Examining the Due Process Model and the Crime Control Model

**Citation Note: Full citation provided at the end of this post

Jurisprudential Juxtaposition

In order to conceptualize the intricacies of our criminal justice system, one must first consider two different jurisprudential theories: natural law and legal positivism. On one hand, natural law theorists believe that morality is woven into the fabric of human nature. On the other hand, legal positivists propagate the notion that morality is operationalized and found within institutions. Although both schools of thought differ in their measures of reliability and efficiency in the judicial system, they both agree on the fundamental premise that our criminal justice system ought to be, to an extent, reliable and efficient (both if possible).

Regardless of what each model prioritizes, there are tensions present between due process and policies that seek to maintain public safety. Through a jurisprudential analysis of the complexities that undergird both due process and policies that attempt to ensure public safety, one can successfully analyze the nuanced intricacies that underpin the various models of our judicial system.

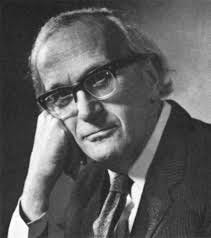

A prominent debate between H.L.A Hart and Lon Fuller isolates both natural law and legal positivism in practice. Hart and Fuller’s debate concerned the moral underpinnings of Nazi Germany’s laws and what the enforcement of a law specifically entails. This debate identified the nuanced complexities embedded within moral structures of institutions. Hart, a legal positivist, believed that the Nazi laws of 1934 were true laws as they were backed by the force of the State (in this case, the Third Reich). Fuller, conversely, believed that the Nazi laws were not true laws due to their overt immorality — whether it be backed by force or not. Thus, this debate plays an important role in analyzing the ethicality of a law and what it means to commit a crime.

Both natural law and legal positivism underlie due process and policies that seek to maintain public safety. Although there are many persuasive arguments surrounding the application of natural law and legal positivism to specific models of the criminal justice system, this blog will argue that there is no single, objectively correct answer. However, this is not to indicate that one philosophical system cannot be better applied to one of the models than the other. I will argue that natural law is much more applicable to the Due Process Model. Conversely, I will argue that legal positivism is better applied to the Crime Control Model. Before a thorough examination of this application takes place, it is necessary to define and explore the Crime Control Model and the Due Process Model.

Herbert Packer, an American law professor, offers a rigorous analysis of the Due Process Model and Crime Control Model. Because of how Packer structured his writing, I will begin by writing about the Crime Control Model. The Crime Control Model believes that regulating criminal conduct is of utmost importance for the functionality of the judicial system. This model believes that failing to prioritize the regulation of criminal conduct necessitates a break within public order leading to “a general disregard for legal controls” (Packer 17). Packer, under this model, states:

The law abiding citizen then becomes the victim of all sorts of unjustifiable invasions of his interests. (17)

Legal positivism operates under this model because it believes that morality is embedded in institutions through laws; the ethicality of said laws are not of importance. However, this model appears to be wildly inefficient as our country does not have the power (nor the resources from the public sector) to apprehend and convict every criminal with appropriate speed. Thus, Packer argues that this process cannot have unnecessary “ceremonious rituals that do not advance the progress of the case” (18). Legal positivism, however, makes up for this inefficiency by relying on the presumption of guilt. Rather than jumping through a litany of hurdles to prove someone guilty, Packer indicates that this model believes in “screening processes operated by police and prosecutors” which are “reliable indicators of probable guilt” (19).

In this manner, Packer describes the Crime Control Model as a “conveyer belt” and the Due Process Model as an “obstacle course” (20).

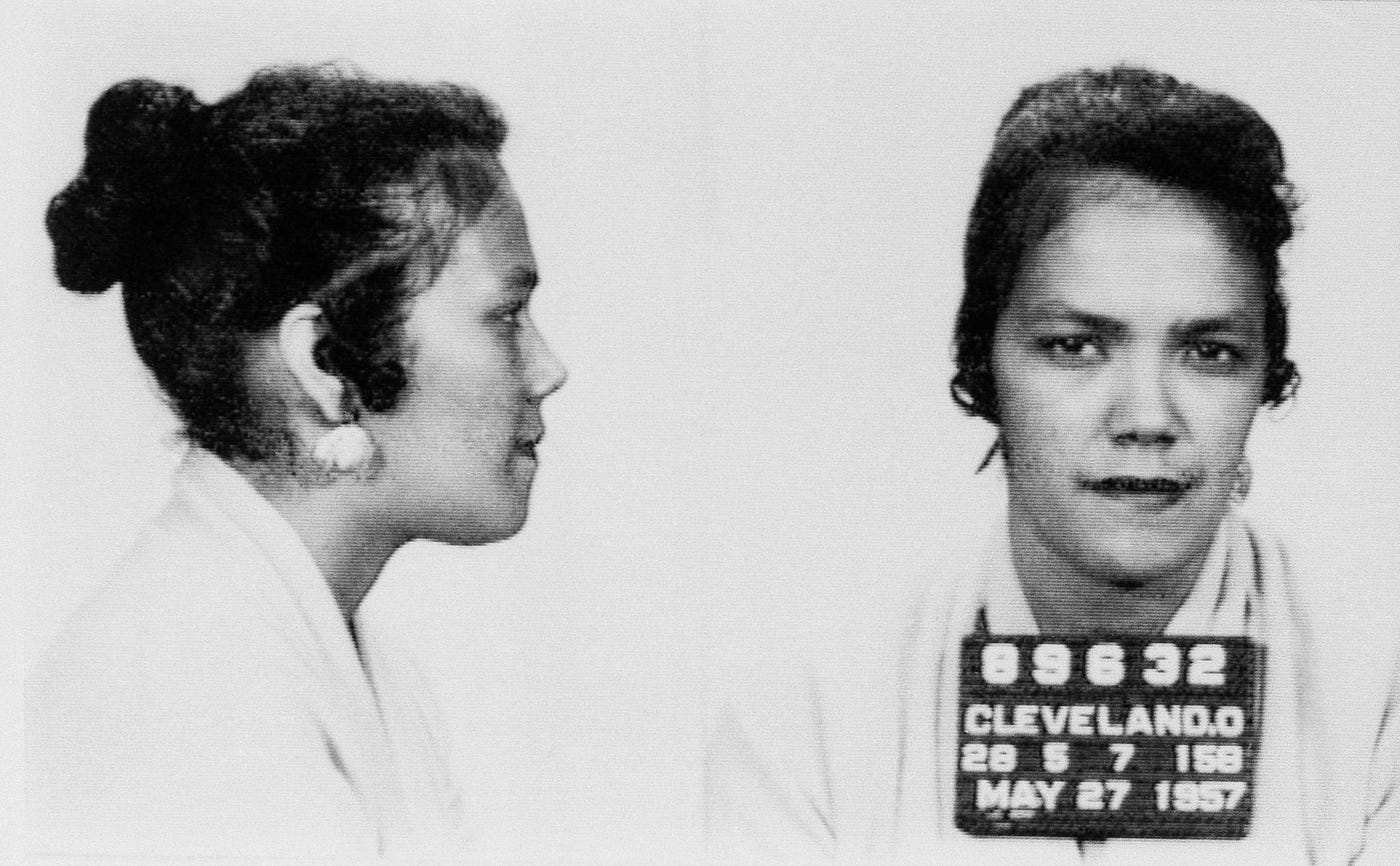

The ruling in Maryland v. King is a perfect example of the Crime Control Model in practice. This legal precedent addressed the inquiry of whether, under the Fourth Amendment, states are allowed to collect DNA samples from individuals who are arrested, but not yet convicted of a crime. In a 5–4 decision, the Court ruled that the collection of King’s DNA, prior to a conviction, was constitutional (Maryland v. King, 569 U.S. 435, 2013). Under the Crime Control Model, the collection of one’s DNA, even if one is not yet convicted of a crime, is necessary to solve unsolved cases or future cases. In fact, King’s DNA was inevitably linked to the DNA of an unsolved rape case which allowed him to be convicted of first-degree rape. Although many have argued that this invasive procedure violated King’s personal liberties (as it is a rarity to see Scalia and Ginsberg agree in their dissent), the Crime Control Model finds the collection of DNA to be of higher importance as it prioritizes the regulation of criminal conduct.

When addressing the issue of individual liberties, it is necessary to discuss the implications of the Due Process Model. According to Packer:

The Due Process Model insists on the prevention and elimination of mistakes to the extent possible. (21–22; emphasis mine)

An excellent illustration of prevalent mistakes in the criminal justice system is evident with individuals confessing to crimes they did not commit or accidentally providing inaccurate information to the police. In a high intense situation, it is incredibly easy to misrepresent facts; for example, imagine a scenario where a robbery unfolds right before your eyes and you are questioned about the color of the robber’s sunglasses, you might unintentionally offer an incorrect answer. Now, imagine if your (accidental) incorrect answer was used to convict an innocent passerby. Therefore, predicating one’s liberties based on accidental, false information is something the Due Process Model directly seeks to avoid.

As the Due Process Model operates, its sole focus is that of protecting the factually innocent. Natural law best applies to due process as this model focuses on the moral implications of human nature and the implications of how our system finds one ‘factually guilty’. Though, this is not to assume that the Due Process Model does not attempt to convict those who are factually guilty.

Ideologically, due process focuses on the structural formation of law rather than a focus on crime control. The reasoning for this is due to the doctrine of legal guilt. Even if all signs point to an individual committing a crime, they are not guilty unless “these factual determinations are made in a procedurally regular fashion” (Packer 22). For example, having qualified authorities coupled with an institution containing obstacles is necessary to definitively declare one guilty. Unlike the Crime Control Model, the Due Process Model finds the loss of one’s liberties to be of the highest ethical importance. While one could argue that due process is grossly inefficient, the Due Process Model rejects efficiency if it comes at the cost of reliability.

An example of the Due Process Model in practice would be the decisions in Miranda v. Arizona and Riley v. California. In Miranda v. Arizona, the Court established one’s Miranda Rights be read to them after having been arrested (384 U.S. 436, 1966). Rather than allowing one to potentially self-incriminate themselves, Miranda Rights notify individuals of their right to remain silent. This aligns with the Due Process Model as individual liberties outweigh the potential conviction of a criminal. Similarly, Riley v. California deals with the question as to whether a warrantless search and seizure of digital contents of a cell phone during an arrest is constitutional. The Court made a unanimous decision stating that this action is fundamentally unconstitutional as it violates the Fourth Amendment’s protection against warrantless searches (Riley v. California, 573 U.S. 373, 2014). Even if illegal information can be obtained from the warrantless search, due process seeks to preserve one’s rights.

Although due process and policies that seek to protect people’s safety seem to be in direct opposition to one another, it should be noted that due process and crime control do contain similarities. In the case of Mapp v. Ohio where a warrantless search led to the finding of illegal pornographic materials, the Court ruled that Mapp could not be tried for the possession of those materials as they were discovered illegally (367 U.S. 643, 1961). In the case of Mapp v. Ohio, the Crime Control Model would not necessarily advocate for one’s home to be ransacked by the police at any given moment; rather, the Crime Control Model argues that if an illegal search discovered an individual possessing illegal items, then the individual should be charged for the possession of these illegal items as it is against the law. On the other hand, the Due Process Model advances the measure of upholding one’s individual right against a warrantless search and seizure, prioritizing one’s individual rights over their possession of illegal materials.

In the context of having the right to a lawyer, many decisions have been made to protect the right to legal counsel — most notably in Gideon v. Wainwright (372 U.S. 355, 1963). Although Gideon grants one a lawyer in a criminal case, one ought not assume that one’s trial is inherently fair. There have been other cases, like Batson v. Kentucky, which have attempted to remedy unfair practices within the legal system. The legal precedent Batson establishes that a jury of one’s peers is necessary to avoid bias. These cases fit neatly into the Due Process Model as they attempt to preserve the individual liberties of a person instead of focusing on proving them guilty. Although a guilty individual may be able to ‘cheat’ the system with these procedures, the Due Process Model finds this to be a better option as the alternative may put an innocent person behind bars.

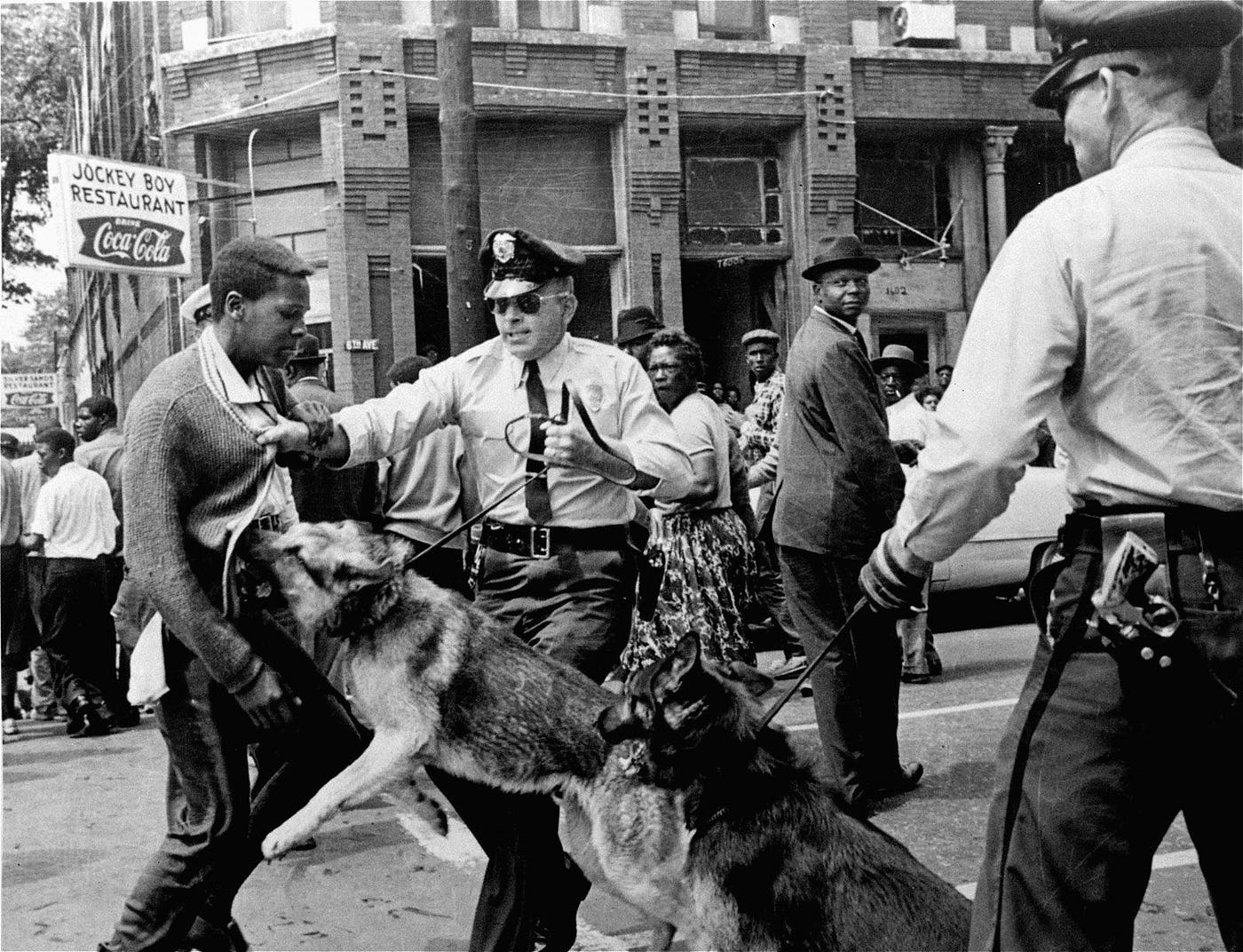

While aspects of the legal system operate under due process, there are aspects of the police state that fall within the Crime Control Model. In the status quo, the police state has been widely criticized for its excessive use of force and the ability to kill someone based on an officer’s discretion of a threat. Joseph Goldstein, writer for The New York Times, cites the Supreme Court’s endorsement of force being evaluated from an officer’s perspective and says the Supreme Court holds that “such encounters ought to be judged from the perspective of a reasonable officer on the scene …” (Goldstein 2016). From the Crime Control Model’s perspective, the officer’s viewpoint is incredibly efficient as it allows cases to go through expeditiously and catch offenders.

While due process and policies that attempt to protect the public’s safety have mainly been applied to legal citizens, Boumediene v. Bush expands this analysis to people who are not U.S. citizens. The decision made in this case was highly politicized as it allowed “aliens detained as enemy combatants in Guantánamo … a constitutional right to challenge their detention” (Dworkin 2008). Ronald Dworkin, a notable professor of jurisprudence, recognizes that American law previously had not recognized people imprisoned abroad as having such rights (2008). Under due process, this decision was made with individuals’ liberties in mind; however, the Crime Control Model finds this decision in Boumediene to be faulty as it potentially allows criminals (in this case, terrorists) to walk freely. Whether it be U.S. citizens or not, the tensions between due process and policies that seek to protect public safety remain relevant.

Notwithstanding the conflicting values with which the two models attempt to govern our criminal justice system, the Crime Control Model and the Due Process Model seek to maintain a relatively stable system. This stability arises from reliability and efficiency, but each model prioritizes reliability and efficiency with differing magnitudes. Both the Crime Control Model and the Due Process Model have their differences which is shown through jurisprudential theories, the legal system, the police state, and various court cases.

As we are dealing with various theories and thinkers, it is important to recognize that no single model resolves all issues, nor can a single model solely apply to one jurisprudential theory. However, through a proper analysis of each model and what undergirds them, we can successfully conceptualize how each model works in practice.

— —

Citations:

- Packer, Herbert. “Criminal Justice: Law and Politics” Article One: “Two Models of the Criminal Process.” 1993.

- Maryland v. King, 569 U.S. 435, 2013. https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/12-207

- Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436, 1966. https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/384/436/

- Riley v. California, 573 U.S. 373, 2014. https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/573/373/

- Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643, 1961. https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/367/643/

- Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 355, 1963. https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/372/335/

- Goldstein, Joseph. “Is Police Shooting a Crime? It Depends on the Officer’s Point of View.” 2016. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/29/nyregion/is-a-police-shooting-a-crime-it-depends-on-the-officers-point-of-view.html

- Dworkin, Ronald. “Why It Was a Great Victory.” 2008. https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2008/08/14/why-it-was-a-great-victory/

Leave a Reply