Revisiting and revising an essay of mine that showcases the brilliance of Foucault’s Discipline and Punish

**Citation Note: Full citation provided at the end of this post

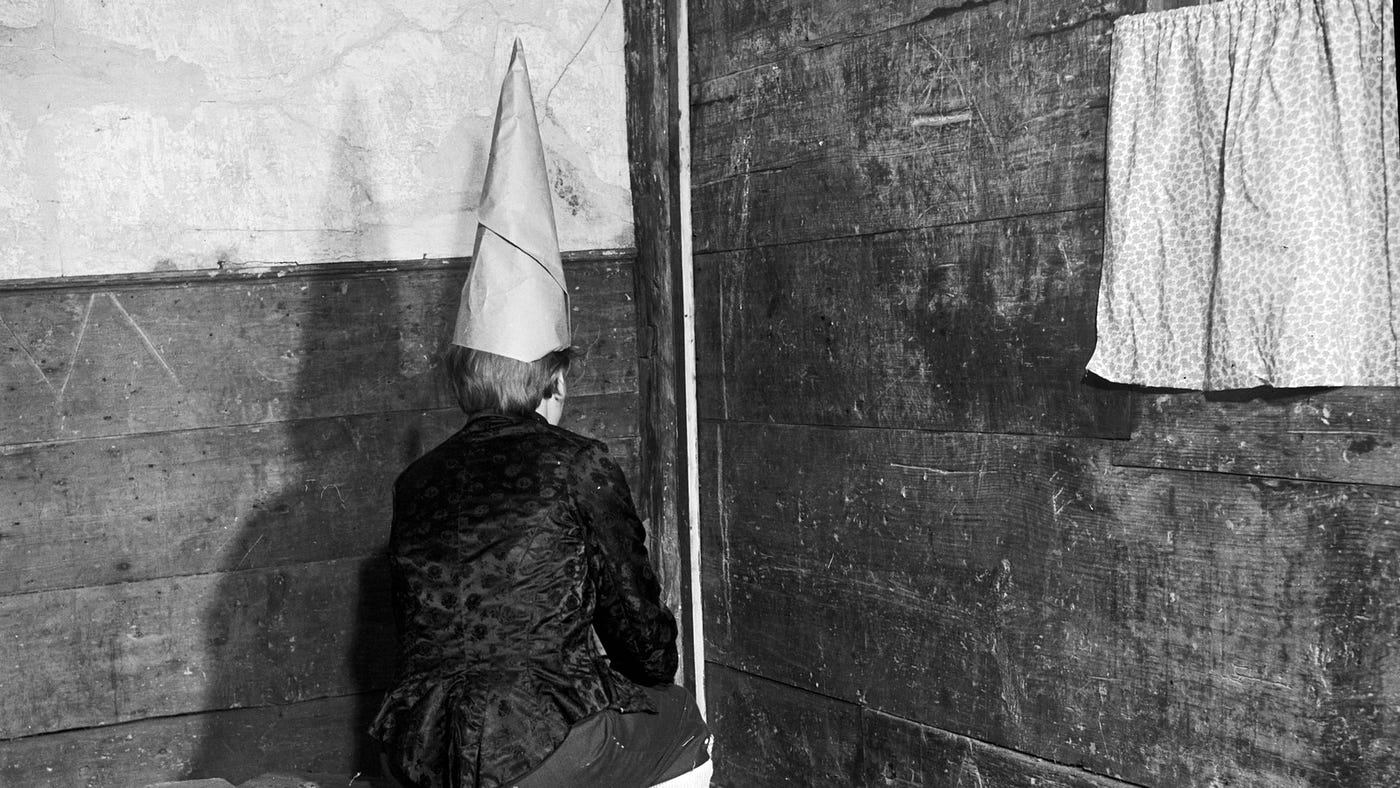

How to Make a Dunce Cap:

I’ve been generous enough to provide the paper. The first step is to take a page from this essay (or glue the edges of multiple pages together to make one large paper) and cut out a semi-circle with scissors. Next, roll the semi-circle into the shape of a cone by bringing the two flat points of the paper to a point of singularity. Finally, glue the sides together and add a colorful ribbon (if you wish to be humane). This is not a simple compact topological space — it is the academic industrial complex.

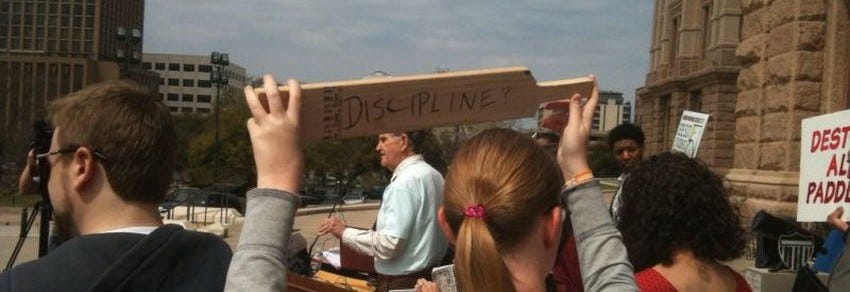

Functioning hierarchically, juridical academics are sadistic:

“Bend over my knee and put your hands behind your back. I’ll grab your hands tightly with one hand while paddling you on the buttocks with the other. Now, place your knuckles on the desk and make them firm, firm enough so I can break them with switches, birches, and rulers. For the sake of humiliation, wear this dunce cap on your head and sit in the corner while the blood from your knuckles drips to the floor.”

This is not corporal punishment as we have been led to believe — it’s corporeal punishment.

The program above must not be interpolated as a simple historicity of disciplinary exercises of power within academic institutions — the State must be creative in its methods of punishment. Michel Foucault is correct in stating that “the soul is the effect and instrument of a political anatomy; the soul is the prison of the body” (30; emphasis mine). The construction of the ‘self’, promulgated by instruments of governmentality, are a limiting force upon the biophysical body.

Political anatomy, as a term of art, is the methodological operation that surgically transplants the organs of governmentality upon the organs of individual bodies to craft State-sanctioned subjectivities. Thusly, humaneness has never existed as the State’s harvesting practices target all organs and explore varying degrees of pain: “they send you here for life, that’s exactly what they’re taking” (Shawshank Redemption, 1994).

Political anatomist, Sigmund Freud, reduces individual organs to representations; he finds the penis-organ representing the Founding Fathers, the vagina-organ representing Lady Liberty, and the anus-organ representing the bureaucracy. In a similar vein, the State, in all its nationalistic imagery, is a systemization of representations. A perplexing thought arises surrounding the representation of organs and government: various sole organ theories, multiple organs of government, and the separation of organs (separation of powers). Although political institutions uphold the State’s ideal subject, notions of humaneness are self-constructed and self-serving. As the State requires the political anatomization of bodies to corporealize its existence, various legal interpretations of the State’s utilization of violence do not change its violent practices of punishment:

- Scalia’s Originalism: organs must be stripped down and tied tightly. The tightness of organs must prevail as sodomy laws prevent “a disruption of the social order” (Lawrence v. Texas): we must constrain organs to a particularized functionalism. All organs must be closed shut or opened by State force; although the organs may hurt, pull the strings on corsets tighter. Extend these logics to the birth of deformed organs (Webster v. Reproductive Health Services and Planned Parenthood v. Casey)

- Dworkin’s Interpretivism: organs must be relieved of some tension but kept in their respective positions. Surely, organs can have multiple uses; however, organ-uses are only accessible to those occupying the position of the citizen-Ideal. Emit a flow or interrupt one, but don’t overstretch as the body is property of the State apparatus. As natural law must be confined through a legal positivist framework, the line between freedom and confinement is completely blurred.

As the State exercises power, organs will always be bound by a string of politics: a gross anatomical power concerned with eradicating difference. “Exercise is that technique by which one imposes on the body tasks that are both repetitive and different, but always graduated” (161). Power, and the exercise of it, is found within all social relations and epistemologies: “it is to be found in military, religious and university practices either as initiation ritual, preparation ceremony, theatrical rehearsal or examination” (161).

Foucault isolates that the exercise of power occurs in various sites and is not solely contained in a State-sanctioned prison; prisons are everywhere, varying in form. Rightfully so, notions of humaneness posited by the State only serve to reify the States’ existence; subjects of the State cannot be treated humanely as freedom is subject to State allowance. Yet, liberal subjects appear to be content with their oppression. As Michel Foucault wrote the preface to Anti-Oedipus, a quote from Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari is necessary: “Why do men fight for their servitude as stubbornly as though it were their salvation?” (Anti-Oedipus, 29).

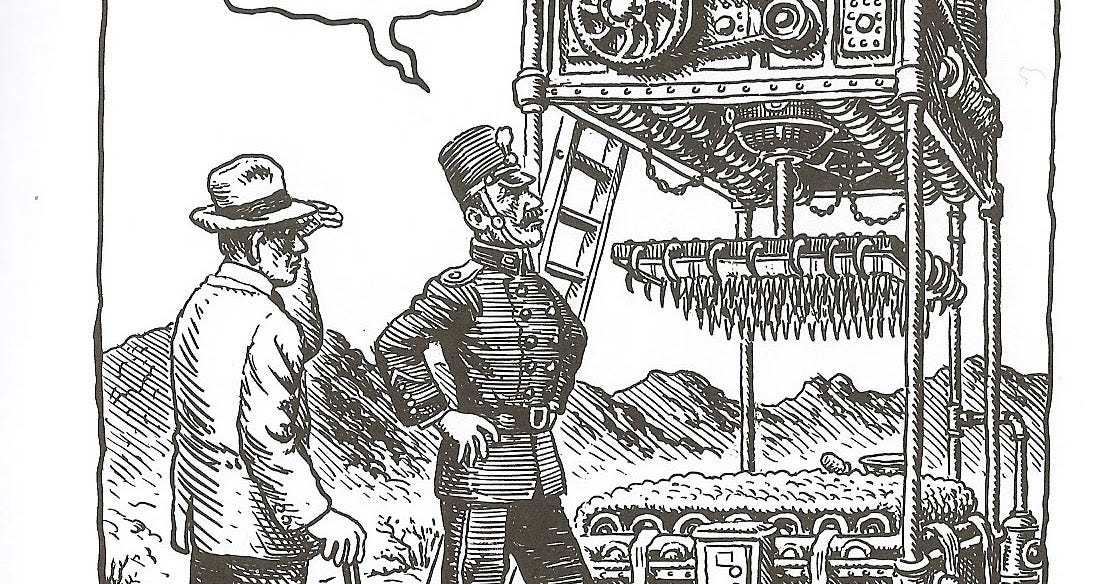

Let us use a literary example from Franz Kafka which brilliantly examines the strength of liberalized populations’ subservience to their oppressors. Kafka’s In the Penal Colony tells a story of the Traveller engaging in a conversation with the Officer, delving into the formidable power wielded by the government. The Officer chillingly reveals the State’s method of imprinting the names of committed crimes onto the flesh of its prisoners. Generally, this would be a simple observation — one commits a crime and gets punished; however, Kafka shows us that prisoners desire this infliction of pain: the Condemned Man is portrayed as an obedient dog that the master “would only have to whistle at the start of the execution for [the Condemned Man] to return” (In the Penal Colony, 1919).

Echoing the sentiment of Foucault, Kafka finds power outside of pure visuality — the State does not need to be physically present in order to police its subjects as subjects are content in policing themselves as they desire their infliction of pain. As the prisoners in Kafka’s novel are subject to death by having their flesh carved into by a technological State apparatus, Kafka notes that “it’s not easy to figure out the inscription with your eyes, but our man deciphers it with his wounds” (In the Penal Colony, 1919)

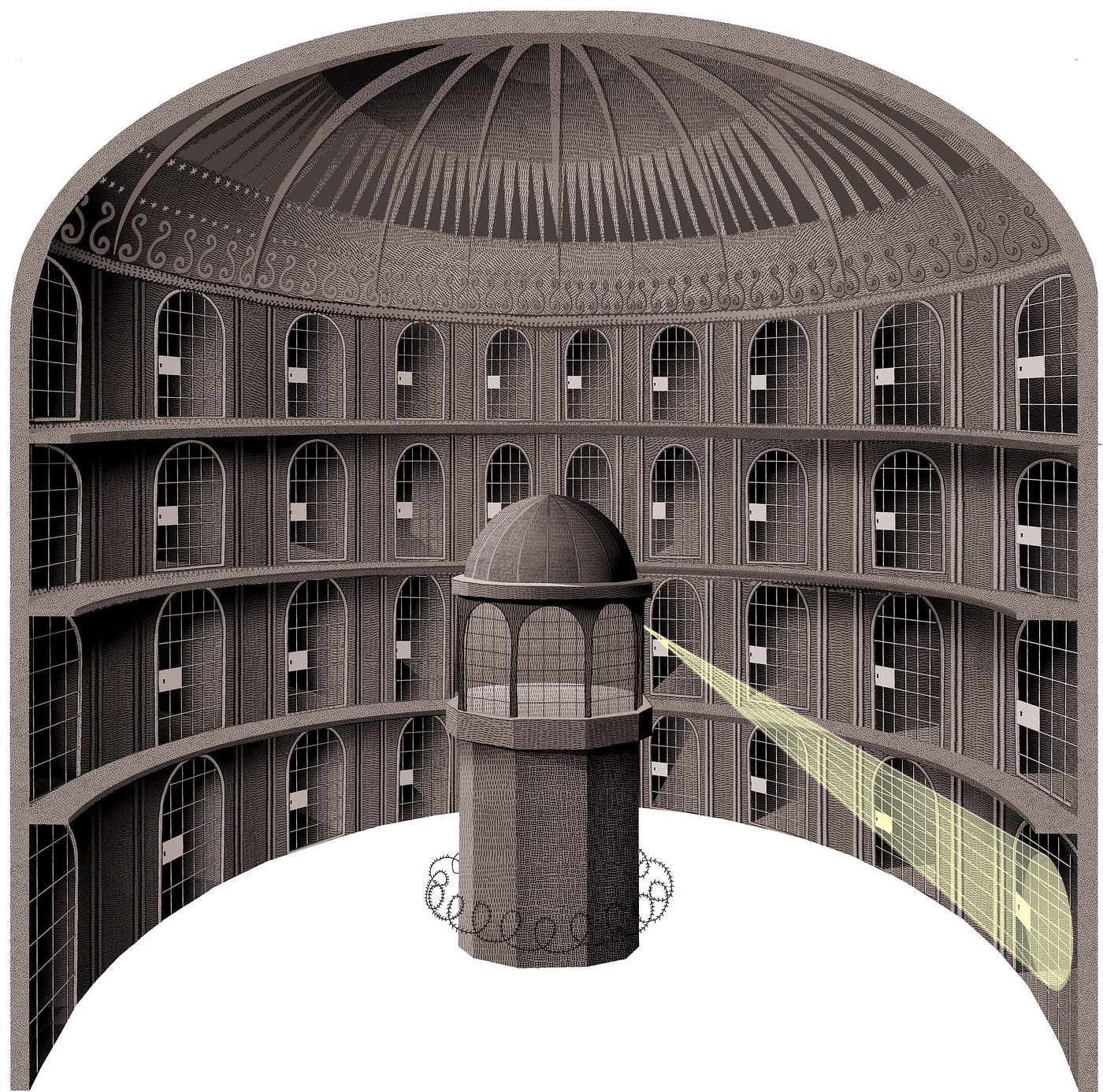

Like the prisoners in Kafka’s penal colony, liberal societies find pleasure in tightening their chains and bowing to bureaucrats. The organs of prisoners are fixed upon a body of power that papier-mâchés itself over natural flows of desire, trapping organs that seek to evolve without constraint. As desire becomes inculcated within power relations, irrational belief systems construct the State’s technological apparatuses as operating benevolently. Yet, these technological systems are strictly utilized for increased control: Kafka’s bureaucratic machine (seen in Figure Six) and Foucault’s panopticon (seen in Figure Seven) serve as examples. Must we thank our oppressors for not piercing our skin when they have conditioned us to lacerate our own organs? We must deeply appreciate Kafka’s literary-machine (more than the prisoners and their cuts); not because Kafka serves to fabricate another system of desire, but because he frees desire from the trapping of power.

**Note: Michel Foucault utilizes Jeremy Bentham’s ideal prison as a metaphor for the panoptic gaze that the State constructs itself in the minds of its subjects. With a watchtower having the ability to look into every prison cell, prisoners are conditioned into following orders under the guise of the potentiality that they are being watched. Thusly, individuals police themselves and others as they are disciplined to do so.

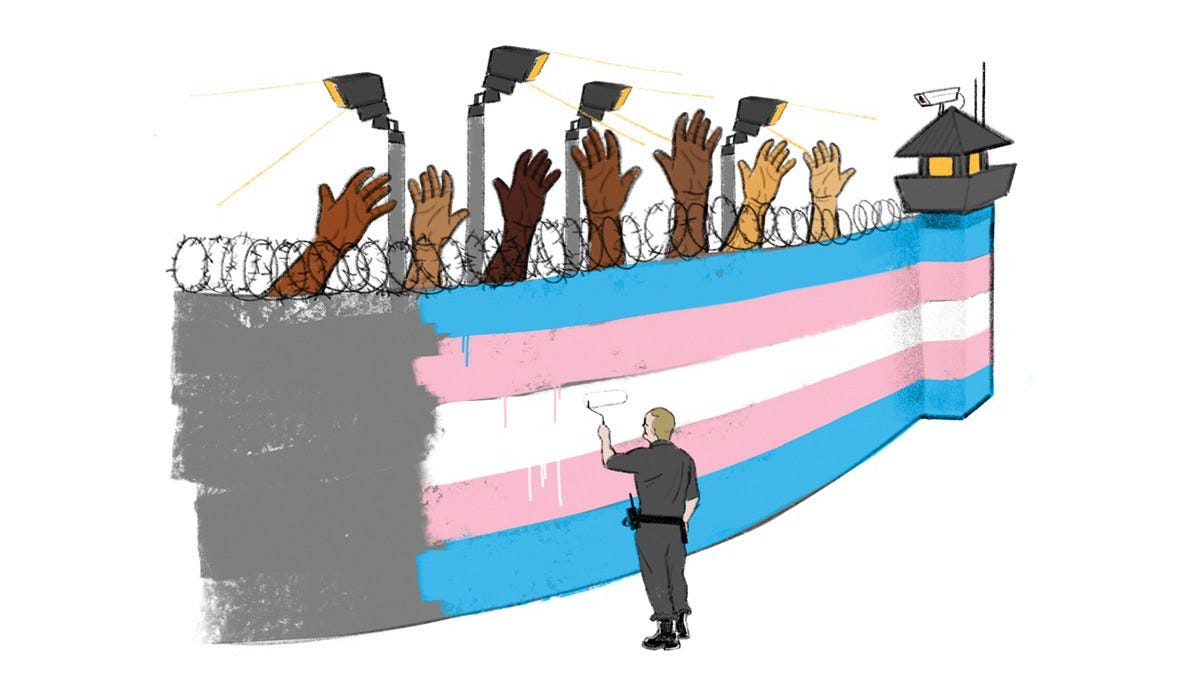

When discussing humaneness, in terms of power, one must understand that, through various humanistic tropes, the State exercises power in relation to specific bodies. Angela Davis is evidently clear in her explication that those who are “brown and black” occupy a “striking similarity to the condition of the prisoner” (1972). However, this analysis does not preclude non-Brown and non-Black individuals failing to occupy the positionality of the prisoner — policing tactics occur for all bodies embedded within a State, but the extent to which power is weaponized drastically varies in degrees of intensity depending upon the bodies at work.

We must cite a prominent afropessimistic framework here: the prison system of slavery transitioned into the prison system of Jim Crowe which transitioned into the prison system of the prison system. Without making an ontological statement on the condition of Blackness (as an afropessimist would), we must draw from Davis highlighting the disproportionate exercise of power that is inculcated upon the organs of certain populations: “violence is the man re-creating himself” (Fanon, No Date).

Obviously, an analysis of the prison must not be divorced from the structural conditions of someone deemed prisoner by the State. Davis isolates George Jackson’s description of life in Soledad Prison: “This place destroys the logical processes of the mind. A man’s thoughts become completely disorganized (…) He’s fallen as far as he can get into the social trap” (1972). In this manner, one must not view the prison system as anything other than a body; surely, individuals’ bodies occupy respective positions in prisons (guards, wardens, janitors, prisoners, etc.), but the prison is more than the sum of its parts. As prisons have set organs with strict markers of power present, the guards occupy the position of a prison’s intestines, the wardens occupy the position of a prison’s brain, the janitors occupy a prison’s digestive system, and the prisoners occupy a prison’s heart. Although everyone in this institution is systematized, one must not assume that all organs are created equal: the heart is the hardest working organ in the body.

A series of questions arise as we are stitched within various bodies and sewed into fixed positions: Can this system operate humanely? And, if it cannot, can one pick the locks on the prison doors to escape? To answer the first question, many have argued that the potentiality of liberal society utilizing progress to liberate its people is possible. Even Davis admits that “the wealth and the technology around us tells us that a free, humane, harmonious society lies very near” (1972). However, Davis is not optimistic in political reformism: “[humane society] is so far away because someone is holding the keys and that someone [refuses] to open the gates to freedom” (1972). Is it not evident that that ‘someone’ refusing to liberate the people is liberal society itself? Finding humaneness within a society predicated off the conditioning of bodies is a gross valorization of the State and seeks to minimize the effects of State power. The panoptic gaze never disappears with reform; as Professor Kammas, a former professor of mine, once stated: “Make the Penal Colony Great Again!”

For as long as the subject is constructed, escape remains an impossibility. For Foucault, the analysis ends here. He does not seek to provide an answer or solution to evading the State apparatus as he is only analyzing power relations; however, he criticizes particular theorists in the process. Of course, Freud and his predecessors, such as Jacques Lacan, disagree with much of Fouault’s analysis as they rely on a system of representations and the misplacement of desire; technologists argue that “psychoanalytic thinking could make for the betterment of society because you can change the way the mind functions” (The Century of Self. Dir. Adam Curtis. 2002.). However, if society positions desire in relation to lack, the subject’s construction remains inevitable as desire policies itself under a blanket of signifiers. Instead, desire must be understood in relation to abundance whereby conceptualizations of the self are artificial as bodies are in a constant state of flux; the State, with its absolutist perception, must corporealize itself by maintaining a strict sense of self. As Foucault is purely descriptive, rather than prescriptive (on the question of deconstructing the self), it is essential to examine the synthetization of Foucault’s power coupled with Deleuze and Guattari’s desire: Foucault writes in the preface to Anti-Oedipus, “Something essential is taking place (…) the tracking down of all varieties of fascism, from the enormous ones (…) to the petty ones that constitute the tyrannical bitterness of our everyday lives” (Anti-Oedipus, Preface, p. XIV).

Would it be a fallacious to assume that Foucault, Kafka, Davis, Deleuze and Guattari, and other writers have the capability to teach one how to amputate the watchtower within themselves? Foucault himself states that surveillance “is inscribed at the heart of the practice of teaching: (176). Understandably so, skepticism is a logical result of philosophies that stress escaping prisons as the notion of escape may be embedded within other systems of power. However, the status quo stresses the processual degradation of the body; it is evident that multifaceted policing tactics (whether it be through interpretive practices or legislative action) operationalize as tools of control.

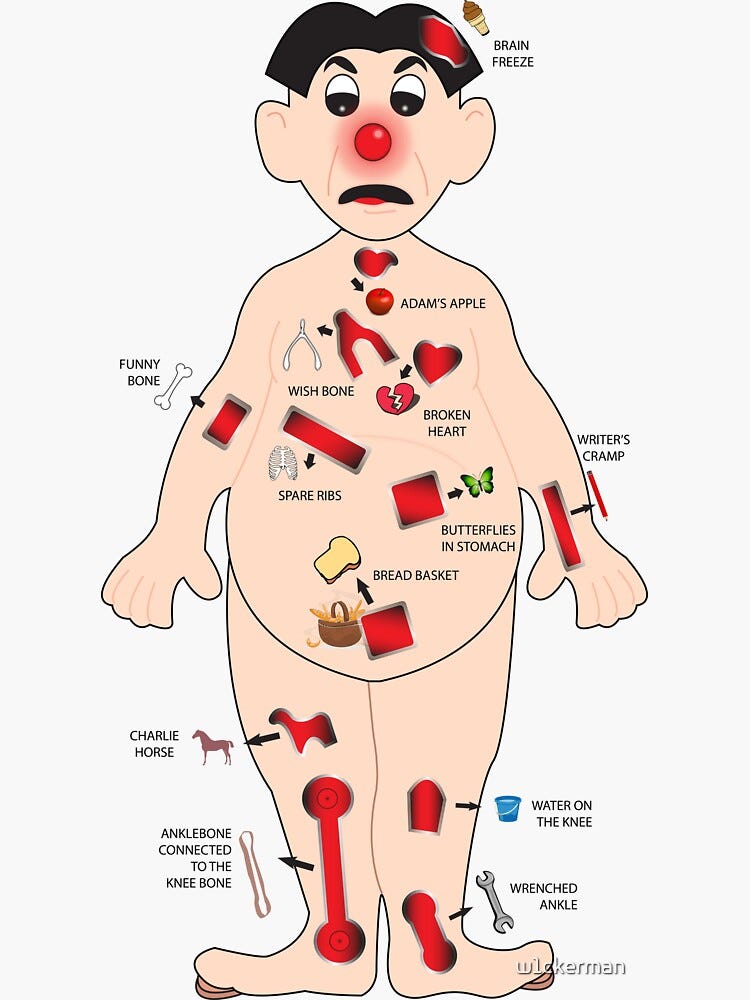

As judges wear the face of philosophy to guide their interpretations of law (i.e., originalism, textualism, interpretivism, aspirationalism, etc.), the answer is not regarding a pseudo-philosophy to identify with, but rather how one chooses to disorganize their organs. The necessity to rid oneself of one’s self remains prevalent in crafting social relations that are unique to the unfabricated forms of human nature. This requires a necessary precision (such as the precision found in the removal of organs in the game of Operation).

And so, take the dunce cap that has been crafted and invert its sign. One’s desire for power ought to be neutralized to the point where power is not present in one’s discourse and one’s material actions. None of this is to assume that instruments of governmentality will no longer view subjects as dividual data points; however, the goal is not the macropolitical, but rather, a micropolitical revolution. When one views the fascist inside themselves controlling their thoughts, actions, and speech, the desire to rid oneself of fascistic tendencies becomes increasingly apparent. As a result, you may be liberated. You may be disciplined. You may be punished. But no need to fear — you’re already disciplined and punished, so what is there to lose?

— —

Citations:

- Foucault, Michel. (1975). Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Second Vintage Books Edition. Vintage Books.

- Darabont, Frank, director. The Shawshank Redemption. Warner Bros., 1994.

- Lawrence v. Texas. Supreme Court of the United States, 2003.

- Webster v. Reproductive Health Services. Supreme Court of the United States, 1989.

- Planned Parenthood v. Casey. Supreme Court of the United States, 1992.

- Dworkin, Ronald. (No date). “Moral principle is the foundation of law.”

- Deleuze, Gilles, & Guattari, Félix. (1972). Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. University of Minnesota Press.

- Kafka, Franz. In the Penal Colony. Translated by Ian Johnson, Malaspina University, 1919.

- Davis, A. (Speaker). (1972, June 9). Speech delivered at the Embassy Auditorium.

- Fanon, F. (No date). “Violence is the man re-creating himself.”

- Curtis, A. (Writer & Director). (2002). The Century of the Self [Documentary]. BBC Four.

Leave a Reply