizes the distinctive structure of America’s government, wherein the “chief of office-patronage” (President) is elected by plebiscite.

Because of America’s structure of government, the President holds a unique position owing to the doctrine of the ‘separation of powers’:

By virtue of the ‘separation of powers’ [the President] was almost independent of parliament in [their] conduct of office.

During Jackson’s presidency, the “spoils system”, defined by political favors such as appointments and financial incentives, became systemic and ingrained in the political landscape. This system elevated the significance of the presidency. As a result, individuals seeking to occupy the seat of presidency were motivated to pursue victory at any cost.

The spoils system awards those who are loyal to the victorious candidate. This entails that “quite unprincipled parties oppose one another”; or in simpler terms, political parties are purely concerned with obtaining political appointments rather than adhering to a strict set of principles. Individuals’ platforms are always in a constant state of flux as individuals change their positions to maximize their chances of winning votes or being appointed by the President. Weber writes that “[political formations] are purely organizations of job hunters drafting their changing platforms according to the chances of votegrabbing.”

- *Note: This reminds me of various Republican politicians who claimed that Donald Trump was unfit for office, then spoke highly of Trump once he won the nomination.

Weber succinctly writes:

The parties are simply and absolutely fashioned for the election campaign that is most important for office patronage: the fight for the presidency and for the governorships of the separate states.

The fight for the presidency is not an easy one; Weber continues by explaining the importance of a political party’s organization. He describes the process of parties choosing candidates (though he might be too optimistic in assuming that national conventions are purely democratic). Weber states:

Platforms and candidates are selected at the national conventions of the parties without intervention by congressmen.

Hence they emerge from party conventions, the delegates of which are formally, very democratically elected.

**Note: Bernie Sanders lost the delegation at the Democratic National Convention even though he had more votes than Hillary Clinton. Weber may be too optimistic on the point of delegates being democratically elected.

Further still, within the parties, “the most embittered fight rages about the question of ‘nomination.’” There are hundreds of thousands of official appointments that lie in the hands of the president — and everyone seems to want a piece of the pie. Therefore:

The President, who is legitimatized by the people, confronts everybody, even Congress; this is a result of ‘the separation of powers.’

Weber makes clear that the spoils system is problematic and “could not exist without enormous evils.” Yet, this corruption is tolerated because America is the land of “unlimited economic opportunities”; money can be wasted, but this wasteful spending is offset by various economic opportunities.

The Boss

To continue, Weber discusses the boss as a “figure who appears in the picture of this system of the plebiscitarian party machine.” The boss can be defined as:

A political capitalist entrepreneur who on [their] own account and at [their] own risk provides votes.

Initially, the boss establishes themselves as “a lawyer or a saloonkeeper or as a proprietor of similar establishments.” Then, they leverage the network that they have built in order to gain control over a specific number of votes. As they ascend in social standing, bosses attract other bosses, further advancing their position. In the context of party politics, the boss plays a crucial role in centralizing power. In fact, they are integral in securing the party’s financial means. While contributions from members, random taxes on salary, along with bribes and tips, contribute to these financial resources, Weber notes, “this alone is not enough to accumulate the necessary capital for political enterprises.” Therefore the boss is also “indispensable as the direct recipient of the money of great financial magnates.” Money must come from somewhere.

The boss’ objective is not to seek social honor or status. Rather, the boss seeks to attain power, viewing power as a means of generating wealth and power as an end in itself. Weber states that “the American boss works in the dark” and is not a public figure. Since the typical boss does not attempt to seek social status, “he accepts no office, except that of senator,” given that senators “participate in office patronage.”

The boss is primarily focused on strategies that capture votes, often lacking a strong educational background and definitive political principles. While maintaining and “inoffensive and correct private life,” the boss constantly adjusts to the standards of political conduct deemed necessary in the political arena. The boss’ disinterest in attaining political office becomes advantageous for political parties, enabling individuals outside the party, such as intellectuals or notables, to run for office, broadening the party’s appeal to the public. Although “the bosses resist an outsider who might jeopardize their sources of money and power,” the competitive struggle to win over voters has compelled many bosses to accept candidates opposed to political corruption.

Capitalist Party Machine

Various clubs propagate the existence of a powerful “capitalist party machine.” Examples like Tammany Hall, mentioned previously, “seek profits solely through political control.” These clubs wield significant influence in the outcome of elections and the structure of political administration. Though these clubs often sold themselves as a public forum for any and all workers, the clubs were purely motivated by profit.

At this juncture, Weber explores the situation of the workers:

When American workers were asked why they allowed themselves to be governed by politicians whom they admitted they despised, the answer was: ‘We prefer having people in office whom we can spit upon, rather than a caste of officials who spit upon us, as is the case with you.’

This was the old point of view of American ‘democracy.’

Despite initially accepting their oppression, the implementation of different reforms, such as the Civil Service Reform, brought about the perspective that active political engagement, rather than adhering to apathetic tendencies, holds the potential to reshape governmental structures. Weber writes:

The spoils system will thus gradually recede into the background and the nature of party leadership is then likely to be transformed also but as yet, we do not know in what way.

Decisive Conditions of Political Management

In the following section, Weber discusses three key aspects that shape “the decisive conditions of political management” of his home country, Germany.

- “The parliaments have been impotent.” The German parliaments appeared unattractive to individuals with virtuous leadership qualities because they lacked power. Many felt that entering Parliament was a dead end because there were not opportunities to achieve significant impacts.

- “The tremendous importance of the trained expert officialdom.” Weber notes that the officialdom predetermined the state of Parliament because “officials claimed not only official positions but also cabinet positions for themselves.” This dual role became problematic, as seen in the Bavarian state legislature; essentially, “it was said that if members of the legislature were to be placed in cabinet positions talented people would no longer seek official careers.” The argument present was that if this practice of dual roles continued, skilled professionals would be drawn into politics, potentially resulting in a shortage of qualified officials in their respective fields.

- “We have had parties with principled political views who have maintained that their members … represented bonafide Weltanschauungen.” Weber illustrates this by examining the prevalence of the Catholic Centre Party and the Social Democratic party. Both of these parties, serving as minority parties, opposed parliamentary democracy due to the concern that being in the minority would result in a loss of representation. However, this made it increasingly difficult for the parliament to function: “the fact that both parties dissociated themselves from the parliamentary system made parliamentary government impossible.”

Thus, due to the decisive conditions of political management in Germany, professional politicians had little power. Guild instincts, characterized as a mindset of exclusivity over a matter, began emerging amongst these politicians. Many politicians lost any potential for power, leading to tragic political careers as they could not be accepted by the existing notables. Weber cites the example of August Bebel, a leader who “never betrayed confidence in the eyes of the masses, [resulting] in his having the masses absolutely behind him.” Yet, with Bebel’s death, leadership gave way into increased bureaucratization.

Weber continues:

Since the eighteen-eighties the bourgeois parties have completely become guilds of notables.

The notion that bourgeois parties consisted of groups of notables should come as no surprise. However, there are times when “the parties had to draw on extra-party intellects for advertising purposes.” It must be known that these parties avoided letting these intellects run for election. Weber makes clear:

Our parliamentary parties were and are guilds.

Every speech delivered from the floor of the Reichstag is thoroughly censored in the party before it is delivered.

Therefore, in a way, it appears that the party precedes discourse.

Revolution: Weber’s Quick Comment

Throughout this blog, we have been discussing political structures and organizations, but we must ask what happens when these structures collapse. This is what Weber calls “the Revolution”. Rather than assuming a holistic transformation post-revolution, Weber elucidates that different types of party apparatuses emerge after revolutions; he specifically mentions two types:

- “First, there were amateur apparatuses.” This is what Weber refers to as “students of various universities” who offer their services to undertake political work on their behalf.

- “Secondly, there are apparatuses of businessmen.” This is what Weber refers to as individuals “willing to take over the propaganda, at fixed rates for every vote.”

Weber does not make a definitive judgement about which apparatus is “better” than the other, but he briefly mentions that the apparatuses of businessmen are (probably) more effective than the amateur apparatuses. Regardless, these apparatuses come and go, existing in a state of flux.

Plebiscitarian Leadership

Weber explores the relationship between plebiscitarian leaders and their followers:

The plebiscitarian leadership of parties entails the ‘soullessness’ of the following, their intellectual proletarianization, one might say … The following of such a leader must obey him blindly.

Rather than normatively arguing plebiscitarian leadership as being “good” or “bad”, Weber examines that “there is only the choice between leadership democracy with a ‘machine’ and leaderless democracy.” Plebiscitarian leadership crafts a devout following of leaders, where individuals obey their leaders without question, yet this form of leadership employs a well-organized political machine. In fact, Weber suggests that only the plebiscitarian election of the President “could become the safety-valve of the demand for leadership.” However, the future formation of parties remains uncertain due to “the very petty-bourgeois hostility of all parties to leaders.”

Politics as a Vocation

We must remind ourselves of the definition for politics as a vocation: either one lives ‘for’ politics or one lives ‘off’ politics.

According to Weber, there is an uncertainty regarding the available routes for individuals seeking to engage in politics. For those who are “compelled to live ‘off’ politics”, Weber finds that these individuals “almost always have to consider the alternative positions of the journalist or the party official as the typical direct avenues.” Or, this individual has the capability to occupy the position as a representative of an interest groups (such as a union or bureau). This career path is not for the faint of heart; Weber advises those who lack inner resilience and the ability to accept failure ought to avoid this career path. Weber states:

[The individual] who is inwardly defenseless and unable to find the proper answer for himself had better stay away from this career … It is an avenue that may constantly lead to disappointments.

Transitioning away from financial considerations, Weber asks: “What inner enjoyments can this career offer and what personal conditions are presupposed for one who enters this avenue?” The first answer that Weber gives is that politics “grants a feeling of power.” This power — power that influences men and makes one feel that they are of grave importance in history — can truly elevate a politician’s self-esteem. Yet, the question does not end here; we now must ask how justice is able to prevail through one’s exercise of power. Weber highlights three pre-eminent qualities that are necessary for the politician: passion, a feeling of responsibility, and a sense of proportion.

First is passion: “This means passion in the sense of matter-of-factness, of passionate devotion to a ‘cause’ …” A necessary quality for the politician is that of passion; they must be devoted to the causes that they are advocating for.

Second is a feeling of responsibility: Weber draws a sharp distinction between the perilous “romanticism of the intellectually interesting” (which tends to be void and lacking sense of responsibility), and a genuine, authentic feeling of responsibility. The politician must feel that it is their responsibility to change the state of social affairs in some way, shape, or form.

Third is a sense of proportion: The third quality entails a fundamental balance between passion and responsibility. Weber highlights this sense of proportion as “the decisive psychological quality of the politician.” He defines proportion as the “ability to let realities work upon [the politician] with inner concentration and calmness.” For a politician, maintaining a particular distance is imperative; this does not imply that politicians are emotionally cold but emphasizes the need for politicians to not be influenced by their personal feelings. “Politics is made with the head,” Weber states, “not with other parts of the body or soul.”

On the third point, Weber writes:

That firm taming of the soul, which distinguishes the passionate politician and differentiates him from the ‘sterilely excited’ and mere political dilettante, is possible only through habituation to detachment in every sense of the word.

These three points culminate in the politician fighting a common adversary:

Therefore, daily and hourly, the politician inwardly has to overcome a quite trivial and all-too-human enemy: a quite vulgar vanity, the deadly enemy of all matter-of-fact devotion to a cause, and of all distance, in this case, of distance towards one’s self. (emphasis mine)

Though the average individual argues that vanity is a problematic quality, Weber argues that perhaps “nobody is entirely free from it.” However, in other occupations, like that of occupations within academia, vanity is “relatively harmless.” We must be aware that, for the politician, vanity serves of higher importance; the politician is striving for power. Weber discusses “two kinds of deadly sins” within politics:

- Lack of Objectivity

- Irresponsibility

“Vanity … tempts the politician to commit one or both of these sins.”

At any rate, the strength of a political action derives from the belief in a cause; it appears to be a amtter of faith for the politician. “The politician,” Weber says, “may be sustained by a strong belief in ‘progress’ … [or] he may coolly reject this kind of belief.”

The Ethos of Politics

Weber proceeds to examine the relationship between ethics and politics. Illustrating his point with examples such as a man justifying infidelity by blaming his wife or a defeated individual attributing the loss to fighting for an immoral cause, Weber argues the relying on external ethical justifications is problematic. Instead, Weber argues for a more objective approach: emphasizing objective interests and future responsibilities rather than dwelling on questions of past guilt.

Weber asserts that the exploitation of ethics in this manner is trouble:

If anything is ‘vulgar,’ then, this is, and it is the result of this fashion of exploiting ‘ethics’ as a means of ‘being in the right.’

Yet, what truly is the relationship between ethics and politics? Weber notes that there are various views: some believe ethics and politics have nothing to do with one another while others believe that ethics and politics have everything to do with each other. Regardless, Weber challenges these totalizing views by examining the diversity of interpersonal relations; is it really possible to have the same set of ethical principles guiding every relationship? Furthermore, Weber argues, through a set of questions, that the ethical evaluations should consider methods used rather than sole intentions. Weber posits the question:

Should it really matter so little for the ethical demands on politics that politics operates with very special means, namely, power backed up by violence?

Instead of offering a dichotomous interpretation of the moralization of violence, Weber advocates for the readers to think critically about violence. After his set of questions, he references the Sermon on the Mount: ‘All they that take the sword shall perish with the sword’.

Weber utilizes the biblical story of the Sermon on the Mount to highlight the stark differences between the uncompromising and absolute demands of the gospel’s ethic and the pragmatic efforts inherent in the realm of politics. The three examples of these differences mentioned involve the politician endorsing various practices that appear antithetical with the Sermon on the Mount: supporting taxation (including confiscatory taxation and out-right confiscation), legitimizing the striking another, and imposing constraints love. (The last two can be considered one and the same)

The evangelical word is without question: “give what thou hast — absolutely everything.” Yet, the politician upholds and advocates for taxation, regulating all; this difference rings true today where poorer individuals face a growing burden of taxation, disproportionately favoring the affluent members of society. Furthermore, consider the rule: “turn the other cheek.” This rule is absolute, yet the politician regularly support war efforts in attempt to maintain their legitimacy and a nation’s honor. Additionally, when Jesus preaches an ethic of love that is unconditional, the politician frequently counters this point through an inverse proposition: ‘thou shalt resist evil by force.’

Weber also discusses the necessary of truthfulness in politics. He discusses the imperative of revealing all documents, even if these documents blame one’s country. However, disclosure has the ability to be one-sided, causing even more problems. Therefore, Weber concludes that, within politics, there needs to be the possibility of unbiased investigations.

Weber continues:

We must be clear about the fact that all ethically oriented conduct may be guided by one of two fundamentally differing and irreconcilably opposed maxims: conduct can be oriented to an ‘ethic of ultimate ends’ or to an ‘ethic of responsibility.’

To clarify, Weber states that an ethic of ultimate ends does not entail irresponsibility nor does an ethic of responsibility entail the best results. From my understanding, this mirrors the difference between Kantian ethics and utilitarianism.

Ethic of ultimate ends: This involves taking action based on one’s principles, regardless of the consequences. The ethic of ultimate ends is akin to religion whereby individuals trust that their actions are morally correct — regardless of the outcome — and the results are left to a higher, usually metaphysical, authority.

Ethic of responsibility: This requires individuals to consider how their actions will manifest into future consequences. These individuals feel that the results of their actions are purely their burden to carry; they feel accountable for the results of their actions.

Weber is not making a claim that one type of ethic is better than the other. Instead, he is attempting to conceptualize the role of ethics in politics.

So… what is the mean of politics?

“The decisive means for politics is violence.”

Evidently, there exists a tension between means and ends. We see this in the context of those advocating for revolution. Though many die in the process of revolution, revolutionaries are willing to prolong the war if it offers a successful end result: “they are willing to face ‘some more years of war.’”

The ethic of ultimate ends seems to face a contradiction: “an ethic of ultimate ends suddenly turns into a chiliastic prophet.” For example, those who initially preached love against violence, perhaps by following God’s law, “now call for the use of force for the last violent deed, which would then lead to a state of affairs in which all violence is annihilated.” In this situation, there is a level of difficulty in justifying the means through ends. Weber writes:

If one makes any concessions at all to the principle that the end justifies the means, it is not possible to bring an ethic of ultimate ends and an ethic of responsibility under one roof or to decree ethically which end should justify which means.

At any rate, Weber discusses the roles of various religions and how their presence ensures that there will always be a debate about how to structure ethics. “Anyone who fails to see this,” Weber says, “is, indeed, a political infant.” He notes that all religions have grappled with the struggle of theodicy: the notion that an omnipotent and benevolent deity can peacefully coexist with an irrational world full of suffering; various religious doctrines have been crafted as a response to theodicy.

*Note: This discussion of various religious continues for a few paragraphs. I will not analyze all the small details of each religious sect Weber mentions. However, I do find it interesting that Weber cites Kautaliya Arthasastra, an Ancient Indian Sanskrit that he compares to a “really radical ‘Machiavellianism’”. Weber explicates, “In contrast to [the Kautaliya Arthasastra], Machiavelli’s The Prince is harmless.”

Regardless, all religions have struggled with the legitimacy of violence as a means in politics.

Weber states:

It is the specific means of legitimate violence as such in the hand of human associations which determines the peculiarity of all ethical problems of politics.

Yet, it must be noted that the utilization of violence as a means does not come without its consequences. If a leader decides they want to ‘make the world better’, they employ the means of violence to achieve their goal. However, the leader requires a following, or what Weber terms “a human ‘machine’”. Additionally, individuals are not willing to impose violence upon another without an award: “the external rewards are adventure, victory, booty, power, and spoils.” Yet, many individuals, even if they were initially fighting for the cause, tend to only fight for themselves and their interests.

With all leaders, their following fades away:

The crusading leader and the faith itself fade away, or, what is even more effective, the faith becomes part of the conventional phraseology of political Philistines and banausic technicians.

Engaging in Politics

Finally, Weber ends with an analysis regarding the paradoxical nature of engaging in politics.

Whoever wants to engage in politics at all, and especially in politics as a vocation, has to realize these ethical paradoxes … The great virtuosi of acosmic love of humanity and goodness, whether stemming from Nazareth or Assisi or from Indian royal castles, have not operated with the political means of violence.

No religion or philosophy of peace have operated within the means of violence. Therefore:

He who seeks the salvation of the soul, of his own and of others, should not seek it along the avenue of politics, for the quite different tasks of politics can only be solved by violence.

Weber isolates that whether one follows an ethic of responsibility or an ethic of ultimate ends, one is situated in a losing position. Following an ethic of responsibility disrupts the ‘salvation of the soul’ because one is striving for political power through the means of violence. In this case, one must take responsibility for their infliction of violence. On the other hand, an ethic of ultimate ends insists that one does not bear responsibility for the consequences of their own actions. Damned if you do, damned if you don’t.

However, we must ask ourselves if there is a way to merge these ethics, rather than viewing them as diametrically opposed. Weber “politics is made with the head,” but he makes clear that politics “is certainly not made with the head alone.” Because of this, Weber encourages a supplementary approach to ethics whereby individuals hold deep, principled beliefs (ultimate ends) but also hold themselves accountable for the consequences of their actions (responsibility). Only in this view can there exist a genuine person who can have the calling to engage in politics.

— —

To conclude, Weber uses Shakespeare’s Sonnet 102 as a metaphor to explain the fleeting nature of individuals’ enthusiasm of engaging in politics. Sonnet 102 is about the nature of love in springtime. Yet, Weber, rather bitterly, states:

Not summer’s bloom lies ahead of us, but rather a polar night of icy darkness and hardness, no matter which group may triumph externally now.

This metaphor illustrates Weber’s apprehension concerning the state of politics during his time and his anticipation of the future trajectory of politics.

Engaging in politics is a gradual and challenging process. Yet, history has confirmed time and time again that individuals “would not have attained the possible unless …. [individuals] had reached out for the impossible.” The individuals entering politics must be resilient, confident, and committed — anything else is a failure. Weber eloquently encapsulates this point in the concluding sentence of Politics as a Vocation:

Only he who in the face of all this can say ‘In spite of all!’ has the calling for politics.

— —

Citation:

- H.H. Gerth and C. Wright Mills (Translated and edited), From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology, pp. 77-128, New York: Oxford University Press, 1946.

Leave a Reply