Realism, Liberalism, Cosmopolitanism, and more

International relations is an expansive field dedicated to the examination of interactions between various states. These interactions encompass economic, military, social, and cultural aspects, among others, all of which warrant thorough analysis. Yet, for comprehensive understanding of state behavior, we must look no further than the myriad of theories offered by renowned thinkers in this field. Critical theory in international relations delves into the descriptive nature of state behavior, providing insights into their operational dynamics.

This blog post seeks to explain the similarities and differences between Realism, Liberalism, Marxism, Constructivism, and other theories.

Realism

The image presented in Figure Two is derived from the 16th-century philosopher Thomas Hobbes’s book, The Leviathan. Although Hobbes does not explicitly discuss the nature of international relations, he is acknowledged as the foundational thinker who laid the ground work for what is now recognized as realist thinking. Hobbes believed that in the state of nature, humans are inherently self-interested and seek to maximize their individual needs. Because of this, he argued for the necessity of a central authority to impose order in the midst of a chaotic and anarchical state of nature — your body is the state’s property. (A better explanation of Hobbes can be found in a previous blog post of mine)

In any case, the principles of realist thinking are expanded to the international system through Hans Morgenthau’s influential work Politics Among Nations, published in 1948. This work argues that states are driven by a rational interest in pursuing power.

Therefore, let us define the concept of realism: a school of thought within international relations theory asserting that states, within an anarchical global system lacking a central authority, act in a self-interested fashion in their pursuit of power.

John Mearshiemer, an American political scientist recognized for his contributions to realism, states in his 2001 book, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics that:

“The structure of the international system forces states which seek only to be secure nonetheless to act aggressively toward each other.”

He isolates five pillars of realism:

- First, “the international system is anarchic.”

- Second, states “inherently possess some offensive military capability.”

- Third, states “can never be certain about other states’ intentions.”

- Fourth, “survival is the primary goal of great powers.”

- Fifth, states are “rational actors.”

By identifying the core tenets of realism, we are reminded of Niccolo Machiavelli’s The Prince, published in 1542. In The Prince, Machiavelli details the ruthless measures a prince must adopt in order to uphold and consolidate power.

At any rate, realism perceives states as rational actors driven by the pursuit of power, aiming to maximize interests. However, this view of international relations carries a pessimistic tone, allowing room for countries to assert dominance over others. An illustration of theory’s impact in shaping international relations is evident in the realist theories presented by George Kennan, an American diplomat and historian largely responsible for the Vietnam War. Kennan formulated the renowned theory of containment, suggesting that communism could be curtailed if confined within specific borders. This theory justified the invasion of Vietnam, resulting in the deployment of American troops under the guide of ‘containing communism,’ leading to the tragic loss of over a million lives, including numerous innocent civilians.

While realism encompasses a wide conceptualization and rationale for state behavior, some scholars have identified three specific areas within realism (so far). These areas all relate to the fundamental tenets of realism, but diverge in their perspectives on how realism is operationalized.

Offensive Realism:

Offensive realism contends that the pursuit of power manifests through offensive actions. Offensive realism contends that because the international system is anarchical, this leads to Instances such as the United States’ invasion of Vietnam or China’s expansion into the South China Sea exemplify states engaging in offensive behavior and actively pursuing aggression to uphold and enhance their power. (Offensive realism is closely associated with John Mearshiemer).

Defensive Realism:

Defensive realism contends that states are primarily driven by the desire to maintain current security levels rather than actively pursuing dominance. An example of this perspective can be observed in the behavior of isolationist countries such as North Korea. North Korea has publicly declared its possession of nuclear weapons, yet they are not actively seeking dominance in an offensive fashion.

Neorealism:

Neorealism, also known as structural realism, is closely associated with Kenneth Waltz and his work titled Theory of International Politics, published in 1979. This theory argues that states are selfish due to the structure of the international system. Unlike realism, it is not making a claim that states are naturally aggressive, but the system is what causes the aggression.

Liberalism

In contrast to realism, liberalism offers a far less pessimistic view of international relations. Liberalism is a school of thought that highlights the importance of the individual rights of states, the propagation of democracy, and global institutions (in shaping state behavior).

Contrary to viewing war or conflict as unavoidable, the liberal perspective posits that the establishment of positive relationships among states and global instiutitions holds the potential to mitigate sources of conflict. Liberals do not inherently assert that the international system lacks chaos; instead, they contend that this chaos can be navigated and overcome through the formation of institutions — entities that foster increased cooperation among states.

A foundational text for this liberalist perspective is 17th-century philosopher John Locke’s Second Treatise of Government, published in 1689.

In this text, Locke employs religious imagery to assert that the state of nature is not inherently anarchical, devoid of rules, but rather governed by a natural moral law ordained by God. Drawing on his Judeo-Christian background, Locke expands upon the story of Adam and Eve as an illustrative example of individual property rights.

In the initial chapters of Genesis, Adam and Eve exert physical labor to procure a fruit from the tree of knowledge of good and evil, despite God’s explicit prohibition. This action makes the picking of the fruit their choice, and by default, their property. Consequently, in the state of nature, asserting ownership over a piece of land, an object, or any other possession is akin to claiming it as one’s property. This principle extends to the body itself — your body is your property — diverging from Hobbes’ assertion that your body is the state’s property or Rousseau’s argument that your body is the collective’s property.

Therefore, from a Lockean perspective, the state exists not just to protect one’s life, but to protect one’s property. And, if we examine this from an international relations perspective, it becomes apparent that nations aspire to establish reciprocal relationships that enable them to preserve their autonomy, protecting their ‘life, liberty, and property.’

Another philosopher to examine, one who specifically focused on international relationsm, is Immanuel Kant. His book titled Perpetual Peace: A Philosophical Sketch, published in 1795, holds foundational importance in grasping a key aspect of liberalism: the democratic peace theory. Kant argued that representative democracies are less likely to go to war with one another. This assertion is grounded in the idea that countries fostering democracies are more likely to uphold democratic ideals, such as the protection of property.

Kant also introduced the concept of ‘cosmopolitan law’ (distinct from cosmopolitanism in international relations theory), emphasizing the importance of a shared global legal framework between states. By establishing shared legal frameworks that properly govern state behavior, the international system moves beyond the semblance of anarchy. (Some of Kant’s works reflect both liberalism and cosmopolitanism).

Liberalism can be characterized by three pillars:

- First, anarchy within the international system can be overcome through the creation and propagation of institutions (NATO, WTO, EU, etc.)

- Second, states that are representative democracies are less likely to go to war and engage in conflicts with other states.

- Third, states are naturally cooperative through mechanisms like treaties, foreign aid, humanitarian efforts, etc.

The presence of liberal institutions like that of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, the World Trade Organization, the Bretton Woods Institutions (IMF, World Bank, etc.), the World Health Organization, and others, prove that states are willing to cooperate with one another in order to mitigate conflict between states.

**Contemporary liberalists within international relations worth mentioning are: Daniel Deudney and John Ikenberry. They wrote Democratic Internationalism: An American Grand Strategy for a Post-exceptionalist Era in 2012, emphasizing the importance of reforming the international system.

While liberalism encompasses a wide conceptualization and rationale for state behavior, some scholars have identified three specific areas within liberalism (so far). These areas all relate to the fundamental tenets of liberalism, but diverge in their perspectives on how liberalism is operationalized.

Neoliberal Institutionalism: Within existing literature, the distinction between liberalism and neoliberal institutionalism is not sharply defined. Neoliberal institutionalism places a particular emphasis on the role of instutions facilitating and regulating cooperation among states. It delves into the examination of how institutions contribute to the create of stable relationships between countries, especially in the context of international trade and economic markets, while simultaneously giving states the ability to be strategic in their pursuit of power. Notice here, however, that the pursuit of power is not innately violent.

*Liberal Internationalism: This is synonymous with liberalism extended into the international system. To avoid confusion, scholars have coined “liberal internationalism” to be that of liberalism on the scale of aggregates of people rather than a single individual and a state.

Cosmopolitanism

Cosmopolitanism refers to the belief in a single, unified, global community that shares common moral and ethical goals. Cosmopolitanism emphasizes the concept of global citizenship whereby individuals have an obligation to concern themselves with what happens beyond their national borders.

This idea is closely linked to Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who writes after Locke. In his book The Social Contract published in 1762, Rousseau criticizes the kind of Lockean view of property rights. If Locke were correct in stating that the state’s only role is to protect life, liberty, and property, then issues like homelessness would be acceptable as long as homeless individuals retain their rights. However, Rousseau criticized this individualistic approach — he argued that instead of focusing solely on the individual, the emphasis should be on the community. Rousseau believed that humans are born inherently good but are corrupted by greed.

Cosmopolitanism applies Rousseau’s framework on a global scale, suggesting that nations, like individuals, are corrupted by greed but should ultimately share a common interest in uniting humanity. To be clear, advocates of cosmopolitanism do not believe the world is perfect, but they argue that countries should take ethical actions to create a unified global community. In essence, countries should approach conflicts abroad as we do those at home, recognizing that all humans share a common humanity.

A few thinkers of this tradition are: Kant (not all of his works), Nussbaum, and Appiah.

Marxism

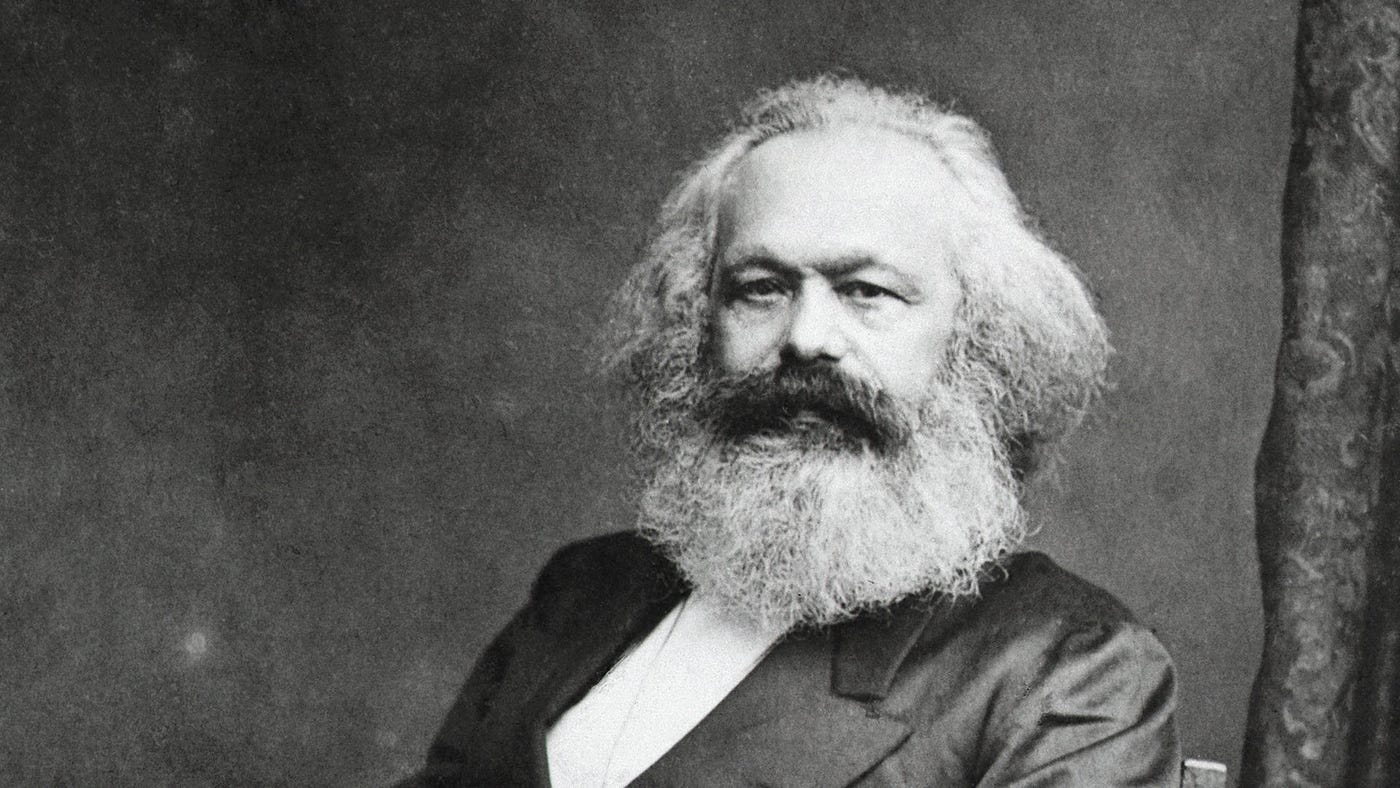

Unlike realism and liberalism which emphasize the conflict/cooperation divide, a Marxist conceptualization of international relations posits a new paradigm to view the relationship between states. Karl Marx, philosopher, economist, historian, and political theorist, asserts that capitalism as a socioeconomic system is transnational, structuring the behavior of states.

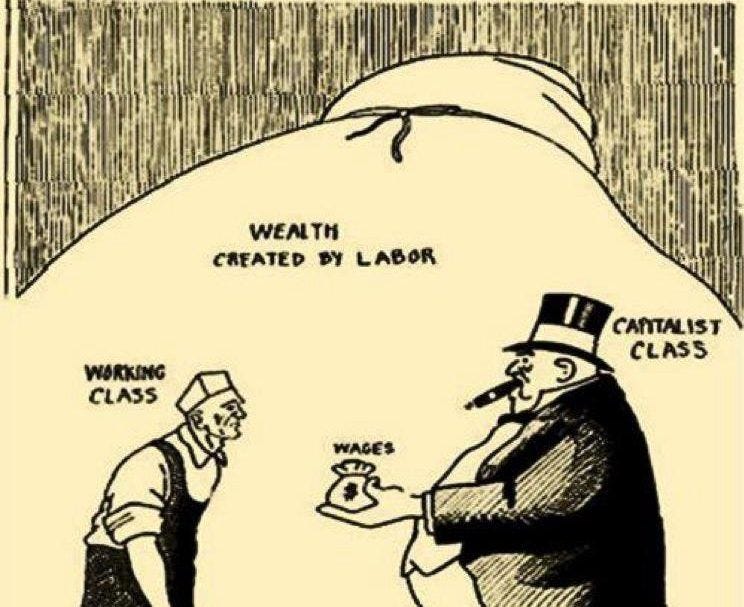

Without delving extensively into the intricacies of Marxist thought, it is essential to note that the generation of surplus under capitalism necessitates individuals to engage in more labor than is needed to survive. In other words, people work beyond what is necessary for mere survival to produce surplus for the bourgeoisie. According to Marx, individuals do not inherently desire to work excessively, rather, they are compelled to do so within a capitalist society. It is within this context that Marx raises questions about the necessity of capitalism for humanity.

Marx contends that the existence of the state is predicated and contingent upon class relations. For instance, if someone resorts to theft due to hunger, it is a consequence of an unjust distribution of resources where some hoard while others lack. Consequently, to curb and penalize such actions, the establishment of a state becomes imperative. Thus, under capitalism, a state is deemed necessary because individuals are constrained within an economic system where their worth is measured by their labor.

Marx explicitly asserts that: “labor is external to the worker, i.e., it does not belong to his essential being” (Marx and Engels Reader, 74). Labor is imposed upon humans in a manner that creates problems because it is not in human nature to steal; rather, individuals becomes corrupted due to an uneven distribution of resources and the desire to accumulate as many resources as possible.

Expanding the scope of capitalism to the scale of states, state behavior becomes apparent as states are aggregates of individuals — and these individuals are situated within a capitalist society. Consequently, according to Marx, conflicts among states and manifestations of violence, such as imperialism and colonialism, are products of states striving to flourish within a capitalist system. The accumulation of resources becomes a means to secure state power within the framework of capitalist international relations.

Therefore, a Marxist approach to international relations is not a question of the innate behavior of states, but rather, how states have become corrupted by class.

Constructivism

To put simply, constructivism conceptualizes international relations as a question of social construction. Constructivism focuses on the notions of norms, ideas, and beliefs shaping international relations — all while acknowledging that these social constructions are subject to change and in a constant state of flux.

Constructivists criticize endeavors that attempt to comprehend the international realm conclusively — that is, constructivists highlight the impossibility of fully perceiving international relations in a static manner. While constructivists recognize the existence of conflicts and cooperation between states, they argue that these dynamics are the result of various social relations that cannot be reduced to singular explanations.

- *Constructivist scholars include Alexander Wendt, Martha Finnemore, and Nicholas Onuf.

Other Theories

Though Realism, Liberalism, Cosmopolitanism, Marxism, and Constructivism are the most prominent theories in international relations literature, there are other theories that are extremely important. Here, I will provide a short definition of various theories.

Feminism: The belief that international relations ought to be examined from the standpoint of power dynamics in relation to sex and gender. This examination seeks to understand the impact of gender roles and patriarchy on the behavior of states. (See: Tickner, Enloe, Peterson, Sjoberg)

Securitization Studies: The belief that international relations operates within the framework of “securitization.” Securitization, developed by the Copenhagan School, concerns the behavior of states when confronted with a (potential) threat to their power. States’ reactions to threats involve taking extraordinary measures, thereby warranting exceptional actions (such as the United States invading Vietnam). Studies on securitization focus on the significance of language and rhetoric, particularly in the communication of threats, shaping the dynamics of international politics. (See: Barry Buzan and Ole Wæver)

Conclusion

While this blog post has dived into some of the essential orthodox — and non-orthodox — approaches to international relations, it is important to acknowledge the existence and plethora of additional perspectives beyond those discussed here. Nevertheless, the theories explored here provide valuable insight into the complicated world of international relations. Through the engagement of nuanced theories, we are better equipped to deal with analysis of international politics and relations.

Leave a Reply