Introducing a Deleuzoguattarian philosophy in the classroom through a series of becomings

“Is life not a thousand times too short for us to bore ourselves?”

Friedrich Nietzsche (1886)

This Nietzsche quote gets to the bottom of what I have been feeling lately. Over the past week, I have been dealing with the concept of boredom in the classroom. Students rubbing their eyes and slouching over their computers (with their eyes slowly closing) is commonplace. Every teacher has experienced this. When analyzing social relations, we must be cognizant of the fact that the ability to listen to one another relies on the ability to be engaged.

To understand boredom in the classroom, we might want to start with one of the most boring days: syllabus day. In Anna Smol’s blog Think like a Professor! — or, how to defeat syllabus boredom, I felt a connection to Smol’s explanation of what the syllabus looks like from the students’ perspective. Smol writes:

It’s the first day of class, and we all know the drill. The course outlines, with requirements, expectations, and policies detailing how your course will be run, must be handed out. You need to get your students to read what must look to them like the fine print of a long contract — one of several outlines they’ll be collecting in the first couple of days. Especially for first-year students just out of high school, course outlines may present a confusing array of do’s and don’ts: all assignments must use APA, or was that MLA? No late papers will be accepted, but sometimes late papers will have points deducted. You must have a note for absences, but some profs don’t take attendance. You have to write all the assignments to pass, but didn’t someone say that you could do extra assignments for additional credit?

Essentially, the syllabus appears as a contract, riddled with fine print that students must read over while being told what is required of them. Quite boring.

Yet, in a Deleuzian manner, Smol reframes the syllabus to be a modality for students to explore in what Smol calls “Think like a Professor!” Smol explains:

[The students’] task is to imagine that they are the professor of our course and have written the course outline, including all of its policies, expectations, and requirements, and that they will now be faced with various situations, all based on actual events, in which they will have to apply the rules of the course.

Proactive approaches to boredom is necessary for the teacher to combat that dreadful apathy in their classrooms. Boredom occurs for both teachers and students. This is not to assume that a teachers and students are engaging in problematic behavior by being bored as boredom is part of the human condition. Especially in the face of capitalist modernity, many teachers are working longer hours with an increasing number of students; no wonder people are feeling bored due to being overworked!

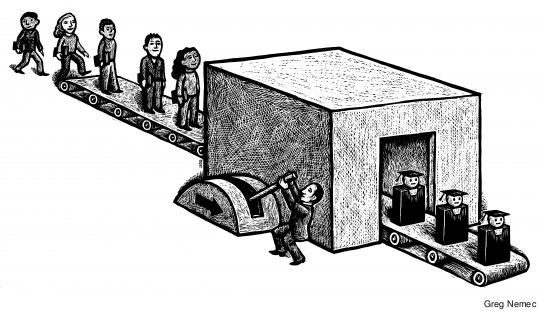

Olúfémi Táíwó, a philosophy professor in New York City, puts it best by proclaiming, “I am a teacher — not a jobs trainer.” Yet, we cannot discard the fact that teachers are deemed as ‘job trainers’. Regardless, many argue that there is little time to be bored with an ever-changing educational landscape. How can one be bored when they have so much to do? But we do find that boredom pervades all spaces — including educational ones.

As a K-12 educator, I have noticed that boredom is prevalent within all classrooms. However, boredom arises in different ways depending on the class that I’m teaching. For example, my elementary students constantly challenge me, but the curriculum is so simple that it isn’t very engaging (for me, at least). This is the opposite from my high school classes. The material is much more difficult, but boredom can still be found in teaching the same abstract concepts repeatedly. So … how do teachers combat boredom in the classroom? The answer lies in the incorporation of varying educational modalities to keep things in the classroom interesting.

For both the teacher and student, repetitious behavior is the perfect foundation for boredom to arise. Rather than utilizing the same curriculum and outline for every class, it is integral that teachers incorporate projects, discussions, and lectures into a wider array of potential. In a 9–5 culture where every aspect of one’s day is planned out, it is no surprise that the mantra of 21st century corporate America is: “I’m bored!”

As educational bloggers repeatedly cite Paulo Freire — a philosopher who has explicitly analyzed how the classroom operates like that of a training ground for corporatized work — educators must challenge this corporatization. With the teacher’s 9–5 embedded into the curriculum, it is obvious that there is a struggle in tackling the normative view of the classroom as a workplace. Critical theory blogger, Sahil Dudani, describes Freire’s opposition to the classroom as a job training ground by stating:

Freire believes that education is fundamentally an act of love because the factors essential for education are solidarity, equal footing and mutual respect.

I do not believe the question is solely about how to combat boredom, but also whether boredom is inevitable. I mean, teachers and students are people too; sometimes it would be nicer to scroll on social media aimlessly instead of telling a child to not say bad words. Yet, as teachers, we still find the project of teaching to be admirable and find there to be value in crafting intelligent individuals with the capacity to critically think (even if sometimes we’d rather be scrolling on social media).

At any rate, we must answer the question with a resounding yes. Boredom is inevitable as we are humans with the attention spans of goldfish. However, knowing that boredom comes and goes within the classroom, the teacher must craft a critical pedagogy that seeks to consistently challenge the notion of the 9–5 classroom. Although this is a difficult task that requires a level of precision not taught within normative educational spaces, deconstructing the classroom to combat boredom seems to be a worthwhile project. For example, Ulrika Bossér and Mats Lindahl’s 2017 study proved that certain practices, such as allowing students to occupy a position of authority in the classroom, deconstructs the teacher-student hierarchy. By deconstructing this hierarchy, students were found to be more engaged.

So, it begs the question: what methods can we employ to challenge boredom in the classroom?

Leave a Reply