The politics of death

Necropolitics stands out as a contemporary philosophical masterpiece, exploring the intricate relationship between sovereignty and death. In this blog post, I aim to examine Achille Mbembe’s Necropolitics and offer insightful analysis on the topic.

**Citation Note: Full citation provided at the end of this post

Introduction

Achille Mbembe’s Necropolitics commences with the idea that sovereignty “resides, to a large degree, in the power and the capacity to dictate who may live and who must die” (11). It is essential to bear in mind that power is always exercised. Therefore, “to exercise sovereignty is to exercise control over mortality and to define life as the deployment and manifestation of power” (12). Mbembe draws from Michel Foucault’s theorization of biopower to reach this conclusion; biopower is “that domain of life over which power has taken control” (12).

As the sovereign is predicated from the right to kill, there is no question that war is utilized as “a means of achieving sovereignty as a way of exercising the right to kill” (12). In this sense, Mbembe begins his article, Necropolitics, by “imagining politics as a form of war”, where he posits a crucial question: “What place is given to life, death, and the human body (in particular the wounded or slain body)?” (12).

Politics, the Work of Death, and the “Becoming Subject”

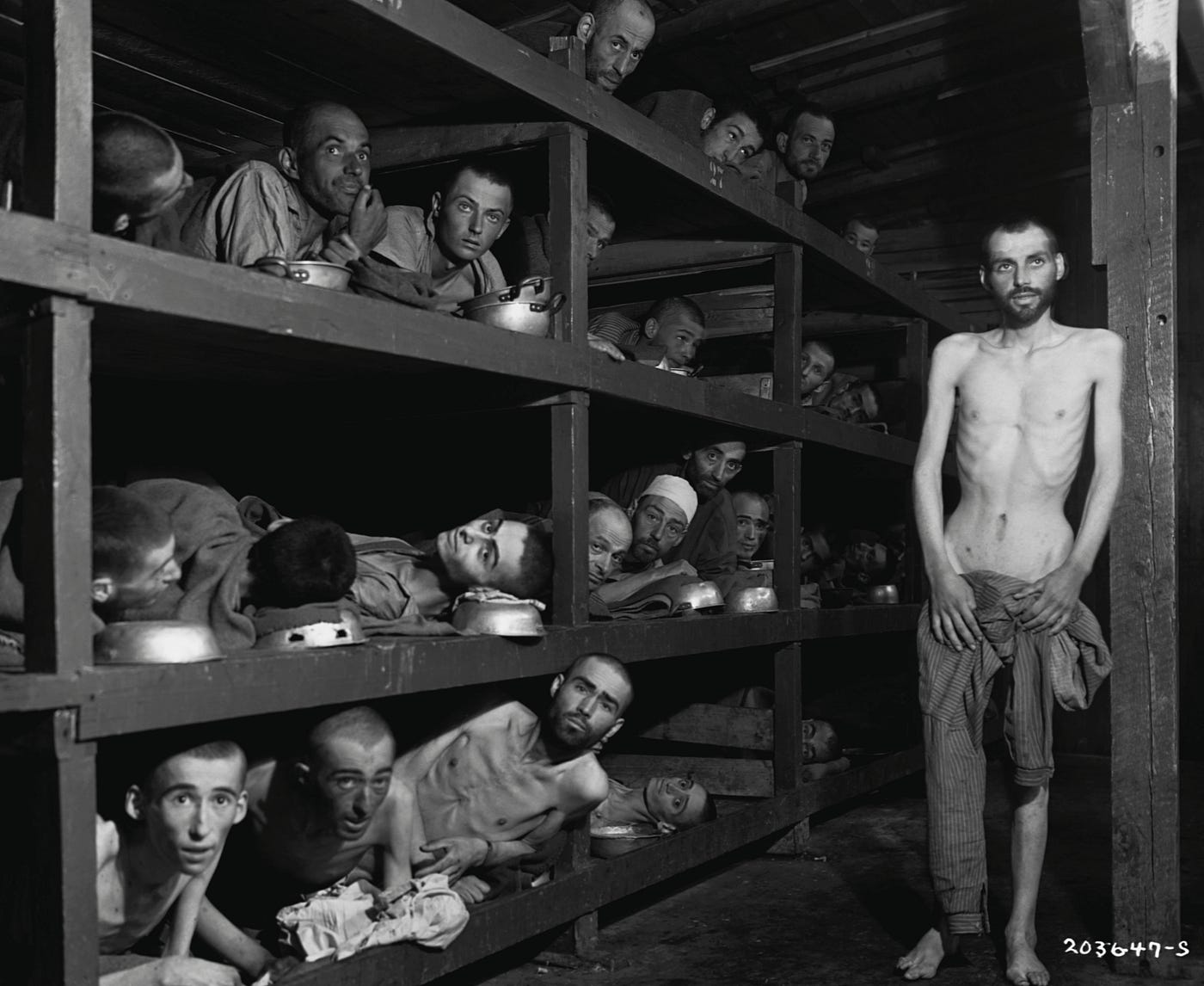

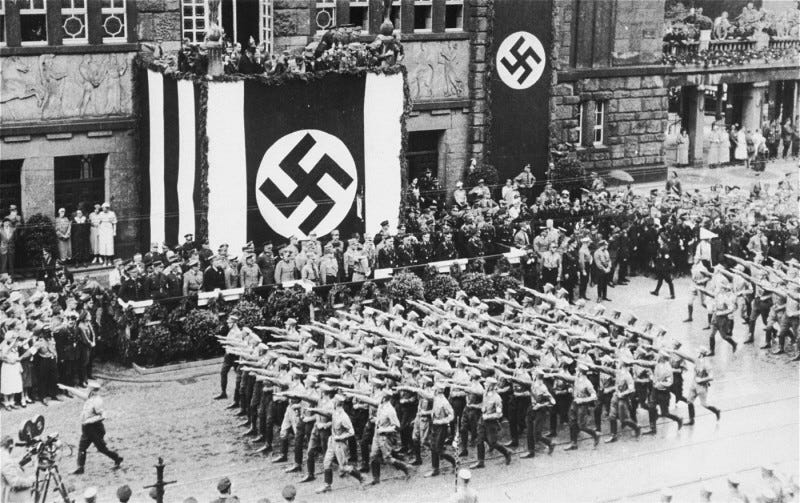

Carl Schmitt, a political theorist, is known for his theorization of the “state of exception” whereby states are able to suspend the normal legal and constitutional orders due to an extraordinary sitution or circumstance. This has been discussed heavily in the context of Nazism, particularly with concentration camps. Mbemebe writes:

The death camps in particular have been interpreted variously as the central metaphor for sovereign and destructive violence and as the ultimate sign of the absolute power of the negative. (12)

Mbembe cites Hannah Arendt who states:

There are no parallels to the life in the concentration camps. Its horror can never be fully embraced by the imagination for the very reason that it stands outside of life and death. (12)

The inhabitants of the concentration camps were stripped of any and all individual rights. Despite being living biophysical bodies, the Jewish peoples were already considered dead in the camps. To use a term from Giorgio Agamben, the inhabitants of the concentration camps were reduced to ‘bare life.’ That is to say, using the language of Giorgio Agamben, the camps were “the place in which the most absolute conditio inhumana ever to appear on Earth was realized” (12). Yet, because of the political-juridical organization of the camp, “the state of exception ceases to be a temporal suspension of the state of law” (12). Mbembe states:

According to Agamben, [the state of exception] acquires a permanent spatial arrangement that remains continually outside the normal state of law. (12–13)

To put simply, the state of exception is not merely a temporary suspension of the law; it holds the potential to become permanent. The state of exception undergoes its own transformation.

Mbembe utilizes this transformation of the state of exception to conclude the origin of sovereignty — or at least to discover a myriad of elements that constitute sovereignty. Mbembe says:

I start from the idea that modernity was at the origin of multiple concepts of sovereignty — and therefore of the biopolitical. (13)

Essentially, Mbembe is proposing an examination of how the state of exception transforms over time, allowing for a historical analysis of the diverse elements that constitute the notion of sovereignty; this is especially true within the context of biopolitics where one can properly analyze the historical developments of the regulation of bodies. Mbembe continues:

My concern is those figures of sovereignty whose central project is not the struggle for autonomy but the generalized instrumentalization of human existence and the material destruction of human bodies and populations. (14)

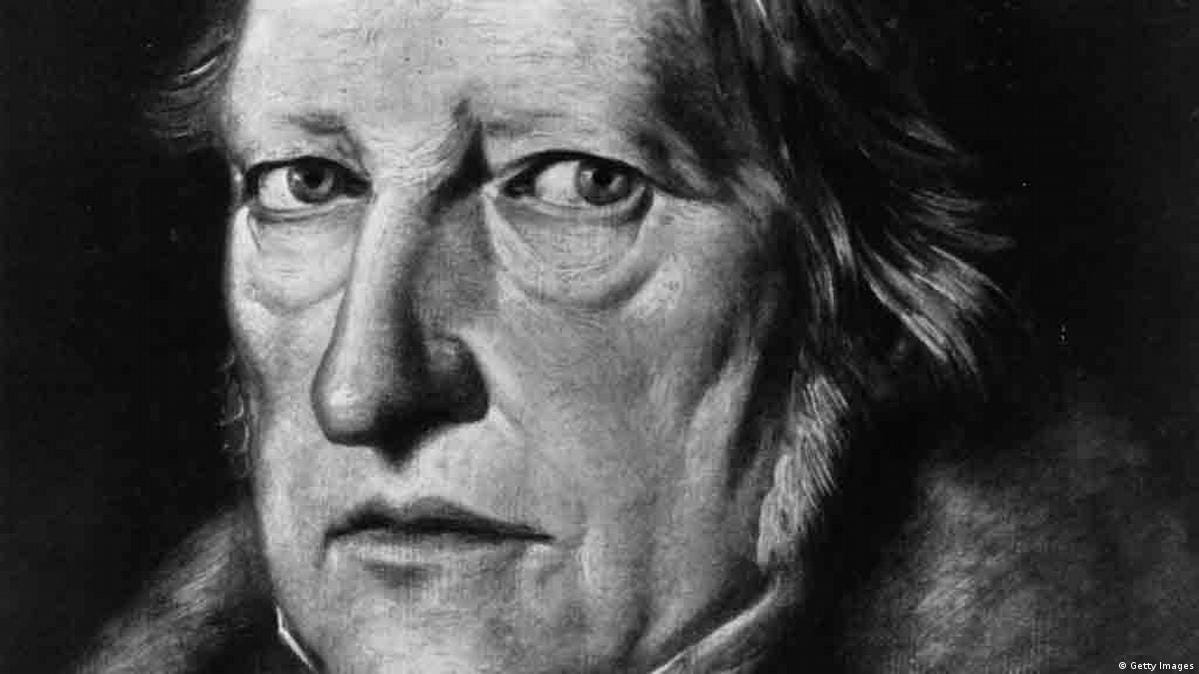

In order for Mbembe to commence his analysis of death in relation to sovereignty, he starts by highlighting the distinctions in the perspectives on death held by philosophers Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel and Georges Bataille. To begin with Hegel:

Hegel’s account of death centers on a bipartite concept of negativity. (14)

To conceptualize Hegel’s account of death, we must first analyze his bipartite concept of negativity. On one hand, Hegel argues that humans negate or oppose nature; that is to say, human efforts modify the natural world around them to fit their needs. On the other hand, humans, having negated nature, engage in work and struggle; this entails the continuation of molding the natural world to fit human needs while encountering obstacles along the way. Simply put: the bipartite concept of negativity explains that humans negate aspects of their environment and engage in transformative activities (like work and struggle) to continuously reshape their environment. Mbembe continues explaining Hegel’s analysis of death:

In transforming nature, the human being creates a world; but in the process, [the human being] also is exposed to [their] own negativity. (14)

Through humans’ creation of the world and environment around them, they are exposed to their own negativity. The confrontation of death, for Hegel, is intrinsically linked to humans negating their environment. However, Hegel argues that this confrontation of death allows individuals to truly become subjects. In other words, when humans move beyond their natural, animalistic state, by reshaping the environment to their needs, they become self-conscious entities. “According to Hegel,” Mbembe writes, “in [the risks of negating nature] the ‘animal’ that constitutes the human subject’s natural being is defeated” (14).

To sum up Hegel’s account of death, Mbembe writes:

The human being truly becomes a subject — that is, separated from the animal — in the struggle and the work through which [they confront] death (understood as the violence of negativity).

It is through this confrontation with death that [they are] cast into the incessant movement of history.

Becoming subject therefore supposes upholding the work of death.

(14)

Bataille, on the other hand, “displaces Hegel’s conception of the linkages between death, sovereignty, and the subject in at least three ways” (15).

First, he interprets death and sovereignty as the paroxysm of exchange and superabundance — or, to use his own terminology: excess. (15)

For Bataille, life and death are fundamentally intertwined, operating through the logics of exchange. Unlike Hegel’s perspective where life is viewed in complete opposition to death, Bataille finds life and death to exists in a constant state of exchange. Rather than viewing death as the loss of something, Bataille views death as a luxurious and exuberant expression of life. On this first point, Mbembe writes:

Even more radically, Bataille withdraws death from the horizon of meaning.

This is in contrast to Hegel, for whom nothing is definitively lost in death; indeed, death is seen as holding great signification as a means to truth. (15)

Essentially, Hegel finds death to be a means to truth: by confronting one’s mortality, there is a larger truth to their subjectivity. On the other hand, Bataille, finds life and death to be in constant exchange, with no larger meaning generated from this relationship.

To continue:

Second, Bataille firmly anchors death in the realm of absolute expenditure (the other characteristic of sovereignty), whereas Hegel tries to keep death within the economy of absolute knowledge and meaning. (15)

On this point, it should be made clear that Bataille does not view death as an ordinary event by any means; however, Bataille does not find death to pertain to a higher truth. This second point “anchors death in the realm of absolute expenditure” which Mbembe defines as a defining characteristic of sovereignty. Absolute expenditure, the idea of spending and consuming in excess, is a defining characteristic of sovereignty as the sovereign has the capacity to exceed its imposed limits (the state of exception being an example here). And, because death is irreversible, death is intimately tied to the notion of absolute expenditure as concepts of sovereignty rely exercising power over death. Mbembe writes:

Death is therefore the point at which destruction, suppression, and sacrifice constitute so irreversible and radical an expenditure — an expenditure without reserve — that they can no longer be determined as negativity.

Death is therefore the very principle of excess — an anti-economy.

Hence the metaphor of luxury and of the luxurious character of death.

(15)

This analysis by Mbembe isolates that, unlike Hegel’s conception of death, Bataille does not find death to be rooted as a negativity. Rather, death is the principle of excess. In traditional economic terms, resources are considered valuable in their utility or exchange value. Yet, death, as something irreversible, is a spending of resources (specifically life), without the expectation of something in return. Death, for Bataille, is contrary to the principle of conservation and accumulation that defines traditional economics. Furthermore, death does not appear to have a practical or utilitarian purpose, not fitting into a rational framework dealing with logics of exchange.

To continue:

Third, Bataille establishes a correlation among death, sovereignty, and sexuality.

Sexuality is inextricably linked to violence and to the dissolution of the boundaries of the body and self by way of orgiastic and excremental impulses.

(15)

Here, Bataille isolates sexuality as being intricately connected to violence and “the dissolution of the boundaries of the body.” The reference to ‘orgiastic and excremental impulses’ is Bataille describing the intensity of sexuality and how sexuality is inextricably linked to the “two major forms of polarized human impulses — excretion and appropriation — as well as the regime of the taboos surrounding them” (15). Therefore, the correlation between death, sovereignty, and sexuality is present through the dissolution of boundaries upon the biophysical body, particularly through excretion and appropriation.

So, for Bataille, what is sovereignty? Mbembe writes:

For Bataille, sovereignty therefore has many forms.

But ultimately it is the refusal to accept the limits that the fear of death would have the subject respect.

(16)

According to this statement, Bataille acknowledges that sovereignty manifests in a myriad of ways. However, there is an essential element to sovereignty, as conceptualized by Bataille, which is the refusal to accept limits. From what we’ve analyzed so far:

- Sovereignty refuses to accept limitations upon itself: this is shown through the state of exception.

- Sovereignty refuses to accept limitations upon death: this is shown through the sovereign dictating who must live and who must die.

Fear of death as a concern for subjects serves as a particular limit. This fear of death results in the imposition of constraints upon individuals. While individuals who fear death typically respect certain limits or boundaries, Bataille’s concept of sovereignty requires the rejection of limits, allowing the sovereign to defy or reject limits upon death.

To conclude on Bataille’s view of sovereignty, Mbembe states:

The sovereign world, Bataille argues, “is the world in which the limit of death is done away with. Death is present in it, its presence defines that world of violence, but while death is present it is always there only to be negated, never for anything but that. The sovereign,” he concludes, “is he who is, as if death were not. . . . He has no more regard for the limits of identity than he does for limits of death, or rather these limits are the same; he is the transgression of all such limits.” (16)

Biopower and the Relation of Enmity

Foucault’s theorization of biopower is one where “the mechanisms of biopower are inscribed in the way all modern states function” (17). We must remember that Foucault’s biopower deals with death as the right to kill compliments the sovereign’s organization of life within its bounds. Mbembe writes:

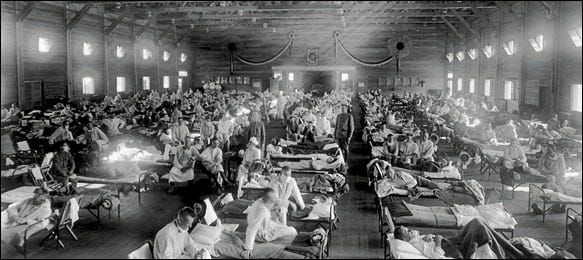

According to Foucault, the Nazi state was the most complete example of a state exercising the right to kill.

This state, he claims, made the management, protection, and cultivation of life coextensive with the sovereign right to kill.

(17)

The Nazi state relied on a political enemy, an organization of war — which exposed its own citizens to conflict — and the right to kill. In this manner, the Nazi state “became the archetype of a power formation that combined the characteristics of the racist state, the murderous state, and the suicidal state” (17). The conflation of racism, murder, and suicide is unique to the Nazi state.

What is of importance here is that the creation of the other necessary for biophysical elimination to secure one’s life and security is a necessary aspect of sovereignty:

The perception of the existence of the Other as an attempt on my life, as a mortal threat or absolute danger whose biophysical elimination would strengthen my potential to life and security — this, I suggest, is one of the many imaginaries of sovereignty characteristic of both early and late modernity itself. (18)

The strive for security — or at least the propagation of the Other in order to strive for security — results in the dehumanization of particular bodies. And, these bodies, for the sovereign, are necessary for extermination as the sovereign seeks to disrupt the limitations imposed upon (by) death and the body. Instruments of governmentality seek to make death as dehumanizing and efficient as possible.

The gas chambers and the ovens were the culmination of a long process of dehumanizing and industrializing death, one of the original features of which was to integrate instrumental rationality with the productive and administrative rationality of the modern Western world (the factory, the bureaucracy, the prison, the army). Having become mechanized, serialized execution was transformed into a purely technical, impersonal, silent, and rapid procedure. (18; emphasis mine)

In a context in which decapitation is viewed as less demeaning than hanging, innovations in the technologies of murder aim not only at “civilizing” the ways of killing. They also aim at disposing of a large number of victims in a relatively short span of time. At the same time, a new cultural sensibility emerges in which killing the enemy of the state is an extension of play. (19; emphasis mine)

Because politics is a war that decides who lives and who dies, terror is, therefore, a necessary part of politics. For Mbembe, terror as part in parcel with politics was best seen during the French Revolution:

During the French Revolution, terror is construed as an almost necessary part of politics … Terror thus becomes a way of marking aberration in the body politic, and politics is read both as the mobile force of reason and as the errant attempt at creating a space where “error” would be reduced, truth enhanced, and the enemy disposed of. (19)

At any rate, Mbembe continues by discussing the structure of the slave planation. He defines the plantation as a “paradoxical figure of the state of exception” (21). There are two paradoxes that Mbembe states:

On the first paradoxical element, “the humanity of the slave appears as the perfect figure of a shadow” (21). The condition of the slave results from the loss of three statuses: “loss of a ‘home,’ loss of rights over his or her body, and loss of political status” (21). Essentially, despite the slave being a living biophysical entity, the triple loss that the slave experiences positions them into a site of social death whereby they are subject to a state of absolute domination. And, “the slave is […] kept alive but in a state of injury” (21). The slave is an instrument of labor, occupying a price; and, the slave is a property, the slave occupies a value. Because the labor of the slave is necessary for the functioning of the plantation, the slave exists in a state of injury. Ultimately, the slave is not a suitable subject for life because they exist in a site of social death, and the slave is not a suitable subject for death because their labor is necessary.

On the second paradoxical element, “in spite of the terror and the symbolic sealing off of the slave, he or she maintains alternative perspectives toward time, work, and self” (22). Though the slave is treated as if their existence is reduced to a mere instrument of labor, the slave is “nevertheless […] able to draw almost any object, instrument, language, or gesture into a performance and then stylize it” (22). In this paradox of the state of exception, the slave, seemingly denied agency, has the capacity to showcase creative expression.

The debate about the technologies that led to Nazism, whether stemming from the plantation or the colony, or Foucault’s argument that Nazism was a result of existing technologies of law found in Western European biopolitical measures (such as health regulations or eugenics), is largely irrelevant. However:

A fact remains, though: in modern philosophical thought and European political practice and imaginary, the colony represents the site where sovereignty consists fundamentally in the exercise of a power outside the law (ab legibus solutus) and where “peace” is more likely to take on the face of a “war without end.” (23)

This quote from Mbembe aligns with Schmitt’s definition of sovereignty:

On the one hand, to kill or to conclude peace was recognized as one of the preeminent functions of any state.

It went hand in hand with the recognition of the fact that no state could make claims to rule outside of its borders.

But conversely, the state could recognize no authority above it within its own borders.

On the other hand, the state, for its part, undertook to “civilize” the ways of killing and to attribute rational objectives to the very act of killing.

(23; emphasis mine)

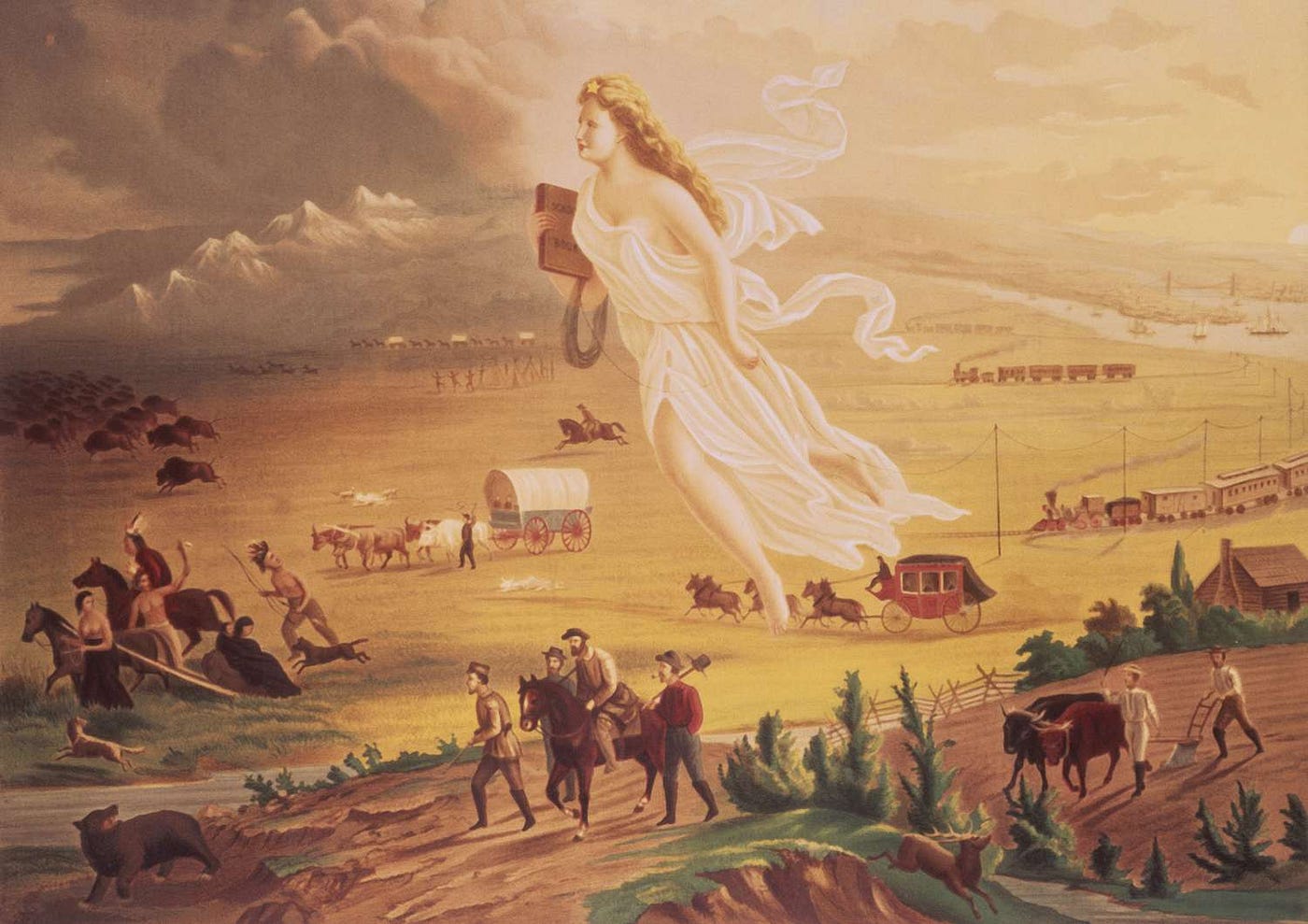

Mbembe proceeds to analyze settler colonialism and the operationalization of sovereignty upon indigenous societies. The sovereign right to kill is most pronounced in the context of colonialism because the colonized are deemed to be outside of humanity. “In the eyes of the conqueror, savage life is just another form of animal life, a horrifying experience, something alien beyond imagination or comprehension” (24; emphasis mine). Drawing from Arendt, Mbembe notes that the oppression of the native is less about the color of their skin, but that they behave like a part of nature compared to the colonists:

Nature thus remains, in all its majesty, an overwhelming reality compared to which they appear to be phantoms, unreal and ghostlike.

The savages are, as it were, “natural” human beings who lack the specifically human character, the specifically human reality, “so that when European men massacred them they somehow were not aware that they had committed murder. (24)

As with any efforts of colonization, there is a particular jurisdiction, albeit arbitrary, that the colonizers claim to have control over. “Space was therefore the raw material of sovereignty and the violence it carried with it” (26). Therefore, colonizers have the capacity to define the terms of life and death within the bounds of their occupation, “relegating the colonized into a third zone between subjecthood and objecthood” (26).

Sovereignty means the capacity to define who matters and who does not, who is disposable and who is not. (27)

Furthermore, Mbembe expands upon political philosopher, Frantz Fanon’s, spatialization of colonial occupation and applies it to the Israel-Palestinan conflict. Mbembe highlights “three major characteristics in relation to the working of the specific terror formation I have called necropower” (26; emphasis mine). Throughout this section, he references Eyal Weizman, an Israeli architect, who analyzes spatialization in the context of sovereignty.

So… what are the three major characteristics of terror in relation to the working of the specific terror formation that is defined as necropower?

- The first characteristic concerns “the dynamics of territorial fragmentation, the sealing off and expansion of settlements” (27–28). Mbembe states that “the objective of this process is twofold: to render any movement impossible and to implement separation along the model of the apartheid state” (28).

In the context of territorial fragmentation, space is divided into organized cells with various internal borders. This does not just apply to land as “colonial occupation operates through schemes of over- and underpasses, a separation of the airspace from the ground” (28). Territorial fragmentation is necessary for necropower as maintaining the high ground offers effectiveness through ‘panoptic fortification’ that allows the sovereign to maintain the fragmentation of space.

- The second characteristic concerns “a splintering form of colonial occupation” that is “characterized by a network” (28). This network pertains to various infrastructural technologies defined by “fast bypass roads, bridges, and tunnels that weave over and under one another” (28).

In the context of splintering occupation and infrastructure, space is policed and organized by means of infrastructural technologies. “The battlegrounds are not located solely at the surface of the earth. The underground as well as the airspace are transformed into conflict zones” (29). Splintering occupation and infrastructure is necessary to restrict movement and splinter communities of people. In this manner, “killing becomes precisely targeted” (29).

Critical to these techniques of disabling the enemy is bulldozing: demolishing houses and cities; uprooting olive trees; riddling water tanks with bullets; bombing and jamming electronic communications; digging up roads; destroying electricity transformers; tearing up airport runways; disabling television and radio transmitters; smashing computers; ransacking cultural and politico-bureaucratic symbols of the proto-Palestinian state; looting medical equipment.

In other words, infrastructural warfare.

(29)

- The third characteristic concerns “a concatenation of multiple powers: disciplinary, biopolitical, and necropolitical” (29). Mbembe writes that “the combination of the three allocates to the colonial power an absolute domination over the inhabitants of the occupied territory” (29).

War Machines and Heteronomy

In the era of globalization, war “force the enemy into submission regardless of the immediate consequences, side effects, and ‘collateral damage’ of the military actions” (31). Because of this, Mbembe writes that contemporary warfare is analogous to the “warfare strategy of the nomads” (31).

Though the sovereign initiates war, “alongside armies have […] emerged what […] we could refer to as war machines” (32). Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari introduced the concept of the war machine in their book A Thousand Plateaus. Mbembe describes war machines as being “made up of segments of armed men that split up or merge with one another depending on the tasks to be carried out and the circumstances” (32). The merging of segments are “polymorphous and diffuse organization” defined by their “capacity for metamorphosis” (32). At times:

The state may, of its own doing, transform itself into a war machine.

It may moreover appropriate to itself an existing war machine or help to create one.

War machines function by borrowing from regular armies while incorporating new elements well adapted to the principle of segmentation and deterritorialization.

Regular armies, in turn, may readily appropriate some of the characteristics of war machines. (32)

Mbembe notes that in contemporary warfare, war is usually “no longer waged between armies of two sovereign states. It is waged by armed groups acting behind the mask of the state against armed groups that have no state but control very distinct territories” (35). However, it must be noted that there are contemporary wars between states.

Of Motion and Metal

Mbembe proceeds to discuss martyrdom and the role of the body as a weapon. The “suicide bomber” is unique in that they do not overtly display a weapon and they appear to be dressed in regular clothes. Therefore, the suicide bomber’s body undergoes a process of transformation:

The candidate for martyrdom transforms his or her body into a mask that hides the soon-to-be-detonated weapon.

Unlike the tank or the missile that is clearly visible, the weapon carried in the shape of the body is invisible.

Thus concealed, it forms part of the body.

It is so intimately part of the body that at the time of detonation it annihilates the body of its bearer, who carries with it the bodies of others when it does not reduce them to pieces.

The body does not simply conceal a weapon.

The body is transformed into a weapon, not in a metaphorical sense but in the truly ballistic sense.

(36)

In the case of the suicide bomber, Mbembe observes that “homicide and suicide are accomplished in the same act… War is the war of body on body (guerre au corps-à-corps)” (37). From the sovereign’s viewpoint, the suicide bomber, by defying the fear of death and simultaneously “closing the door on the possibility of life for everyone” (37), trespasses the boundaries of mortality in a way that challenges conventional perceptions of life and death in the context of warfare.

The body here becomes the very uniform of the martyr. (37)

What is the role of sacrifice in relation to sovereignty?

[Sacrifice] is not simply the absolute manifestation of negativity.

It is also a comedy.

For Bataille, death reveals the human subject’s animal side, which he refers to moreover as the subject’s “natural being.”

(38)

In Bataille’s perspective, sacrifice does not just express pure negativity because it possesses elements of comedy. For Bataille, death reveals the more primal, animalistic aspect of the human subject. Mbembe utilizes Bataille’s analysis to isolate that the confrontation of death ought not exist as a future event, but rather, the confrontation of death occurs while one is alive. Therefore, the individual should be aware of their impending death, experiencing the interplay of death while alive. Bataille says:

In the sacrifice, the sacrificed identifies himself with the animal on the point of death.

Thus he dies seeing himself die, and even, in some sense, through his own will, at one with the weapon of sacrifice.

But this is play!

(38)

Conclusively, the suicide bomber’s sacrificial act is spectacularized, with “no animal to serve as a substitute victim” (38–39). It must be noted that Mbembe is not advocating for individuals to become suicide bombers. Instead, he is analyzing the use of the body in relation to the sovereign. Evidently, the sovereign cannot properly conceptualize the act of the suicide bomber because there is no body to punish: the suicide bomber’s body is a weapon, with the suicide bomber transgressing the limitations of death while living.

Mbembe concludes this section by stating:

For death is precisely that from and over which I have power. But it is also that space where freedom and negation operate. (39)

Conclusion

Ultimately, necropolitics is quite groundbreaking in conceptualizing death in relation to sovereignty. Mbembe concludes by summing up Necropolitics:

The essay has also outlined some of the repressed topographies of cruelty (the plantation and the colony in particular) and has suggested that under conditions of necropower, the lines between resistance and suicide, sacrifice and redemption, martyrdom and freedom are blurred. (40)

— —

Citation:

- Mbembe, Achille. Necropolitics: Public Culture, Volume 15, Number 1, Winter 2003, pp. 11–40 (Article)

Leave a Reply