Introducing a Deleuzoguattarian philosophy in the classroom through a series of becomings

Within educational spaces, every aspect of knowledge production must align with a centralized educational focal point, embodying a form of despotic importance. Responses, essays, and even blog entries must conform to specific criteria in shaping and presenting information. However, the question arises: who determines the correctness of these criteria?

While it is essential to scrutinize dominant structures, it is equally imperative to reject outright inaccuracies. Although a student may resist conformity by asserting that 2+2 does not equal 4, it becomes necessary to delineate and uphold a standard of correctness. This ensures that, despite challenging prevailing norms, students aren’t left with misconceptions as they transition into society.

To thoroughly examine the question of integrating presumed objective standards in the classroom, it is crucial to involve students in this discourse. By enabling students to interact with the curriculum more tangibly and in a more captivating manner, many education scholars have embraced the latest trend known as the flipped classroom.

Harvard provides a well-crafted definition that states:

A flipped classroom is structured around the idea that lecture or direct instruction is not the best use of class time. Instead students encounter information before class, freeing class time for activities that involve higher order thinking.

In the past week, I have embraced the process of flipping the classroom. Instead of delivering traditional lectures in class (and relying on last-minute engagement with the material), I assigned YouTube video lectures — ones that I created — for homework. This has allowed students more time during class to explore diverse approaches to the material. Through the process of flipping the classroom, I challenged my own understanding of the curriculum, and became willing to accept alternative perspectives to learning.

Intrigued by the idea of flipping the classroom and with the results it yielded, I continued researching the benefits of flipping the classroom. During my research, I stumbled upon the concept of flipping the teacher.

According to Panopto:

“Flipping the teacher” has become a catch-all term to refer to just about any means by which educators can have students lead the classroom.

Flipping the teacher pushes students not merely to learn a few facts about a subject, but to actually comprehend the lesson well enough to synthesize its details into a cohesive, coherent presentation.

We are all familiar with the traditional student presentations, exemplifying the concept of flipping the teacher. (Nevertheless, educators need to explore alternative methods through which flipped teaching manifests.)

All of this reminds me of a rhizomatic approach to learning. Schizoanalytic blogger, Christina Hendrix, explains the concept of the rhizome within education quite well:

We can’t ever know exactly where we are going to go in learning, and […] everyone’s learning experience will be different.

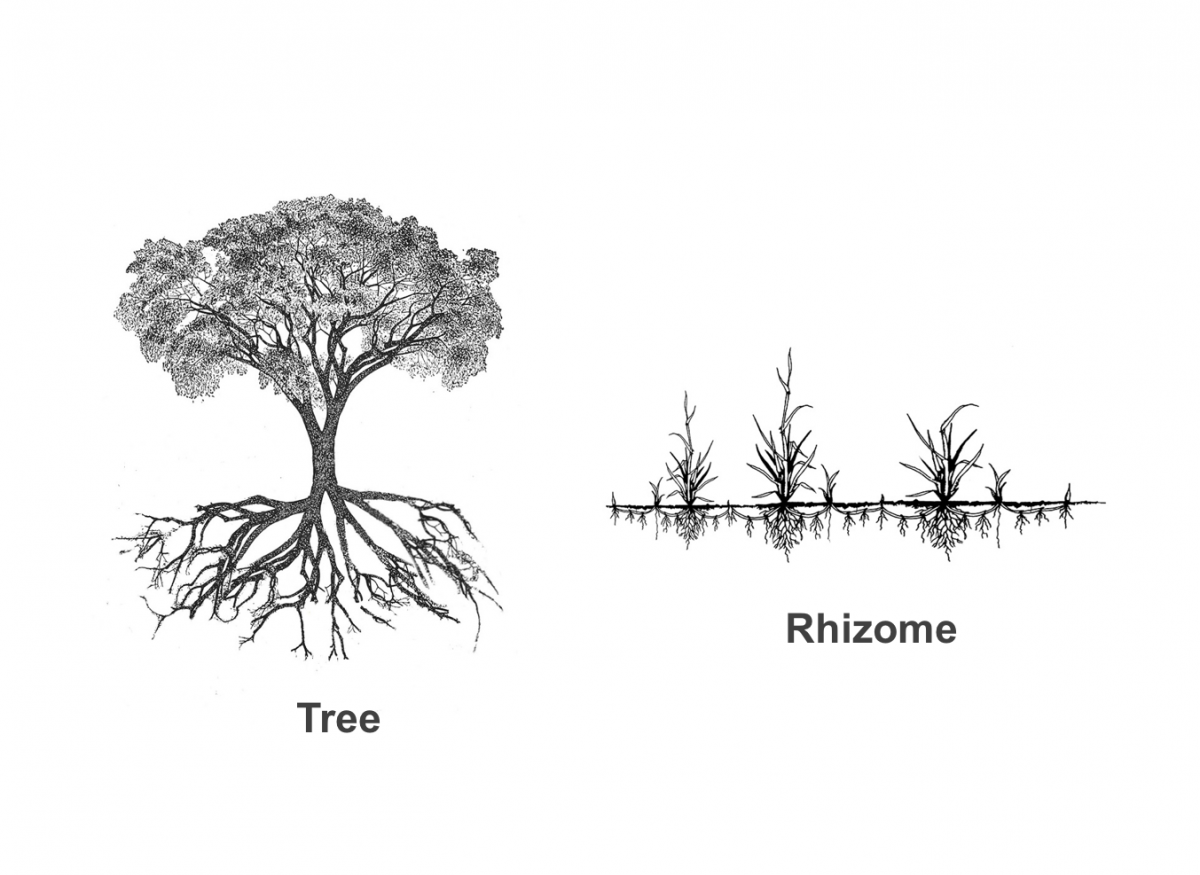

Deleuze and Guattari view the rhizome as a non-hierarchical, interconnected structure, contrasting it with an arborescent framework. Instead of conforming to a top-down model where knowledge production follows a uniform structure, the rhizome embraces the idea of venturing into the unknown, fostering exploration of diverse approaches to both learning and teaching. It embodies a dynamic and flexible network that contests traditional boundaries. (More of the rhizome will be discussed in a future blog post.)

Yet, the rhizome does not entail pure anarchy — progress must be made.

I worry that at times [teachers] might embrace the chaos and give the least amount of structure possible.

I agree; especially as some of my classes have approached a level of anarchy. In embracing rhizomatic education, I have discarded the notion that every imposition of thought is inherently negative. Why? Because the rhizome transcends binary distinctions, such as the simplistic categorization of good and bad. It is essential to impart correct answers to questions rooted in what we recognize as truth while fostering and enriching the creative approaches students employ to arrive at these truths.

Mandating a specific answer to a question is not inherently wrong or morally objectionable, but it requires precision. While mathematical equations have definitive answers within the constructed language of mathematics, arbitrary hierarchies still persist in math classes. For example, some renowned mathematicians faced criticisms for their proofs; while correct answers exist in mathematics, the pioneers who formulated these questions and discovered the solutions to these questions often diverged from normative thought.

At any rate, students enroll in various classes beyond mathematics, including English and other humanities courses that raise questions about correctness. Assessing a piece of art in a non-arbitrary manner poses a challenge. Teachers, tasked with assigning a rigid, often capricious aesthetic value for the sake of consumption and comparisons, need to approach students’ creativity with care. In my classes, writing styles exhibit significant variation. So, instead of adopting an absolutist grading approach for essays, papers, and speeches, I employ a relativist standard.

However, what is the rationale for this approach? How can I assess their understanding when each paper differs in terms of organization, structure, and content? This leads to the question of the fine line between creativity and intelligibility: at what point is an essay incoherent in its thought? None of this is to imply that unclear thought lacks value, but rather, if an essay is meant for another reader to read, then it should be comprehensible.

In any class, an educator’s transparency is crucial for fostering healthy communication between teachers and students. As educators responsible for assessing knowledge production, it is important to abandon convention thinking and empower students to discover more effective approaches to problem-solving, regardless of the subject.

So … is there a right and a wrong? Not really … well, kind of. We know that certain truths are necessary to conceptualize within the socius we occupy. But at the same time, we ought to inspire others to engage in creative, intellectual endeavors.

Leave a Reply