Revisiting and revising an essay of mine that showcases the brilliance of Foucault’s History of Sexuality — Vol. 1

**Citation Note: Full citation provided at the end of this post

History of Sexuality — Vol. 1

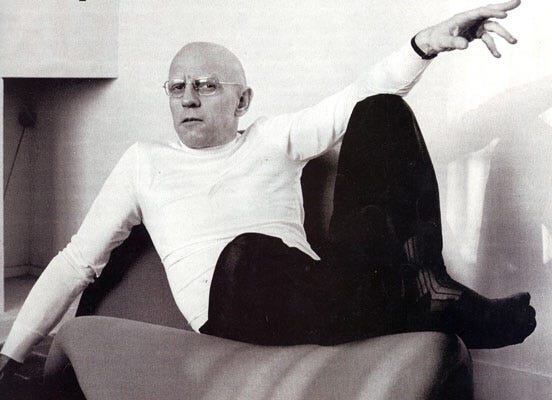

At any rate, you are sexed (and have been). Michel Foucault’s History of Sexuality knew this fact from the very beginning. It is not so much a discourse surrounding inquiries of what is sexed as these questions are largely unimportant; the better question that ought to be asked is: what isn’t sexed?

If an educator were to roll the pages of this essay into the geometric shape of a cylinder — perhaps to punish a student — would the student not find the empty space of this tube-shaped figure to represent a hole in which the phallus must be inserted? Or is this phallocentric representation (along with representations tied to sexual drives writ large) just another discourse rooted in modernity? Sigmund Freud, openly theorizing sexual behavior, reinscribes his phallocentrism into a discourse centered on sex and sexuality. From the very beginning of Freud’s analysis, every act was deemed in relation to sexual drives; we were doomed from the very start. Yet, as Foucault writes:

Until Freud at least, the discourse on sex — the discourse of scholars and theoreticians — never ceased to hide the thing it was speaking about. (53)

Therefore, what is sex? And, in this case, what was sex before Freud? Evidently, sex and sexuality are rooted in discourse, and psychoanalytic interventions appear to impose hegemonic, static representations into the discourse that constitutes sex and sexuality: “… The Freudian endeavor … to surround desire with all the trappings of the old order of power” (150).

Yet, if sex and sexuality are rooted in discourse — with discourse seemingly guided by representations — then a better, more substantive question must be posed: can discourse as sex or sex as discourse ever evade the State apparatus? As biopolitical regimes, in their discursive functionalisms, universalize what entails normative bodily functions and behaviors, the State operates fluidly in its legalistic definitions of what constitutes correct usages of the body. Foucault, in all his brilliance, posits a history of sexuality that interrogates the discourse on sex and sexuality, along with the organization of bodies according to lines of sexual codes (a chronological anatomy). For Foucault, this discourse is ever-changing.

Thusly, we have concluded that sex and sexuality operationalize through discourse. However, Foucault writes:

“We must not refer to a history of sexuality to the agency of sex; but rather show how ‘sex’ is historically subordinate to sexuality.” (157)

In this context, Foucault’s examination is not specifically on individual sexual acts; rather, he directs attention to the broader sociopolitical realm concerning the concept of sexuality. His argument does not propose a strict sequence where one must first possess a defined sexuality before engaging in sexual activities; instead, he contends that sexuality encompasses more than mere physical acts, emphasizing the intricate dimensions that constitute sexuality.

Foucault writes that the discourse of sex and sexuality is rooted in a power that is both generative and productive: in the 20th Century, there marked a shift, an evolution of a sexual kind, “a moment when the mechanisms of repression were seen as beginning to loosen their grip” (115). Foucault’s gripe with the repressive hypothesis (a theory which postulated that sexuality was hidden prior to modern times) is that of its contrary; sexuality was never repressed, but is instead, always topical, and readily present in various formations of discourse:

… One passed from insistent sexual taboos to a relative tolerance with regard to prenuptial or extramarital relations; the disqualification of ‘perverts’ diminished, their condemnation by the law was in part eliminated; a good many of the taboos that weighted on children were lifted. (115)

Therefore, subjectivity is produced through a set of social relations that are constituted within a network, with power being exercised across this decentralized plane. In other words, subjectivity is produced through a set of power relations. In The Subject and Power, Foucault writes that power and the exercise of it is “a set of actions upon other actions” which crafts particularized dichotomies that reinscribe hierarchies of exclusion.

The exercise of power not only shapes subjectivities, but it produces hierarchies that determine which subjectivities (in this case, sexualities) are legitimate. Hierarchies pertaining to the exclusion of bodies presupposes the fact that the State’s goal was always one of classification: an organization of subjectivities. Foucault writes: “At the heart of this political problem of population was sex … The sexual conduct of the population was taken both as an object of analysis and as a target of intervention … There was formed a whole grid of observations regarding sex” (25–26).

There are a plethora of examples whereby individuals occupying certain subjectivities become excluded after a particularized classification. No doubt, the homosexual was excluded after their classification of being mentally ill, occupying an unproductive sexuality: “the homosexual was now a species” (43). Discourse implicates one’s biophysical body as the the homosexual is put into a site of interrogation; an object of study: “We must not forget that the psychological, psychiatric, medical category of homosexuality was constituted from the moment it was characterized” (43).

Evidently, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) loosened their grip on sodomy in 1973 by removing the diagnosis of homosexuality from their language. Though this appears to be a progressive move towards equality, Foucault is questioning the underlying assumption that homosexuality must be defined legalistically by the State apparatus along with the presumption that homosexuality must be legitimized by said apparatus. For Foucault, the move by the APA to redefine homosexuality only indicates a shift in the sex and sexuality as a discourse. Foucault states:

“Sexuality must not be thought of as a kind of natural given … It is the name that can be given to a historical construct.” (105)

Properly so, sexuality (as an embodied power relation) promulgates sex to an inferior status as sex must be expressed in a typified way that depends upon a network of power relations that constitute it. There are many examples of this conundrum whereby gestures (and acts) are deemed homosexual: a man crosses his legs, a boy puts his hand down in a fluid motion, a husband states that he has HIV. As such, Foucault declares that “[sexuality] is what gave rise to the notion of sex, as a speculative element necessary to its operation” (157). Foucault recognizes the very real nature of sexuality being produced; and through the production of sexuality, the classification and categorization of sexual acts are produced as well.

The speculation that Foucault discusses, (which one could call the ‘panoptic gaze’), attempts to organize bodies in an artificial manner whereby people function as codified subjects of a State apparatus. But we must ask: Who determines this ideal performance of sexuality? Rather facetiously, Foucault writes: “we shall leave it to psychoanalysts to speculate whether [Don Juan] was homosexual, narcissistic, or impotent” (40). Psychoanalysis — the arbitrary structuralization and fashioning of one’s desires — erroneously prescribes power as a top-down modality whereby a despotic center inscribes everything into discourse. The psychoanalyst inculcates the very binaries that sustain discursive representations: sane/insane, hetero-/homo-, cured/diseased. Yet, the supposed ‘lifting of repression’ by the APA, for example, does not change the fact that power operates as a decentralized network; the exercise of power where individuals’ sexualities are policed occurs in all domains of life.

Biopower requires a discipline of the body and a regulation of the population — with sex fitting neatly at the center of this intersection. Unfortunately, many individuals — licensed or not — take their DSM books and regulate the performance of sexuality in their day-to-day lives. (Even silence is a discourse as Ronald Reagan stuck his head in the sand during the HIV/AIDS crisis).

All sexualities, deemed legitimate or not, are discursively represented by the State apparatus. We are well aware that deviation from the established (sexual) norms may lead one to a tortuous, painful death. However, the intimate relationality the biophysical body has with pleasure allows Foucault to offer an optimistic political praxis. Points of resistance against exercises of power exist, however, Foucault finds resistance as being embedded within their own exercises of power: power is always present. If one challenges the dominant sexual code (possibly with handkerchief codes or sexual contracts presented as essays), a liberatory feeling may arise (and one may not be suffer a tortuous, painful death); however, one must not forget that these resistance strategies are just another discourse on sexuality.

Thus, blog posts, too, are sexed.

— —

Citation:

- Foucault, Michel. The History of Sexuality: Volume 1. New York: Vintage Books. Translated by Robert Hurley. 1976.

Leave a Reply